How to trash confidence in a COVID-19 vaccine: Brexit edition

By Stephan Lewandowsky, Stefanie Egidy, Ralph Hertwig, Ulrike Hahn | August 5, 2021

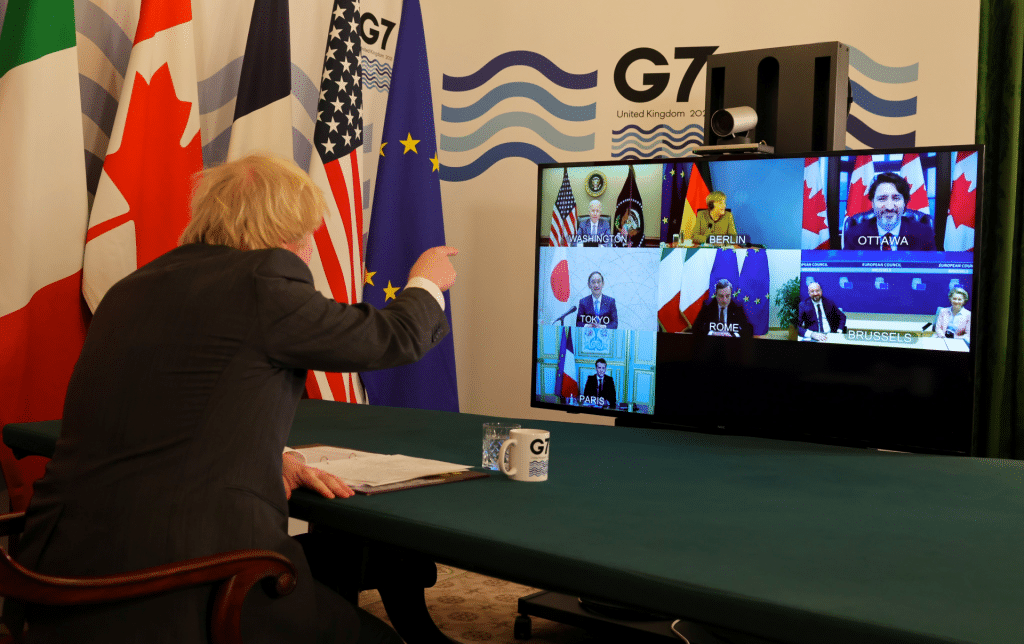

UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson meets virtually with other world leaders. The politics of the United Kingdom's acrimonious divorce from the European Union have helped to tank confidence in Oxford University and AstraZeneca's coronavirus vaccine. Credit: Boris Johnson's Twitter account.

UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson meets virtually with other world leaders. The politics of the United Kingdom's acrimonious divorce from the European Union have helped to tank confidence in Oxford University and AstraZeneca's coronavirus vaccine. Credit: Boris Johnson's Twitter account.

When AstraZeneca and Oxford University’s COVID-19 vaccine candidate passed its large-scale clinical trials in late November last year, the company was rightfully excited. It had an effective vaccine, 200 million projected doses to deliver in 2020 alone, and a product that didn’t need complicated ultra-cold storage protocols like its rivals. AstraZeneca had “a vaccine for the world,” an Oxford Vaccine Group official told Reuters. But the company hit bumps in the road almost immediately after announcing the trial results—for example, its claim that the vaccine could be 90 percent effective was compromised by a mistake in dosages during testing.

The rollout hasn’t gotten much smoother since.

Nowhere, arguably, is that more true than in Europe. Put simply, the company failed to deliver 90 million doses to EU countries during the first quarter of 2021, while still managing to supply the United Kingdom with more than 20 million doses. At the same time, European regulators were investigating safety concerns with the vaccine. Exasperated politicians like French President Emmanuel Macron were spreading misinformation, seemingly ready to believe the worst about the jab. The British press was parsing vaccine news through the lens of their country’s acrimonious divorce from Europe, Brexit. And AstraZeneca itself was dissembling about why it couldn’t deliver on its commitments to the continent, leading to a legal and rhetorical showdown with the European Union.

The result has been a fight between the United Kingdom, the European Union, and AstraZeneca that, in turn, has pummeled public confidence in the vaccine across Europe.

The EU fueled the UK’s quick vaccine rollout. By late April, half of the British population had received at least one shot of a COVID-19 vaccine, placing the country ahead of the United States and its neighbors in the European Union.

Two decisions made this possible. First, the United Kingdom granted emergency approval to the Pfizer/BioNTech and AstraZeneca vaccines in December 2020, several weeks before AstraZeneca had even applied for approval to the EU regulator, known as the European Medicines Agency, or EMA. Second, the United Kingdom decided to administer first doses of the two-shot regimes to as many people as possible, even if it meant delaying the second dose required for complete protection by 12 weeks—at least nine weeks more than recommended by the manufacturers. While the decision to further space the shots apart initially met with resistance from Pfizer/BioNTech, subsequent research confirmed that both vaccines induced strong antibody generation after a single dose, and that a greater delay between the two shots actually enhanced protection after the second dose of AstraZeneca was administered. (The new delta variant changes this picture. Evidence suggests that while two doses offer a high degree of protection, a single shot of the Pfizer/BioNTech or AstraZeneca vaccine leaves people vulnerable to infection.)

With their country so far ahead in the vaccine race, the British media understandably celebrated the country’s success. Coverage often took on a nationalistic tone. The rollout was framed as a British “victory” over the “failing” European Union. But the so-called victory was based on the slimmest of margins: While the United Kingdom was far ahead in the rollout of its first shot (50 percent versus 24 percent for the European Union) by late April, several EU member states (Germany, Netherlands, Italy, and France) were already catching up quickly, vaccinating at a faster per capita rate than the United States, which had been meeting ambitious targets early in its vaccination campaign. By August, several EU countries such as Denmark, Belgium, Spain, Portugal, and the Netherlands had surpassed the United Kingdom, and the European Union as a whole had overtaken the United States in terms of the share of the population fully vaccinated against COVID-19.

The British media’s frequently nationalistic reporting on the vaccine rollout masked the fact the country’s success relied in large part on EU-made doses: By the end of March, roughly two-thirds (21 million) of all shots administered in the United Kingdom were imported from the European Union. Without these doses, the United Kingdom would have been able to give one shot to at most 20 percent of its population, less than half the actual figure at the time. The European Union’s vaccine production capacity and more permissive export policies (relative to the United States and the United Kingdom) underwrote the United Kingdom’s successful rollout.

British media coverage largely ignored the European Union’s supporting role in their country’s vaccine rollout. When the European Union and AstraZeneca began arguing over delayed deliveries and their contract, British tabloids—famous for sensationalism—appeared to claim the vaccines were the United Kingdom’s to begin with—even though AstraZeneca had signed contracts with both the United Kingdom and the European Union. The British media published articles with headlines such as “NO, EU CAN’T HAVE OUR JABS” (Daily Mail) or “WAIT YOUR TURN! SELFISH EU WANTS OUR VACCINES” (Daily Express).

EXPRESS: WAIT YOUR TURN! Selfish EU wants our vaccines #TomorrowsPapersToday pic.twitter.com/NcUnLyJNej

— Neil Henderson (@hendopolis) January 27, 2021

And the UK media didn’t stop at applying the Brexit lens to contractual disputes. They initially also glossed over EU safety concerns with regard to the AstraZeneca vaccine, characterizing European regulators as overly cautious or even just upset over Brexit.

The regulators had begun investigating rare blood clotting incidents among AstraZeneca vaccine recipients in early March. When several European countries suspended the vaccine either entirely or restricted it to older people at less risk from blood clotting, one British commentator from The Telegraph, Philip Johnston, asked whether “the countries suspending the roll-out of the AstraZeneca vaccine against Covid [had] taken collective leave of their senses?” Another Telegraph commentator, Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, proclaimed that “the precautionary principle is literally killing Europe.”

A tabloid journalist from The Sun, Ben Hill, surmised that the suspension was the result of a “Brexit Sulk” while the Daily Mail’s Sam Blanchard claimed that the European Union “admitted” that the suspension was political. Conservative columnist Tony Parsons opined on Twitter that “The European Union would rather see their people die than the United Kingdom succeed. They have smeared the brilliant cheap efficient AstraZeneca vaccine—an act of medical stupidity and political insanity.”

Watching the dispute from afar, The Irish Times commented that “… everything seems somehow connected to the decision to leave…. British [government] ministers treat every question about the safety or effectiveness of the vaccine as a grievous insult to national honour.”

The British public also appeared to view the AstraZeneca controversy more in the context of Brexit than the public did in EU member states. A Google Trends analysis shows that search volume for the two terms “Brexit and AstraZeneca” was far lower (or indeed absent) in EU countries than in the United Kingdom.

This nationalistic public climate in the United Kingdom may have placed scientists and policy makers under considerable pressure and may have contributed to delaying official recognition of the AstraZeneca vaccine’s side effects by several weeks. British risk experts initially questioned the European suspensions—statistically a few people in a population are expected to suffer blood clots whether they’ve been vaccinated or not. But it soon became inescapable that these incidents of blood-clotting—also known as thrombotic events—were characterized by an extremely rare and unusual combination of symptoms that fingerprinted them as side effects of the vaccine. On April 7, UK regulators mirrored European regulators by accepting an independent recommendation that people younger than 30 should be offered an alternative to the AstraZeneca jab to reduce the risks of vaccination.

Neither the initial reports of side effects nor the regulator’s recommendations had much effect on the British public’s trust in the AstraZeneca vaccine. The only observable shift was that the share of people in surveys who thought the vaccine was “very safe” declined from 47 percent in mid-March to 41 percent by early April, with the percentage of respondents who said it was “somewhat safe” rising from 30 percent to 34 percent.

The public’s continued confidence in the AstraZeneca vaccine may have been an ironic consequence of the intense focus on Brexit: While the nationalistic slant of the British media led to much biased or outright false reporting of the AstraZeneca controversy, that same slant may have also preserved the British public’s trust in the vaccine at a time when things unfolded very differently on the continent.

Smoke, mirrors, and AstraZeneca’s competing contracts. The EU contracted AstraZeneca to deliver 120 million doses during the first quarter of 2021, but the plan stumbled almost immediately. In January, February, and March, AstraZeneca announced successive major reductions in supplies to EU countries. At the end of the first quarter, AstraZeneca had fulfilled only 25 percent of its contractual obligations to the European Union. If the company had met its obligations, the European Union would have obtained double the 88 million doses overall that it was able to procure from all suppliers by the end of March. This would have put the European Union in the vicinity of the United States, a leader in terms of per capita vaccine availability at the time.

While AstraZeneca continually reduced deliveries to the European Union, it fulfilled its competing obligations to the United Kingdom. The company offered various justifications for its selective breach of the EU contract, including that the European Union signed its contract three months after the United Kingdom, and that the UK contract was legally superior.

These reasons do not withstand scrutiny.

Both contracts are now at least partially in the public domain: The UK contract was signed on August 28, 2020, the day after the European Union’s went into force, challenging the chronology offered by AstraZeneca as reason for prioritizing the UK deliveries.

Moreover, the EU contract lists various production sites for “initial EU doses” as part of the supply chain, which, crucially, explicitly includes sites located in the United Kingdom.

Finally, both contracts contain a “best reasonable efforts” clause. AstraZeneca’s obligations to the European Union were not extinguished by a competing contract: If both contracts could not be fulfilled simultaneously, this simply means that AstraZeneca sold a limited supply of a life-saving commodity twice, and had to make a choice about which contract to comply with and which contract to breach.

There is, however, one critical difference between the two contracts: The UK deal includes harsh penalties for non-deliveries whereas the EU deal contains no penalties and waives any claim arising out of delivery delays.

The lack of teeth does not make the EU contract legally “inferior to the UK’s,” as the former British health secretary has claimed, however, the EU contract is less costly to breach than the UK counterpart.

The European Union filed a lawsuit in late April against AstraZeneca over its failure to deliver hundreds of millions of doses. In a preliminary judgment in June, a court in Belgium ruled that AstraZeneca committed a “serious breach” of its contract with the European Union and had “not made its best reasonable efforts to manufacture and deliver” the promised doses. The court also ordered AstraZeneca to deliver 50 million doses by late September or else pay a 500 million Euro fine, although that order fell short of EU demands.

Misinformation about the AstraZeneca vaccine. Compounding the fallout from the contractual disputes, some European media and politicians produced and published false or misleading information about the AstraZeneca vaccine itself, according to an investigative report in The BMJ medical journal. The German government’s vaccination committee in January recommended that only adults between the ages of 18 and 64 get the AstraZeneca vaccine, citing the lack of data for older participants in the company’s trials, according to the Robert Koch Institute. Unfortunately, the German newspaper Handelsblatt misreported the lack of data as a sign that the vaccine lacked effectiveness, claiming on January 25 that “representatives of the Federal Government fear a lower effectiveness of the vaccine—several sources naming a figure of only 8 percent.”

Although this claim was swiftly rebutted, including by the German Federal Ministry of Health, it was reiterated by French President Emmanuel Macron several days later. Politico reported that on the same day that European Regulators approved AstraZeneca for all adults, Macron told reporters: “We’re waiting for the EMA results, but today everything points to thinking it is quasi-ineffective on people older than 65, some say those 60 years or older.” It was not a shining endorsement of a vaccine from a president. And leaders can have a huge impact on vaccine confidence.

Some media outlets in the United Kingdom—even including the opinion sections of medical journals—interpreted Macron’s statement to be revenge for Brexit.

In the European Union, the misinformation from Handelsblatt and reiterated by Macron fell on fertile ground, coming as it did just days after AstraZeneca’s first announcement of reduced deliveries to the European Union. Although misinformation about the AstraZeneca vaccine’s effectiveness in older people did not directly compromise the perceived safety of the inoculation, it arguably created sufficient doubt so that when the reports of thrombotic side effects emerged shortly thereafter, Europeans’ perceptions of the AstraZeneca vaccines became overwhelmingly negative.

The prime minister of the German state of Bavaria, Markus Söder, captured the accumulated public distrust when he said that “at AstraZeneca we can expect some new problem every day,” and suggested that the vaccine should be given to “whoever wants it and who dares to do it.”

Fortunately, the European public’s negative safety perceptions of the AstraZeneca vaccine have not spilled over into the main alternative vaccines produced by Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna. There is no evidence that general vaccine hesitancy has increased in Europe. On the contrary, public confidence in the safety of the Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna vaccines has increased in large EU member states since the beginning of 2021. This increase in confidence is echoed globally. As more countries roll out vaccines, and as more and more people get the shots, the more “normal” vaccination becomes. A widespread rollout of vaccines thus tends to create its own momentum and increasing public support. Data from The Economist in late July showed a continued decline in vaccine hesitancy in more than a dozen countries —with the sole exception of the United States.

Researchers at the University of Oxford developed a highly effective and life-saving vaccine. Unfortunately, its reputation has been compromised through a perfect storm of misinformation, corporate dissembling, and a fallout from nationalism. In the European Union, AstraZeneca’s breach of contract created fertile ground for misinformation that has severely compromised EU citizens’ trust in the vaccine, that extends even to its political leaders. And in the United Kingdom, the twin lenses of nationalism and Brexit in the tabloids and among the public caused widespread ignorance about the European Union’s crucial role in the British vaccine rollout—but, ironically, also sustained confidence in the vaccine.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: AstraZeneca, Coronavirus, European Union, United Kingdom, vaccines

Topics: Disruptive Technologies