Why choose a career in art over nuclear policy? The money

By Molly Hurley | May 6, 2021

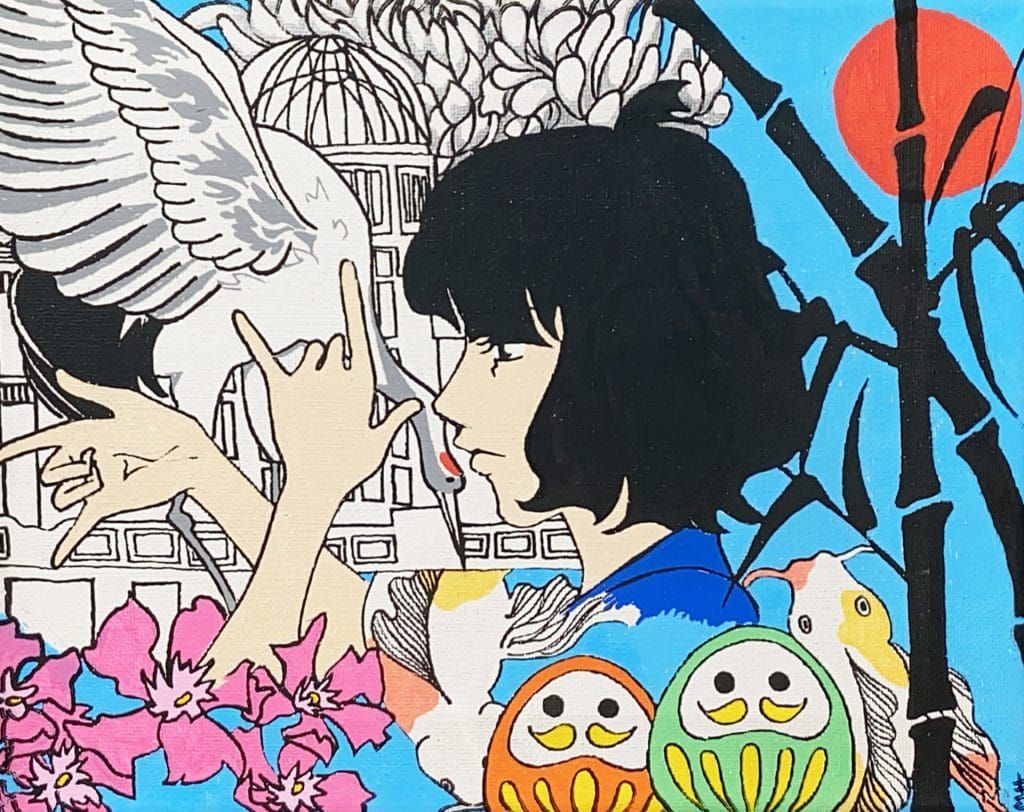

"Atomic Galaxy" by Molly Hurley (acrylic on canvas). The central figure in this painting is based on the Japanese novel series Youjouhan Shinwa Taikei (Tatami Galaxy), a story that explores existentialism. She is surrounded by Japanese symbols, including the dome that remained standing after the bombing in Hiroshima and the first vegetation (oleanders) that grew back after the bombing.

"Atomic Galaxy" by Molly Hurley (acrylic on canvas). The central figure in this painting is based on the Japanese novel series Youjouhan Shinwa Taikei (Tatami Galaxy), a story that explores existentialism. She is surrounded by Japanese symbols, including the dome that remained standing after the bombing in Hiroshima and the first vegetation (oleanders) that grew back after the bombing.

“Giving up those big bucks in policy to work in art instead?”

“So I guess you want to be a starving artist, huh?”

“Couldn’t you choose a career that’s a bit more lucrative?”

“You know, your parents can’t support you forever.”

“I guess that’s an all-right career path, but you should have a backup plan just in case.”

These are all responses I’ve heard over my lifetime when I have mentioned the idea of pursuing art as a career, or even just studying art. Now replace “art” with “nuclear policy.” You might not see an immediate connection, but, trust me, every young or early-career professional in my field knows what I’m saying.

Pursuing a career as a nuclear weapons policy analyst is no easier than trying to make it in the arts. In fact, becoming an artist might actually be the smarter career choice.

The working world. Since entering the arena to fight against nuclear weapons and nuclear annihilation, I can’t say I have any greater sense of job security about my near future than when I think about trying to pursue art as more than just a hobby. Sure, working as an independent artist doesn’t bring a steady, secure income, but unpaid internships in the nuclear field typically bring no income. And yes, art school can be exorbitantly expensive, but so can master’s programs in political science or international relations.

Let’s take a broad look at median annual income: Someone with an undergraduate degree in fine arts can expect to make about $40,000 a year, on average, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. A person with a public policy degree earns an average of about $45,000 a year. People working as independent artists, according to the bureau’s data from May 2020, make a mean annual wage of $65,020 a year. The federal government doesn’t have comparable data for a field as specific as nuclear policy, but I can speak anecdotally about what I’ve seen in the way of job and internship opportunities in this space—with the frustratingly common educational requirement of a master’s degree for “entry-level” positions.

Which leads me to point out some key differences between a career in art and a career in nuclear policy. It would be nearly, if not completely, impossible to make it as a policy analyst without any formal education. And often you can’t get far without an advanced degree like a master’s or PhD. In the art world, however, anything goes. Sure, there are plenty of artists who fit the “starving artist” stereotype, even famous ones like Vincent van Gogh, El Greco, and Johannes Vermeer. But there are others who do just fine for themselves, including some who are completely self-taught. For example, Jean-Michel Basquiat was expelled from an alternative high school and then kicked out of the house at age 17. Within 10 years, however, he was worth an estimated $10 million. Ai Weiwei dropped out of art school to draw street portraits and worked multiple jobs to make a living in his early years. He is now estimated to be worth $15 million. And Yoko Ono, who only studied music formally, is worth $700 million as a visual artist.

Art also seems to matter more to most people than nuclear weapons do. Walk around Central Park in New York City, and you’ll probably run into at least a few caricature artists, maybe some sidewalk chalk artists, and others working in a variety of mediums. Driving around the artsy neighborhood of Montrose in Houston, while I was in college there, I saw many of the graffiti works used as Instagram backgrounds in my friends’ posts. But try to talk about how important re-entering the Iran deal is, or how dangerous nuclear weapons are, on the street? People might think you’re recruiting for a cult preaching apocalypse.

A funding shortfall. Unfortunately, nuclear weapons aren’t high on most people’s priority list of things to deal with today. This lack of attention also means a lack of funding, hence a lack of positions and a lack of that sweet cash to pay to your overworked interns. Yeah, we get it. But how else are young people or people of color supposed to enter this field? I hear all the time how much the nuclear nonproliferation and disarmament space needs young people to bring diverse perspectives and fresh ideas (at Beyond the Bomb, we often refer to the nuclear space as being “pale, male, and stale”). Unfortunately, the barrier for entry into this field is not only educational but also economic.

In speaking with other early-career professionals, I have learned that workplaces have been getting marginally better over the last few years about paying their interns, but it’s still not great. And, as far as I can tell, it might continue to be “not great” with, for example, the MacArthur Foundation’s announcement that it will end its grant program focused on nuclear weapons issues in about three years. MacArthur pulling out of the space will be a huge blow to the funding sphere for nuclear weapons policy analysts. The foundation has given out $100.8 million between 2014 and 2020, or an average of $14.4 million per year.

MacArthur isn’t the only funder in the nuclear field. The Ploughshares Fund, for example, distributed $4.8 million in 2020 to projects focusing specifically on nuclear issues. According to a funding map from the Peace and Security Funders Group, 101 funders gave out a total of $121.7 million to 446 recipients last year for peace and security efforts.

Arts funding in the United States dwarfs what’s available for nuclear issues. A cursory glance at the size of available funding in arts shows that the National Endowment for the Arts alone allocated $162.25 million in 2020—more than all grant money available for nuclear security issues. And there are thousands of other grant makers for the arts. So, if we consider the amount of grant money available for art and for nuclear nonproliferation, maybe I really would make more money as a “starving artist.”

My message to employers in the nuclear field is this: I understand your frustrations with the lack of funding for our cause. I currently work for a foundation that tries to provide a little bit of that money to your organizations, and it does indeed pain us to have to turn people away. But if my “starving artist” art professor at Rice University can offer me $20 an hour to buy her more paint, or drive her new works to a gallery, then I should be able to make at least minimum wage studying the intricacies of US-China relations and their nuclear weapons policies at your think tank (but maybe we can aim a little higher than that).

If I happen to find myself with no other options and two mouths to feed (including my dog), perhaps my last resorts are to become either an Instagram influencer through my artwork or a Greta Thunberg-type activist for nuclear disarmament. Now if only this crusty, old 25-year-old can figure out TikTok (*winkwink*).

In all seriousness, though, I’m too deep into this nuclear stuff to abandon it now. While I found out, after enrolling in a graduate-level international relations class at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln this last semester, that IR is not for me, incorporating political themes into my drawings is.

The best of both worlds. I’ve been drawing for as long as I can remember—even before I knew how to write my name or tie my shoes. A lifetime of artmaking, yet I never gave my creative side a second glance until recently, due to the pervasive assumption that pursuing art equals living in poverty. I defaulted to pursuing a more “practical” career than artmaking, earning my Bachelor of Science in chemistry. While I adore chemistry, especially organic chemistry, and I have no regrets about choosing to study that field, I do regret not giving my artwork its due consideration in the past. Clearly my life has taken a few unexpected twists and turns, since I now find myself working in the nuclear weapons policy and social advocacy space, but one thing has remained constant through it all—through the MD-PhD aspirations, the theoretical chemistry lab, the organic chemistry research lab, the law school entrance exam, and the nuclear policy analysis: I always come back to art.

“Only the truly gifted can make it as an artist” is what I always thought. Who defines which artists are “gifted,” though? We all have stories to tell, and I’ve discovered this year that one of my favorite ways to tell mine is through illustration. I haven’t stopped at just my story, though. I’ve been slowly working to hone my skills as an artist so I can facilitate sharing the stories of others too, particularly the stories of those most directly affected by nuclear weapons issues and history. And a career combining the visual arts with nuclear policy may not be as farfetched as one might assume.

Lovely Umayam is a writer, nuclear nonproliferation expert, and nonresident fellow at the Stimson Center, where she is researching technologies like blockchain—but also the founder of Bombshelltoe Policy and Arts Collective. A single glance at her project Illuminating Radioactivity can show you, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that she knows what she’s talking about when it comes to nuclear weapons and she can do it in a way that is aesthetically satisfying. I’m also encouraged by the Arts Science Initiative here at the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, which most recently sponsored a project called Amnesia Atomica by Mexican artist Pedro Reyes.

So there seems to be some hope I could forge my own career path at the intersection of art and policy. It’s hard to say what kind of yearly income this would bring, but I could always fall back on drawing portraits in Central Park.

Whether I choose nuclear policy or art, hell maybe even both, one thing will remain unchanged: My mother will never truly understand what exactly it is that I do.

Editor’s note: This story has been corrected. The MacArthur Foundation is leaving the nuclear field in about three years, rather than five.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: art and science

Topics: Nuclear Risk, Nuclear Weapons, Opinion, Voices of Tomorrow

Great article. As you mentioned, why not combine both–art and activism? The best of both worlds, I would think.