Illustration by Thomas Gaulkin

Are cities ready for extreme heat?

By John Morales | July 18, 2022

Four more people died that night. In the morning the sun again rose like the blazing furnace of heat it was, blasting the rooftop and its sad cargo of wrapped bodies. Every rooftop and, looking down at the town, every sidewalk was now a morgue. The town was a morgue, and it was as hot as ever, maybe hotter. The thermometer now said 42 degrees, humidity 60 percent.

—Kim Stanley Robinson, from The Ministry for the Future

The first chapter of Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry for the Future takes my breath away. Not just because I can almost feel the heat and humidity dripping off the pages, but because I know that—although the story is fictional—similar scenes are already playing out in real life.

This April, in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, the temperature shot up to 45.9 degrees Celsius, or 114.6 degrees Fahrenheit, during a prolonged heat wave that wilted crops and killed at least 100 people (a likely undercount). While spring heat waves are not uncommon in parts of India, according to the country’s Ministry of Earth Sciences they are happening more frequently. Twelve of the country’s 15 hottest years on record have occurred since 2006. A June 2015 heat wave killed over 2,000 people. It’s perhaps no coincidence that The Ministry for the Future begins in Uttar Pradesh. Is truth stranger than fiction?

Heat is the silent killer. It doesn’t roar like the winds in a hurricane or tear roofs off homes like a tornado. But it is deadly, all the same. In the United States, heat kills more people than any other weather hazard. As global warming drives average temperatures higher, dangerously hot episodes can be expected to proliferate. It is extremely unlikely that temperatures could have reached their deadly-hot levels in India without manmade global warming—levels that researchers say were made 30 times more likely by the climate crisis.

Some 70,000 dead across Europe in a 2003 heat wave. Up to 56,000 in Russia in 2010. North America’s most memorable heat waves in recent years include one in greater Chicago in 1995 that killed at least 700 people, and a “heat dome” event last year that killed hundreds in the Pacific Northwest and British Columbia.

37%

Percentage of heat-related deaths attributable to global warming since 1991

Heat-related deaths are up across all continents over the last three decades. Since 1991, research published in Nature Climate Change found that approximately 37 percent of those can be attributed to manmade global warming. In the United States alone, hotter temperatures could lead to 110,000 premature deaths per year by the end of the century if warming continues unabated, a Geohealth study asserts.

Which is why the most popular measure of heat stress on the human body—the heat index—is being reevaluated for the hotter Anthropocene.

37%

Percentage of heat-related deaths attributable to global warming since 1991

Source: D. Shindell, et al. (2020). “The effects of heat exposure on human mortality throughout the United States.” GeoHealth, 4. (See also for maps of projected heat-related mortality under other climate change scenarios.) Maps by Thomas Gaulkin.

Off the charts. The heat index is “what the temperature feels like to the human body when relative humidity is combined with air temperature,” according to the National Weather Service. Bodies perspire to cool off, but sweat doesn’t evaporate as easily when the air is full of moisture, so a combination of high temperature and high humidity keeps the body from properly regulating itself. For example, if the air temperature is 98 degrees Fahrenheit and the relative humidity is 70 percent, it feels like it’s 134 degrees Fahrenheit.

The legacy heat index table stops at values at which the body can no longer cool itself by sweating. This can happen when either the air becomes supersaturated, or the skin does. But sweat can also drip off the body. If that is taken into account, scientists can extend the heat index beyond its current limits, which will be useful for estimating regional health outcomes on a warmer planet.

Hotter and more humid conditions are already here and with no immediate end in sight to rapid climate change, temperatures by the end of this century could average 8 degrees Fahrenheit above what they were at the beginning of it. That would push the range of the highest heat index values beyond what the scale allows for today and into the truly unsurvivable range.

The same 46-degree Celsius reading observed in Uttar Pradesh this spring, accompanied by a relative humidity value of 50 percent, would yield a whopping 82 degrees Celsius or 180 degrees Fahrenheit feels-like temperature in the new “extended heat index” table. According to the authors of the UC Berkeley paper that proposed the augmented heat index, at these levels “it is impossible to maintain a healthy core temperature.” Those kinds of calamitous days are expected to increase, especially in large metropolitan areas.

As average temperatures increase, so does the incidence of extreme heat. Climate Central’s new Climate Shift Index indicates how much climate change has altered the frequency of daily temperatures at a particular location. (Courtesy of Climate Central)

Heat islands. When you think of extreme heat, you might think of a desert. But there is a worse place to be stuck during a heat wave: a city. Cities generate excess heat, a process called the urban heat island effect. Contributing factors include excess warmth generated by car engines, air conditioners and other equipment, as well as the lack of evaporative cooling from rainfall runoff that is removed by design as quickly as possible from the urban core. Consequently, city temperatures can run 15 to 20 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than neighboring rural areas. New Orleans, Newark, New York, and Houston are all cities with especially large heat island effects.

Thermal infrared satellite data of New York City, measured by NASA’s Landsat Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus on August 14, 2002. Where vegetation is dense, temperatures are cooler. (Images by NASA/Robert Simmon)

Lack of vegetation compounds the problem for residents of hotter cities, exacerbating existing inequalities. “The heat islands in the city—the places where it gets really hot because there are no trees—are disproportionately concentrated in poor neighborhoods. And that leads to, along with a host of other factors, really negative health outcomes,” says Mario Alejandro Ariza, author of Disposable City: Miami’s Future on the Shores of Climate Catastrophe.

Trees not only provide shade, but can also cool areas by nearly 2 degrees Fahrenheit through the process of transpiration. Wealthier neighborhoods are often leafier than poor neighborhoods, and a dearth of trees in cities and suburbs can be linked to historically racist practices like redlining. In most cities in the United States, the disparity is shocking.

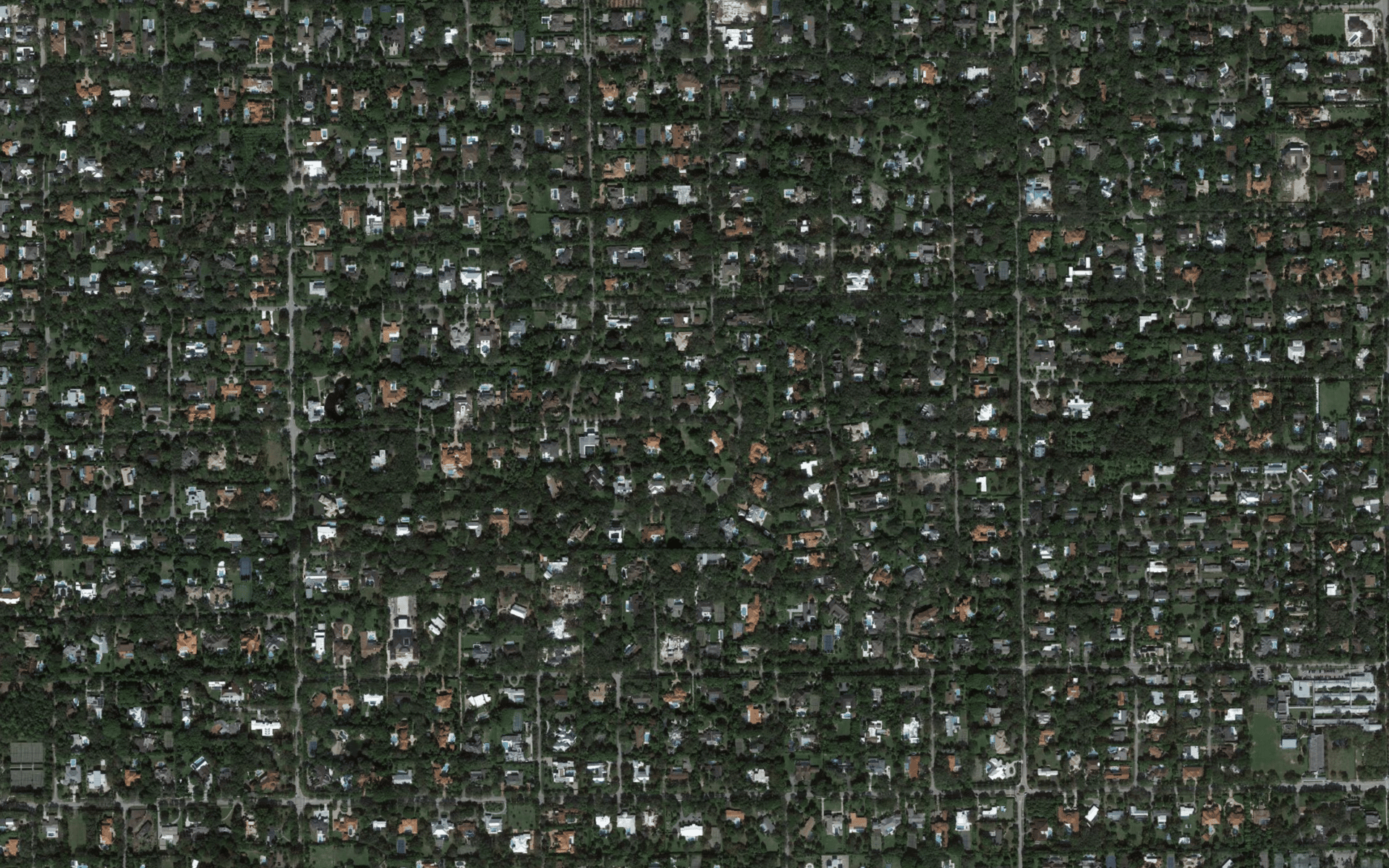

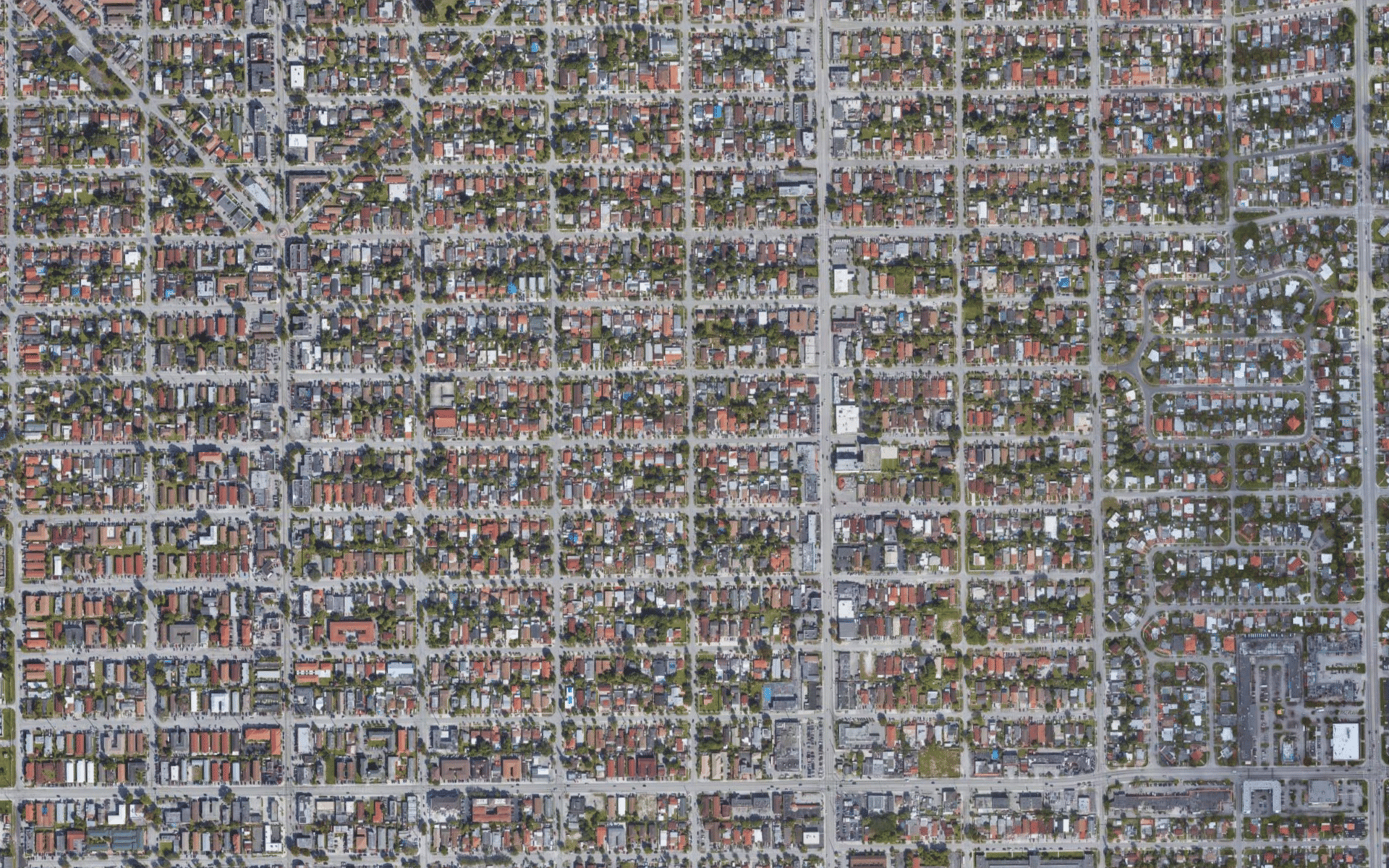

For example, in greater Miami, Florida, wealthy enclaves like Pinecrest have seven times the tree canopy of blue-collar municipalities like Hialeah. Consequently, surfaces in Hialeah average 14 degrees hotter than those in Pinecrest in the middle of the day.

15-20°F

How much hotter cities often are than nearby rural areas

This interactive comparison of two Miami-area neighborhoods shows how income inequality often coincides with unequal tree canopies, making vulnerable communities hotter and even more vulnerable. According to census.gov, the median income in Pinecrest (left) is $164,419. It is $38,471 in Hialeah. (Satellite images via Google Earth)

In response to this growing crisis, cities are racing to tackle the challenge of rapidly rising temperatures. Miami-Dade County, Florida—with a population of 2.7 million people spread across a large megalopolis—was the first population center to name a Chief Heat Officer last year. Phoenix and Los Angeles followed suit, as well as Athens, Greece, Monterrey, Mexico, and Santiago, Chile.

One of the first things Miami-Dade’s Chief Heat Officer Jane Gilbert proposed was for the National Weather Service in Miami to lower the threshold for the issuance of an official Heat Advisory from 108 degrees Fahrenheit to 105 degrees Fahrenheit. “Most of our heat-related deaths happen at thresholds lower than the 108 threshold, not because it’s a higher risk at the heat index of 105 or 102, but because we just have that many more days at that heat index below 108,” Gilbert says.

Gilbert is talking about chronic high heat, which in addition to putting the elderly and young children at risk, may also threaten outdoor workers and people taking certain prescription or illicit drugs. High heat—or a “feels like” temperature of 105-degrees Fahrenheit, which has historically been observed in Miami-Dade approximately seven days a year, may be experienced nearly three months a year in the not-so-distant future.

81

Additional annual days of high heat ("feels like" temperatures over 105°F) forecasted for Miami-Dade county by midcentury

Between 2015 and 2019 there were 85 times more heat-exacerbated fatalities in Miami-Dade than were recorded on death certificates, according to a study commissioned in part by the county. It’s hard to fathom how many more will die when heat indexes reach dangerous levels on nearly 90 days a year.

Yes, air conditioners are nearly ubiquitous in South Florida. But the unhoused and the air conditioning insecure—anyone who must choose between putting food on the table and paying the electric bill—are still exposed to high heat index values. In prolonged power outages, like those brought on by hurricanes, the heat danger extends to everyone. Twelve nursing home patients died in a suburb of Fort Lauderdale during the blackout after Hurricane Irma in 2017—a small fraction of over 400 nursing home deaths across the state of Florida in the aftermath of that storm.

Awareness of the threats to human health posed by high heat along with timely warnings about imminent heat waves can go a long way in keeping people out of the hospital, or worse. Naming heat waves may prove to help the public personalize and internalize the threat in hot places like Seville, Spain.

81

Additional annual days of high heat ("feels like" temperatures over 105°F) forecasted for Miami-Dade county by midcentury

7.4 million

Number of lives saved globally if the United States achieves net-zero emissions by 2050.

Moving people to cooling centers—malls, for example—is one of the emergency actions local authorities can take during singular heat wave events. But as longer and longer episodes of elevated temperatures start to morph into chronic high heat, city leaders must find ways to permanently try to counter the rise in temperature driven by global warming.

Shade and transpiration from trees can cool surface temperatures by up to 20 degrees Celsius (36 degrees Fahrenheit) compared to those exposed to the sun. In Miami-Dade County, Jane Gilbert and the Resilient305 Collaborative are looking to increase the urban tree canopy from a paltry 20 percent to a more acceptable (but bare minimum) of 30 percent through, among other things, tree giveaways. The plan is to prioritize areas that currently have the lowest tree canopy.

Cities can also add engineered shade, like bus stop canopies and covered playgrounds. Those shade structures can’t cool surfaces as much as trees, but still can subtract 10 to 15 degrees Celsius (18 to 27 degrees Fahrenheit) compared to unshaded areas. As Gilbert says, “all shade is good.” Spread across hundreds of cities across the United States, these local adaptations will be crucial in saving thousands of lives.

Worldwide, millions that would otherwise succumb to high heat could be saved if countries implemented policies that reduced and stopped the burning of fossil fuels. The United States alone could save 7.4 million souls across the planet if it reached President Biden’s goal of net-zero emissions by 2050, a study by the Climate Impact Lab consortium estimates. This doesn’t even take into account other climate hazards—just heat. Acting on the climate crisis today at the local, national, and international level can keep millions from morbidity and death.

Heat is silent. You don’t have to be.

7.4 million

Number of lives saved globally if the United States achieves net-zero emissions by 2050.

As the Russian invasion of Ukraine shows, nuclear threats are real, present, and dangerous

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent, nonprofit media organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: cities and climate change, climate adaptation, climate crisis, extreme heat, extreme weather, global warming, heat dome, heat wave

Topics: Climate Change, Columnists

Share: [addthis tool="addthis_inline_share_toolbox"]

The heat death of humans has never been considered in our future.

The urban heat island effect, why an urban or metropolitan area that is significantly warmer than its surrounding rural areas due to human activities. https://youtu.be/WK5_MxOWKEI

I have two issues with this article

1) The worst case scenario (high emissions no mitigation) is used as a reference. I believe this scenario is no longer valid based on existing emission reductions.

2) Hialeah is further from the ocean than Pinedale. The graphic makes it appear they are next to each other. So it isnt all about trees

I am an engineer and have always looked at data sources with a great deal of skepticism. It served me well. Is the reporter an activist or a neutral reporter of unbiased information?