Bomb cyclones and breadbaskets: How climate, food, and political unrest intersect

By David Harary, Sunny Petzinger | October 8, 2019

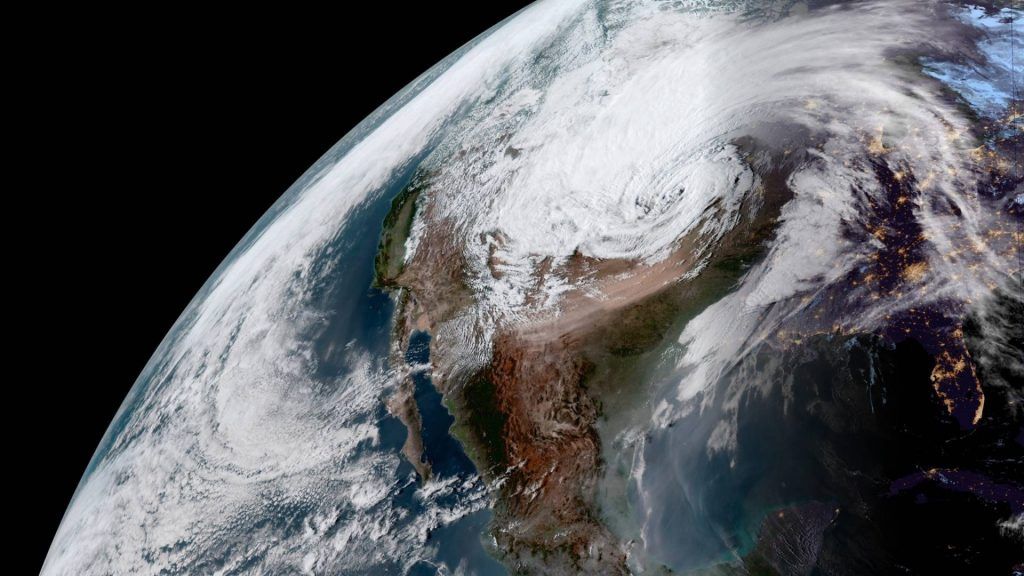

Bomb cyclone storm over the United States in March, 2019. Satellite image courtesy of NOAA/NESDIS/STAR.

Bomb cyclone storm over the United States in March, 2019. Satellite image courtesy of NOAA/NESDIS/STAR.

The torrential downpour, ice, and eventual flooding of the US plains on March 15 and 16 left ranchers stunned. The aptly named “bomb cyclone”—the official term employed by meteorologists—brought increased economic anguish to the Midwest. Vast stretches of productive farmland were flooded and rendered unusable, as cattle corpses rotted. Estimates of the impacts to just Nebraska’s livestock sector topped $400 million. Tack on another estimated $440 million in losses to the Cornhusker state’s row crops, plus $449 million in infrastructure costs, and that makes for more than $1.3 billion in total direct costs from just one extreme weather event in just one state. Total economic losses across the Midwest from the record-breaking flooding this spring are now estimated to be over $12.5 billion.

With damages still being tallied even now, the full impact of lost stored grain, feed, and cattle on the 2019 planting season is still unknown. While grain prices did initially increase substantially, a combination of both strong global supply and shifting international trade policies has since allowed prices to drop. Foreign markets that rely on US corn and beef may be at a particularly vulnerable junction. As the largest producer of these two commodities in the world, any shocks to the US agricultural market can have a significant impact on food security and political stability overseas.

As climate change continues to increase both the frequency and magnitude of extreme weather events, extreme consequences can emerge across and downstream from these supply chains. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s latest report discusses at length the challenges that increasing global population and climatic volatility pose to food and water scarcity—and, consequently, to social and economic systems. As a result, weather and climate forecasting— coupled with the computer-aided modeling of economic and political resilience to such events—could help improve predictions of political flashpoints greatly at a time of unprecedented environmental change.

It’s not all academic. The economic and political implications of food security are very real, as can be seen throughout history: Riots over the lack of bread in St. Petersburg played a key role in the early days of the Russian Revolution of 1917, just like the famine that preceded the French Revolution of 1789—when Marie Antoinette allegedly responded to news of bread shortages by saying “Let them eat cake.” More recently, the Arab Spring provided an important case study in how extreme weather events in agriculturally productive places can affect the global market price of food—thereby catalyzing social unrest, political instability, and conflict elsewhere in the world. Drought, exacerbated by climate change, in modern Russia—still one of the breadbaskets of the world—compelled Russian President Vladimir Putin to withhold agricultural exports from the global marketplace, which in turn led to price shocks to food in the Middle East and North Africa because of their reliance on staple food imports from abroad. (To be sure, Russia’s trade ban was exacerbated by occurring in combination with other shortages.)

To measure the time lag between international food prices and the response in domestic consumer markets, trade analysts often use an indicator called the “pass-through coefficient.” A lower coefficient indicates local food markets are more insulated from international price spikes while a higher coefficient means domestic markets are more susceptible to global price shifts. The pass-through coefficient of many Middle Eastern and North African countries remains high, demonstrating significant vulnerability to international price fluctuations.

Raising the heat. This is not to say that one extreme weather event will definitely cause political instability or uprisings. Instead, a confluence of factors—including environmental degradation—raise concern and risk in countries most vulnerable to further resource shortages, which can in turn serve as catalysts for outbreaks of social and political unrest.

The bottom line is that in the case of the Midwestern bomb cyclone and other extreme weather events in the United States, it is important to look at the impacts on downstream economies as well. For example, Central America’s Northern Triangle region—consisting of the countries of Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador—is a region where climate change and food insecurity is already directly responsible for driving vulnerable populations to emigrate from their homeland. Over the last decade, the Northern Triangle has been plagued by environmental problems: coffee rust disease, (compounded by rising night-time temperatures); droughts brought on by years of El Nino; and an extended dry season have decimated Central American crop production, creating the appropriately nicknamed “Dry Corridor.” Consequently, countries in this region must increasingly rely on imports coming from more stable economies abroad—such as the United States. Since 2006, US farm and food exports to the Northern Triangle have doubled, to compensate for the decrease in crop production in the region. So when a stable agricultural producers like the United States is hit so severely by climate change, that crop shortfall has a ripple effect on the entire global food market—with countries with high pass-through coefficients being especially vulnerable, such as the smaller Latin American countries of the Northern Triangle, and nearby Nicaragua.

As part of the Dry Corridor, Nicaragua relies greatly on imports of US food products such as corn, soy, and dairy. Moreover, the country’s diet consists largely of carbohydrates and processed foods that are made of these products. As one of the poorest countries in the Western Hemisphere, Nicaragua already faces severe chronic malnutrition. According to the World Food Program, an estimated 47 percent of the region’s households are considered to be food insecure—meaning that they are unable to bring sufficient amounts of safe and nutritious food to the table The added stress of fluctuating commodity prices can therefore even further increase the region’s food insecurity.

The nexus between the environment, the economy… and war. When combined with pre-existing resource insecurity, social and political fragility, and long-standing gang violence, increased food scarcity will only magnify the possibility of violent uprisings and armed conflict in the Northern Triangle and possibly Nicaragua. Recent drought has already contributed to significant social and political tension in Central America; over 2.8 million people in the region have gone hungry as a result of this drought. Such increased water and food insecurity has created internal territorial conflicts, which has triggered greater migration toward Mexico and the United States. These challenges are only worsened by weak, corrupt, and ineffective governance in the region. In Nicaragua, President Daniel Ortega’s authoritarian regime spurred deadly political unrest last year. Coupled with severe economic contraction and mediocre agriculture productivity, Nicaragua could be the source of the next major migration crisis in Central America.

While corruption, inadequate law enforcement, and entrenched criminal networks have played a large role in Central America’s disarray in recent years, experts say that local environmental factors have also been a significant factor in the rise of resource competition, migration, and armed conflict. Worse still are the compounded effects of skilled farmers leaving their trade, soil erosion and degradation, and loss of arable land.

One particularly bad drought between 2014 and 2016 damaged over 75 percent of Guatemalan corn. This drought has helped induce further hunger in a country where over 47 percent of children are already chronically malnourished. Such massive insecurity pushed rural Guatemalans into urban areas with few opportunities for employment and subsequently left empty rural areas open to violent gangs and drug cartels. Throughout the Dry Corridor, the drought and its consequent food insecurity was determined to be the single greatest motivating factor for emigres leaving the affected area.

The consequences of extreme weather events, even in well-developed countries, can create cascading price shocks for humanity’s most basic agricultural commodities, such as wheat, corn, rice, and soybeans. The Midwestern bomb cyclone and the growing impact of climate change on US breadbasket states presents yet another risk for instability in alreadyvolatile regions. It serves as an example to why analysts should actively be including severe weather and climate change when examining the complex nexus of national security and state fragility, so that they can better enable policymakers to try to alleviate such risks—rather than scrambling to react to them only once they’ve already occurred.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: climate change, cyclones, food security, hurricanes, migration, resiliency

Topics: Analysis, Climate Change

Food for thought !