Illustration by Erik English / Thomas Gaulkin

How to not die from heat on a too-hot planet

By Jessica McKenzie | July 21, 2022

Glen Kenny usually knows when someone is about to succumb to heat. He’s seen it a thousand times.

Workers may become less responsive than usual. They might struggle to stay focused on the task at hand, or forget to follow safety protocols. They might be short-tempered or aggressive when someone interrupts them. They might tell someone to back off, to leave them alone.

“Their body is under stress,” says Kenny, a professor of physiology at the University of Ottawa who studies the human heat stress response. “And for them, any voices, any distraction, that takes away their focus on themselves becomes an irritation for them. So you’re going to see irritability, you’re going to see loss of awareness of their surroundings, an inability to communicate effectively, all these become critical signs.”

The scary thing is, by the time an individual starts to feel unwell, they are already in the danger zone. Unlike strenuous exercise, heat stress is gradual. It builds, often without the individual noticing it—until all of a sudden, he or she does.

“It’s like a light switch,” Kenny says. "Suddenly, now their world collapses, their world has changed. Now they start to feel unwell. And that’s when, if they’re alone, and they don’t have the support system with them, they can’t manage it.”

“It’s like a light switch. Suddenly, now their world collapses, their world has changed.”

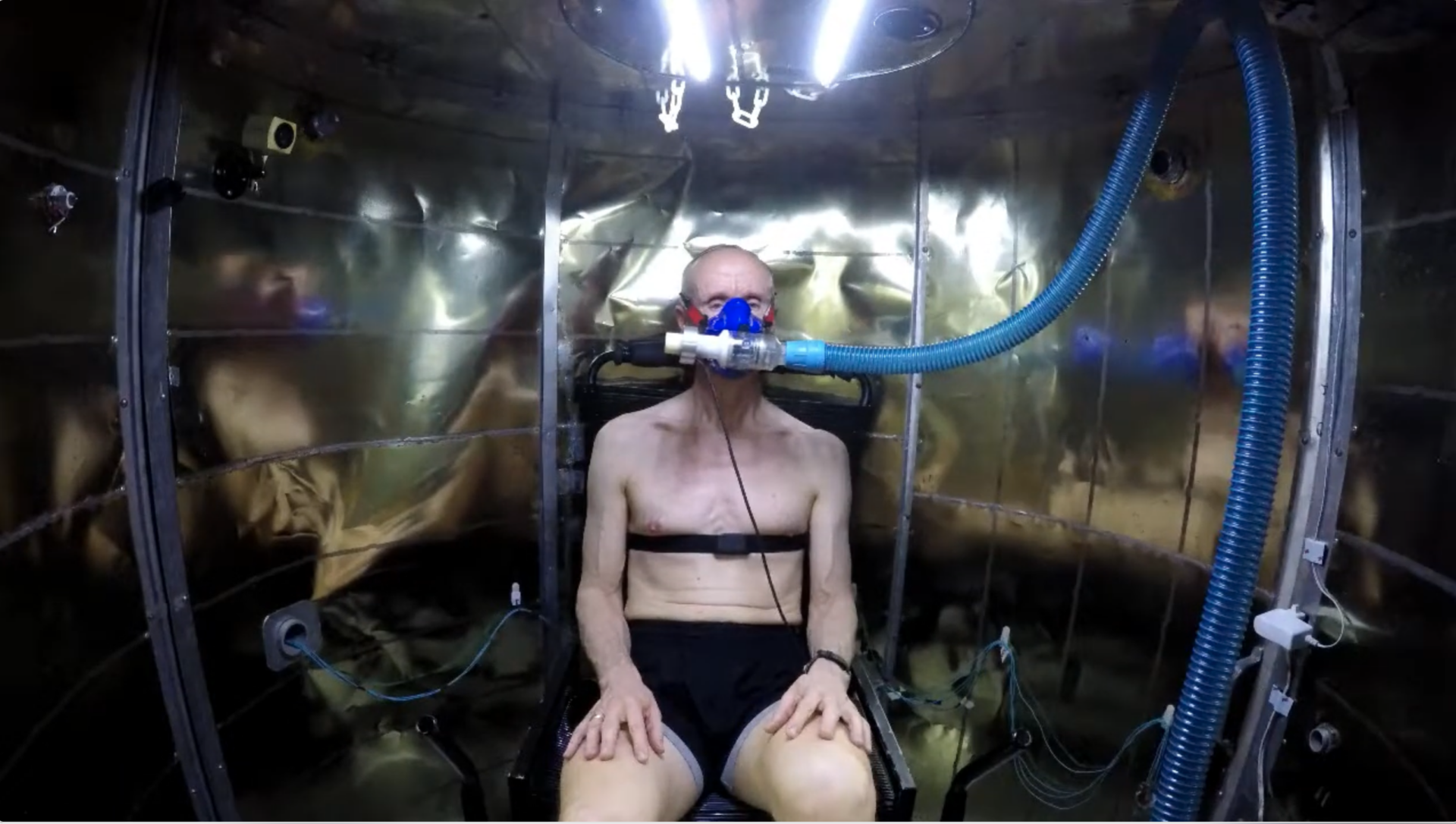

Kenny’s lab is the only one in the world to have an air calorimeter, a $6 million, state-of-the-art tool that can precisely measure the heat dissipated by the human body.

"It measures just how much heat you’re losing through evaporative heat loss and through dry heat exchange with the environment,” Kenny explains. “By measuring how much heat your body is producing, and how much it loses, you can measure very precisely how hot the human body gets.”

At any one time, Kenny says the lab could have 25 different trials running. They study how different characteristics—age, disease, sex, fitness, hydration, acclimatization—impact individuals’ ability to dissipate heat, and how bodies respond to heat stress. The goal is to establish more precise exposure limits, for workers and everyone else.

Blood and sweat. The human body has three to four million sweat glands and miles of skin blood vessels. When it starts to get hot, the body sheds heat by sweating and by increasing skin blood flow to increase dry heat exchange with the air. This happens when the body is working hard—during vigorous exercise, for example.

But when the air is hotter than the body, the body can no longer shed heat through dry heat exchange, and it has to sweat more to compensate.

“When you produce sweat, that means you’re stealing away from blood volume,” says Kenny. “That means the heart has to work harder to pump less of that blood unless you continuously hydrate.”

“It’s a big stress on the heart,” Kenny says. “The heart—it’s your pump, it has to maintain blood flow to the skin. That’s how you get rid of heat from the inner core, to bring it out to the skin’s surface. So the heart has to pump pretty hard to try to maintain that. The problem is, it doesn’t do a good job of it.”

This is particularly true of older individuals. “Throughout your lifespan, there’s a gradual decay, your body is slowly decaying,” says Kenny. For every 10 years, an adult human loses about four percent of his or her capacity to dissipate heat. Women have a five percent lower capacity to reduce heat, simply because of how their skin vasculature and sweat glands function, Kenny says. Other health conditions also have a big impact; having type two diabetes, for example, reduces one’s capacity to dissipate heat by about 20 percent compared to a non-diabetic of the same age.

4%

Percentage of adult humans’ ability to dissipate heat that is lost every decade.

So—it’s hot. The body is sweating. The blood is getting thicker and the heart is working harder to pump a lower volume of blood. If the heart can’t keep up, blood pressure drops. Now someone is at risk of becoming dizzy and disoriented. She might fall. She is less equipped to take care of herself, to move to some place cooler, to stand in front of a fan, to drink enough water. It’s a dangerous situation, especially for people who live alone.

Last year, during the almost week-long heat dome event in the Pacific Northwest, 800 people died in British Columbia—619 of them from heat-related causes. Of those, 98 percent of heat-related deaths occurred indoors. Two-thirds of the victims were 70 or older. More than half lived alone.

98%

Percentage of heat-related deaths that occurred indoors during the June-July 2021 heat wave in the Pacific Northwest.

Who died in the 2021 Pacific Northwest heat wave?

Of 800 deaths in British Columbia from June 25 to July 1, 2021, the BC Coroners Service determined 691 were heat-related. Some key indicators of the circumstances of those who died there were presented in a report last month.

The danger of heat waves. Older (and very young) individuals have a decreased capacity to shed heat. But Kenny says that any individual will be less equipped to handle the heat on, for example, day five of a heat wave than he or she was on day one.

Take someone who is working outside during a heatwave—a farm worker perhaps. Kenny says that there is often an assumption that at the end of the day, the worker goes home, cools off, and comes back fully rested and recovered and ready for the exact same conditions as the day before. But not every worker will have access to air conditioning at home, and time outside of work is not necessarily inactive—workers may have kids, chores, other responsibilities. Even without factoring in activity outside of work, one evening is not enough time for the body to bounce back from exposure to intense heat.

“The next day, it's not necessarily true,” says Kenny. “In fact, they’ll see a deterioration over successive days. And the reason for that is simply that, like anything else, if you go out and exercise and you exercise successive days, you need appropriate recovery to regenerate your body.” The same is true of heat stress. “A worker on day one, so let’s say it’s Monday, by the end of the week, they’re not functioning the same way. They’ll actually store more heat.”

“You give them a false sense of security, but they’re going back home as heat stressed as their non-cool counterpart. Therein lies the problem.”

The human body needs more time to cool and recover than one might think. Cooling centers, for example, are a popular solution for helping people who don’t have home air conditioning. Kenny showed me a chart from a recent, still-unpublished study that compared two groups of elderly individuals who had been exposed to high heat for a long period of time. One group was given access to an air-conditioned environment for several hours before returning to the high-heat environment; the other stayed in high temperatures for the entire time period.

The chart showed the body temperature of members of a group that spent time in air conditioning decreasing temporarily—but within two hours of returning to the high heat environment, their bodies were as hot as their peers who hadn’t had access to air conditioning. In the air-conditioned environment, blood vessels at the surface of the skin constrict, reducing blood flow, which slows the dissipation of heat. So the skin cools, but the limbs and the core remain at an elevated temperature. As soon as the people leave the air conditioning, their body temperatures rises again very quickly.

Kenny says that in non-laboratory settings, that can be very dangerous. The individuals who had time to cool off felt better, even though their bodies were still hot and stressed. “The average person, they’re going to feel good. They’re going to think, ‘Hey, I’m feeling okay, I’ve been cool.’ They’re more likely to be a little more active, generate a little more heat. So you give them a false sense of security, but they’re going back to their home as heat stressed as their non-cool counterpart. Therein lies the problem.”

120 minutes

Time within which the body temperature of people leaving a cool environment reached that of people with no air conditioning.

Perception and risk awareness. Underestimating heat is a common problem, one that is only set to get worse as extreme heat events become more common and more prolonged.

“What I’m seeing in my field, and who I work with, is we’re not taking into account perception,” says Alisa Hass, a hazard climatologist who studies heat. “We are just saying, ‘oh, like it’s hot. And here’s your excessive heat warning. And here’s what you should do.’” But people aren’t necessarily internalizing or acting on those warnings.

“A lot of times what I’m hearing is just like, ‘I’m not at risk, it’s not that hot,’” she says. “We’ve done surveys with students, with adults, with teenagers, and we get that same thing over and over again: ‘I’m not at risk, I’m healthy, it doesn’t matter.’ And if we’re not taking precautions, obviously, you’re going to be at risk for heat, no matter how healthy you are.”

Hass says that her research has shown that during heat waves in places with hotter climates like Tennessee, people are less at risk of heat illness because they know how to stay cool. They are more prepared to take preventative measures to keep themselves safe than, for example, people from a cooler climate experiencing an unprecedented heat wave in their region.

But people in hotter climates are more exposed during normal summer heat because they perceive it as normal, so they're just going about with their lives. "That’s going to become a really big issue as our climate continues to warm,” Hass says, and hotter temperatures become the norm.

Maps of heat-related deaths identified in the last decade and projected for the end of the century in the worst-case climate change scenario. Heat-related mortality in hotter southern states is generally lower than in northern states. Source: D. Shindell, et al. (2020). “The effects of heat exposure on human mortality throughout the United States.” GeoHealth, 4. Maps by Thomas Gaulkin.

Cities are starting to take steps to minimize community risk to extreme heat; increasing tree cover and increasing artificial shade can help combat the urban heat island effect. Part of Hass’s work has involved giving teenagers and other community members sensors, so they can map heat in the city and in their homes, to better understand the microclimates from one neighborhood to the next, one room to another. Knowing where people are going to be experiencing the hottest temperatures is one of the first steps to combatting heat illness. Expanding access to air conditioning, either at cooling centers or through programs that provide free air conditioners to those in need, will be part of the solution. (Although, people still need to be able to afford the electricity to run the air conditioner.)

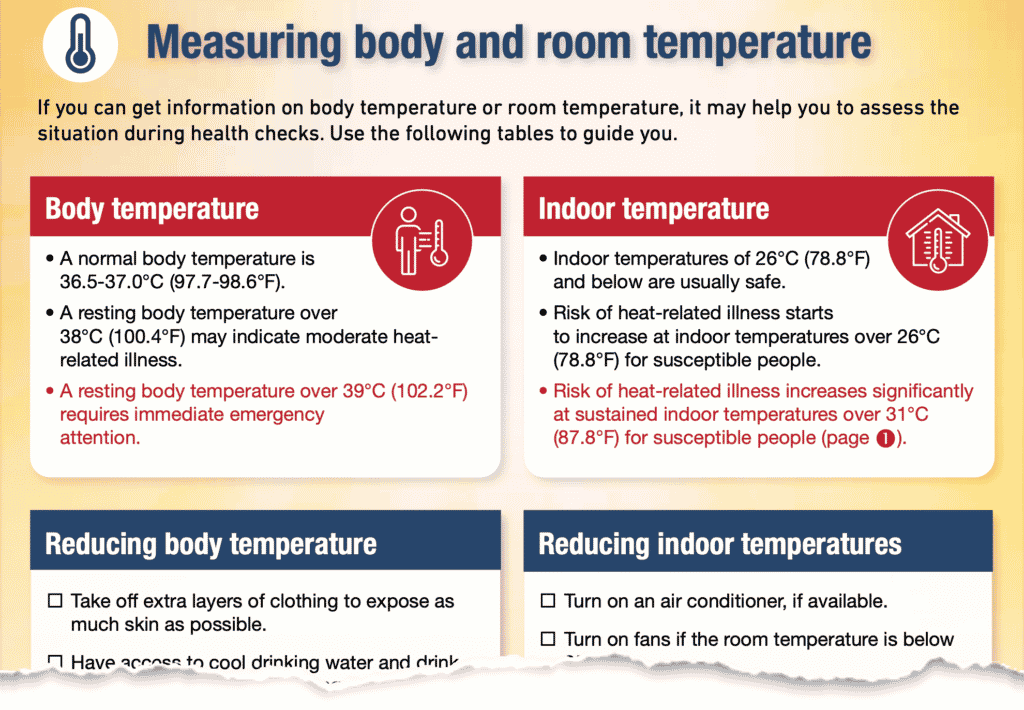

Education is a big part of preventing heat deaths. After the deadly heat dome event in British Columbia, Kenny helped develop a guide for recognizing and responding to the signs of heat illness: irritability, fatigue, headache, dizziness, rapid heart rate, and so on. There are simple and effective ways to combat and prevent heat illness: drinking lots of water, staying out of the sun, limiting movement. (In Kenny’s experience, drinking Gatorade and other electrolyte drinks can lead to gastric distress and diarrhea, especially in severe heat stress situations, so he recommends plain water and a healthy diet.)

Water is a more effective heat conductor than air, so taking a cool shower, or even better, a bath, is good way to lower one’s body temperature. Immersing someone in ice water is a fast and safe way to help someone in heat stress—the gold standard, Kenny says, although someone in severe heat stress should also get proper medical attention.

Not every piece of the solution is immediately recognizable as “combatting heat illness.” For example, Hass says, having good sidewalks in residential areas makes for tighter-knit communities. When communities are well-maintained and walkable, it makes it easier for people to connect with each other and to think, perhaps, “I haven’t seen my neighbor out with her dog recently, maybe I should go check on her?” Little things like that can potentially save a life.

So there’s at least some good news: Even in a rapidly warming world, heat deaths are not inevitable.

“Heat deaths are entirely preventable,” Hass says. “If we have the policies, if we have the means, if we have everybody prepared, they’re entirely preventable.”

As the Russian invasion of Ukraine shows, nuclear threats are real, present, and dangerous

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent, nonprofit media organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: air conditioning, cities and climate change, cooling, extreme heat, heat wave

Topics: Climate Change

Share: [addthis tool="addthis_inline_share_toolbox"]

Additional information on the role of humidity is needed here. Even less extreme heat (high 80s F) can be deadly with high humidity. Perhaps more likely than we expect.