Infodemic Monitor

Coronavirus disinformation adds conspiratorial fuel to a volatile Middle East

By Samikshya Siwakoti, Jacob N. Shapiro, Isra Thange, Alaa Ghoneim, September 7, 2020

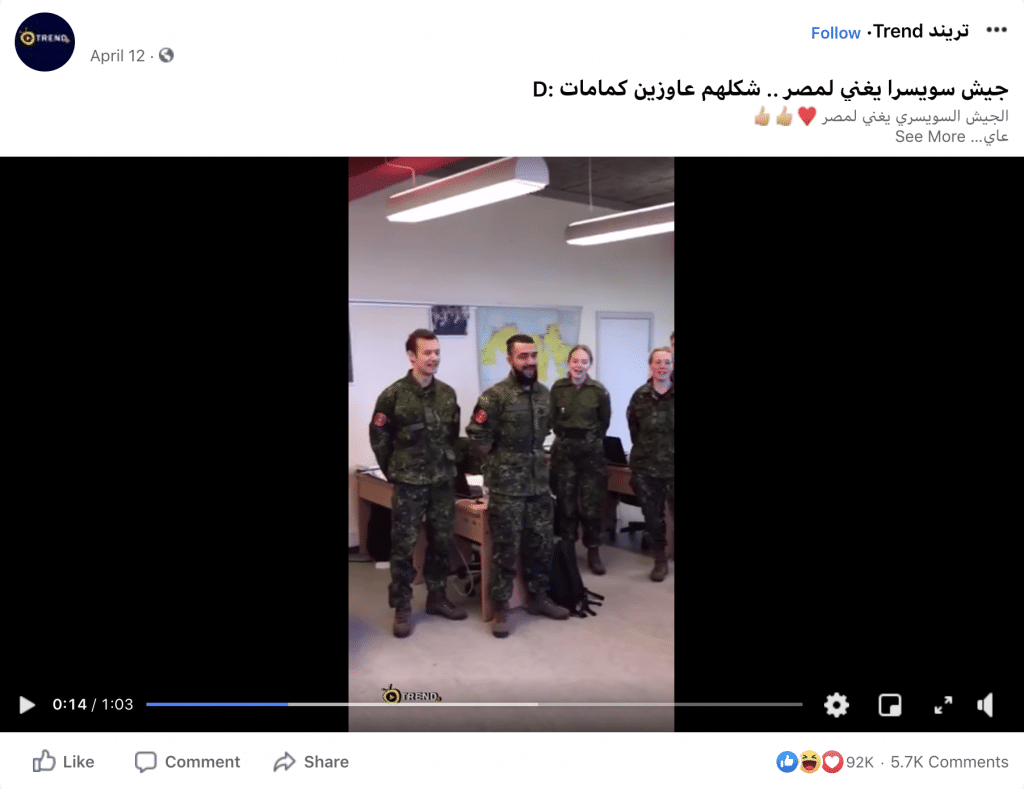

A Facebook post falsely claims that Swiss troops sang to Egyptians in a plea for masks. MISBAR, an independent Arabic fact-checking platform, reported the video was actually of Danish soldiers singing and was shot before the pandemic. Screenshot: Facebook.

A Facebook post falsely claims that Swiss troops sang to Egyptians in a plea for masks. MISBAR, an independent Arabic fact-checking platform, reported the video was actually of Danish soldiers singing and was shot before the pandemic. Screenshot: Facebook.

If some sources in the Middle East and North Africa are to be believed, China has declared nuclear war on the United States as retaliation for the latter creating the coronavirus to destroy the Chinese economy. Other equally dubious sources could lead a person to believe that 5G technology is responsible for the virus, or that COVID-19 spreads the most in countries located on the 40th parallel north.

When the first cases of COVID-19 were recorded in the region in late January, many Middle Eastern and North African governments responded quickly and decisively to the pandemic by instituting lockdowns and other measures to prevent the spread of the virus. Yet, as part of a Princeton University project to track COVID-19 disinformation narratives, we can say these physical containment measures have done little to contain the spread of misinformation.

Misinformation has been a part of political life in the Middle East and North Africa for years; the coronavirus era has proved no exception. In the past eight months, we recorded 403 independent COVID-19 misinformation narratives in the region. These narratives, which represent general storylines which then get repeated in tweets, posts, or online articles, make up a little over 16 percent of the 2,471 storylines our project has collected from countries around the world so far.

The sources of misinformation—ranging from social media users to heads of state—painted either a bleaker picture than is actually warranted by the facts or gave false hope that the containment and eradication of the virus was at hand.

On the bleak side of the spectrum: In Algeria and the Palestinian territories, fake news on social media suggested that some cities or jurisdictions had extended a lockdown. In Egypt, false rumors claimed that newspaper presses were stopped and schools were turned into field hospitals. Again in Algeria, social media users falsely claimed that the state had instituted a moratorium on marriages. In the UAE, social media users falsely claimed that malls and dressing rooms were shuttered due to the spread of the coronavirus.

Over the summer, celebrities in the region were allegedly testing positive for or dying from the coronavirus with alarming frequency. But Egyptian singers Hany Shaker and Tamer Hosny, Iraqi actress Inaam Al-Rubaii, and Algerian singer Cheb Khaled have all denied rumors about their health, countering misinformation about them.

Regular people weren’t spared, either. In Bahrain, one false story alleged that more than 70 delivery drivers had tested positive for the virus. In Egypt rumors spread on social media that students were getting infected during school exams. Some stories even falsely claimed that students sitting for thanawaya a’mma exams, or the national college entrance exams, were passing out or dying in testing rooms.

On the false hope side of the ledger, other narratives downplayed the severity of the virus and declared that life was finally returning to normal. In the early months of the pandemic, some people falsely claimed that certain drugs, such as Viagra, were effective against the virus or spread false news about the imminent discovery of a vaccine. One false story spread on Facebook claimed that a treatment for the virus was already available in all Iraqi pharmacies. Another rumor in Egypt claimed that the virus had already mutated into a weaker form. Common too, were false claims that emergency response measures were being relaxed. In Egypt and Algeria, wedding venues would allegedly open. In Saudi Arabia, international flights were set to resume. Tunisia would soon lift its quarantine.

While certainly optimistic, none of these rumors were true.

Another trend we’ve seen in the region is the widespread portrayal of countries as being exceptionally successful in combating COVID-19.

Peddlers of false information often proclaimed their country had a superior national response. In Syria, for example, a Facebook post claimed that a child prodigy discovered a cure for COVID-19. Posts in Egypt commended the generosity of Egyptians through untrue claims that many recovered citizens had donated their plasma to treat others. One story placed the number of alleged donors at 200,000, and another placed the number even higher at 600,000—with both figures being far higher than the roughly 100,000 COVID-19 cases that Egypt has recorded.

A second form of exceptionalism narratives celebrates the superiority of the state, its response to COVID-19, and its domestic health care workers, heaping more praise than is justified by the facts. In Iran, President Hassan Rouhani delivered a speech claiming that his country was responding better to the pandemic than Europe was, despite dealing with international sanctions. In fact, Iran has logged over 378,000 infections, a worse figure than in many European countries.

While false claims often circulate on social media, in Palestinian territories several local and regional news sites falsely reported that an Israeli TV channel admitted that health officials in Gaza were managing the outbreak better than the Israeli government. In Tunisia, a video circulating on social media eventually made it to the news outlet Anahwa.com. It was accompanied by the false claim that Tunisia had defeated the virus. According to the Jordanian fact-checking site Fatabyyano, however, the video showed Italian doctors and nurses celebrating the closure of a COVID-19 hospital wing.

A common trope in COVID-19 misinformation narratives appears to be that other countries are praising a given country's response. Facebook users in Tunisia falsely claimed that the World Health Organization had declared their country to have the best COVID-19 response in Africa, while Twitter users in Saudi Arabia falsely claimed that the organization had praised their country’s digital architecture to be the most successful in fighting the virus.

The trend of fabricated external praise is most common in Egypt, where we recorded stories ranging from the claim that a French magazine had praised President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi for his virus response to tales that the Swiss army was singing praises of Egypt out of desire for medical supplies as well as claims that Italians were thanking Egypt for sending them medical help. In effect, citing an external source allows individuals and states to make false, self-congratulatory claims while lending credibility to the misinformation being circulated.

State officials, political actors, or official media sources accounted for approximately 14 percent of the narratives we’ve found in the region.

Narratives centered around national governments were particularly prominent among the member states of the Gulf Cooperation Council, countries where the state is heavily involved in citizens’ political and economic lives. Much of the misinformation revolving around the state appears to have partisan motives. Pro-regime activists in Syria circulated the false claim that President Bashar al-Assad is personally in a lab searching for a cure to COVID-19, an attempt to increase his popularity. Meanwhile, in Oman, a false rumor spread by several partisan news sites claimed that the state would levy a fine on anyone who discovered a cure to the virus. In Egypt, false claims spread on social media that the government would reduce the time allotted for Friday sermons, an attempt to undermine the government for a perceived infringement on religion.

Government officials themselves were the source of misinformation in several narratives we found. In Israel, the deputy health minister falsely claimed that Israel has the highest rate of coronavirus testing in the world. In early April in Iran, Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei delivered a speech holding the West liable for the pandemic, in addition to sharing the hashtag #COVID1948 on social media, a reference to the 1948 establishment of Israel. Khamenei’s actions are just one example of the several state narratives in Iran that blame other countries for the creation and spread of the pandemic, while continuing to maintain that domestically, the country is returning to normal.

Although there is a lot of misinformation coursing through the media and on social networks in the Middle East and North Africa, there are at least 10 fact-checking platforms in the region, publishing information in both Arabic and English.

In the Middle East and North Africa, false stories perpetuated by a mix of social media users, official media, and political leaders make it difficult for regular people to differentiate what’s true from misinformation. A volatile region where three wars are being fought can ill afford coronavirus-related lies and nationalistic pandemic one-upmanship.

Editor’s note: This is the fourth installment in a series by researchers working with Princeton University’s Empirical Studies of Conflict’s COVID-19 disinformation project. Led by professor Jacob Shapiro and Samikshya Siwakoti—a research specialist for the conflict studies project—students at Princeton and other universities are cataloguing the various false narratives cropping up online about the COVID-19 pandemic. Readers can see the team’s disinformation spreadsheet here.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Coronavirus, Disinformation, Infodemic Monitor, Middle East, North Africa

Topics: Analysis, Disruptive Technologies

Share: [addthis tool="addthis_inline_share_toolbox"]