In case you missed it: Twitter Chat Q&A transcript on climate change, warmer forests

By Dan Drollette Jr | July 3, 2020

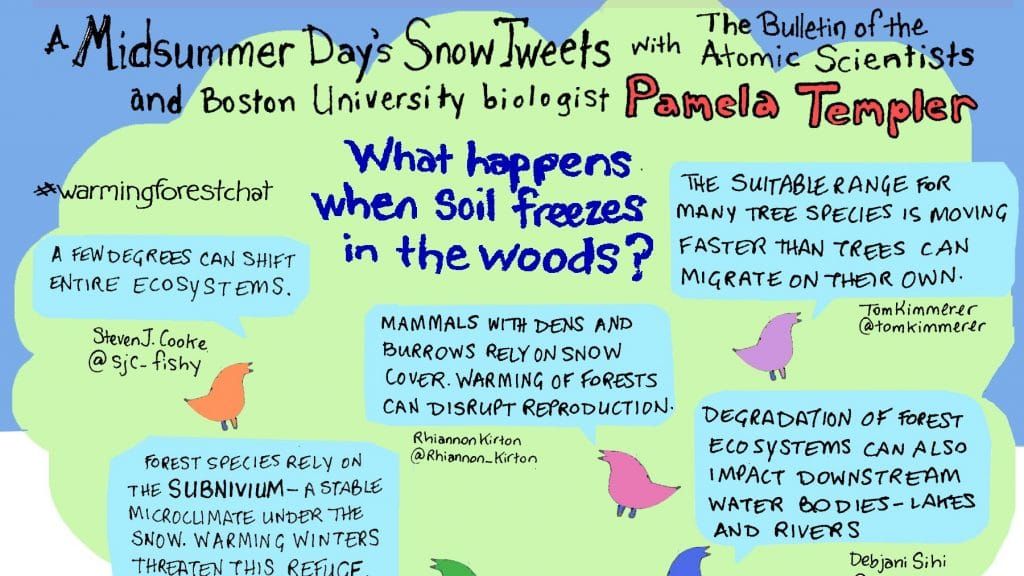

Image courtesy of Karen Romano Young

Image courtesy of Karen Romano Young

Last week, the Bulletin hosted a Twitter Chat, #WarmingForestChat, to allow readers to follow up on an interview with Boston University biologist PamelaTempler about the impact of climate change on the Northern Forest. (See “Shorter, warmer winters, less snow. What next?”) In this question-and-answer session on Twitter, members of the public could ask questions about the impact of warmer winters on cold-adapted forests—not only of Templer, but about a dozen other scientists as well, including ecologists, fish biologists, botanists, mammalogists, and entomologists, among others.

It turns out that despite being labeled the so-called “dormant” season, a lot is going on during winter in the north country—assuming a good blanket of snow is there to act as an insulator. But with climate change, winters are getting shorter and warmer, so there will be less snow to protect the roots, microfauna, and microflora below. Which will cause a cascade of huge, differing effects down the line.

You can read some of the highlights of the Twitter Chat in the transcript below.

The full, premium article/interview with Templer is available here, and is free-access until July 31, 2020.

(Editor’s note: This Twitter Chat has been condensed and edited for length and clarity.)

Question 1: Temperatures at higher latitudes, and in winter, are warming faster than at lower latitudes or in other seasons. How much so, and why?

Answer 1: Winters at Hubbard Brook, rest of northeastern US, and parts of Canada now 5 degrees F hotter than 100 years ago. Everything cold is warming fastest: winter more than summer, high more than low latitudes, night more than day.

— Pamela Templer – @phtempler

A1: Since the 1980s, surface air temperatures overland have increased at about twice the rate of temperatures over oceans. Northern Hemisphere has more land masses, and thus, faster rates of warming.

Benjamin Zuckerberg — @ZuckerbergLab

A1: The estimates are that high latitudes are warming about twice as fast as lower latitudes. It’s in big part due to the large-scale atmospheric patterns that are carrying energy towards the Poles, making them warm faster.

Cynthia Gerlein-Safdi — @CGerleinSafdi

A1: To chime in, temperature increases have been recorded across all seasons at Hubbard Brook, but winter temperatures have risen the most, with avg winter temps 3.5ºF warmer since 1956. Summer & fall temperatures have warmed by 2.3 F and spring temperatures are up by 2.2 F.

Lindsey Rustad — @LindseyRustad

A1: Tree ranges are constantly changing. Trees are still migrating (yes, trees migrate) following the last glaciation. Suitable range for many tree species is moving faster than trees can migrate on their own as forests warm rapidly.

Tom Kimmerer, PhD — @tomkimmerer

A1: I’ll start with intro… I am fish biologist… So why wud I be involved in a chat re winter forest warming? Well – everything that happens in upland (forest) areas influences downstream waters… Our lakes & rivers are surrounded by forest (or used to be). North temperate areas are transitional… so a few degrees C increase has potential to shift entire ecosystems.

Steven J. Cooke — @SJC_fishy

A1: I work with mammals…but warming winters, especially in Canada have wide ranging impacts for many species. Huckleberries, a key food for grizzlies in the Rocky Mountains, require deep snow and can be damaged by early melt/exposure to frost.

Rhiannon Kirton — @Rhiannon_Kirton

Q2: Less snow on the ground means what for forests and forest inhabitants?

A2: Loss of snow can lead to a phenotypic mismatch for species that change their coat to match snow. Snowshoe hare is a classic example. Mismatches have important survival consequences. Check out @scottmillslab, @marketazimova, and @evancwilson. #WarmingForestChat

— Benjamin Zuckerberg (@ZuckerbergLab) June 25, 2020

A2: Frozen soils can damage roots, microbes, insects, and reduce forest carbon sequestration up to 40%. Snow acts as blanket. Less snow means less soil insulation of all that lives in the soil below. Even in mild winter, if temperatures are below freezing and soils not covered with snow, soil more likely to freeze.

Pamela Templer — @phtempler

A2: There will be winners and losers. Boreal species such as spruce, paper birch, fir, are already in trouble. Fast-moving opportunists like red maple are expanding. We will need to engage in assisted migration: planting trees outside of their geographical range to keep them from becoming extinct. We don’t know how to do this without disrupting forest ecology.

Tom Kimmerer, PhD — @tomkimmerer

A2: Many forest species (herps, small mammals, birds) depend on the subnivium – a stable microclimate under the snow – for overwintering, refuge, and escape from harsh winter weather. Warming winters and the loss of snow threatens this refuge.

Benjamin Zuckerberg — @ZuckerbergLab

A2: Less snow is going to change both the amount of water available to plants, as well as the timing of when this water is available. Snowpack used to melt at the beginning of the growing season, when plants needed it the most.

Cynthia Gerlein-Safdi — @CGerleinSafdi

A2: Less snow cover is impacting many species but for mammals with dens or burrows that rely on snow cover, warming of forests has the potential to disrupt the reproductive cycles of mammal species such as the wolverine.

Rhiannon Kirton — @Rhiannon_Kirton

A2: Same thing in fish – how they store energy, reproductive cues, etc – may all be messed up. In other words, the effects of altered winters may cascade across seasons.

Steven J. Cooke — @SJC_fishy

A2: Even forest birds, like ruffed grouse, burrow under the snow to escape predation and roost in warmer conditions. Using these “snow roosts” grouse even lower their stress levels during winter. Loss of snow will lead to the loss of these important refugia.

Benjamin Zuckerberg — @ZuckerbergLab

A2: For organisms that live IN lakes (under ice), less snow pack in winter MAY reduce winter kill. Snow blocks light that can normally shine through ice. BUT less snow pack means less water to melt in spring which will change character of streams, rivers and wetlands.

Steven J. Cooke — @SJC_fishy

Q3: What are the implications for humans? How will warming forests affect local populations and beyond?

Climate change is expected to alter tree species distributions by changing air T, soil T, and precipitation. This is already happening: trees in eastern North America are shifting West and North. #WarmingForestChat

— Tom Kimmerer, PhD (@tomkimmerer) June 25, 2020

A3: In short-term:warmer temperatures can have some benefit with longer growing seasons for farmers and foresters and lower heating bills in winter. But, warmer temperatures harm people through heat waves, drought, storm surges, and other extreme weather events.

Pamela Templer — @phtempler

A3: declining snowpack and damage to trees will lead reduced ability for forests to improve water and air quality.

Jenna — @msjerindy

A3: And then one wonders how (legitimate) fear of ticks/Lyme will change our relationship with nature. Daily tick checks r part of life for our family but others may simply stop going into nature and pave their backyards.

Steven J. Cooke — @SJC_fishy

A3: It’s not just moose that are going to suffer from warming forests and ticks…Lyme disease, which affects people, is becoming far more widespread in Canada and the US as tick season is extended by warmer springs.

Rhiannon Kirton — @Rhiannon_Kirton

Q4: Pam Templer found a 40 percent decline in the amount of carbon dioxide absorbed by sugar maples. We recently published an article showing that part of the Amazon rainforest had switched from absorbing CO2 to releasing it. Is that a coming trend for forests?

A4: The boreal forest is of global importance for many reasons! It is expected that with warming, decreases in permafrost will disturb the root systems of trees in the boreal forest and changes in tree stability may lead to release of methane

Rhiannon Kirton — @Rhiannon_Kirton

A4: Anything that causes plants to reduce carbon uptake during photosynthesis or for plants and soils to release more carbon during respiration means forests store less carbon.

Pam Templer — @phtempler

A4: Climate change has been making droughts more frequent and more intense. Plants close off their stomata and stop uptaking CO2 to preserve water during a drought, but soil decomposition that releases CO2 does not stop, turning forests into net carbon emitters.

Cynthia Gerlein-Safdi — @CGerleinSafdi

Q5: In her interview with the Bulletin, Templer talks about the phrase “weather whiplash.” What does that mean? Is it a new phenomenon, and what is its effect on ecosystems?

A5: More frequent and severe weather events will occur as we warm. This includes flooding and wildfires. We are already seeing this in Canada in places like Fort McMurray #warmingforestchat https://t.co/naINQafgTV

— Rhi | keep your ass at home | Kirton (@Rhiannon_Kirton) June 25, 2020

This has impacts for mammal communities and, to my surprise, mushrooms!! Find this interesting article I came across, below. https://t.co/VzQVzFXvih

— Rhi | keep your ass at home | Kirton (@Rhiannon_Kirton) June 25, 2020

A5: Winter whiplash is huge swings in weather not seen in past. Examples include 70-degree days followed by snowy blizzards, then hot days with flooding caused by rapidly melting snow.

Pam Templer — @phtempler

A5: We are studying possible increases in the frequency or severity of extreme winter weather events, like ice storms. These extremes can have big impacts on our forests and communities. Lindsey Rustad — @LindseyRustad

A5: Winter weather whiplash happens when conditions produce a back‐and‐forth change in winter weather. Winter birds may be impacted by winter extreme events, such as polar vortexes, that may cause mass mortality (especially for warm-adapted resident birds).

Benjamin Zuckerberg — @ZuckerbergLab

A5: It means that there are more and more frequent swings in weather: torrential rains to drought, hot to cold. Plants have adapted to the climate they live in and many might not survive the new extreme weather events we are seeing in many parts of the world.

Cynthia Gerlein-Safdi — @CGerleinSafdi

Q6: Are the consequences of warming forests already happening or are they in the future? What are the experiments elsewhere showing?

A6: It is happening and may likely increase in the future. A few examples are invasion by nonnative plant species, species shift. These have consequences on insect-pollinators too. #WarmingForestChat https://t.co/GE0ccSiJKb

— debjani sihi (@darisihi) June 25, 2020

Thanks to long-term data collected by the USFS Forest Inventory & Analysis Program, we can already detect eastern forest tree migration north and west.

Tom Kimmerer, PhD — @tomkimmerer

A6: I think that pretty much everybody agrees that we are already seeing the effects of warming forests all over the world: pest invasions facilitated by drought-fragilized trees, large diebacks, new invasive species are being seen everywhere.

Cynthia Gerlein-Safdi — @CGerleinSafdi

A6: In rivers/streams already seeing mid winter runoff events – what used to be snow is now rain or mid-winter melts and it is changing stream function in winter and in summer.

Steven J. Cooke — @SJC_fishy

A6: They are already happening. Ecological responses to climate change (range shifts, earlier phenology, community changes) are being studied and documented across the world’s forests. Future warming will only worsen other stressors (fragmentation, pollution).

Benjamin Zuckerberg — @ZuckerbergLab

A6: Currently, pests increasing in numbers and range, so more diseases are hitting trees and people. Examples include HemlockWoolyAdelgid, barkbeetles, WestNileVirus, LymeDisease.

Pam Templer — @phtempler

Q7: What are one or two key things you would tell people about how warming forests will affect their lives?

A7: Trees provide many functions that benefit humans, including regulating our climate in general, keeping us cool in winter, filtering our air and water. We need to protect them. We need to conserve and protect our forests and urban trees to ensure their health and functioning, and human well-being.

Pam Templer — @phtempler

A7: Forests are keys to the biodiversity of our planet, the cleanliness of our water, and large forests even affect weather patterns! Warming forests will look different and we might lose some of those key ecosystems! But it’s not too late for climate action.

Cynthia Gerlein-Safdi — @CGerleinSafdi

A7: Warming temperatures affect virtually all physical, chemical & biological reactions, & will have a myriad of effects big and small. Right now in the Northeast, anglers are bemoaning the warm stream temperatures which affect cold water fish like trout & salmon; Lindsey Rustad — @LindseyRustad

A7: So much of what will happen will be unexpected… We can model but the interactions will be complex and difficult to predict feedbacks, synergies, etc. What happens in forests influences function of wetlands, lakes and rivers. Can’t think of forests as isolated from the rest of the landscape.

Steven J. Cooke — @SJC_fishy

A7: Forests are important for the health of humans, wildlife and the whole biosphere. We need to take a holistic approach and make sure we conserve the forests we have left because they are so so important and the consequences are far-reaching.

Rhiannon Kirton — @Rhiannon_Kirton

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Northern Forest, climate change, climate crisis, global warming, warming forest

Topics: Climate Change