Making sense of your climate-denying cranky uncle

By John Cook | November 25, 2020

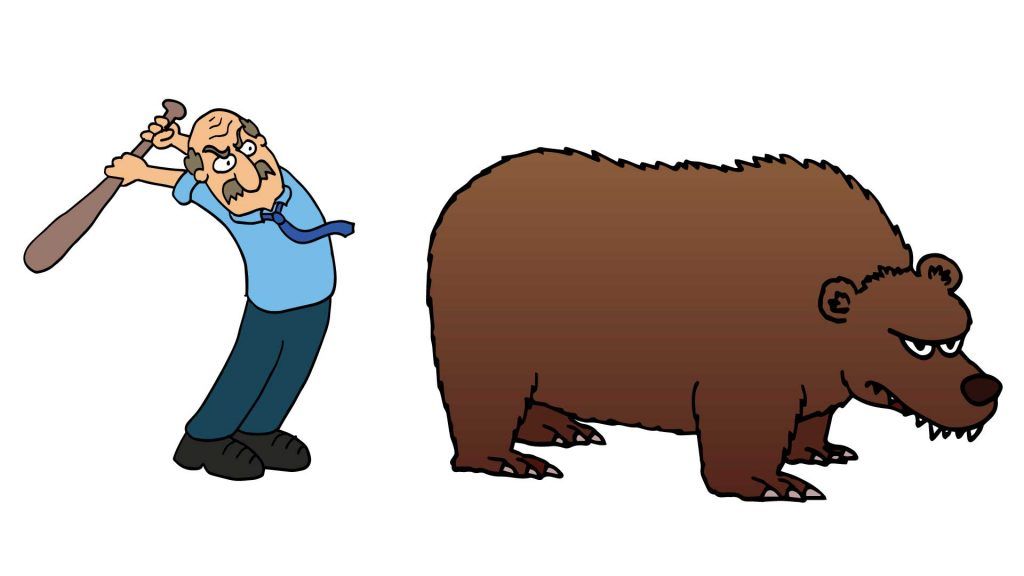

Our climate system is like a cranky beast, that over-reacts to even small prods. Right now, we’re hitting it with a big stick in the form of excessively high carbon emissions from human activity—which our cranky uncle refuses to accept is happening (and ulimately causes the bear to be poked even more). Image courtesy of John Cook, from his Bulletin article “Making sense of your climate-denier”

Our climate system is like a cranky beast, that over-reacts to even small prods. Right now, we’re hitting it with a big stick in the form of excessively high carbon emissions from human activity—which our cranky uncle refuses to accept is happening (and ulimately causes the bear to be poked even more). Image courtesy of John Cook, from his Bulletin article “Making sense of your climate-denier”

One challenge at Thanksgiving dinner is your climate-denying cranky uncle. You’re likely to hear a string of arguments from how cold it was last Tuesday to the whole field of climate science being a hoax.

How do you make sense of your cranky uncle’s arguments? Is there any rationality in irrational science denial? There are two main ways to respond to climate misinformation. Both are effective and ideally, a combination of the two is recommended. But one approach is particularly powerful, equipping you to make sense of misinformation across many topics, not just climate change.

The first approach is what researchers call fact-based correction. You can see through misinformation if you have sufficient understanding of the science. In other words, debunk your cranky uncle’s arguments by explaining the facts.

For example, when you encounter the argument that the weather is cold therefore global warming isn’t real, explain how global warming spans the whole planet (the clue is in the word global). Individual locations may experience bursts of cold weather but overall, the planet is warming due to more heat-trapping greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. This means hot days are becoming more frequent and cold days are happening less often.

A limitation of the fact-based approach is each response only applies to a specific myth. Explaining the concept of global average temperature helps understand the “cold weather disproves global warming” myth. But it doesn’t necessarily help you make sense of other climate myths.

That brings us to the other way of making sense of cranky uncles’ arguments – using logic. Most misinforming arguments employ reasoning fallacies to get to a false conclusion. Identifying fallacies is an elegant and user-friendly way to show that misinformation is misleading. There’s an additional benefit to the logical approach. Learning the techniques of science denial extends beyond a single topic. Understanding a misleading technique in climate change helps you spot the same technique in misinformation in other topics such as COVID-19 or vaccination. I’ll come back to this later.

But first, let’s look at some concrete examples.

There are five overarching categories of misleading techniques in misinformation, summarized with the acronym FLICC: fake experts, logical fallacies, impossible expectations, cherry picking, and conspiracy theories.

Fake experts are people who convey the impression of expertise but don’t have the actual relevant expertise. The clearest example of this strategy is the Global Warming Petition Project, an online petition claiming humans aren’t disrupting climate, signed by 31,000 science graduates. The petition is open to anyone with a science degree so it’s populated by graduates in computer science, medical science, engineering, and a variety of other fields. But over 99 percent of the signatories have no expertise in climate science. The petition is fake experts in bulk.

Logical fallacies are found in arguments where the conclusion doesn’t logically follow from the premises. The most common example in climate misinformation is single cause fallacy – assuming only one factor is causing something when there can be multiple causes. The argument “climate is changing because climate has always changed” assumes that because climate has changed naturally in the past, it must be natural now. That’s like finding a murder victim and arguing “people have died of natural causes in the past so this person must have died of natural causes.”

Impossible expectations involve demanding unrealistic levels of proof from science. For example, the argument “scientists can’t predict the weather next week so how can we expect them to predict climate a century from now?” commits false equivalence—another logical fallacy—as weather is chaotic and hard to predict while climate is weather averaged over time and hence predictable. I can’t predict a coin toss but I can predict a million coin tosses will result in roughly half heads and half tails. Demanding you can predict a single coin toss before predicting a million coin tosses is an impossible expectation.

Cherry picking involves narrowly focusing on evidence that seems to confirm your beliefs while ignoring the bigger picture. Anecdotal thinking is a common form of cherry picking, such as the cold weather argument examined earlier. Who among us hasn’t heard a curmudgeon mutter on a cold day “What happened to global warming?” This is like arguing after Thanksgiving dinner “I feel full. Whatever happened to global hunger?!”

Conspiracy theories and science denial are bosom buddies. How else would a cranky uncle explain why the global scientific community disagrees with him? There are telltale red flags of conspiratorial thinking. Watch out for overriding suspicion: “all the data has been faked.” Conspiracy theorists see nefarious intent everywhere: “scientists are in it for the money!” And they are immune to evidence: “Of course there’s no proof of my conspiracy theory, the conspirators did such a good job covering it up!”

Should we respond to our cranky uncle with facts or logic? I recently published research testing both approaches. We found if people read a fact, then afterwards read a myth countering the fact, the myth cancelled out the fact. But an explanation of the myth’s logical fallacy was effective in neutralizing the myth whether it came before or after the myth. In other words, facts are vulnerable when we send them out into a hostile world but logical explanations are more robust, equipping us with the critical thinking to make sense of misleading arguments.

Other research finds both approaches work. A German study found both the logic and fact-based approaches (which they called technique and topic rebuttals) were effective in neutralizing misinformation. But the researchers also pointed out a key advantage of the logical approach – it could work across domains. Understanding the misleading techniques in one topic helps identify the same techniques in another area.

I found in a 2017 study that explaining the fake expert strategy used by the tobacco industry effectively inoculated participants against climate misinformation in the form of the Global Warming Petition Project. Critical thinking is like a universal vaccine against misinformation, conveying immunity across topics.

But how can this help you at the dinner table during Thanksgiving? Analogies are an elegant technique that help you turn abstract logic explanations into concrete examples. Critical thinking philosophers call this parallel argumentation, an approach used often by late night comedians. “Cold weather disproves global warming? That’s like saying nighttime disproves the sun.” “Climate change is natural because climate has always changed? That’s like arguing smoking doesn’t kill because people have always died of cancer.”

Cranky uncles can be challenging. But responding to their climate denial arguments can also be an opportunity to explain the reasoning fallacies in climate misinformation, potentially increasing people’s critical thinking skills.

So, critical thinking can help get you through Thanksgiving. And help you deal with your own climate-denying, cranky uncle.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: climate change, climate communication, climate crisis, climate denial, climate science, global warming

Topics: Climate Change

There is the belief that if people only knew the facts, they would demand an end to fossil fuels. However, fossil fuels are cheap. For the urban professional class (the people who read these articles), an increase in the cost of energy is not a big deal. Not true for those who are not well to do–including much of the developing world. There is a reality that no major society has made the transition out of poverty without fossil fuels. This is a case of the rich preaching to the poor: Do as we say, not as we did to… Read more »

Like the article suggested, let’s practice our critical thinking skills here. Fossil fuels are cheap? You’re talking about the most heavily subsidized industry in human history. Are you accounting for these costs to taxpayers? Are you accounting for lost productivity in the workforce due to pollution-induced illness. Or the costs to healthcare systems? Let’s try some facts. Fossil fuels are cheap? According to actual statistics, wind and solar are by far the cheapest sources of electricity. I’m not sure how consumers would come out further behind by having vastly cheaper, vastly safer sources of energy made available to them. “There… Read more »