I was wrong; natural gas will dominate

By Kurt Zenz House | March 27, 2012

I was dead wrong.

In September 2009, I authored an essay for the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists in which I argued that the then recent divergence between oil prices and natural gas prices was temporary.

I was dead wrong.

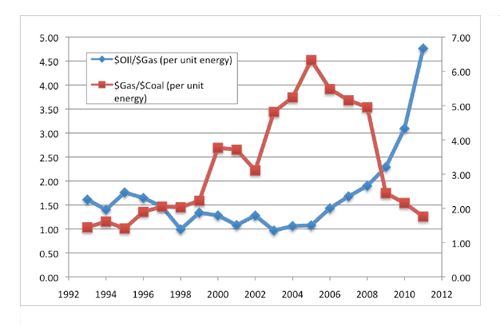

My argument was simple. Between 1990 and 2009, the average price of Brent Crude oil had been between 1.5 times higher than the average price of North American natural gas, on an energy-equivalent basis. Furthermore, that price ratio had been remarkably stable. During those 20 years, the price of oil varied from less than $11 per barrel to over $147 per barrel, yet the ratio of oil-to-natural-gas prices only varied from 1.1 to about 2. As the price of oil rose, in nominal terms, by a factor of 14, the oil-to-gas price ratio didn’t even double. Furthermore, the standard deviation of the annual price ratio was a mere 20 percent of its average value over those 20 years.

North American natural gas and oil prices were tightly linked, and the reason for that historic link was obvious.

Natural gas and oil can substitute for each other in many applications; both natural gas and oil are used in residential and commercial heating; fertilizers are manufactured from both fuels; petrochemicals, such as ethylene, and common plastics, such as polyvinyl chloride, are made from either natural gas or oil. Even liquid transportation fuels can be produced from both oil and gas, although the current global capacity of gas-to-liquids production is less than 40 million barrels per year.

Something strange, however, started to happen in late 2009 and early 2010. The price of both oil and natural gas plummeted after the financial crisis of 2008. In that year, the price of oil dropped from $147 per barrel in July to $35 per barrel by November, and natural gas followed oil down to the cellar. But, throughout 2009, the price of oil gradually rose, while the price of natural gas stayed near its November 2008 low. In 2010, the price ratio of oil to natural gas had risen from about 1.8 in 2008 to over 4 — double the previous record high!

Two phenomena were responsible for the rise of that price ratio. The first was that electricity demand throughout the United States decreased in 2009 by 4 percent. Since about a quarter of the natural gas consumed each year in the United States is consumed for power generation and less than 2 percent of oil is consumed for power generation, then a drop in electricity demand — all other things being held equal — will increase the oil-to-gas price ratio.

The second phenomenon was the rapid development of the North American shale gas reserves. In 2009, I argued that the North American shale gas reserves were real and that we should expect increases in domestic gas production as a result of the newly discovered resource. By my line of reasoning, the market would respond to the historically low cost of natural gas relative to oil by switching the input fuel used in every possible application from oil to natural gas. Further, I argued that the increased demand for natural gas would, eventually, pull the oil-to-gas price ratio down to its historic range.

Today, the oil-to-gas price ratio is an eye-popping 7.

The shale reserves are real, and large portions of them are cost-effective to develop at very modest gas prices. In five years, natural gas extracted from shale has grown from 5 percent of US gas production to nearly 25 percent, and its share of US production will only continue to grow. The shale reserves have outperformed even the most optimistic observers. In 2010, the projected future cost of a gigajoule of gas delivered in 2020 was about $8; today, the projected price is about $5.

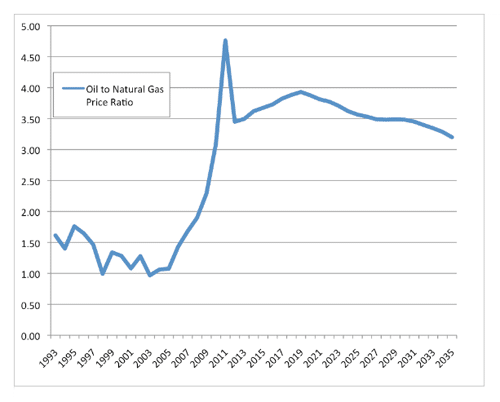

Has the oil-to-gas price ratio reached a new and stable plateau? The future markets certainly think so.

As shown above, the futures market is currently betting that the ratio will stabilize near 4. We are witnessing the recalibration of a resource.

Before the vast North American shale reservoirs were understood, the marginal cost of natural gas and oil extraction were sufficiently similar on an energy-equivalent basis that fuel-switching kept their relative prices stable.

The world has changed.

The overwhelming evidence that the marginal cost of North American natural gas production is substantially lower — on an energy-equivalent basis — than the marginal cost of global oil production, now has me convinced. There is not a global natural gas price because long-distance transport of natural gas is expensive and difficult, while oil is traded globally because transport is inexpensive and easy. As such, a 20 percent increase in North American gas production will affect North American prices, while a proportionally large increase in North American oil production would not.

The conclusion is unavoidable: Natural gas will dominate the evolution of the North American energy industry over the next 20 years, and there will be a boom in downstream natural gas investments. For example, the United States still imports 55 percent of its nitrogen fertilizer. In time, the United States might become a net exporter of fertilizer and related chemicals.

Similarly, investments will be made to enable natural gas to be used more in transportation. At current prices, running a car on compressed natural gas (CNG) costs the equivalent of $0.50 per gallon of gasoline, and the current payback time to convert a long-haul 18-wheeler from diesel to CNG is about one month. If markets are efficient, then we will see the rise of a commercial CNG fleet in North America.

But the future is hard to predict.

Hardly anybody predicted that the oil-to-gas price ratio would skyrocket like it has. In 2007, Goldman Sachs, Kohlberg Kravis Roberts & Co., and the Texas Pacific Group acquired TXU, a Texas utility. Since many of TXU’s coal-fired generating assets operate in unregulated markets, TXU was very exposed to a significant drop in natural gas prices because gas-fired power plants typical set the market price. As a result, those private firms made a $9 billion equity bet that natural gas prices would stay well above $6 per gigajoule for the long term. Currently, natural gas prices are less than half of that, and the credit insurance markets are betting that there is an 80 percent likelihood that TXU will default on its debt within five years; Warren Buffet is one of the lenders who likely will not get his loan repaid.

So, the future is hard to see. But it is unambiguous that the marginal cost of natural gas production in the United States is at historic lows relative to the marginal cost of global oil production, and as such, I am convinced that there is a price ceiling on North American natural gas production that is well below $6 per gigajoule.

Like I said, the world has changed: Over the next decade, natural gas will dominate US energy investments and US energy policy.

Editor’s note: This piece was written with the help of Michael Rieser, a senior project manager at C12 Energy.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Topics: Climate Change, Columnists