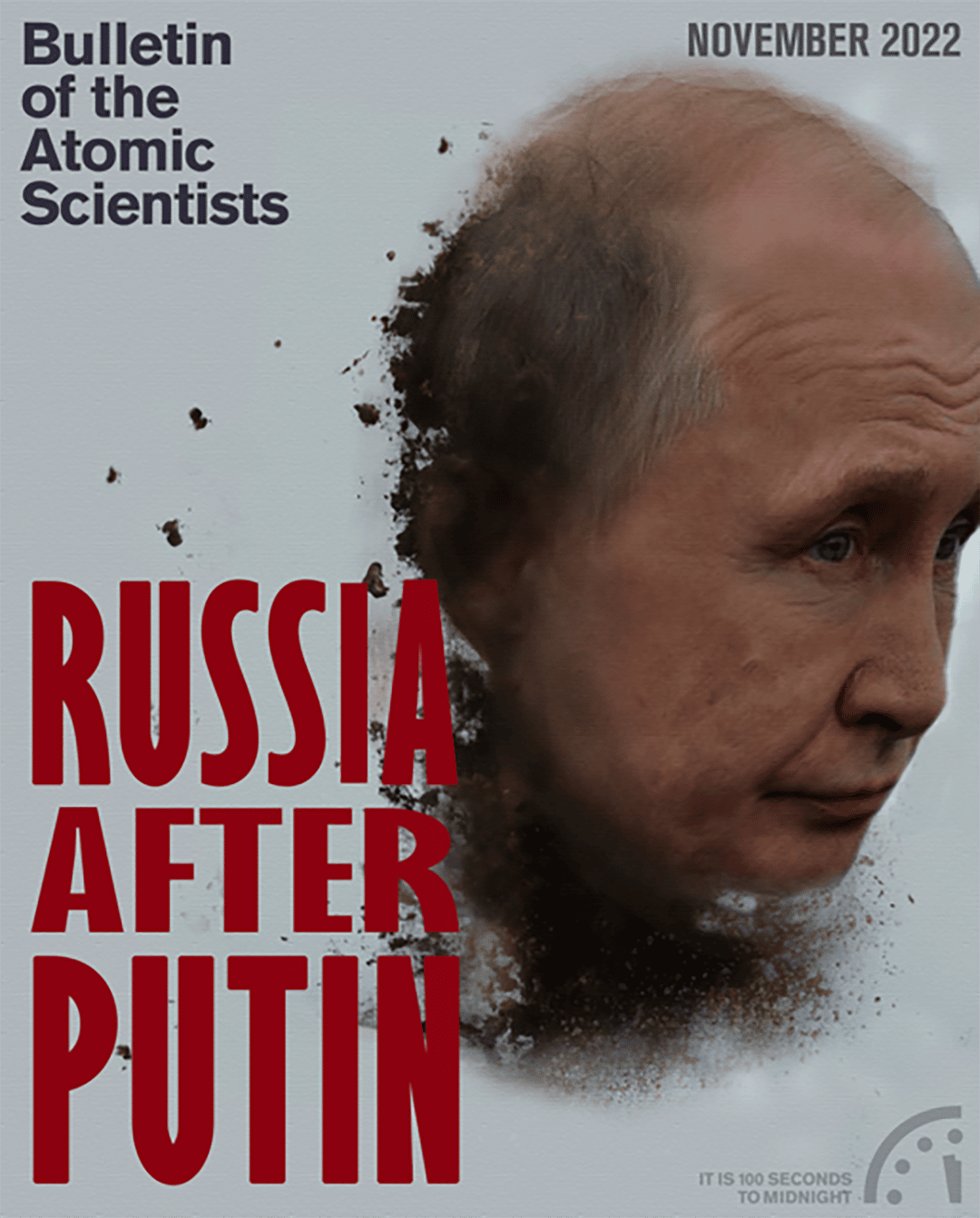

Nuclear Notebook: The long view—Strategic arms control after the New START Treaty

By Jessica Rogers, Matt Korda, Hans M. Kristensen | November 9, 2022

Nuclear Notebook: The long view—Strategic arms control after the New START Treaty

By Jessica Rogers, Matt Korda, Hans M. Kristensen | November 9, 2022

The Nuclear Notebook is researched and written by Hans M. Kristensen, director of the Nuclear Information Project with the Federation of American Scientists (FAS), and Matt Korda, a senior research associate with the project. This edition features unique contributions from FAS Impact Fellow and international lawyer Jessica Rogers. The Nuclear Notebook column has been published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists since 1987. This issue examines the topic of strategic arms control after the expiration of the New START Treaty in February 2026. We explore potential avenues for constructive engagement between the United States and Russia and consider how to optimally balance arms control options that are legally possible and politically feasible. This article is freely available in PDF format in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ digital magazine (published by Taylor & Francis) at this link. To cite this article, please use the following citation, adapted to the appropriate citation style: Hans M. Kristensen & Matt Korda, The long view: Strategic arms control after the New START Treaty, 2022, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 78:6, 346-367, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2022.2133287 To see all previous Nuclear Notebook columns, go to https://thebulletin.org/nuclear-notebook/.

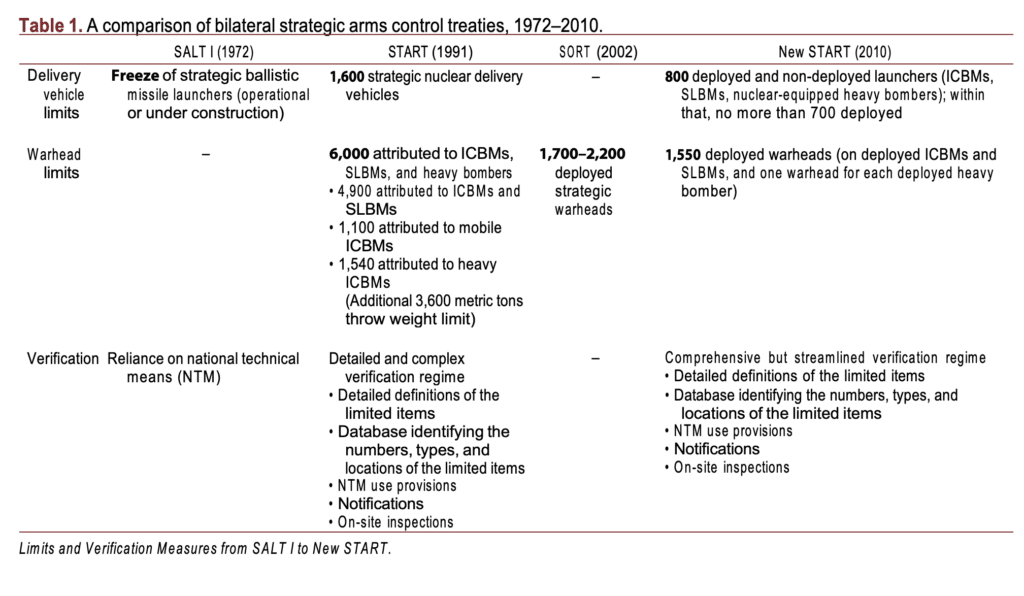

It is no secret that arms control is becoming a lost art. While the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s were filled with strategic arms control talks, only one treaty limiting nuclear arsenals has entered into force over the past two decades: New START (the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty). Notwithstanding the innovations in its verification regime, the treaty relied heavily on the existing principles of the original START Treaty, together with many of the core players’ experiences negotiating and ratifying it 20 years earlier.

Since then, however, Russia’s Putin era and, with it, the growing distrust between Russia and the United States, as well as the retirement of Cold War and post-Cold War arms control experts, have stalled any progress. Other treaties such as the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF Treaty) have been abandoned, and other nuclear-armed states remain outside arms limitation agreements. Despite new technologies and a new security architecture requiring more thought than ever before, substantive proposals and good faith negotiations have been replaced by empty talking points. Additionally, in recent years both the United States and Russia have engaged in unconstructive blaming and shaming efforts, which have further soured the arms control environment and lowered the political will for pursuing negotiations in good faith.

Unless both Russia and the United States soon advance proportional efforts to overcome these forces, it is only prudent to expect that February 4, 2026 will be the last day of bilateral strategic arms control (Albertson 2021, 78). As a first step, the United States and Russia, on August 25, 2022, submitted a statement to the Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT Review Conference) committing to “pursue negotiations in good faith on a successor framework to New START before its expiration in 2026, in order to achieve deeper, irreversible, and verifiable reductions in their nuclear arsenals” (2020 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons 2022). But that commitment so far appears to be blocked by the dispute over Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Treaty history

1972/1979: Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT I and II)

Nuclear arms limitation treaties emerged during a period of intense buildup of US and Soviet strategic nuclear forces. In the late 1960s, the United States realized that the Soviet Union was building up its intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) forces to reach parity with the United States and had also begun to construct a limited anti-ballistic missile (ABM) defense system around Moscow. Concerned that Russia might eventually be able to launch a first strike and then block US retaliation, President Lyndon Johnson called for strategic arms limitations talks (SALT). The hope was that US-Soviet relations could be stabilized through limits on the development of both offensive and defensive strategic systems (US Department of State 2022).

By 1972, the Soviets were convinced that defensive systems had limitations, allowing the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty and SALT I to be negotiated and enter into force. SALT I was considered an interim agreement that consisted of a simple freeze, not yet including on-site inspections. Its verification relied on national technical means, referring to intelligence satellites and related capabilities. However, the term was officially left undefined to protect intelligence methods and avoid offending Soviet sensibilities (Gottemoeller 2021, 2; Aftergood 2019).

In 1979, the United States and the Soviet Union completed the negotiation of SALT II which set a limit of 2,400 strategic nuclear delivery vehicles (including ICBMs, submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), and heavy bombers), banned the construction of new ICBMs, and limited the number of multiple independently-targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs) to 1,320. However, the treaty never entered into force due to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan as well as some US senators’ criticisms of the Soviet Union’s crackdown on internal dissent, the Soviets’ increasingly interventionist foreign policies, the treaty’s verification process, and SALT II’s failure to sufficiently limit Soviet MIRV technology that would allow missiles to carry multiple warheads (US Department of State n.d.; Cameron 2022). Nonetheless, both sides agreed to voluntarily observe the SALT II-negotiated limits in subsequent years (US Department of State n.d.).

As former US Secretary of Defense and former Director of the Central Intelligence Agency Robert Gates noted, the process itself was likely the most useful part of these talks: “For the first time, the two sides sat down and began a dialogue about their nuclear weapons and, implicitly, their nuclear strategies. Military and civilian leaders on both sides were able to take the measure of one another and, at the same time, engage their political leaders in an unprecedented way in learning about the balance of terror” (Gates 1996, 45).

1991: Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START)

Partially due to the further development of MIRV technology on both sides, the Americans and Soviets realized that strategic systems had to be reduced to prevent either side’s out-deployment in warhead numbers. This realization led to the 1980s Strategic Arms Reduction Talks (START), which eventually became the first ratified treaty that required US and Russian reductions—rather than a mere freeze—of strategic nuclear weapons. The START Treaty, signed in 1991 with entry into force three years later, limited both countries to 1,600 strategic nuclear delivery vehicles and 6,000 warheads attributed to ICBMs, SLBMs, and heavy bombers, and included more detailed sub-limits. Once Russia believed that the benefits of on-site inspections outweighed their concerns over giving the United States reciprocal access, nothing was standing in the way of a verifiable arms control treaty to create more predictability. The detailed verification regime of START, including databases, notifications, and on-site inspections, allowed both sides to better calculate necessary deterrence investments while preventing an arms race (Gottemoeller 2021, 3).

The United States and Russia subsequently negotiated and signed START II in 1993, committing to additional reductions down to 3,000 to 3,500 strategic nuclear warheads on ICBMs, SLBMs, and heavy bombers by the end of 2007. Importantly, the treaty included a ban on multiple warheads on ICBMs. While the treaty never entered into force despite a decade-long bilateral effort, it strongly shaped the US Strategic Command’s long-term force structure planning (Kristensen 2001, 12).

2002: the Moscow Treaty (SORT)

Under the Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty (SORT), also called the Moscow Treaty, Russia and the United States agreed in 2002 to further reduce their nuclear arsenals to between 1,700 and 2,200 operationally deployed strategic warheads each by December 31, 2012—a nearly two-third reduction from the START I limits. While progressive in its numerical limits, SORT was a very simple treaty, with its text barely exceeding one page and not providing any separate verification measures. Instead, Russia and the United States decided they would continue to rely on START to provide verification until its expiration in December 2009 (US Department of State 2002).

2010: the New START Treaty

Finally, the New START Treaty (officially the “Treaty between the United States of America and the Russian Federation on Measures for the Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms”) succeeded in further limiting the US- and Russian- deployed long-range nuclear forces down to 1,550 warheads and 700 delivery vehicles—the lowest in over 60 years. For that purpose, New START for the first time counted the actual number of warheads found on deployed ICBMs and SLBMs, rather than mathematically calculating numbers based on missile tests as in START. Since bombers do not carry nuclear weapons under normal circumstances, each deployed heavy bomber was attributed one warhead by default to make bombers accountable under the treaty (US Department of State 2010). Therefore, the warheads attributed to bombers do not reflect actual warhead loads—unlike for missiles. Delivery vehicles under New START encompass deployed ICBMs, SLBMs, and heavy bombers equipped to carry nuclear armaments. It was not until far into the negotiations that Russia and the United States determined these numbers, with Russia originally asking for more warheads while the United States requested more delivery vehicles to protect its advantage in that area (Gottemoeller 2021, 34).

In addition to the further reduction of these limits, New START created an entirely new limit of 800 deployed and non-deployed launchers. Although this concept was originally introduced by Russia, the United States later embraced the idea as it would, first, prevent Russia from building and storing unlimited numbers of mobile missile launchers since these would count toward the non-deployed limit, and, second, provide the United States with the flexibility to convert bombers to conventional use and overhaul submarines since these would not count under the deployed limits during those processes (Gottemoeller 2021, 83, 112).

Another aspect of New START’s flexibility is the preserved “freedom to mix,” where each side can decide the composition and structure of its strategic offensive forces if it stays below the total limits. Russia, being a great land power, could continue to rely primarily on ICBMs. On the contrary, the United States, being a sea power, was able to keep more SLBMs than Russia (Gottemoeller 2021, 32). The mix chosen by the United States included no more than 400 deployed ICBMs, no more than 240 deployed SLBMs, and no more than 60 deployed heavy bombers. Beyond an additional 100 non-deployed launchers, a significant number of excess launchers had to be denuclearized or destroyed. Because Russia had significantly fewer launchers than the United States, it did not have to reduce its deployed force.

Most importantly, however, the New START Treaty created what has often been referred to as the “gold standard” of verification: procedures governing the conversion and elimination of strategic offensive arms, the establishment and operation of a database of treaty-required information, transparency measures, a commitment not to interfere with national technical means of verification, the exchange of telemetric information, the conduct of on-site inspection activities, and the operation of the Bilateral Consultative Commission (BCC) (US Department of State 2022).

Innovations in New START’s verification regime managed to address both sides’ concerns about the old START treaty’s verification regime while better balancing information and burden—a core military interest on both sides.

First, it streamlined START’s more burdensome verification regime into two types of verifications: one for deployed systems (Type One) and the other for non-deployed systems (Type Two). They largely encompassed the aspects of previously separate types of inspections—resulting in slightly longer but much less frequent (up to ten Type One and up to eight Type Two) short-notice on-site inspections annually. This solution fulfilled both militaries’ interest in avoiding too frequent or overly intrusive inspections that could disrupt operational tempo for days (Gottemoeller 2021, 50).

Second, it enabled real-time tracking of each other’s forces by introducing unique identifying numbers for launchers and delivery vehicles, utilizing the existing serial numbers each country already used to track and account for its weapons. This gave inspectors a clear idea of the weapons they needed to find at each site (Gottemoeller 2021, 52).

Third, New START addressed rising cost and accuracy concerns about the conversion and elimination of certain weapon systems. To allow satellites to confirm eliminations, for instance, it determined space and time requirements for displaying eliminated missiles and other treaty accountable items and established the right to request reciprocal inspections of such. To address US concerns about overcounting delivery vehicles under the previous treaty, New START also introduced simplified measures to confirm US conversion and elimination processes, particularly the conversion of all B-1 bombers to conventional-only platforms, the conversion of submarine tubes, and the total elimination of B-52 bombers (Gottemoeller 2021, 121–122).

In the end, while Russia had originally urged for a simpler treaty like SORT, it has praised New START as the “gold standard” for verification (Alexander and Ferraro 2010).

The treaty entered into force on February 5, 2011, and provided the parties with seven years to reduce their forces to these agreed-upon limits. Both sides successfully met the central limits by February 5, 2018, and have since stayed at or below them. Russia and the United States extended the originally 10-year treaty to its maximum 15-year length, now set to expire on February 4, 2026 (US Department of State 2022).

Table 1 compares the limits and verification mea- sures from SALT I to New START.

The New START Treaty remains in force through February 4, 2026. If no follow-on agreement is concluded before its expiration, then February 5, 2026, will be the first day since 1972 without substantive, verifiable limits on the world’s two largest nuclear arsenals. In other words, anyone under the age of 54 will, for the first time, live in a world without strategic arms control.

Short of a new treaty, Russia and the United States would lose mutual predictability and trust. It would also mean that military planners would have to rely more on worst-case scenarios, subsequently accelerating defense spending that could result in an even more costly and unstable arms race.

Such a gloomy future is, of course, avoidable. The United States and Russia have several options available to maintain strategic limitations on their arsenals, including—in order of increasing resulting predictability but decreasing feasibility—continued adherence through mutual moratoria, the negotiation of a new executive agreement, or the conclusion of an entirely new treaty.

We explore each one of these three options in this issue. But, to illustrate the urgency with which both countries should pursue them, we first offer a realistic scenario of how US and Russian arsenals could evolve if the current trends remain unchanged—that is, if the last bilateral arms control treaty still active is allowed to expire without a follow-on agreement.

The arms race in high gear

Up until now, both countries have meticulously planned their respective nuclear modernization programs based on the assumption that both countries will not exceed the force levels dictated by New START. Without bilateral arms control, however, this planning will be thrown into an era of unpredictability and distrust. Both sides would need to reassess their programs to accommodate more uncertain nuclear futures. This would likely result in worst-case scenario planning based on fewer data points and the uncertainty of future force levels—including those that would likely exceed New START levels. This could drive significant increases in both countries’ arsenals, and ultimately lead to mutual accusations of arms racing and international accusations of NPT violations.

The United States and Russia each have significant numbers of additional nuclear warheads in storage that cannot be loaded on the launchers because of the New START limit of 1,550 deployed warheads. If New START fell away, these warheads could be uploaded in days, weeks, or months, depending on the type of launcher.

The United States has a significant upload capacity for its deployed missiles. Although all 400 of its deployed ICBMs currently only carry a single warhead, 200 of these use the Mk-12A reentry vehicle and are therefore capable of carrying up to three W78 warheads each. Moreover, the United States has an additional 50 “warm” ICBM silos which could be reloaded with missiles if necessary. If the 200 Mk-12A-equipped missiles were uploaded to three warheads each and the 50 reloaded missiles were also equipped with three warheads each, the ICBM force loading could potentially increase from 400 to 950 warheads. In the absence of treaty limitations, the United States could also upload each of its deployed Trident SLBMs with a full complement of eight warheads, rather than the current average of four to five. It could also reactivate the four launch tubes on each nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine (SSBN)—56 in total—that were disabled under New START. This could potentially more than double the number of deployed US SLBM warheads from approximately 944 today to approximately 2,300 warheads.

Either of these actions would likely take months to complete, particularly given the complexities involved with uploading additional warheads on ICBMs. Moreover, ballistic missile submarines would have to return to port for uploading on a rotating schedule. However, deploying additional warheads to US bomber bases could be done very quickly, and the United States could potentially upload nearly 700 cruise missiles and bombs on B-52 and B-2 bombers.

Russia also has a significant upload capacity, especially for its ICBMs. Russia’s 40 SS-18 Satan ICBMs can carry up to ten MIRVs; however, it is assumed that they have been downloaded to carry only five to meet the New START limitations. The incoming RS-28 Sarmat ICBM is also reportedly capable of carrying up to 10 MIRVs; however, it is assumed that these too will be downloaded upon their deployment if the New START force limits are retained. The SS-27 Yars is also assumed to have been downloaded from four MIRVs to three. As a result, without the limits imposed by New START, Russia’s ICBM force could potentially increase from approximately 812 warheads to approximately 1,185 warheads.

Submarine-launched ballistic missiles on Russian Borei-class SSBNs are also thought to have been downloaded from an estimated six warheads to four to meet New START limits. Without these limitations, the number of deployed warheads on Russian SSBNs could rise from an estimated 576 to approximately 800. As in the US case, Russian bombers could be loaded relatively quickly with hundreds of nuclear weapons. The number is highly uncertain but assuming approximately 50 bombers are operational, the number of weapons could potentially be increased to nearly 600.

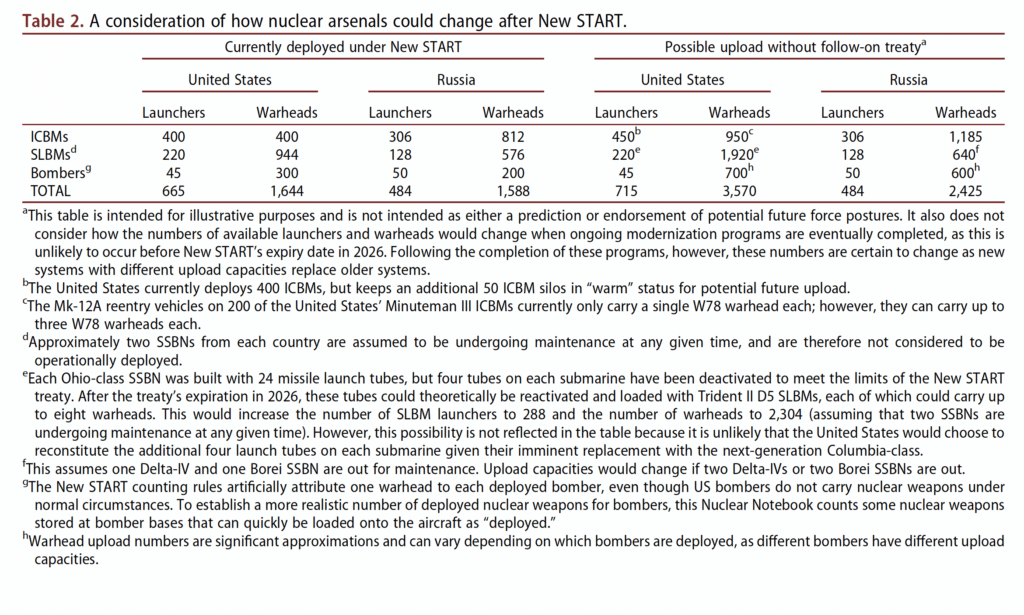

Table 2 considers how both US and Russian strategic nuclear forces could increase if New START is allowed to expire without a follow-on agreement in place. If both countries uploaded their delivery systems to accommodate the maximum number of possible warheads, both sets of arsenals would approximately double in size. The United States would have slightly more deployable strategic warheads but Russia would still have a significantly larger arsenal of operational nuclear weapons, given its sizable stockpile of nonstrategic nuclear warheads.

Table 2 presents a worst-case scenario for possible warhead uploads if New START is allowed to expire without any follow-on. Because of the relatively low estimated cost of a simple upload across the triad (about $100 million in one-time costs to the United States), this scenario is not impossible from a budgeting perspective (Congressional Budget Office 2020, 3).

In the longer term, both countries could theoretically go further and pursue costly larger expansions of their strategic nuclear forces, such as going back up to the START I level of 6,000 warheads each. Some voices in the United States have already raised doubts about the New START force limits because of China’s nuclear buildup (Miller 2022). Depending on the desired degree of flexibility and the cost of new strategic delivery systems, such an expansion could cost the United States, for instance, between $88 billion to $439 billion in one-time acquisition costs, plus $4 billion to $28 billion in annual operation and sustainment costs (Congressional Budget Office 2020, 3). This does not even include research and development costs or the Department of Energy’s costs to produce, sustain, or store more nuclear warheads. It is unclear what the costs of similar actions would be for Russia, but they are likely to also be very expensive.

Moreover, there are expected consequences beyond the offensive strategic nuclear forces that New START regulates. If the verification regime and data exchanges elapse, both countries are likely to enhance their intelligence capabilities to make up for the uncertainty regarding the other side’s nuclear forces. Both countries are also likely to invest more into what they perceive will increase their overall military capabilities, such as conventional missile forces, nonstrategic nuclear forces, and missile defense (Congressional Budget Office 2020, 7–9). These would all come with significant additional costs.

Overall, today’s technologies and the geopolitical situation would likely lead to a different style of arms racing than during the Cold War; however, it could similarly become unnecessarily costly and dangerous. Moreover, it could trigger reactions in other nuclear-armed states that might also decide to increase their nuclear forces and the role they play in their military strategies. The good news is that this future is certainly not inevitable—even without a formalized treaty structure beyond 2026. The following sections offer a series of options for both countries that would help prevent an escalation of the arms race. The estimated success of each option depends upon a variety of factors, including political will, legal complexities, and relative degrees of formalization. The following sections are listed in order of their projected feasibility, and thus begin with Plan C—the most feasible but least sustainable option—and end with Plan A —the most challenging yet most optimal outcome.

Plan C: continued adherence to New START’s core provisions beyond 2026

One option would be for both countries to simply continue abiding by the core provisions of the treaty—even without the treaty being formally in effect. Such a “gentleman’s agreement” could be made by the leaders of both the United States and Russia without legislative approval, as opposed to a formal treaty. By agreeing to not exceed the New START limits, each side could continue its current strategic force structure planning and therefore avoid a costly expansion.

Such an agreement, however, also comes with challenges. Practically, the United States and Russia could certainly continue to adhere to the treaty limits—much as they did for a brief period of four months in the interim between START and New START. But without the legal structure of a treaty, the main verification benefits of New START—data exchanges, notifications, and inspections —could be lost due to the legal difficulties surrounding classified information. This could force both parties to rely exclusively on national technical means for verification, which would severely strain both the resources and capabilities of their respective intelligence communities.

We now examine the feasibility of this option.

Could bilateral data exchanges and notifications continue after 2026?

Without a treaty framework to enable the legal exchange of otherwise classified or restricted nuclear weapons data, both Russia and the United States would need to prepare legal avenues to allow them to continue sharing this information. According to former New START chief US negotiator, Rose Gottemoeller, the United States continued notifications as a goodwill gesture and was willing to continue data exchanges during the bridge period between START and New START (Gottemoeller 2022). Given this precedent, it should again be feasible for the United States to legally arrange for data exchanges and notifications. On the other side, Russia did not continue reciprocal notifications during the interim period, despite its promise to continue abiding by the treaty’s limits. To that end, Russia will need to examine whether it might need to first amend its domestic laws concerning the sharing of classified nuclear information.

Could bilateral on-site inspections continue after 2026?

The question of on-site inspections continuing beyond the scope of a formalized treaty has been considered by Gottemoeller. In her book, Negotiating the New START Treaty, she notes that:

“The Russians also raised doubts about the legal status of such an agreement. According to them, they needed a full, legally-binding treaty, duly approved by their State Duma and Federation Council, in order to override their domestic law and permit foreign inspectors. According to the Russian state security law, no foreigners are allowed in sensitive nuclear facilities. A treaty can override that domestic law” (Gottemoeller 2021, 85–86).

The United States also has laws restricting the access of foreign nationals to sensitive military installations. These too could be overridden by an international treaty, as has been the case with New START.

It would theoretically be possible for both countries to change their domestic laws to enable on-site inspections to continue in the absence of a treaty framework. There is precedent for attempting this in the United States: In 2009, facing the possibility that START might expire without a follow-on treaty in place, Sen. Richard Lugar (R-IN) brought to the table a bill specifically designed to provide Russian inspectors with the ability to continue on-site inspections for seven months or until the entry into force of a new bilateral treaty—whichever came first (S.2727 2009). The bill was ultimately not passed, but its introduction to Congress suggests that a similar path could be considered again if necessary. Such a bill could specifically require the continued implementation of the expired treaty’s verification protocol and annexes that contain highly detailed instructions for how on-site inspections are to be conducted, including requisite flight paths, aircraft call signs, customs exemptions, lodging, accommodations, and the according of diplomatic immunity upon each party’s inspectors and aircrew, among other granular details.

In the absence of a follow-on treaty, rather than attempting to maintain all existing verification mechanisms, another option could be to reduce the scope of the verification regime altogether. While conventional wisdom holds that more verification is always better, recent scholarship indicates that this may not always be the case. In his doctoral dissertation, political scientist Andrew Reddie posits that “the most intrusive types of verification are not, as is currently believed, more likely to lead to compliance” (Reddie 2019). Instead, Reddie’s analysis—based on more than 1,000 agreement-years of historical data—suggests that highly intrusive inspections could yield a statistically significant greater likelihood of noncompliance than less intrusive types of verification regimes. Reddie suggests that this phenomenon could be the result of a “surveillance bias,” in which it is possible that “a hammer (representing a verification regime) will constantly search for and find a nail (noncompliance). Thus, those agreements that have a more stringent verification mechanism—a larger hammer—may have a higher probability of detecting non-compliance” (Reddie 2019).

If a reduction in the intrusiveness of the treaty’s verification regime would not necessarily increase the likelihood of noncompliance, both parties could use the opportunity of New START’s expiration to possibly reduce the invasiveness of future verification mechanisms. This would avoid unwanted challenges triggered by the loss of the treaty’s inspection protocols once it expires while continuing to adhere to its core provisions and central limits. For example, the United States and Russia could place a hold on conducting Type One and Type Two inspections but continue to exchange compliance data and promise not to interfere with the other party’s national technical means of verification.

Even though after New START expires there would be no legal requirement to comply with the treaty’s core provisions, both countries would still likely have strong normative and geopolitical incentives to continue doing so. This is partially because of the risk—even without on-site inspections—that any increase would be detected and exposed by the other side’s national technical means. Moreover, during the treaty’s history, there have been several extended periods when Type One and Type Two inspections were suspended—most notably during the Covid-19 pandemic, when inspections were paused for nearly two years. During these periods there were no accusations of noncompliance by either side.

A reduction of the verification regime may not necessarily create a compliance problem, but it could create a political one. Historically, Congress has been more amenable to support and provide the resources to implement agreements with robust verification regimes, whereas agreements with relatively looser verification mechanisms, such as SORT or the US-Iran Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), have faced fierce resistance. This challenge could be exacerbated by relying exclusively on national technical means for verification, which could potentially result in the intelligence community issuing ranged estimates of Russian warheads and delivery systems rather than knowing the exact numbers of warheads and launchers. Even though using a range in place of a definite number may not significantly affect the United States’ deterrence calculations, it could produce a domestic political backlash. For instance, if the range’s upper boundary ever came too close to the treaty’s central limits, the public debate would most likely crystalize over such a high-end estimate and cast doubt about Russia’s compliance. This challenge is evident in the current debate about how many non-strategic nuclear warheads Russia has. Because these warheads are not limited and declared under a treaty, the US Intelligence Community uses a range of 1,000–2,000 warheads, of which the Pentagon uses the higher number, even though the Department of State says it includes retired warheads (US Department of State 2022, 11).

Under such a “gentleman’s agreement,” any previously existing protocols to facilitate dispute resolution between the state parties would no longer be formally in effect. The Bilateral Consultative Commission (BCC)—the joint body authorized to resolve compliance questions, make technical changes to the treaty’s protocol and annexes as new weapons are deployed, and mediate other treaty-related disputes—would be officially defunct upon New START’s expiration. As a result, if one party accused the other of materially breaching the agreement, there would be no formal mechanism for mediating and resolving that dispute. This challenge could be mitigated by the establishment of a new mechanism that mirrors the current role of the BCC.

In effect, continuing to adhere to New START’s core provisions would be an informal way of extending the treaty’s benefits. While this informality would certainly create challenges, the tacit knowledge and practices learned through 15 years of successful New START implementation could help transition both parties into such a new framework. While this option may not be sustainable in the long term, it could be considered a short-term bridge between New START and a follow-on agreement. This could prove particularly useful in the interim period if a mutual political commitment to the treaty remains, but time runs out before a new agreement can be concluded.

*************

Another obstacle to a non-legally binding handshake agreement is Russia’s historical insistence on having formally ratified treaties. For instance, Gottemoeller explained that Russia previously rejected a non-legally-binding bridging agreement after START, as it was afraid this would take away the necessary pressure needed to eventually reach a ratified treaty with the United States (Gottemoeller 2022). Russia’s insistence on formally ratified treaties may also be motivated by its fear that a future US administration could easily pull out of a negotiated executive deal. It is not known how flexible Russia might be today given the diminished likelihood that a two-thirds majority of the US Senate will vote to ratify an arms control treaty with Russia, particularly in the context of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

Plan B: pursuing an executive agreement

Another option for the United States could be to conclude a follow-on (sole presidential or congressional) executive agreement that would not require the Senate’s advice and consent for ratification as an Article II treaty would, but would still be as legally binding. Today, more than 90 percent of the United States’ international agreements are executive agreements concluded by the president (Bradley and Goldsmith 2018, 1278). In the field of arms control, however, executive agreements are still largely unexplored.

A distinctive advantage of pursuing an executive agreement over an Article II treaty is that it would allow each country’s head of state to bypass the Senate’s advice and consent required for Article II treaty ratification. This would be particularly valuable for the United States given the high degree of political polarization and low likelihood of bipartisan Senate support.

The flip side of this advantage for the United States, however, is that bypassing Congress in this way could create political backlash for a president. Congress could potentially block funding for a president to implement an executive agreement with Russia or even hold other presidential priorities at risk.

Moreover, if such an executive agreement included anything that could be construed to be a “further arms reduction,” it could be challenged under the US Arms Control and Disarmament Act:

“No action shall be taken pursuant to this chapter or any other Act that would obligate the United States to reduce or limit the Armed Forces or armaments of the United States in a militarily significant manner, except pursuant to the treaty-making power of the President set forth in Article II, Section 2, Clause 2 of the Constitution or unless authorized by the enactment of further affirmative legislation by the Congress of the United States” (22 USC Ch. 35, Section 2573(b) 1961).

A sole-presidential executive agreement inherently has substantially less congressional buy-in than a treaty ratified with the advice and consent of the Senate. Similar to politically-binding agreements, such an executive agreement is likely to be associated directly with the president who concluded it and could therefore be subject to violation or withdrawal by a subsequent president wanting to distinguish themselves from their predecessor. The fate of the JCPOA between the United States and Iran—in this case a politically- and not legally-binding agreement—exemplifies this dynamic. In 2018, against the advice of nonproliferation experts and many of his own advisors, President Donald Trump violated the agreement mainly because of its association with his predecessor, President Barack Obama, who signed the deal in 2015. This can be contrasted with the fate of New START, which was also negotiated under the Obama administration but remained relatively insulated from President Trump’s pattern of withdrawing from treaties and agreements—partly because of New START’s continued bipartisan support within Congress, particularly from those who voted in favor of the treaty in 2010.

A more politically-sound and -sustainable solution might be a congressional executive agreement that would require a simple majority vote in both the Senate and House.

Plan A: negotiating an Article II follow-on treaty

The ideal option for maintaining transparency, predictability, and mutual limitations of US and Russian nuclear arsenals would be the conclusion of a follow-on treaty to replace New START. That is also the least feasible option, especially as bilateral talks have been placed on hold since Russia invaded Ukraine. Nonetheless, a thorough consideration of each country’s respective arms control priorities could yield some opportunities for common ground when negotiations eventually resume.

In June 2022, Assistant Secretary of State for Arms Control, Verification and Compliance, Mallory Stewart, described the United States’ current arms control priorities vis-à-vis Russia as follows: “We want to sustain limits beyond 2026 on the Russian systems covered under new START; we want to limit the new kinds of nuclear systems Russia is developing; and we want to address all Russian nuclear weapons, including theater-range weapons” (Stewart 2022).

Priority one: maintaining strategic limits after New START

The United States’ first priority—sustaining mutual limitations beyond 2026—is likely to be shared by Russia. Both countries are aware of each other’s significant strategic upload capacities upon New START’s expiration, such that each country could more than double their total deployed strategic war- heads in the absence of existing limitations (see “The arms race in high gear” section). However, neither side appears to have the political appetite or economic capacity to engage in a strategic arms buildup.

Russia’s significant interest in preserving the bilateral arms control regime was on full display in the months and weeks leading up to New START’s extension in 2021. As Andrey Baklitskiy wrote at the time for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace:

“Both chambers of parliament voted on the extension in just one day, and passed it unanimously. Such speed and consensus—last seen over the annexation of Crimea back in 2014—shows how important arms control is to the Russian leadership. [. . .] Recently, it has become fashionable in Russia’s expert circles to opine that traditional arms control is obsolete as a concept, and doesn’t correspond to the reality of the modern world. This view partly stems from the fact that existing treaties have disappeared one after the other, while Moscow has not held talks on a new one for more than a decade. The energy the Russian state has put into supporting arms control efforts, along with the first progress made on this front, could now put an end to that trend” (Baklitskiy 2021).

Priority two: addressing Russia’s “exotic” new nuclear systems

The United States’ second priority—limiting Russia’s newer nuclear systems—will pose a greater challenge than maintaining the existing limits beyond 2026, but not an insurmountable one. In March 2018, President Putin unveiled a suite of “exotic” new nuclear systems—including the RS-28 Sarmat ICBM, the Avangard hypersonic glide vehicle, the Burevestnik nuclear-powered cruise missile, the Kinzhal air-launched ballistic missile, and the Status-6 Poseidon nuclear torpedo—immediately prompting concerns from US lawmakers that these systems would not be covered by New START limitations (President of Russia 2018; Cotton 2019).

While some of these systems do pose arms control challenges, two of them—Sarmat and Avangard—appear to be covered by the treaty. The New START protocols have clear provisions for including “new types” of strategic ICBMs within the framework of the treaty, and given that Sarmat has already been tested and is scheduled to be deployed by the end of 2022, Russia will have already provided many of the requisite prototype notifications to the United States (Al Jazeera 2022). In a similar vein, the United States’ incoming LGM-35A Sentinel ICBM will also enter the treaty smoothly.

Additionally, Avangard is not a particularly complex case: the hypersonic glide vehicle is carried by treaty-accountable ICBMs and the system itself meets New START’s definition of a “re-entry vehicle” under the description “that part of the front section that can survive reentry through the dense layers of the Earth’s atmosphere and that is designed for delivering a weapon to a target or for testing such a delivery” (US Department of State 2010, 60(7)). As a result, any ICBMs deployed with the Avangard system are now counted toward the central limits for both launchers and warheads.

Both the United States and Russia seem to agree on how New START will consider these two systems. In 2019, Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security, Andrea Thompson, stated in congressional testimony that: “We assess at least two of them, the Sarmat heavy ICBM and Avangard hypersonic system would count as existing types and be subject to New START at the appropriate point in their development cycle” (Thompson 2019). Six months later, the deputy director of the Russian Foreign Ministry’s nonproliferation and arms control department, Vladimir Leontiev, stated at the Valdai Discussion Club:

“As far as new Russian systems are concerned, the situation is dual. There are two systems that clearly fall under the treaty. First, the Sarmat, which can be easily included in the treaty as a new type ICBM (inter-continental ballistic missile), for which there is a special procedure, from the creation of a prototype to its authorization for service. [. . .] There are no big problems with Avangard, either, because it is an optional warhead for an ICBM of the corresponding type, to which the treaty applies, too. [. . .] The Avangard will enter the Treaty very smoothly” (TASS 2019).

The statuses of the three other new Russian delivery systems—Burevestnik, Poseidon, and Kinzhal—are less obvious. Neither Burevestnik nor Poseidon are likely to be deployed before New START’s expiration in February 2026; however, it is worth examining whether any of these would fall under the treaty’s existing counting rules, given that these could form the basis for a potential follow-on agreement.

Article V of New START stipulates that: “When a Party believes that a new kind of strategic offensive arm is emerging, that Party shall have the right to raise the question of such a strategic offensive arm for consideration in the Bilateral Consultative Commission.” The treaty’s supplementary protocol specifies what constitutes a “new” kind of strategic offensive weapon:

“The term ‘new type’ means, for ICBMs or SLBMs, a type of ICBM or a type of SLBM, the technical characteristics of which differ from the technical characteristics of an ICBM or SLBM, respectively, of each type declared previously in at least one of the following respects: (a) Number of stages. (b) Type of propellant of any stage. (c) Either the length of the assembled missile without front section or the length of the first stage, by more than three percent. (d) Diameter of the first stage, by more than three percent” (US Department of State 2010, 46(42)).

It is unclear whether this definition applies to any of Burevestnik, Poseidon, or Kinzhal, given that none could be considered ICBMs or SLBMs. Burevestnik is a cruise missile, Poseidon is a type of underwater torpedo, and Kinzhal is an air-launched ballistic missile. Moreover, at least two of these systems do not travel on ballistic trajectories, placing them outside the treaty’s definition of either an “intercontinental ballistic missile” or a “submarine-launched ballistic missile,” regardless of their launch systems or strategic roles in Russia’s nuclear arsenal.

However, in 2019, then-Under Secretary Thompson added during her congressional testimony that all three “meet the US criteria for what constitutes a ‘new kind of strategic offensive arms’ for purposes of New START” (Thompson 2019).

This interpretation is not likely to be shared by Russia. In December 2018, Russian officials sent a notice to the United States stating that they “find it inappropriate to characterize new weapons being developed by Russia that do not use ballistic trajectories of flight moving to a target as ‘potential new kinds of Russian strategic offensive arms.’ The arms presented by the President of the Russian Federation on March 1, 2018, have nothing to do with the strategic offensive arms categories covered by the Treaty” (Russian Federation 2018).

In its notice, Russia asserted that because none of the Burevestnik, Poseidon, and Kinzhal delivery systems are ICBMs, SLBMs, or heavy bombers, they fall outside the scope of the treaty. The statement also noted that “the Russian approach to the issue of criteria for defining new kinds of strategic offensive arms for the purposes of this Treaty is being worked at. The Russian Side is open for dialogue on this topic although it does not consider it as a priority taking into account pressing issues of the Treaty implementation discussed currently in the Bilateral Consultative Commission” (Russian Federation 2018).

The complex case for counting Kinzhal under the treaty framework depends entirely upon whether its carrier aircraft fits the treaty definition of an accountable “heavy bomber.” The treaty’s protocol states that an aircraft counts as a “heavy bomber” if it either (a) has a combat (meaning unrefueled) range of more than 8,000 kilometers (4,970 miles) or (b) is equipped for nuclear air-launched cruise missiles with a range exceeding 600 kilometers (370 miles) (US Department of State 2010, 23(80)). Given that Kinzhal is an air-launched ballistic missile, it does not satisfy the latter criterion. However, depending on how Russia intends to deploy the system, it could satisfy the former criterion.

Russia deploys Kinzhal on its specially-modified MiG-31IK Foxhound aircraft and has used the system in combat at least three times during its invasion of Ukraine (Kristensen and Korda 2022a; TASS 2022). The MiG-31IK’s combat range is estimated to be approximately 1,250 kilometers (770 miles)—significantly below the 8,000-kilometer threshold (Federation of American Scientists 2000a). As Pranay Vaddi, now Special Assistant to the US President and Senior Director for Arms Control and Nonproliferation, wrote in 2019 for Lawfare: “In this case, Kinzhal would not be accountable under New START, and neither should it be. Because the MiG-31 has a very limited range, it is not, even when armed with Kinzhal, the kind of strategic weapon that New START was intended to limit. Rather, if Kinzhal is deployed on a MiG-31, it will likely fill a limited, theater-strike role” (Vaddi 2019).

However, news reports have indicated that Russia may also deploy Kinzhal on its longer-range Tu-22M3M Backfire bombers (TASS 2018; RIA Novosti 2018). The upgraded Tu-22M3Ms are currently not classified as “heavy bombers” under New START because they are estimated to have a combat range of approximately 7,000 kilometers (4,350 miles), which—if correct—remains below the 8,000-kilometer (4,971 miles) threshold (Federation of American Scientists 2000b). The United States raised concerns about the upgraded Tu-22M3M system to Russia in September 2018, to which Russia responded as follows:

“The Russian side indeed plans to carry out modernization of Tu-22M3 bomber to the modification Tu-22M3M. This modernization will prolong the service life of the aircraft, as well as improve its systems of maneuverability, navigation and use of air weapon systems. At the same time, the range of the bomber will be below 8000 km, and it will not be equipped for nuclear [air-launched cruise missiles] with range exceeding 600 km. Proceeding from the aforementioned facts, the technical characteristics of the Tu-22M3M aircraft in accordance with paragraph 23 (80) of Part One of the Protocol to the New START Treaty do not allow to classify it as a ‘heavy bomber’ and it will not fall under the limitations of the New START Treaty” (Russian Federation 2018).

While the combat range of the upgraded Tu-22M3M may remain below 8,000 kilometers, it appears that the modernized aircraft will likely have probes to facilitate mid-air refueling (Interfax 2018). This is a significant alteration of the aircraft that will allow it to potentially reach intercontinental ranges. For this reason, these probes had been previously removed from Russia’s Tu-22M aircraft under the SALT II process, and the Soviet Union had made a politically binding declaration on July 31, 1991, that “it will not give the Tu-22M airplane the capability of operating at intercontinental distances in any manner, including by in-flight refueling” (Vance 1979; US Department of State 1991). However, this long-standing policy appears to now have been reversed, with defense sources telling Interfax in 2018 that: “The new refueling equipment will significantly increase Tu-22M3M’s combat radius and range of operation. The range will be comparable with one of strategic bombers” (Interfax 2018).

While this may not technically trigger the reclassification of the Kinzhal/Tu-22M3M combination as a treaty-accountable “heavy bomber” given that the aircraft’s unrefueled range is still likely to remain below the 8,000-kilometer threshold, the de facto transformation of a medium-range aircraft into an intercontinental-range aircraft could be enough for the United States to raise the matter at the BCC or in other bilateral forums. Moreover, in the context of negotiating a follow-on treaty, the United States could seek to close this potential loophole by addressing the fact that mid-flight refueling capabilities could theoretically turn a tactical bomber into a strategic one.

Priority three: addressing all Russian nuclear weapons

The United States’ third priority—limiting all of Russia’s nuclear weapons—likely poses the greatest challenge given the difficulty of verification and existing force asymmetry.

The United States is likely aware of the challenge, thus phrasing its goal to “address all Russian nuclear weapons” rather broadly. This could, for a start, be achieved through unverified data exchanges. Nonetheless, any negotiations that concern non-strategic nuclear warheads will be complicated by the asymmetry of Russia having up to 10 times more non-strategic nuclear warheads than the United States (1,912 compared to 200) (Kristensen and Korda 2022a, 2022b). Were Russia willing to include non-strategic nuclear weapons in a treaty, it would likely ask for US concessions in another area, although it has not specified so far what this might be. The Russian government did state, however, that a precondition for discussing non-strategic nuclear weapons is that the United States withdraws such weapons from Europe (Berestovaya 2021). Other areas of asymmetry Russia could try to pull into a negotiation package might concern US missile defenses and conventional weapons.

Exacerbated by existing political tensions and the current arms control deadlock between the two countries, this issue is not likely to be resolved anytime soon. Rather, an effort to include non-strategic nuclear weapons in an arms control treaty could require several years of negotiations and confidence-building—possibly spanning multiple presidential administrations.

Lessons learned and next steps

To address the challenges of building a follow-on framework, we now look at the lessons learned from previous arms control negotiations and identify strategies the United States might follow to eventually achieve a successful outcome.

Clarify national security interests and identify corresponding arms control tools

It is common wisdom that arms control is not an end in itself, but is instead a means to ensure national security. In this view, any future arms control negotiations need to be preceded by a thorough reevaluation of the national security interests they are meant to achieve. During the Cold War, arms control worked in tandem with deterrence and other elements of national power to manage strategic competition. When the Cold War ended, the role of arms control changed to a collaborative tool to manage, first, a controlled drawdown of excess strategic forces, then, deep cuts of nuclear forces, and eventually, elimination. With the pendulum swinging back to strategic competition, arms control may once again have to serve principally as a tool to manage strategic competition. It is therefore important to address expectations about what arms control can tangibly achieve in the coming years.

As noted above, US officials and leading nuclear scholars have repeatedly listed the following as problems that arms control should address: the loss of transparency with Russia, China’s buildup, new weapons, risks of inadvertent or accidental escalation, and the deterioration of international norms. This section explores how the United States should prioritize these issues given the return to strategic competition, and which arms control tools it should rely on for each.

First, with the war in Ukraine and the generally growing risk of regional conflicts involving China or Russia, the United States’ most pressing interest should be to minimize the risks of inadvertent or accidental escalation. The United States’ time would likely not be wasted here as ensuring “nonevents” constitutes “a strong mutual interest among the United States, Russia, and China” (Talmadge 2022). Besides addressing the root cause by cooperating to reduce regional tensions, nuclear experts and US-Russia military-to-military dialogues have emphasized a series of measures to help prevent escalation and eventual nuclear use: (1) maintain communication lines; (2) hold consultations on military operations and doctrine (to include provisions that would prevent escalation and rule out the first nuclear strike); (3) increase regular contacts between the two militaries (expanded to mid-level and regional commanders), including detailed notifications about intentions, threat perceptions, and potentially ambiguous exercises and operations; and (4) observe each other’s military exercises (Woolf 2021; Chalikyan 2021). Given Putin’s escalatory language regarding Ukraine, these measures—which luckily do not require a formal treaty—cannot wait any further. In the short term, they would complement New START. In the intermediate term, they would provide some limited, but much-needed confidence should there be no immediate follow-on treaty. In the longer term, risk reduction efforts may “create opportunities for the parties to address and resolve those security concerns that are blocking the path to nuclear disarmament” (Woolf 2021).

Second, the United States should prioritize preventing the loss of transparency regarding Russian strategic nuclear weapons as these continue to comprise most nuclear weapons that can reach the US homeland. In the medium-term, these are still owned by Russia, not China. New START’s verification and monitoring regime continues to be a highly suitable tool in this regard, because it allows the United States to track the numbers, types, sizes, locations, readiness, and movements of these weapons. This information helps avoid misunderstandings and worst-case planning assumptions that would otherwise fuel a new arms race. It would therefore be in the United States’ best interest to continue a similar mutual verification and monitoring regime of offensive strategic nuclear forces. For non-strategic nuclear weapons, data declarations would likely be the most suitable transparency tool to address the United States’ concerns for now. Issues surrounding intrusiveness and feasibility make a fully verifiable framework for these weapons rather difficult absent the necessary political will.

Third, given the US bipartisan concern with Russian treaty violations and the resulting deterioration of international norms, it is within US’ interest to revitalize the latter. The value of any future arms control treaty or agreement diminishes if it becomes common practice to simply violate them or exit them on a whim. Therefore, to ensure that arms control negotiations are worth the effort and that their value does not disappear overnight, it will be essential to revive international norms surrounding nonproliferation. This could be achieved through bilateral and multilateral normative statements, use of doctrine and strategy dialogues, as well as various tools to increase exit costs—including treaty provisions and allied, or ideally multilateral, commitments to sanction noncompliant parties.

Finally, how do the traditional tools of arms control—limitations and reductions—hold up today? Deep numerical reductions are unlikely without Russian and Chinese participation, given the level of prior reductions, expectations of cheating, and especially the new geopolitical order with China’s growing military power and nuclear arsenal. However, all three countries need to do their best to overcome these forces as soon as possible and fulfill their disarmament obligations under the NPT. Regarding non-strategic nuclear weapons that—unlike strategic weapons—do not pose a direct threat to each country’s homeland, reductions would not solve the most pressing concern: escalation through first use in a regional, conventional conflict (such as in Ukraine). Any remaining nuclear warheads could still be used first and risk escalation. For this reason, it is important to realize that reductions themselves should be a longer-term interest, and need to be complemented by other arms control tools such as the ones mentioned earlier. More immediate concerns regarding non-strategic nuclear weapons would be better addressed through risk reduction tools, transparency measures, and the strengthening of international norms.

Despite the limitations of traditional arms control tools, however, the United States (and Russia) would continue to benefit from the force predictability if limits on launchers and warheads remained. Opponents of arms control have for a long time tried to argue that these limits lead to decreased deterrence because it makes the United States reduce its nuclear forces while Russia keeps proportionally investing more into modernizing theirs (Trachtenberg 2021, 7). But changes in deterrence are largely the result of countries having different military doctrines rather than the treaties’ provisions. For instance, Russia relies more on its nuclear arsenal given its conventional forces’ inferiority. Today, given the ongoing modernization of the US nuclear triad and its higher number of strategic launchers and larger inventory of strategic nuclear warheads, the United States should feel confident that its deterrent will be preserved in respect to Russia under continued limits on launchers and warheads.

The key challenge is how China’s growing nuclear arsenal will affect these numerical and qualitative assessments of the US-Russian balance. Is the credibility of the US nuclear deterrent reduced because of China’s buildup? Will it undermine the US-Russian balance? If the United States increases its nuclear arsenal, will that cause either Russia or China to increase theirs even more? “The challenge will then be to redress Russia’s and China’s worst-case assessments that the capabilities the United States deploys to deter both countries could or would be used to defeat either one of them. If new approaches to arms control cannot be invented, the world is likely to see worsening security dilemmas, arms racing, and instability” (Dalton et al. 2022, 13).

Beyond that, future negotiators will likely want to focus on issues other than simple numerical reductions of launchers and warheads, such as the asymmetry in the nuclear production complexes—the roots of the nuclear warhead tree (Albertson 2022, 66). China, concerned about the survivability of its nuclear forces, may be reluctant to agree to fissile material production cut-offs. Because these concerns are partially driven by US missile defenses, it might, however, be open to combining this issue with a moratorium on the deployment of space-based missile defenses, the most plausible means for the United States to undermine China’s nuclear deterrent (Acton, MacDonald, and Vaddi 2021, 51–52).

Build arms control expertise

To have any chance at preventing the loss of strategic arms control’s benefits and develop remedies to safeguard strategic stability, the US government will need to make significant, long-term investments into rebuilding the relevant expertise.

One important factor that contributed to the arms control achievements in the mid-1980s to 1990s was the amount of expertise in the executive and legislative branches. Those who lived through the Cold War were naturally more concerned with, and educated on, nuclear weapons issues. Moreover, Congress still took its role in foreign policy seriously, and the Senate engaged in arms control through the bipartisan Arms Control Observer Group. For instance, Senate members of this group were tasked to consult with and advise US arms control negotiating teams, and “to monitor and report to the Senate on the progress and development of negotiations” (Roth 2014).

Today, however, most of these arms control experts in the executive branch and Senate have retired or in other ways moved on. Current staff has not been able to benefit from the direct experience and on-the-job training of the negotiating, ratification, implementation, and verification processes. The New START Treaty negotiations were the last to benefit from the contributions of the remaining experts and champions from this era (Albertson 2021, 78). The Senate, while still somewhat engaged in the New START negotiations through the National Security Working Group, has largely lost the expertise from the days of the more-engaged Senate Arms Control Observer Group—due to increased partisanship, diminished prestige, and the GOP’s growing skepticism of legally binding international commitments (Roth 2014).

To regain the interest and expertise needed to think through today’s arms control issues, the US government should (1) make significant staffing, training, and retention investments; and (2) increase cooperation and exchange between Congress and the executive branch again. The latter could be achieved possibly through a revitalized congressionally-appointed liaison group as former Sen. Sam Nunn and former Secretary of Energy Ernest Moniz previously proposed (Nunn and Moniz 2017).

Although much of the deep technical expertise needed to develop effective arms control tools will require access to classified information, these efforts can, to some degree, be pursued in concert with civil society. External funding provided by foundations and philanthropic organizations has traditionally played an instrumental role in hiring, training, and empowering future generations of arms control experts. Many of these experts typically rotate through government at some point during their careers, and they rely on their external networks to both brainstorm new arms control ideas and build support for them in the public discourse. To that end, increased funding for civil society could play a pivotal role in fostering the deep bench of political and technical experts needed to pursue successful arms control negotiations in the future.

Demonstrate Presidential leadership

It is likely that the chances of any follow-up agreement will be closely related to the degree of presidential lea-dership, support, and involvement in the negotiations, even if such an agreement is ratified in Congress and is not an executive agreement. It is essential to articulate national security objectives at the highest level as soon as possible in the process. If leaders are engaged throughout, the rest of the government will set it as a priority (Gottemoeller 2021, 172).

Rose Gottemoeller, the US lead negotiator of New START, assesses that the greatest asset to the treaty’s negotiations was the willingness of both US President Barack Obama and Russia President Dmitry Medvedev to engage—and to use their knowledge about treaty issues. The opening of the New START formal negotiations can arguably be attributed to a US-Russian presidential joint statement that laid out the subject and scope of the new agreement. Two months after the first round of meetings, another presidential joint understanding that contained limit ranges likely enabled the negotiators to operate at a relatively quick pace.

Moreover, there was great and important progress when President Obama and President Medvedev agreed on final warhead and delivery vehicle limits during a side meeting at the 2009 Climate Summit in Copenhagen (Gottemoeller 2021, 46, 89, 91). Throughout these and other arms control negotiations, Russian negotiators have in the past been more likely to consider concrete proposals when they came from a presidential level.

Finally, given the Russians’ skills at slow-rolling, both presidents agreeing on the same timeline was vital to the relatively timely success of the New START negotiations.

Presidential backing, first, ignited the talks and, second, saved much time by allowing the negotiators to focus on the agreed-upon scope. In the context of a future follow-on agreement, it could be possible to negotiate a technical framework using interagency guidance before any public summit if the political environment is too challenging. It is clear that presidential leadership throughout the New START negotiations provided the delegations on both sides with the needed bureaucratic firepower to get things done quickly, and helped move negotiations along when they were seemingly stuck.

Understand the other side: Russia

On the Russian side, it is critical to understand the role that nuclear weapons play in their politics, military strategy, and—perhaps most importantly—its perception of itself as a nation (Williams 2016). Siegfried Hecker, former director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory, describes well the crucial role of such an understanding in a report describing his unprecedented visits to Russia’s nuclear complex in 1992:

“We quickly discovered that the Russian view of its nuclear enterprise could not have been more radically different than the prevailing American view. Our Russian colleagues and the nuclear ministry viewed their nuclear weapons and nuclear complex as the crowning achievement of Soviet times and essential to Russia’s political, scientific, and economic future. With Russia’s conventional forces having atrophied, nuclear weapons were viewed as their guarantor of sovereignty, assuring Moscow a seat at the international table. Nuclear materials were seen as an economic resource and a national treasure. Nuclear experts and their scientific institutions were seen as an engine for the recovery of the national economy” (Hecker 2017, 6).

In the 30 years since these visits, Russia’s view of its nuclear enterprise has not changed much, particularly considering the poor performance of its conventional forces in conflicts, epitomized by its current war against Ukraine. But perhaps surprisingly, this imbalance may be a boon for arms control given that Russia has typically viewed its participation in such negotiations as evidence of its “great power” status. Additionally, Russia may view a renewed arms control agreement as a pathway toward renegotiating the global geopolitical order on its own terms. As a result, Russia is likely to view arms control in a relatively positive light compared to other nuclear-armed states like China.

Although Russia is likely to be relatively amenable to the prospect of nuclear negotiations (as suggested by their quick extension of New START in 2021), they, like the United States, will not enter into agreements unless these serve their national security interests. Several key Russian security concerns may need to be addressed to ensure a successful follow-on agreement.

Chief among these concerns is the development of advanced US missile defenses. Russia has long regarded the limitation of anti-ballistic missiles as the “cornerstone of strategic stability,” and has often explicitly characterized missile defense limits as a precondition to strategic arms control. In 2000, President Vladimir Putin noted that “the mutual reduction of strategic attack weapons . . . is possible only when the ABM Treaty continues to hold” (Woolf 2002). Additionally, throughout the New START negotiations, Russian negotiators attempted on several occasions to bring the issue of missile defense to the table—particularly following pressure from Putin, for whom missile defense was a priority issue (Gottemoeller 2021, 97).

Given the advancements in US defensive capabilities and Putin being back in the presidential seat today, it is likely that Russia will continue pressing the issue of US missile defenses. As Russia has historically been highly effective at drawing out negotiations, they may initially insist again on US concessions in this area—but they should hopefully recognize that it would not be worth jeopardizing strategic offensive arms control over the issue.

If Russia refuses to yield, however, the United States could again offer to place some limits on its missile defenses as part of a negotiation. At present, the US missile defense architecture appears to be an ever-evolving, open-ended project—rather than a clearly-defined effort to reach specific deterrence objectives. This has been recently underscored by increasingly blurred lines between theater and homeland defenses, as well as President Trump’s assertion that US missile defense will continue to evolve to “detect and destroy any missile launched against the United States anywhere, anytime, anyplace” (Sonne 2019). These factors likely validate the concerns of Russian strategists who largely never believed previous US assurances about the limited nature of their defenses (Woolf 2002).

To that end, the United States could consider establishing clear goals and limitations for its missile defense architecture, clearly communicate them to Russia, and then assess which constraints would be acceptable to unblock the path toward strategic arms control. Such constraints would not necessarily have to affect existing US capabilities but could involve placing a cap on interceptors at a higher level than what is currently deployed (Arbatov 2021). Given China’s similar concerns about US defenses, such actions could potentially also help bring China to the negotiating table.

Finally, regarding one of the United States’ core concerns—nonstrategic nuclear weapons—Russia has so far repeatedly posed preconditions to even begin talks that have been perceived as a pretext to avoid negotiations: the removal of US nuclear weapons from Europe and the elimination of NATO’s nuclear-sharing arrangements and related infrastructure. While the Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons posture has been transitioning to a combination of assets in support of specific missions, the Russian military, political leadership, and elites still believe that Russia needs a larger non-strategic nuclear weapons force than does NATO. This is primarily because Russia sees its non-strategic nuclear weapons to some extent as compensation for the larger US strategic nuclear arsenal.

Because Russia is unlikely to agree to equal ceiling and intrusive verification measures, a phased approach starting with transparency measures would be more promising. However, Russia might be susceptible to an effort to put its 2020 political commitment to freeze its nuclear stockpile back on the table (Pomper et al. 2022, 46–47). In the longer term, to overcome Russia’s perceived need to compensate for having less strategic nuclear weapons, actual reductions might need to wait for future negotiations including the United Kingdom, France, and China (against whom Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons could be used in a strategic way).

Understand the other side: China

The Chinese side is more difficult to understand. First, China has never engaged in nuclear arms control talks with the United States—unlike Russia, with which the United States has half a century of experience. Second, while China formally maintains a no-first-use policy, doctrinal debates are still ongoing about the limits of this policy (Leveringhaus 2022). To make matters worse, the security concerns related to the two country’s growing competition have restricted opportunities for US-Chinese academic exchanges that would allow the United States to better understand China’s goals and doctrine (Zhao 2021).

What seems clear, however, is that it would be almost impossible to include China in an immediate follow-on treaty to New START. First, the remaining time until February 2026 is not enough to include an entirely new negotiating partner with whom no such negotiating history or relations exist. Notably, it took the United States and Russia decades to get to their first verifiable arms control treaty. Second, Chinese officials have explicitly and repeatedly rejected joining arms limitation talks and previously suggested that they will join such negotiations only after the “huge gap” between their arsenal and the US and Russian nuclear arsenals has been closed. Until then, however, they have signaled that they stand ready to discuss “all issues related to strategic stability and nuclear risk reduction in the framework of P5, [the UN Security Council’s five permanent members, including] China, Russia, US, UK, and France” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China 2020).

China likely perceives time to be on its side and is probably waiting until it gains the needed leverage to become a more equal negotiating partner in this area. The projected increase in the size of the Chinese nuclear arsenal—perhaps with up to 1,000 warheads by 2030 (US Department of Defense 2021, 90) and potentially as many ICBMs as each of the United States and Russia—could potentially create new opportunities for arms control discussions around the end of this decade. But, even then, China is unlikely to agree to strategic arms control limits until it feels confident enough in its nuclear forces’ continued survivability. Moreover, China has traditionally relied on secrecy and opacity to help safeguard its smaller nuclear arsenal (Riqiang 2016). It would have to accept some degree of transparency to join a verifiable arms control regime like the New START treaty.

Meanwhile, to make any progress, the United States should continue to explore the following questions: What are the lessons from previous nuclear dialogues with China that may form the basis for future joint efforts? A previous track 1.5 dialogue (a term of art to describe situations in which both official and non-official actors cooperate) with China clarified that China, seeking recognition for its prominent role in the new international order, is interested in discussing a “new paradigm of strategic stability—one not built around deterrent threats, especially nuclear blackmail—but broader ideals of cooperation and ‘mutual respect’ ” (Santoro and Gromoll 2020, 11). The United States needs to therefore think about possible ways to make China feel this interest is being addressed while preserving its national security priorities.

Moreover, China’s strategic stability concerns all center around the fear that the United States might be after “absolute security,” looking to overcome mutual vulnerability. Therefore, the current and future US administrations should consider tools to build confidence in this area with China. Even if informal and on a track 1.5 basis, these could eventually lay the groundwork for a first treaty with China.

To lay the groundwork for cooperation with China, the United States should also explore the following questions: Is there any room for the United States and China to slowly start exchanging certain types of information about each other’s strategic nuclear forces, in particular those types about which China might not feel as protective? What would the United States be prepared to offer China in exchange for limits on Chinese nuclear forces? Is a more creative French-style approach to negotiations needed—that offers to combine unrelated issues, which in China’s case would include tariffs, special economic zones, and other economic issues? How can the United States best leverage the P5 forum for risk reduction with China?

Make long-term investments

Because of the difficulty of achieving the United States’ current objectives, especially the inclusion of China, in a follow-on treaty, it is advisable to develop and pursue a long-term strategy for achieving these goals. Given the current geopolitical context, a treaty covering Chinese strategic nuclear forces might not happen until the 2030s when China feels secure enough in its nuclear deterrent capability and negotiation leverage.