David Sanger on the perfect weapon

By Elisabeth Eaves | October 24, 2018

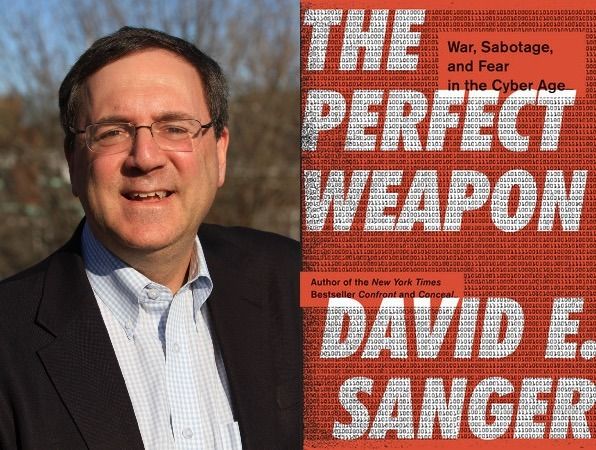

Photo of David Sanger by Stephanie Le.

Photo of David Sanger by Stephanie Le.

Even though major newspapers cover the thrust and parry of cyberwar, it can be difficult to grasp the bigger picture. After all, cyberweapons are new, shrouded in secrecy, and invisible to the untrained eye, making them harder to comprehend than bullets or bombs. But with governments fighting ongoing cyberwars, inflicting damage that has cost billions of dollars and undermined democracy, it is time for a much larger public conversation on the subject, as David Sanger insists in his new book The Perfect Weapon: War, Sabotage and Fear in the Cyber Age.

Sanger, the national security correspondent for the New York Times and a senior fellow at Harvard’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, has penned one of the most comprehensive and accessible histories of cyberwar to date. He begins with the first sophisticated state-on-state cyberattack, in which the United States and Israel used a computer worm dubbed Stuxnet, which they began developing in 2006, to shut down Iranian nuclear enrichment plants. He lays out events since then, up to and beyond the Russian hacking of the US Democratic National Committee a decade later, the repercussions of which are still being felt.

Sanger’s book is more than a history and primer. It also advances a series of arguments, among them that the United States is not ready for the kind of cyberattack likely to come, that the extreme degree of secrecy surrounding cyberweapons is excessive, and that the world needs to move ahead with setting some limits on cyberwarfare—perhaps a sort of “Digital Geneva Convention”—even if governments aren’t ready to do that yet.

Major cyberattacks have struck city services in Atlanta, the health-care system in Britain, centrifuges in Iran, a steel plant in Germany, a casino in Las Vegas, a petrochemical plant in Saudi Arabia, and missile systems in North Korea. In other words, Sanger writes, “The early damage has been limited.” But it will expand and accelerate, he believes, with virtually no chance that the hyperconnected and therefore target-rich Western democratic world will escape unscathed.

Sanger spoke to the Bulletin about all this and more by telephone in August. He was at his house in Vermont, on the edge of the Green Mountain National Forest, where that morning he had spied a black bear. This interview has been edited and condensed.

BAS: Could you briefly explain what implants are and why they matter?

DS: An implant is nothing more than malware that is hiding in a system. It could be in the utility grid. It could be in utility companies’ control rooms, as the US Department of Homeland Security recently warned some Russian malware was. But that’s not the only place an implant can be. It can be in your personal computer watching for something, looking to record your credit card numbers when you type them in. It could be inside your cell phone monitoring not only conversations but text. It could be in an industrial control system.

It was through implants that the United States got malware into Iran’s nuclear complex at Natanz, and ultimately affected the software, so that the nuclear centrifuges that produce uranium sped up and slowed down until they spun out of control. That was the essence of the Stuxnet attack, known by the code name Olympic Games.

Olympic Games . . . was the first truly sophisticated state-on-state attack. It opened the floodgates. They probably would have opened anyway to other states conducting fairly sophisticated attacks, whether it was Russia against the United States or the Iranians against Saudi Arabia or North Korea against Sony or China against industrial companies.

BAS: Are a lot of implants sitting in US systems currently?

DS: We’ve seen warnings from the Department of Homeland Security about the electric grid. But we think that there are hundreds of thousands—if not millions—of other implants in other systems. We place implants in systems around the world—“we” being the National Security Agency and US Cyber Command.

Americans get rightly upset when they hear that there are Russian implants in the utility grid, and they wonder what the intent is. Because if you look at an implant, you may know what it can do, but you don’t know what the intent is. Is it being reserved for war time? Is it there to be discovered, and let you know that we’re watching you?

But Americans frequently don’t think very much about the implants that the US puts in foreign systems. Of course, if we were to establish any global norms that said utility systems are off limits or election systems are off limits, we’d have to be prepared to agree to those same norms. It’s not at all clear to me that our intelligence agencies would be willing to give up what they have gained from putting implants in foreign systems.

BAS: You’ve written that the United States has the most powerful offensive cyber force in the world, but is lousy on cyber defense. Why is that?

DS: The reason we’re lousy on cyber defense is we have so much to defend. In cyber conflict, the advantage goes to the least-wired society attacking the most-wired society. This is why it’s the perfect weapon for the North Koreans. You probably have more IP addresses on your block in Chicago than the North Koreans have in the entire country.

And in the United States, the attack surface has expanded dramatically just in the past couple of years. Think about your house. Ten years ago, you probably had one or two internet-connected devices in your house, maybe a laptop or a desktop computer.

Now you’ve got a desktop computer that’s internet-connected. You have a wireless printer that’s internet-connected. You might have an Alexa down in the kitchen or your bedroom that is internet-connected. You have a smart TV. You might have an internet-connected refrigerator. I haven’t yet figured out what I’d do with an internet-connected refrigerator, but I guess if it told me to eat less, that would be useful, right? You’ve got internet connectivity in your car now. Once we have autonomous vehicles, you’ll have wildly more internet connectivity in your car. You’ve got security systems outside your house with wireless video cameras, they’re all internet-connected.

We’re bad on defense because we’ve got so many spread-out elements. If you were going to attack the United States, you would attack that 85 percent of internet usage that is not in the hands of the US government. The financial markets, the utilities, the cell phone networks, they’re all in private hands which means they’re all at different levels of protection. Which makes sense. Some stuff is more vital than other stuff. But it gives the attacker so many opportunities.

Flip it on its head and suppose we say, “we’ll teach those North Koreans a lesson” with a cyberattack. As somebody in the book was quoted as saying, “How do you turn the lights off in a country where they’re never turned on?”

BAS: It seems the US government has made some mistakes on cyber and not necessarily learned from them. Chelsea Manning stole and shared military secrets in 2010, then just a few years later National Security Agency subcontractor Edward Snowden released US government secrets. Is the failure to fix things due to this being a really hard problem, or lack of money, or something else?

DS: I think it’s due to the lack of attention at high levels of the political system, bureaucratic inertia, and failure to understand the threat. When Dan Coats, the director of national intelligence, said “the warning lights are blinking red” the other day, in reference to Russian attacks including on the election system, he was deliberately using language that came out of the post-9/11 world.

But nobody put together all the dots pre-9/11, and I think people have had an even harder time putting together the dots in the cyberworld, because there are so many different attackers. There are so many different targets. Because it’s so easy and cheap to do, and because there’s still a huge absence of understanding about the scale on which cyberattacks happen.

In the book, I try to make people think about four different categories of cyberattack.

There’s espionage. Nothing new there, just using cyber to go do what previously was done by tapping phones or opening letters or putting satellites up in the sky that watched activity.

There’s data manipulation, which is much more subtle than most attacks. That’s how you would throw an election if you could get at the electoral results . . . That’s how you would change the blood types of US military personnel if you got into a medical database. That’s how you could change the recipient of money transfers, as the North Koreans did when they got money out of the Bangladeshi Central Bank and routed it to their own accounts in Southeast Asia.

There are attacks for destructive purposes. That’s Olympic Games. It’s also the North Korean attack on Sony. People remember it for the emails released about Angelina Jolie, but in fact it was notable because 70 percent of Sony’s computer systems were basically crippled. Hard drives melted down. That was a destructive attack. So was the attack on the Sands Casino in Las Vegas.

Then there is information warfare, which is on the verge between cyber and something very old that we’ve seen back to Stalin’s day and far earlier.

In the minds of politicians, some commentators, and the popular press, these frequently get all jumbled up. Yet they’re all different, and you have to defend against them all very differently.

BAS: So election manipulation via Facebook would fall into the information-warfare category.

DS: Absolutely, and the way you would combat that is not necessarily to stop it but to reveal where it’s coming from. If you got this notice on your Facebook account that said, “this may look like it’s coming from your next-door neighbor, but actually it looks to us as if it was initially launched from Moscow,” you’d say, “Hmm, that’s interesting. Unless my neighbors have been in Moscow lately, it seems like a strange place from which to post this.”

BAS: What would US citizens, or citizens of any Western democracy, have to actually change in their lives to be properly defended against the risk of major cyberattack?

DS: Before we get to what they would have to change in their lives, they have to debate intelligently what it is we’re trying to do.

Suppose you and I were to sit down over a beer and put together a list of the kinds of civilian-related systems we think should be off limits to state-run cyberattacks.

We come up with: Election systems, the electrical grid, anything that gets in the way of emergency services. Anything that would affect hospitals and nursing homes, homeless shelters, the most vulnerable.

Then we’d say, “Okay, let’s get the United States to come out and negotiate this internationally.” Not in the belief that it’s going to stop all cyberattacks, but with the idea that once you have norms against it, violating them would be like violating the Geneva Convention. Which is to say, you’d get some world condemnation, just as Assad gets when he gasses his own people.

My guess is that the American intelligence agencies would probably step in and say, “Whoa, before we go ban these, do you really want to stop the president from being able to manipulate an election if he believes it’s the least expensive, least life-costly way to deal with a country?”

After all, the US got involved in influencing elections in Italy in 1948 and Latin America in the fifties and sixties, in Japan and South Korea, South Vietnam, the list goes on. It’s not as if we’ve never done this. We just didn’t do it in a computer age.

Now, the electrical grid. You read in the book about a program called Nitro Zeus, which was designed to take out Iran’s grid if we were going to go to war with them, in the hopes that it would end the war without firing a shot. You could imagine the Pentagon or the intelligence agencies saying, “Do we really want to deprive a future president of that option?”

None of these decisions are going to be easy, but if you leave them solely up to the intelligence agencies and generals, you know how they’re going to turn out. To answer your question, we first have to decide, are we willing to give some things up—to say that some things are off limits—in order to buy some more protection for ourselves? We’ve done that in other areas. We don’t use chemical weapons anymore. We don’t use biological weapons. We never signed the land mine treaty, but we don’t use land mines outside of the Korean Peninsula. We’ve agreed to reductions in our nuclear force that are quite major.

So that’s the first thing we need to do: decide what it is we’re trying to get banned. That’s the political side.

Then you have to decide, what are the technological protections you think you can build up? You can do any number of technological protections, but some of them have some civil rights origin to them. If you want a perfectly protected internet, you would have everybody who goes on the internet go on as themselves. But that would also play to the Chinese and the Russians who want to lock up everybody.

BAS: Is something like the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons—which was passed last year and has 14 ratifiers so far—valuable in changing the norm and making a weapon more taboo?

DS: More valuable in the nuclear arena than it would be in cyber. We only have nine states that have nuclear weapons, 70 years after they were first dropped. Which is astounding, because Kennedy thought we would have many more. As you saw from the book, we probably have somewhere between 30 and 40 sophisticated cyber actor states in the world. Then there’s cyber that’s available to non-state actors so cheaply.

For nuclear weapons, you need uranium and plutonium and millions if not billions of dollars’ worth of equipment and facilities. For non-nuclear, for cyber in particular, you just need some good programmers, maybe a few weapons that got stolen out of the National Security Agency’s arsenal to give you a model, some laptops, a case of Red Bull, and you’re good.

BAS: You and others have observed that it may be possible for a government to achieve its political objectives in a conflict by conducting a cyberattack without actually dropping bombs or killing anyone. Is there a way in which cyberwar is superior to bombs and bullets and missiles, in that it could cause less human death and suffering?

DS: Sure. A great thing about cyber is you can dial it up and dial it down. That’s not true for nuclear weapons, and it’s not true for most munitions. You drop them, and you try to make them as precision as you can, but the fact of the matter is, you can’t target them as well as you can target a cyberweapon.

But we’ve seen cases where cyberweapons have been used somewhat indiscriminately. NotPetya, which was used by Russia against the Ukrainians but ended up infecting other countries including Russia. The WannaCry attack last year by the North Koreans, which ended up hitting the British health care system. In all of these, though, we can’t really find a case where you can say definitively that a human being died because of a cyberattack. Whereas you can find many just in the past 24 hours from more conventional kinds of attacks.

The question is not “can cyber be less destructive.” Of course it can, but it can also be more destructive, more broadly, if you end up tripping out an entire utility system for a long period of time. You don’t know exactly who is going to die as a result. It could be somebody on oxygen, but it could be somebody who just can’t see where they’re driving or walking, because the streetlights went out.

BAS: It’s essentially a mass attack on civilians.

DS: It can be, or it could be a very targeted attack.

BAS: I’m personally a little skeptical that governments on the verge of war would back down without at least the threat of human bloodshed.

DS: You may be right. It hasn’t really been tested. But let me give you a reverse example.

In the book, I describe how the United States attacked North Korea’s missile program, and our doubts about whether or not that attack was successful, and whether it was long-lasting.

Imagine for a minute that the Russians and the Chinese and the Americans all think that the others are inside their nuclear warning systems. They don’t have confidence that when they press the big button, their missiles will actually launch. Then all of a sudden, mutually assured destruction goes out the window, because your confidence that you can retaliate is fairly low, or you think that your adversary may not be able to retaliate. That could be very destabilizing. It could lead people to launch earlier, so that they have more backup time if the launch doesn’t work.

BAS: There’s this extreme level of secrecy surrounding cyber operations, even compared to other forms of warfare. Yet we are sort of in a cyber arms race. How does that work when it seems like everyone wants to keep their capabilities hidden?

DS: That’s a great question. I argue in the book that there’s way too much secrecy surrounding cyber. That you can talk about some capabilities, and you can certainly talk about what should and should not be off limits, without revealing huge amounts about your own specific capabilities. Frankly, since the United States has already lost many of its cyberweapons—first, the programs in the Snowden attack, then, the actual code in the Shadow Brokers attack—who are we kidding [to think] our adversaries don’t have a pretty good understanding of what we can do? But in those cases, we wouldn’t even admit that the WannaCry attack was based in part on a US-designed vulnerability.

If you transfer that to the physical world and imagine that we had lost some of our missile technology, and it got shot back at an ally like Britain, there would probably be court martials over who lost this stuff. But because it’s complicated, it’s a different thing.

BAS: Are there any signs that states are building their cyber arsenals in a deliberately visible way, so that they might act as deterrents?

DS: Not yet, although I think the more that gets published about individual cyberattacks, whether they are foreign or American-led, the more you’re heading in that direction. If that’s one of the utilities of the book, then that’s a small contribution to a little bit of visibility.

BAS: Because deterrence is better than the chaos of not knowing.

DS: Yeah, you’re not going to get a deterrent effect unless there’s a pretty good understanding around the world of what it is you can do.

BAS: How is the US government’s secrecy about cyberweapons making Americans less safe?

DS: It is failing to create that deterrence, and it is getting in the way of us having a much needed, much overdue debate about how we want to use our own weapons, how we want to behave in this realm, so that we begin to set some standards for others.

BAS: You covered the theft of US Office of Personnel Management files, which the public learned about in 2015. As you note, the Chinese weren’t using the stolen information to conduct financial scams, as some at first thought, but rather to make a giant database they could mine and analyze. What are the implications of big data capabilities for espionage?

DS: This goes beyond espionage. When you’ve got the data on 7 percent of the American population, an elite 7 percent that either have or have attempted to get security clearances, then you can begin to put together a pretty good operational sense of who may be working on what and who knows whom. It’s much more than just plain espionage. It can be operationally useful. I think that’s what the Chinese were doing.

The US government never publicly blamed the Chinese for the attack, and OPM’s response was to give everybody whose records were compromised a year of free credit protection. Well, thanks very much. All that seemed to do was cement the thought that OPM had no idea what was going on and what was happening to it.

BAS: This is something that couldn’t be done before. First of all, being able to steal all this data, but then also, having the computer power to crunch it.

DS: Right. Ten years ago, you wouldn’t have known what to do with 22 million records.

BAS: Is the US doing this kind of thing too?

DS: Well, it’s interesting that Jim Clapper, when he was still the Director of National Intelligence, said admiringly of the OPM hack, “If we had the opportunity to do it, I’m sure we would too.” That was interesting, because, first, it left open the question: Are we, can we? But secondly, it left open the question that he thinks that should not be banned. That that’s within the realm of ordinary espionage.

BAS: You wrote in The Perfect Weapon that at the beginning of this decade, the cyber world “was, as Obama put it, the ‘wild, wild West,’ in which countries, terrorists, and tech companies constantly tested the boundaries with few repercussions.” Are we still in Wild West mode?

DS: Yes, we are. I don’t think a whole lot has changed in that regard. In fact, we’ve sort of stepped backwards some, because the activity at the UN over setting standards has kind of frozen. In the United States, the office of the White House cybersecurity coordinator has been eliminated, meaning that even within the US, there isn’t much of the debate there needs to be about the trade-offs between offense and defense.

BAS: Are you seeing anything start to emerge in terms of how laws and treaties might govern cyber?

DS: There are a lot think-tanks discussing norms, and some very good work has been done on that from Stanford to Berkeley to MIT to Harvard to Chicago. There’s been a lot of interesting thinking. But I can’t say that it’s infected the US government terribly deeply at this point.

BAS: I suppose the United States would have to be involved for any kind of restriction to be meaningful?

DS: I think the US, China, and Russia would all have to be involved. That’s true if you were going to set any kind of norm on any big thing. Doing the Paris Agreement without the US is hard. Doing a cyber agreement without the US would be even harder.

BAS: What are your thoughts on the movement among some tech workers to try to stop their companies from being government contractors on AI and cyber?

DS: The biggest case is the effort to make sure that Google stops working on Project Maven, which was an AI project that involved drones. This simply tells you how much the world has changed since the Cold War. The Cold War contractors like Lockheed Martin or Boeing or Raytheon, their main customers in the world were the US government. There was no question they were going to get on board with the US government efforts to go do this kind of thing.

In this world, the modern world of tech companies, their main customers are overseas. They’re companies, they’re consumers. They’re deeply suspicious that the United States government is inside Google’s systems or Microsoft’s or Apple’s. The companies have to go to some length to show their independence.

Then they’re staffed by young, largely libertarian workers, a lot of libertarian workers who don’t believe that this comports with the mission of the firms. That’s a challenge that American companies and the US government never had to face during the Cold War.

That’s got to be one of the first reasons that we have this more public discussion of how we’re using our cyberweapons. Because if you don’t convince those workers that this is ultimately for national and global good, then you’re going to be shut out of some of the biggest innovations that are out there.

BAS: Beyond New York Times reporting, do you think the media’s doing a sufficiently good job covering cyber, and is there anything it could be doing better?

DS: The first thing is, we need more of this. We need a generation of reporters as conversant in cyber as Cold War reporters were conversant in nuclear weapons and nuclear strategy. The good news is that, because so much of this overlaps with coverage of Silicon Valley, there’s a lot of talent out there. We need to get publications to go focus on it, not just at the highly technical level—which is done pretty well—but also at a broader level, so that people begin to understand how this fits into national strategy.

That’s going to take some time. We’re going to need to train a generation of journalists to do this the way journalists had to be trained in strategic studies in the fifties and sixties and seventies. That’s going to take a significant investment at a time that the journalism industry is pretty challenged for investment.

I’m not worried about it that much at the level of the New York Times, the Washington Post, and the Wall Street Journal. I’m not worried about it for specialty publications like the Bulletin where there’s an understanding right away of why this is critical. But getting that to spread more widely, that’s going to be a challenge.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

I’ve read Mr. Sanger’s book and it is fascinating, and definitely frightening. Cyber warfare can do immense damage (long term damage) to infrastructure and we need to come to terms with the reality of this new dimension of conflict.

Just out of curiosity, I wonder if Ms. Eaves could explain the relevance of the black bear she mentions to the subject matter of the interview with Mr. Sanger.