An existential discussion: What is the probability of nuclear war?

By Martin E. Hellman, Vinton G. Cerf | March 18, 2021

Long before Vinton Cerf and Martin Hellman changed the world with their inventions, they were young assistant professors at Stanford University who became fast friends. Chances are that you relied on their innovations today. Cerf is considered one of the “fathers of the internet” for having invented, along with Robert Kahn, the internet’s protocols and architecture, known as Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (TCP/IP). Hellman is seen as a “father of public key cryptography” for having invented, along with Whitfield Diffie and Ralph Merkle, the technology that protects monetary transactions on the internet every day. More than 50 years and two technological revolutions later, the friendship between Vint and Marty—as they know each other—endures. This is despite, or perhaps because of, their sometimes different views. You see, while they do not always agree, they both enjoy a good intellectual debate, especially when the humans they sought to bring together with their inventions face existential threats.

Not long after giving the world public key cryptography, Hellman switched his focus from encryption to efforts that might avoid nuclear war. “What’s the point of developing new algorithms if there’s not likely to be anybody around in 50-100 years?” Hellman recalls thinking at the time. He did not then envision that cybersecurity would also become an existential threat or what it is today—an escalatory step toward nuclear threats that could lead to nuclear use.

Sometime after TCP/IP provided the foundation for the internet, Cerf joined Google as its Chief Internet Evangelist and vice president, where he leads efforts to spread the internet, via global policy development, to billions of people around the world without access. Among other projects, he has also had a hand in supporting NASA’s effort to build an interplanetary internet that operates today.

The world has changed in dramatic ways since Cerf and Hellman met 50 years ago. Yet the foundation of their friendship—good intellectual debates—has not. On a recent private phone call with each other, the two friends discussed the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s project seeking to answer the question, “Should the US use quantitative methods to assess the risks of nuclear war and nuclear terrorism?” While both agree that the US needs to understand the risk of nuclear war, they disagree about whether a quantitative analysis is necessary. What follows are their thoughts, presented here for Bulletin readers.

Quantitative

Martin Hellman

Professor Emeritus, Stanford University

When the risk is highly uncertain, how do you determine who’s right?

.

Is the risk of nuclear deterrence failing acceptable? Former Secretary of Defense James Schlesinger thought so. In a 2009 interview, he stated that the US would need a strong nuclear deterrent “more or less in perpetuity.” In contrast, former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara stated in the 2003 documentary, Fog of War, that “the indefinite combination of human fallibility and nuclear weapons will destroy nations.” So, is the risk of failure acceptable or unacceptable? When nuclear risk is stated in generalities, it is difficult to determine who is right.

In the 1970s, such questions were, at best, of passing interest to me. My research in cryptography consumed me. That wasn’t all bad since it led to the invention of public key cryptography and the foundation of much of modern cybersecurity. But, slowly and painfully, I came to see that my over-focus on career and logic was killing my marriage. Then, in 1981, Ronald Reagan’s assumption of the presidency brought the nuclear threat into sharp focus.

As explained in a book that my wife, Dorothie, and I wrote, I realized that it wasn’t smart to neglect risks either to my marriage or to the planet (and there was a surprising connection between the two). I shifted my research from information security to international security, with a focus on the risk of nuclear deterrence failing. Almost as soon as I looked at that question with new eyes, I saw that the risk of nuclear devastation was unacceptably high. I have continued to develop that line of thinking and here I summarize my current perspective.

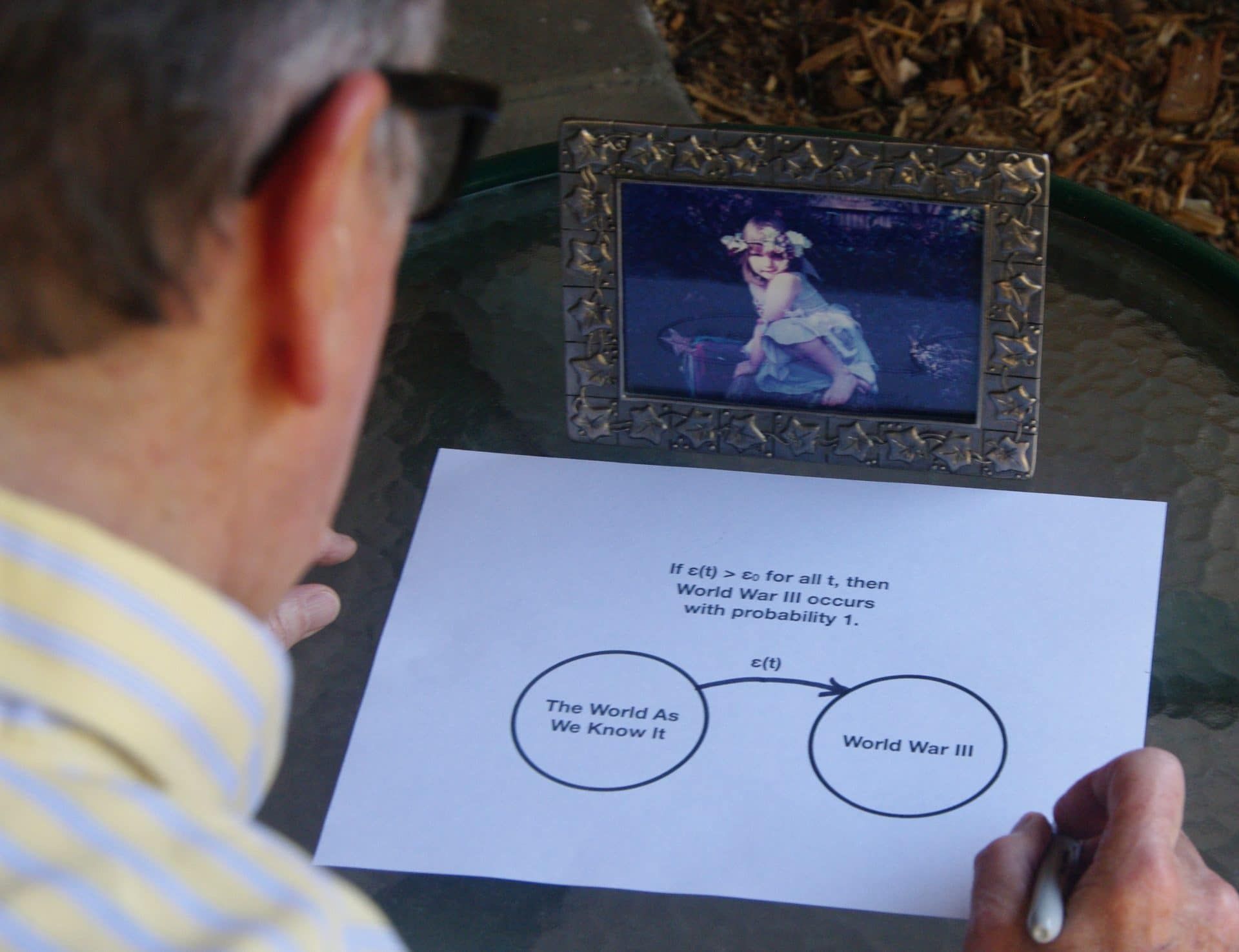

This article uses a simple, quantitative estimate to show that the risk of a full-scale nuclear war is highly unacceptable, and that a child born today may well have less-than-even odds of living out his or her natural life without experiencing the destruction of civilization in a nuclear war.

Some, including my friend and colleague, Vinton Cerf, prefer a qualitative analysis for reasons he explains in his companion article. Others argue that a quantitative estimate of the risk of a full-scale nuclear war is not possible because such an event has never occurred. They are right in the limited sense that it is not possible to determine if the risk of a nuclear war is one percent per year versus two percent per year. But it is possible to upper and lower bound it.

If someone were to propose that the risk were one percent per day, I’d rule that out as far too high because then nuclear war would be almost certain within the next year. Similarly, if someone were to suggest that the probability were one in a million per year, I’d consider that too low because it would imply that nuclear deterrence as currently practiced could work for approximately a million years. Considering the historical record of nuclear near misses, some of which are detailed in Vint’s article, a million years is far too optimistic. (Of course, if humanity survives for another million years, major events will change the risk appreciably. Here, I seek only to estimate the risk over the next year, during which time such changes will be minimal. Extrapolating that annualized estimate to the next several decades also is reasonable, especially given the estimate’s large uncertainty bounds.) These two extreme cases—nuclear catastrophe either in the next year or in a million years—establish initial upper and lower bounds on the risk.

Next, I sought to narrow the range. In my estimation, and based on my extensive study of nuclear risks, ten percent per year is also an upper bound since we have survived approximately 60 years of nuclear deterrence without the use of any nuclear weapons in warfare, much less a full-scale exchange. Similarly, 0.1 percent per year seems too low because that would imply that current policies could be continued for approximately 1,000 years before civilization would be expected to be destroyed. Over that time period, and subject to the above caveat about the risk changing over time, I extrapolate from past events and estimate that we would expect on the order of ten major crises comparable to Cuba 1962; 100 lesser crises comparable to the 1995-1996 Taiwan Straits Crisis, the 2008 Russo-Georgian War, or the ongoing conflict in Ukraine that started in 2014; plus a large number of other events that could lead to nuclear threats and therefore, potentially, to nuclear use.

If you agree with my reasoning that the risk of a full-scale nuclear war is less than ten percent per year but greater than 0.1 percent per year, that leaves one percent per year as the order of magnitude estimate, meaning that it is only accurate to within a factor of ten. For related reasons, that one percent per year estimate really spans a range from roughly 0.3 to three percent per year.

A risk of one percent per year would accumulate to worse-than-even odds over the lifetime of a child born today. Even if someone were to estimate that the lower bound should be 0.1 percent per year, that would be unacceptably high—that child would have an almost ten percent risk of experiencing nuclear devastation over his or her lifetime.

The above arguments show the importance of not only estimating the risk of a full-scale nuclear war, but also establishing a maximum acceptable level for that risk. If someone argues that 0.1 percent per year or some other value is an acceptable level of risk, society can then judge whether or not it agrees.

This quantitative approach avoids the ambiguity of non-quantitative arguments such as Schlesinger’s and McNamara’s. When the risk is highly uncertain, how do you determine who’s right? A quantitative approach, even to an order of magnitude as done here, requires both proponents and opponents of nuclear deterrence to justify their positions in ways that others can more easily decide who to believe.

I hope you will agree with either my quantitative approach or Vint’s qualitative approach, both of which conclude that the risk of a nuclear war is unacceptably high and risk reduction measures are urgently needed. For those who accept neither of our approaches, I have two questions:

First, what evidence supports the belief that the risk of nuclear deterrence failing is currently at an acceptable level?

Second, can we responsibly bet humanity’s existence on a strategy for which the risk of failure is totally unknown?

vs.

Qualitative

Vinton Cerf

VP and Chief Internet Evangelist, Google

Numbers are not needed for people to see the unacceptable risk we face.

.

Although I am not an expert on nuclear conflict, my good friend, Martin Hellman, has drawn me into a serious discussion about the risk of nuclear war. Along with Robert Kahn, I am the co-inventor of the Internet’s architecture and core protocols. I would prefer for humanity to endure and not obliterate itself. Both Hellman and I consider nuclear deterrence—threatening to destroy civilization in an effort to preserve the peace—to be untenable as a long-run strategy. But we differ on the need to quantify the risk of deterrence failing. In these two companion articles, we explain our different thinking.

I prefer a qualitative approach because most people relate to it better. Many are confused by mathematical arguments. While numbers do not lie, some human beings do. Quantitative estimates run either the real or perceived risk of being twisted to support whatever conclusion is desired.

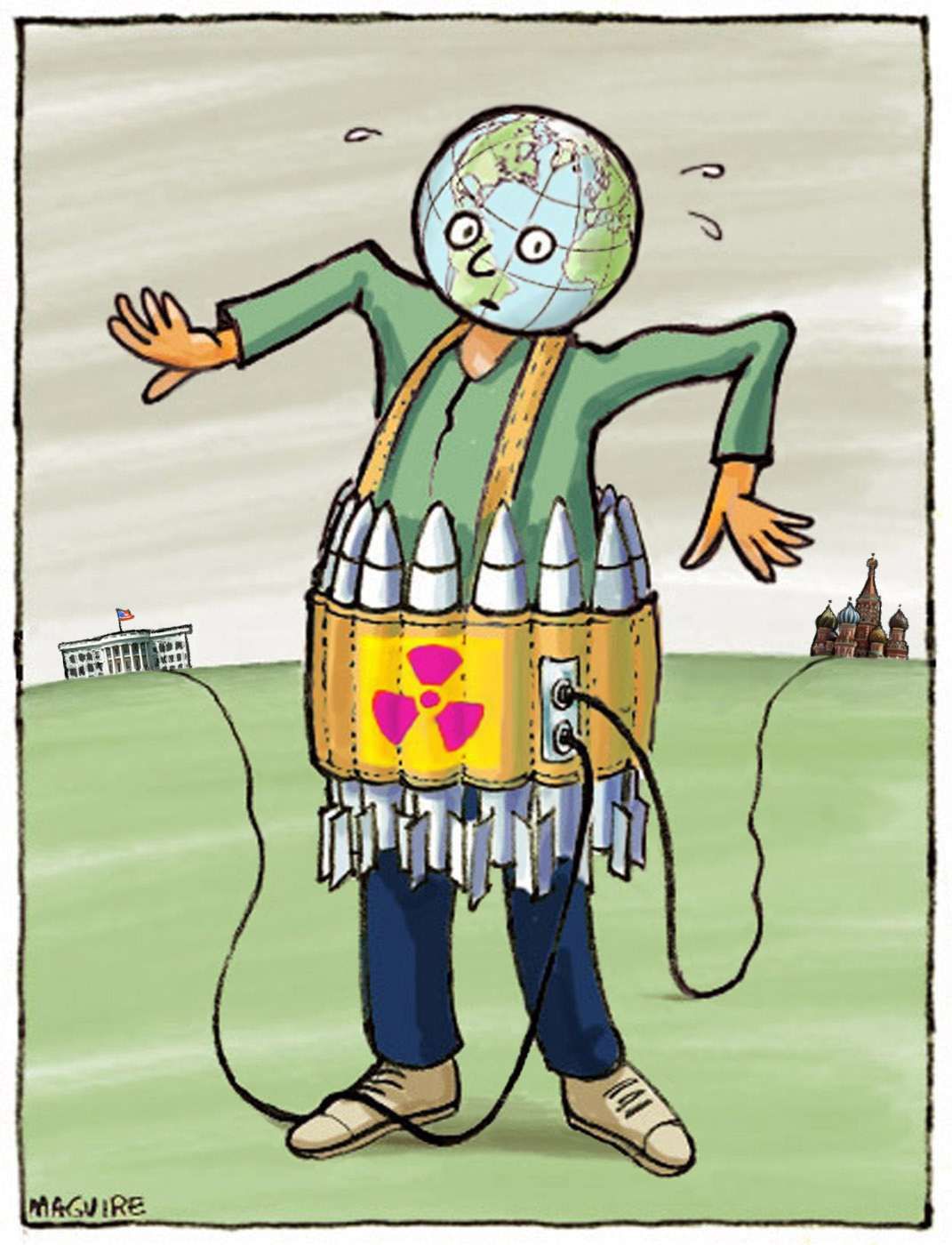

Instead, I prefer to rely on qualitative arguments like one that Marty has devised: Imagine that a man wearing a TNT vest were to sit down next to you and tell you that he wasn’t a suicide bomber. Rather, there are two buttons for setting off his explosive vest. One was in the White House with Trump for the last four years, and recently was given to Biden. The other is with Putin in Moscow. You’d still get away as fast as you can! Why, then, has society “sat here” for decades assuming that, just because the Earth’s explosive vest has not yet gone off, it never will? A qualitative argument like that will convince far more people than any mathematical reasoning.

But, most fundamentally, I prefer a qualitative approach because there are too many examples of sheer luck averting the use of nuclear weapons. Numbers are not needed for people to see the unacceptable risk we face.

As one example, during the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, American destroyers attacked three Soviet submarines near Cuba and forced them to surface. No American, not even President Kennedy or his military advisors, knew that each of those submarines carried a nuclear torpedo. According to an officer on one of those submarines, its captain gave orders to arm the nuclear torpedo, but was talked down. The captain’s order makes more sense when one remembers that the last he had heard before submerging was that World War III seemed imminent; he was under attack; and surfacing would be a humiliating defeat. Fortunately, luck won out: the captain suffered humiliation, but civilization was not devastated.

Some may object that such Cold War incidents should not be used as guides in today’s very different world. Yet, in June 1999, at the start of NATO’s peacekeeping mission in Kosovo, an American general gave orders that his British subordinate feared was extremely dangerous. Their memoirs agree that a heated argument ensued, which ended with the British general telling the American, “Sir, I’m not starting World War III for you.”

More recently, on January 13, 2018, Hawaiians received the following emergency alert: “BALLISTIC MISSILE THREAT INBOUND TO HAWAII. SEEK IMMEDIATE SHELTER. THIS IS NOT A DRILL.” Fortunately, it was a false alarm and did not cause a response that might have been misinterpreted by our adversaries.

As of September 2020, it is estimated that there are 13,410 nuclear weapons in the world, with 91 percent of those divided between the United States and Russia. Speaking purely qualitatively, I see no scenario in which so many weapons are needed, even under the theory of Mutually Assured Destruction or MAD.

Marty argues that risk reduction efforts will languish until the risk of nuclear war is shown to be clearly unacceptable. Society’s lack of action, or even concern, might seem to justify his thinking. But, even if a study were to produce an unacceptably high numerical risk value, some would still dispute the numbers or find them unintuitive.

As I read Marty’s analyses, I am struck by the thought that any positive risk of a global nuclear exchange is simply unacceptable. The mere existence of nuclear weapons and the possibility that their availability might lead to their use seems self-defeating. As Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev stated, “a nuclear war must never be fought and cannot be won."

We would do well to ask ourselves how we might accomplish risk reduction regardless of the quantified risk. If sufficient people desire risk reduction, regardless of their agreement or disagreement as to its quantification, we might succeed in making the world a safer place. Is there any other logical course of action?

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: nuclear arms control, nuclear deterrence, nuclear risk, nuclear security, nuclear weapons

Topics: Nuclear Risk

Share: [addthis tool="addthis_inline_share_toolbox"]

I especially appreciated the analogy of someone sitting next to me with a TNT vest. I would however argue that one’s sense of danger is irrelevant simply because there is no way to escape. People understand power and powerlessness with apathy and denial if not outright depression as the common response. What I think is missing in both arguments is the economic aspect of nuclear deterrence. I think of a man standing atop a mountain of gold telling others “this is my gold, if you touch it I will kill you”. …or perhaps worse, “I would rather blow up my… Read more »

13,410 nuclear weapons 91% divided between US and Russia surely is incorrect. ROW has only about 100 weapons ? Would that be true !

Your math is off. 99.3% would give you your approximate 100 weapons for ROW

Neither mentions the fallacy in the MAD concept. Two simultaneous events aren’t necessarily causally linked. There’s no compelling reason to believe that the possibilty of mutually assured destruction has been the causal factor preventing an event that hasn’t happened.

MAD was never the reason for not having a Nuclear exchange, MAU (Mutual Assured Uncertainty) was/is the reason. No sane person/government will launch nuclear missiles if they realize there is no assurance that they would “win” or even survive; however, an insane person/government might and even a sane one who thinks it knows with a high degree of certainty that the outcome would be to their advantage.

Apart from the obvious nuclear risk. You have the legacy of 70 years of Cold War. The Hanford SuperFund site alone has tonnes of plutonium with half life of 24,000 years. There is also the added risk of detracting from such “””mundane””” items such as pandemics and global climate change not to mention that we are currently in the anthropocene era of our time on earth. I believe these factors raise the risks considerably. This problem is much deeper than meets the eyes. All governments on earth should be getting rid of nuclear weapons so fast that it would make… Read more »

Thanks so much for sharing your thoughts and calculations about the danger of nuclear war. I’m a playwright, and I’ve just written a play about much the same thing – so the qualitative approach resonated with me – but the more ways we can attract attention to this, the more hope of averting disaster!

President Kennedy said that man must make an end of war or war will make an end of man.

The scenario used for both viewpoints is the Russia/America nuclear standoff now nearing a century of aggressive sabre rattling. The designs of nuclear arsenals of both countries date from as far back as the 1970’s. Dr. Theodore Taylor listed several new nuclear weapons designs that had not been tried at that time in his Scientific American article April 1987. Reading that will clearly tell people they are vastly underestimating nuclear weapon capabilities and possible war time usage. Worse yet all the discussions leave out the devastation an insignificant nuclear power such as DPRK can accomplish.

I agree the newer breed of nuclear weapons and attitudes about low yield “field usable” nuclear weapons is something to be deeply concerned about. I am less worried about a traditional strategic exchange than I am about the potential for low yield nuclear weapons being excluded from MAD by political/military leaders who believe they can be safely and effectively used in place of less convincing conventional weapons. I think the concept of small scale limited nuclear conflict is insane. Having all who possess nuclear weapons believe completely in the doctrine of mutually assured destruction is essential to our global safety.

This. I don’t think either argument is convincing, because I don’t think the first nuclear war will be all-out. A limited exchange of low yield weapons that doesn’t escalate, but also doesn’t end in victory for either “side” is more probable.

Many people think that’s insane:. Killing people for any reason is insane and it happens every day….

My first guess is how easy is it for human error to start a nuclear exchange. Secondly how bad will the coming struggle for resources become. We will soon know. I believe we should have far more concern over water. That struggle will be widespread, and on us currently.

In reality, there are both quantitative and qualitative aspects to this discussion, that are both a priori and empirical in nature. From the quantitative, we may adduce that the time frame of non-use of nuclear weapons in inverse ratio to the reduction of actual weapons from its peak of plus 70,000 down to 13,000, does not necessarily represent a significant odds-reduction of risk, and particularly since the caliber of the power of the weapons themselves have increased up to 5,000x, or more, the power of the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Also, the prospect of a detonation near a… Read more »

I will go with Vinton G. Cerf, his qualitative argument resonates quite well with me. But we must also remember that the U.N. was partly created to facilitate the peaceful resolution of conflicts if not actually to ban wars totally. Yet despite and, at times, because of the U.N.S.C.’s unjust stances, nations march to war. Similarly, the objective of NPT is to prevent the proliferation of nuclear weapons and, theoratically, ultimately move towards nuclear disarmament. But despite the best of intentions to adhere to these objectives, including via multi-laterally negotiated pacts, the sudden debut of leaders with Trumpian ideosyncracies easily… Read more »