Hypersonic Missile

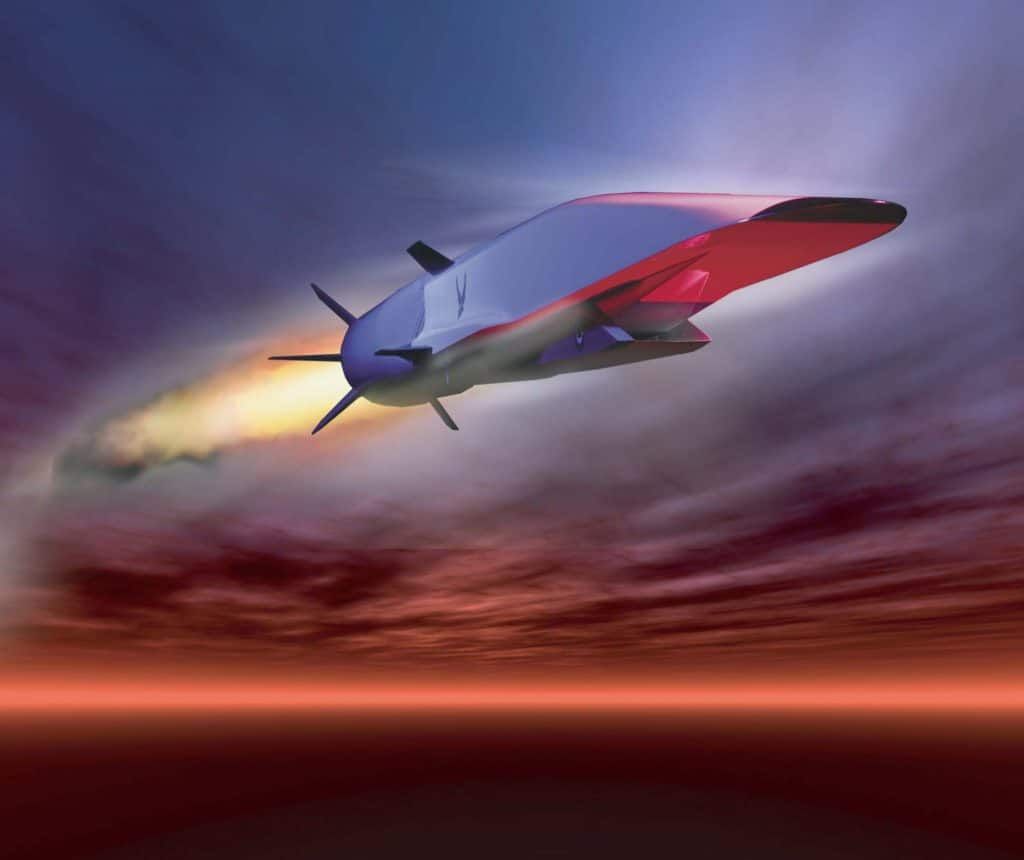

Credit: US Air Force graphic

Hypersonic missiles have the ability to maneuver during flight and travel faster than Mach 5 (five times the speed of sound, or approximately 3,800 miles per hour). Existing research and design efforts associated with hypersonic weapons have focused on two types of missile technologies.

The first, a boost-glide system, is designed so a glider sits on top of an existing intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) launched on a ballistic trajectory. At a designated level of “boost,” the warhead-containing glider is released and maneuvers to its target without additional propulsion.

The second type, perhaps more complex to develop and deploy, is a hypersonic cruise missile. This type of weapon involves a supersonic combustion ramjet or turboramjet engine that provides propulsion throughout its flight, and this feature would allow it to travel at significantly lower altitude than its boost-glide counterpart, complicating efforts to track it via radar.

In both cases, though the missiles are named for their speed, it is their potential maneuverability that represents the central challenge to existing strategic stability arrangements. After all, ordinary ballistic missiles also travel at hypersonic speeds as they re-enter the atmosphere.

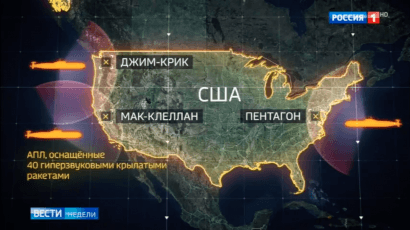

In his 2018, Russian President Vladimir Putin announced the development of a hypersonic glider that he claimed would be able to get through all US defenses. The following year, on December 24, Putin said that Russia had deployed its first nuclear-capable hypersonic missile: “Today, we have a unique situation in our new and recent history. [Other countries] are trying to catch up with us. Not a single country possesses hypersonic weapons, let alone continental-range hypersonic weapons.”

In January of 2019, the Congressional Research Service revealed details of the longstanding US research into hypersonic missiles

There have been several calls to implement a ban on testing hypersonic weapons.

Andrew W. Reddie, deputy director for the Nuclear Policy Working Group, wrote that a “hypersonic arms race” may increase “the risks of inadvertent escalation. The development and deployment of conventional hypersonic missile systems may also lead to a failure among parties in a conflict to discriminate between conventional and nuclear attacks.”

“Proponents of the US hypersonic program say that none of the missiles will ever carry nuclear warheads,” wrote Ivan Oelrich, a Senior Non-resident Fellow at the Council on Strategic Risks, in 2020. “This is hardly reassuring to Russia and China, of course, because no nuclear system would ever be tested with an actual nuclear warhead and, regardless of testing, there is no way for Russia and China to be sure one way or the other while the missile is in flight. If current air-breathing cruise missiles could be armed with either conventional or nuclear weapons, then so could hypersonic gliders.”

The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists publishes stories about nuclear risk, climate change, and disruptive technologies. The Bulletin also is the nonprofit behind the iconic Doomsday Clock.

Latest stories about hypersonic missiles