First came global warming. Then hurricanes. Then more migratory bird deaths?

By John Morales | October 4, 2021

Yellow Warbler photographed at Cabo Rojo, Puerto Rico. This migrating bird breeds in North America and winters in Central/South America and the Caribbean. Image courtesy of Luis O. Nieves

Yellow Warbler photographed at Cabo Rojo, Puerto Rico. This migrating bird breeds in North America and winters in Central/South America and the Caribbean. Image courtesy of Luis O. Nieves

Four-hundred-million birds or more are forecast to be in flight tonight across the United States. That’s right: 400 million!

Birds’ annual migrations represent some of the most spectacular movements of animals on our planet, with enormous numbers of individuals moving hundreds, thousands, and even tens of thousands of miles annually. Birds that migrate annually between their breeding grounds in the North American temperate, or Nearctic, latitudes and their Neotropical wintering grounds in the Caribbean, South and Central America number in the billions. This Nearctic-Neotropical system, as it is known, evolved as the North American climate changed over the past 65 million years, as what was once a continent-wide belt of relatively mild and moist conditions gradually differentiated into a patchwork of tundra, woodland, grassland, and deserts with more extreme temperature and precipitation regimes. Birds started to migrate seeking gentler climates, better resource availability, and less competition or predation.

Avian habitats, migratory corridors, and resting and refueling stops can all be affected by the weather. Although migrating birds possess an impressive set of weather-sensing skills—including the abilities to assess changes in wind, visibility, and moisture in the air, as well as barometric pressure—they may not always be able to avoid unfavorable and severe weather, particularly when they must travel over water.

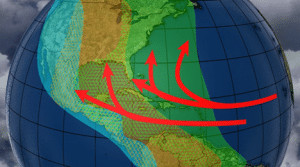

The Gulf of Mexico is one of the busiest bird migration corridors in the Western Hemisphere. More than half of the North American species that winter in the tropics must negotiate the Gulf of Mexico by flying over or around it twice yearly. Analysis of weather radar imagery has revealed that approximately 4 billion migratory birds are estimated to pass through there each year. Of the total bird biomass migrating to the Neotropics in the fall, an estimated 76 percent returned in spring—a net loss attributed to mortality during migration and the overwintering period.

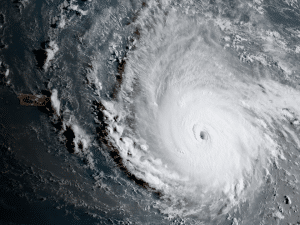

Hurricanes have been known to displace or kill birds—an outcome often termed a bird “wreck.” The most common Atlantic hurricane paths cross all or portions of all the Nearctic-Neotropical migrant bird flyways. In his 2020 book A Furious Sky: The Five-Hundred-Year History of America’s Hurricanes, Eric Jay Dolin relays historical accounts of birds displaced by hurricanes.

South of Cuba in October 1780, the British Royal Navy’s HMS Phoenix braced for a storm that was rapidly closing in after having leveled Jamaica. First Lt. Benjamin Archer noticed birds “dropping out of the sky and diving toward the deck, where many of them were knocked unconscious.” Similarly, in the Great September Gale of 1815, which hit Long Island and New England, lexicographer Noah Webster noted how sea spray in Massachusetts had been transported far inland along with seagulls, “some of which were blown all the way to Worcester, about 45 miles from the ocean.” In 2005’s Hurricane Wilma, thousands of Chimney Swifts were killed or displaced thousands of miles, leading to a significant decline in the breeding population.

Radar and ground observations showed that in 2011, Hurricane Irene sent tropical-dwelling birds as far north as upstate New York. Now, the rapidly changing climate is supercharging this sizeable threat to migrating birds: The proportion of tropical storms reaching high to extreme intensities and classified as Category 3, 4, and 5 cyclones globally is on an upward trend.

Knowing whether Nearctic-Neotropical bird migrants are being killed or displaced by Atlantic-basin hurricanes is particularly important today. Last week, federal wildlife officials declared 23 species extinct, including 11 birds—the well-known ivory-billed woodpecker among them. North American avifauna has decreased by nearly 30 percent in the last half-century—a staggering loss of nearly 3 billion birds. Even a small increase in deaths among birds that winter south of the United States could lead to significant added population declines.

While a handful of studies have shown that Atlantic tropical cyclones can harm the populations of some migrant bird species, there have been no comprehensive measure of the effect of tropical cyclone activity on regional or large-scale changes in migration intensity, until now. Earlier this year, thanks to the encouragement and guidance of mentors Andrew Farnsworth and Benjamin Van Doren at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, and a lending hand from Phil Klotzbach at Colorado State University’s Tropical Meteorology Project, I studied the influence of tropical cyclone activity on Nearctic-Neotropical bird migrants for my thesis at Johns Hopkins University.

An inverse relationship between the number of migrating birds over or near the Gulf of Mexico in spring and the frequency and intensity of active hurricanes in the preceding late summer and fall suggested a correlation between direct storm mortality and bird numbers. In other words, stronger and more frequent hurricanes in the gulf have been expected to mean more dead birds during migration season. This makes intuitive sense, but my fellow researchers and I wanted to actually prove it in the world of science. Our study applied emerging techniques in weather radar signal processing to compare the number of migrating birds in the fall to those returning in the spring, looking at common migration corridors near and over the Gulf of Mexico and parts of the US Atlantic coast beginning in 1995—when modern-day Doppler weather radar was commissioned in the United States.

The results of my research, which is not peer-reviewed yet, showed that very active hurricane seasons are associated with a reduction in the number of Neotropical migrants that return the following spring. When Atlantic hurricane seasons were very active (that is, stronger than 90 percent of typical hurricane seasons), the number of birds passing over and near the Gulf of Mexico during the following spring was approximately 20 percent lower compared to what happened when the migrations follow hurricane seasons with very low storm activity (in other words, a hurricane season that was weaker than 90 percent of hurricane season activity).

While this finding might imply that storms directly impacted or even wrecked birds, my additional research into storms that formed in subregions of the Atlantic confounded that premise. While increased tropical cyclone activity measured over the open North Atlantic Ocean was tightly associated with declines in migratory passage, the relationship between storm activity in the Gulf of Mexico itself and the number of birds migrating over the Gulf is weak, despite its status as the home of many major bird migration corridors. The same was true when looking at bird migrations over the Gulf of Mexico after storms in the Caribbean—there was little effect to be seen. So, there is more than just a single, simple, one-on-one, direct cause-and-effect relationship going on between storms, mortality, and observed passage fluctuations. Instead, it is likely that a combination of factors cause bird losses, only one of them possibly being direct storm impacts—though even that is not entirely clear from the results so far.

Thermo-imaging cameras are sometimes used to capture infrared images of birds flying at night.

What could be happening here is what researchers refer to as a “teleconnection,” meaning that there is a causal connection between short-term climatic patterns in one place and meteorological or environmental conditions that subsequently occur far away in some other locale. The teleconnection between El Niños or La Niñas in the eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean with hurricane activity thousands of miles away in the North Atlantic Ocean is one, well-understood example of this.

These short-term climate variations also impact rainfall accumulation in Neotropical bird wintering grounds and winds across migration flyways—environmental conditions which in turn can affect overall bird migrant fitness or survival. While the typical decrease in Atlantic tropical storm activity during an El Niño year might mean fewer migrating birds encounter stormy weather in the fall, the birds could also run into drier wintering grounds with a reduced carrying capacity when an El Niño is occurring. Said another way, short-term climatic variability patterns that drive Atlantic hurricane season activity also affect rainfall amounts in the wintering grounds (plus winds across migration flyways) which in turn may harm overall migrant fitness or survival.

Because birds can be affected by one or more of these and other teleconnecting factors (such as droughts, winds, and storms), it is difficult to measure the relative impact of each meteorological pattern on the migrating birds—much less the combined net effect when many of them occur at once. Some are favorable and others unfavorable for birds. The full spectrum of variables hitting migrating Neotropical birds has yet to be unraveled. Other teleconnections that could impact bird migrations might also come into play, such as the North Atlantic Oscillation.

Regardless of the underlying mechanisms, my finding that whole-Atlantic hurricane activity in the late summer and fall hurts the number of Neotropical migrating birds that return across and near the Gulf of Mexico in the spring stands as a first step, one which will hopefully launch further investigations. The methods employed in my research can be readily replicated, which means that by the year 2025 it will be possible to have a statistically robust dataset that can encompass 30 years of Doppler radar information—enough to be of significance to future scientists. So, this opens the door for other scientists to take on such a study.

Beyond problems posed by the expanding human footprint, birds are facing increasing challenges due to human-made changes to the climate. For the Neotropical long-distance migrating birds that rely on higher survivorship, any increase in mortality can have important long-term implications on populations. Continuing research into the connections between weather, climate, and birds can be invaluable for understanding avian behaviors as well as the mechanics of ecosystems.As we aggregate this knowledge, the emerging subdiscipline of aeroecology—the study of how airborne lifeforms interact with the atmosphere—could result in improved conservation strategies to steady or reverse the present downward trends in bird populations.

Rachel Carson once said that “[T]here is symbolic as well as actual beauty in the migration of the birds … something infinitely healing in the repeated refrains of nature.” But stronger hurricanes driven by a changing climate and other man-made hazards threaten to mute the chorus of this great wonder of the natural world.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: El Nino, La Nina, North Atlantic Oscillation, birds, climate change, climate crisis, global warming, hurricanes, migration, severe weather

Topics: Analysis, Climate Change, Columnists, Personal Essay