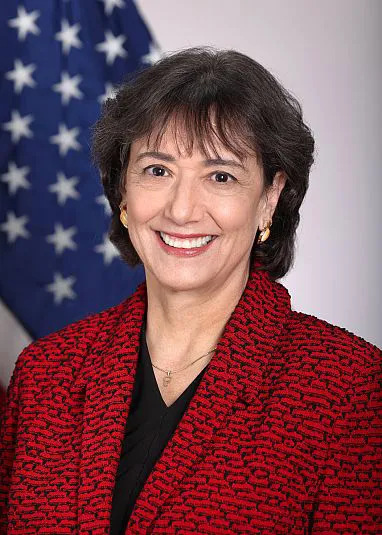

The impact of DOGE’s funding cuts on biomedical research, from the point of view of former NIH director Monica Bertagnolli

By Dan Drollette Jr | May 13, 2025

The impact of DOGE’s funding cuts on biomedical research, from the point of view of former NIH director Monica Bertagnolli

By Dan Drollette Jr | May 13, 2025

In the world of biomedical research, one institution towers over the rest—the National Institutes of Health, or NIH.

It can be argued that it’s largely because of this 138-year-old government agency—a part of the US Department of Health and Human Services—that the human genetic code was deciphered, AIDS was isolated, hepatitis C discovered, and where the basic research that lead to the COVID-19 vaccines was done. At least 171 scientists who have received Nobel Prizes have either conducted research at the NIH or been supported by NIH funding; the NIH pays the bills for the large clinical trials in heart disease, diabetes, cancer, chronic diseases, and many other fields that inform so much of health care today.

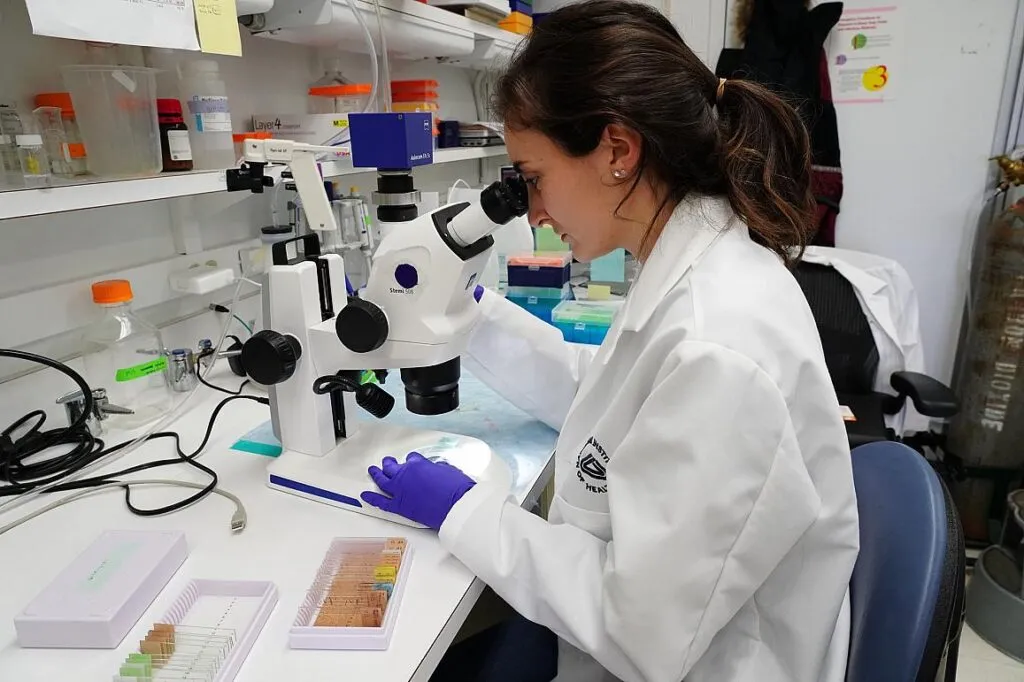

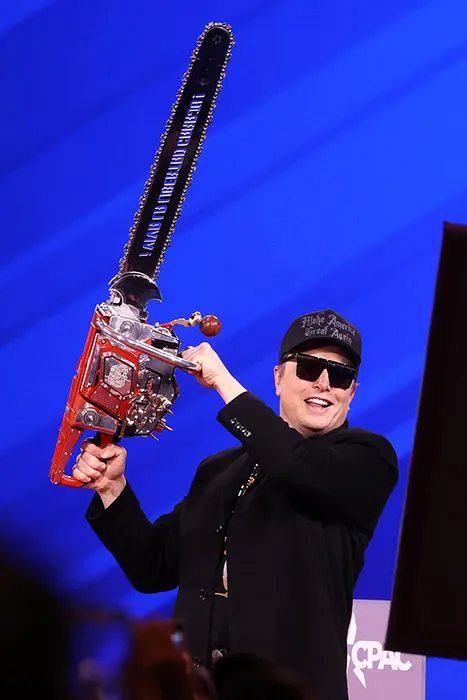

But the NIH is now facing cuts of 35 percent, requested by billionaire Elon Musk’s so-called Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE).[1] Consequently, researchers have had to struggle with getting reimbursed for routine expenses such as lab mice—especially after DOGE put a one-dollar spending limit on the use of government credit cards. Years of work have been put at risk.[2]

The gloom has been palpable among researchers. I’ve attended many annual meetings of the American Association for the Advancement of Science over the years, but 2025 was the first time I ever saw lectures and discussions with titles like “When Reliable Data Disappears” and “Addressing Researcher Harassment.”

So when I saw that there was an unscheduled, half-hour talk to be given at the last minute on the expo floor by Monica Bertagnolli—who had resigned from her post as director of the NIH just four weeks earlier[3]—I was eager to drop in, and get a sense of what was happening at the agency from the ultimate authoritative source.

But she doesn’t define herself as exclusively an administrative head: Before leading the $47 billion agency, Bertagnolli ran her own research lab for years, worked as a cancer surgeon—and was herself a survivor of breast cancer.

We chatted after she stepped down from the podium, and Bertagnolli agreed to this remote interview, which was conducted several weeks later, on March 31.

(Editor’s note: This interview has been condensed and edited for brevity and clarity.)

Dan Drollette Jr.: What does the NIH [National Institutes of Health] do?

Monica Bertagnolli: The NIH’s goal is to conduct the broadest possible range of research that can deliver health for all people. It does this a number of ways, such as by funding effective therapies or preventive approaches to disease and health. It also funds behavioral research, because human behavior plays a great role in health, and we need to understand that behavior.

The reason for this is that while our health is dictated to a certain degree by the genes we inherit, to a much bigger degree it’s determined by what we encounter after we’re born—our environment, our diet, our social interactions. All of those play a role in health. So we also do research concerning those factors.

And we also do health systems research: In other words, how can we deliver better care to keep people healthy?

Dan Drollette Jr.: Is it fair to say that support for the NIH was traditionally pretty bipartisan?

Bertagnolli: Very bipartisan. We’d always been very fortunate there.

Drollette: Though it seems that things have sort of changed lately, with all the funding cuts and layoffs going on.[4]

How many people does the NIH employ?

Bertagnolli: I don’t think that the number that the NIH itself employs is the best way to look at it, because 83 percent of NIH funds are directed outside the organization itself, to fund researchers in academic institutions, companies, states—many different places.

That means that 83 percent of its approximately $47 billion budget—at least 83 percent as of 2024, when I was at the helm—goes outside the NIH.

The NIH puts out calls for research proposals, vets them, and funds the most meritorious. And that’s where the money goes—out to researchers to conduct the research.

It does have a modest amount of its budget—roughly between 10 to 12 percent—that it uses to run its own research programs, including the NIH Clinical Center, which is the only hospital in the United States devoted entirely to biomedical research, and where a lot of proof of concept studies are done.

The rest is for administration and management of a research portfolio that in a single year funds between 50,000 and 60,000 grants, for over 300,000 investigators and 2,500 different institutions across the nation. It funds, monitors, and manages those programs for the US government.

Drollette: For some of those institutions, it must be pretty devastating when they can no longer rely on getting funding from the NIH for the kind of monies that allow for their personnel, their maintenance—their everyday things.

Bertagnolli: Again, not the right way to look at it.

The way it works is this: When someone applies for funding from the NIH, their funding proposal lists the things that individual person specifically will require to do their work. It’s things like paying their researchers’ salaries and their supplies and their basic software and equipment—but they do not submit as part of their proposal any of their overhead costs, such as their utilities, their building [maintenance], or the expenses of their research oversight committees or their institutional review boards. They do not apply for those things in the award.

But of course, they can’t do their work without these things—what are called “F and A” [Facilities and Administrative] costs, or sometimes referred to as “indirect costs.” It’s an unfortunate term because what it really refers to are all the other things they absolutely require in order to do the work.[5]

Up until now, a portion of these [indirect costs] were also covered by the NIH at a rate that was individualized to the type of research and to the institution where the research is being done. So there might be, for example, a higher overhead rate at a place that was in the middle of a major metropolitan area—just like for any company. Or for a type of research that requires really expensive equipment, because equipment costs are not necessarily part of the budget.

Or they might also have a lower rate, if it’s for something that’s basically someone sitting at a desk doing research on a computer.

So anyway, that’s what that is.

And it is a mistake to say: “Oh, we’re funding all these institutions.” No, we’re funding institutions to do the work that is awarded in the grants. We’re not funding them to go build a building or fix the potholes in their parking lot. We’re funding them to do the work.

Drollette: But again, for some smaller institutions, these overhead costs—F and A costs—can be substantial. So it can really hurt if they can’t count on the federal agencies’ giving them some kind of funding regularly.

Bertagnolli: That’s a real problem for them. Big institution or small, it doesn’t matter.

For any researcher, any research department, any institution who wants to do research, it’s the same: If they don’t have that overhead support covered, then they have to find it from somewhere else. It’s all part of what it takes to be able to accomplish the research.

I do think that perhaps the bigger institutions are maybe somewhat sheltered because they might have bigger donors. But big or small, it’s still just about paying the rate it takes to do the research.

Drollette: It sounds like it was those F and A rates that the so-called “Department of Government Efficiency” was really targeting.

Bertagnolli: Well, that was one part. But they also flat-out eliminated a lot of grants.

So both things are happening at the same time.

They even cut established grants—grants that have been already funded and are already underway.

So, a steady stream of researchers, in the middle of work that they had been funded to do, are seeing that funding stopped.

Drollette: It’s pretty astonishing to me, as an outsider, to see that a grant that’s already in effect—money that’s already been promised in return for doing something—can suddenly be yanked. I thought a grant was like a contract: These two parties agreed to something, with Party A doing something in exchange for payment from Party B.

But I see you shaking your head…

Bertagnolli: It’s a grant. And the way the federal government works is that the NIH gets its funding year by year—so it’s got to live within its means for an entire year. And by the end of that year, the money is gone, and it has to get money for the next year.

This is true even when the NIH awards grants that are supposed to run for seven years, for example.

So, in order for that to be possible, the money needs to come in regularly, year after year. It’s not like they have seven years’ worth of funding sitting in a bank somewhere that they’ve reserved for that researcher and can dole it out. That’s not the way it happens. The funding comes year by year, once it’s approved by Congress.

Drollette: But once it’s been approved by Congress, I thought that was pretty much the end-all of it—a done deal. In other words, once Congress says “We’re giving X amount of money to the NIH this year,” then the NIH can spend it all for that year, as it sees fit—it’s not like the money can be clawed back by someone else, such as the executive branch, for example?

Bertagnolli: Well, the NIH budget just came in two weeks ago, under a continuing resolution setting the budget for fiscal year 2025. That just happened, and there was a $250 million reduction in overall NIH funding in that continuing resolution: so no new funding. And with inflation and everything else, its buying power has gone down.

But that’s supposed to be what money the NIH has available to spend between now and October 1, 2026.

However, as you know, we’re having a kind of national conversation about whether that money must be spent according to Congress. The question is whether that money is a ceiling or a floor.

Drollette: Okay, so that’s how the Trump administration is wording it.

Bertagnolli: That conversation is still going on. And you know, our members of Congress have—or believe they have—the power of the purse. When they say, “This is how much money we’ve allocated,” they expect the executive branch to spend it in good faith. And I think the executive branch is taking another approach, this time.

Drollette: You officially are no longer associated with the NIH, but you must still have your ear close to the ground. What I’m trying to get is a sense of …

Bertagnolli: No, quite the opposite. I’m a civilian like everybody else now. I have no special knowledge of what is going on. I have no inside track.

Drollette: Because I was just trying to get a sense of whether those cuts are going to hold.

Bertagnolli: I only know what everyone else knows—what the general public knows about the plans and strategies of the NIH or HHS [the US department of Health and Human Services].

I do think that we’re halfway through the fiscal year, and the things that have already happened—the grants that have already been canceled[6], the delays in funding that have occurred —mean that there will be a major reduction in productivity by NIH researchers this year, just because of what’s already happened. I think we can all be pretty confident of that.

Drollette: How do you think researchers and the general public should respond to these cuts? When we briefly chatted after you stepped down from the podium at that AAAS meeting, I think you said something to the effect that researchers have to be kind of like the Dory character in the movie “Finding Nemo” —just keep on swimming.

Bertagnolli: Yeah, just keep swimming.

By that, I mean that I want the young—the next generation [of researchers] to realize just how incredibly valuable, exciting, and important their work is, despite what is going on presently.

Biomedical research has really changed our world, making life better for so many people, just during the time of my career. And I want the next generation to remember that and not give up on it.

Because, frankly, with all the capabilities that we have at our fingertips today, this ought to be a tremendously exciting time for biomedical research.

Now, what this current reorganization and the funding challenges associated with it are going to mean, nobody knows—we just have to wait and see.

So, the message I really wanted to give is to just keep swimming. I really don’t want the next generation to give up on their commitment to this work—and frankly, that’s one of my biggest fears.

Because when you’re a young person looking for your first job, worried about how you’re going to raise a family and pay your bills, it’s really sobering to think about entering biomedical research during a time of such crisis.

But you know, I have faith that our society will see the value in what NIH research brings—as we have for so many years.

Drollette: That reminds me: I did an interview with someone just a few days ago for this issue of the magazine, who’s written a lot of books about medicine and disease over the centuries, and it was shocking to see how negative she was about what we have learned from events like COVID.[7] She was saying we’re going backwards—in danger of unraveling not only hundreds of years of progress in public health but also in the whole idea of science, fact, and the scientific method. The idea is that there seems to be an impetus to rule by feeling, or by general vibe, rather than by evidence. Do you think that’s overstating the case? Or what are your…

Bertagnolli: I think it’s very unfortunate that the value of science has been undermined by the rhetoric that we have seen.

It’s absolutely understandable that after something like COVID—which was terrifying—that everyone was shaken to the core. You know, so many terrible things happened with COVID.

But that somehow got translated into a mistrust of science—lashing out against, frankly, the very people who are trying their hardest to help. And lashing out against the principles that have brought so much benefit to people over decades.

Now, nobody’s ever perfect, and science is never perfect. But the methods and approaches of science are designed to deliver solid benefit to people.

While I believe it’s perfectly fine to challenge science and to demand that it be the best it can possibly be, I don’t think it’s appropriate to undermine the ability of the entire process—that only produces fear.

And fear can really cause some very harmful effects.

Drollette: Give me an example.

Bertagnolli: One of the most difficult and troublesome is something that we see in medicine: The people who have the most distrust in science are also the segment of our society who seem to be doing the worst.

What that says to me is two things. First—we have to do better for that segment of society. You know, forget what they believe right now; we have to find ways within their belief system to do better for them. These people are experiencing some of the worst outcomes across the nation, and by doing better for them—by showing that science can actually help them be healthier and live longer—then we’re in their trust.

Second—you can’t demand trust of anybody, you have to earn it. And I think the particular people who have the lowest trust in science are the ones where we have to work the hardest.

Drollette: Do you think that science—public health in particular—sometimes has trouble promoting its successes? For instance, I was astonished by the fact that we got a vaccine for COVID within months instead of years or more. It really is amazing. And yet it feels like these new mRNA vaccines are just not really getting the credit they deserve.

Bertagnolli: Yeah. I mean, it’s complicated, right?

The whole issue of COVID was complicated, and there were so many reasons why it was—and still is—an incredibly difficult episode for us in this country. Some of it was misinformation, a lot of it was fear. A lot of it was that we didn’t know what to expect; this was a brand-new bug, and we didn’t know how it would pan out.

We didn’t know how infectious it was. We didn’t know the best way to prevent people from being infected. We didn’t know for sure that a vaccine would work.

There were so many things we didn’t know. And I just think that’s very difficult for the public to accept, especially when they are scared. When people are afraid, they want to hear, “Oh, we know exactly what to do, no problem.” But we didn’t. And that was just the situation we were all in.

And there’s still big parts of the COVID pandemic that are lingering. Long COVID remains a serious problem that we haven’t solved—though we’ve learned a lot, we’ve got a lot more to learn.

And this is just my personal opinion, but I feel that public health has been really underfunded in our society. Yes, you need the cutting-edge science—and guess what, we’ve got that. We’ve got the big cutting-edge, basic science on steroids, and that really delivered for us—it delivered a vaccine.

But what we didn’t have was the public health part, the outreach, the monitoring and tracking, the helping people to not be as afraid. That public health end is where we hadn’t been investing as much as we should have, and it would have helped a lot if that end had been more robust.

Drollette: An epidemiologist friend of mine says that when public health measures succeed, there’s nothing to show, there’s nothing eye-catching. Because no one got sick, no one died, and no businesses or schools closed.

Bertagnolli: Right, it’s hard to celebrate: Nothing happened.

Drollette: Before we sign off, I did a little looking around on the web prior to this interview, and I read your Wikipedia entry. I saw where you’re originally from Wyoming, a deeply red state. What happens when you go back home? How do you explain what you do at work? What do you say when people ask why they have to wear a mask? And that’s not to pick on Wyoming, I worked in Yellowstone for two summers and fell in love with the state.

Bertagnolli: Wyoming’s a wonderful state full of just amazing people. I love it and still do.

But I do think it’s no different from anywhere else.

Wherever I am, I say: “Here’s what I know, here’s what I do, here’s what we think the science is telling us, here’s what we think is the best thing to do to be safe. Everyone makes their own decisions, and I’ll tell you what I think I can give you.”

I think almost every physician I know is actually really good at this.

If you’re a physician, you’re constantly meeting people who have ideas very different from what you think might be the right thing to do. I’ve heard all kinds of things from people who have cancer: about why they think they got it, what they think they should do, and what role they think they should be playing in their life place. And hey, all good—you sit and you work with them.

Which is something you have to do, if you’re trying to help someone. You have got to work with who they are, where they come from, what they believe, and what they think. And you do your best to be very upfront and honest about both what you know and what you don’t know.

That has always worked for me, as a doctor, and it’s no different when you’re in a situation like COVID—you’re always going to find people who think things very different than the way you do. But if you’re trying to solve a problem together—like trying to help them with their health—then you’ve got to work together, human to human, so that you can establish a relationship where you’re going to learn from each other.

Because guess what? We can be the smartest doctors in the world, but there’s ignorance on our side, too, you know.

So you have to try to work on a common goal, of having somebody be healthy. There’s no quick fix; it’s ultimately about people—one of them caring about that person sitting across from them.

Drollette: For some reason, I had the impression that you were more of a researcher working purely in the lab, but it sounds like you’re really a physician.

Bertagnolli: I’ve done a little bit of everything. I was a lab researcher for about 20 years, and I still collaborate with partners in the lab. I haven’t had a lab of my own for a while now, as I transitioned to be more directly responsible for clinical trials in research and oncology for quite a while.

I do spend a lot of my time lately thinking about better ways to deliver health care, using data—because our world is now being transformed by the new use of data, and I spend a lot of time thinking about how we can better use our data resources to benefit people.

Drollette: Any last comments?

Bertagnolli: I’m an optimist. We’ll get through this. People need us; there is no question. So we just gotta keep swimming.

Endnotes

[1]See Science article of April 3, 2025, “NIH under orders to cancel $2.6 billion in contracts” at https://www.science.org/content/article/nih-under-orders-cancel-2-6-billion-contracts

[2]“DOGE’s $1 spending card limit touches everything from military research to trash pickup,” Washington Post, March 9, 2025 https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2025/03/09/doge-government-credit-card-limits/

[3] More can be found at the January 14, 2025 “Statement from Monica M. Bertagnolli, M.D., on ending her tenure as NIH director” at https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/who-we-are/nih-director/statements/statement-monica-m-bertagnolli-md-ending-her-tenure-nih-director

[4] See the April 1, 2025 Nature article “ ‘One of the darkest days’: NIH purges agency leadership amid mass layoffs” at https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-025-01016-z

[5] More information on this aspect of NIH funding—and what the cuts to it mean—can be found at the University of California’s “Myths vs. Facts: F&A Cuts” at https://ucop.edu/communications/_files/uc-nih-fa-myths-vs-facts_f2.pdf

[6] For more, see the March 6, 2025 Nature article “Exclusive: NIH to terminate hundreds of active research grants” at https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-025-00703-1

[7] See the interview in this issue of the Bulletin magazine “Sonia Shah on pandemics and pushback: Lessons from the COVID experience”

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: DOGE, Department of Government Efficiency, NIH, National Institutes of Health, biomedical research, covid

Topics: Special Topics