Cyclone Daniel: A ‘natural’ disaster exacerbated by climate change and political instability

By Richard “Drew” Marcantonio, Jason Miklian | October 2, 2023

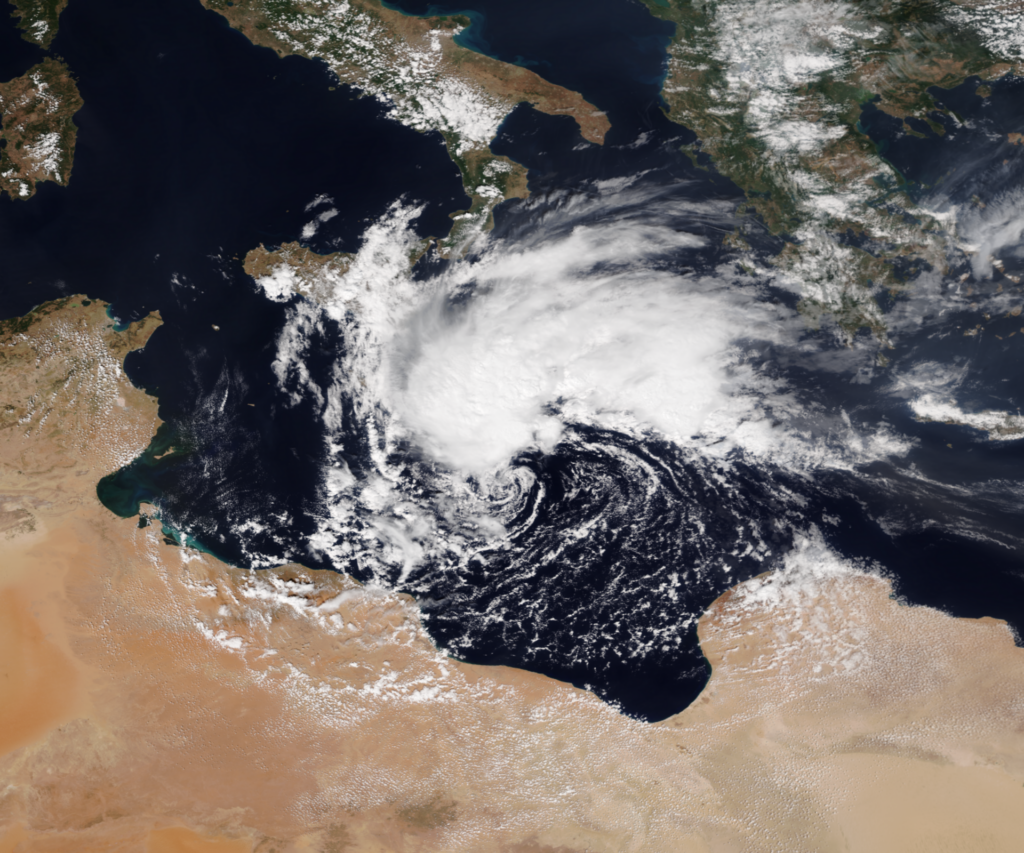

Libya was already one of the world’s most fragile countries when Daniel made landfall on September 10. Photo: NOAA

Libya was already one of the world’s most fragile countries when Daniel made landfall on September 10. Photo: NOAA

Cyclone Daniel may be the deadliest natural disaster in the Mediterranean’s history.

Daniel made landfall in Libya on September 10, after months of unrelenting drought. The storm’s intense rainfall fell on compacted soils too dry to absorb the water, and the rising floodwaters overwhelmed two dams above the coastal city of Derna. Estimates have shifted substantially in recent days, but at least 6,000 people have died and thousands more are missing, swept out to sea or buried under rubble and sediment. The before and after imagery shows a city buried and broken.

Libya was already one of the world’s most fragile countries when Daniel made landfall, devastated by decades of war. The European Union and the United States support the Government of National Unity, which holds the capital and western Libya, while Russia, Egypt, and the United Arab Emirates support the Libyan National Army in the countryside, which is aligned with the Government of National Stability in eastern Libya.

Half a century ago, the world found out what happens when a storm hits a fragile, divided country when a cyclone smashed into the coast of what is now Bangladesh. Hundreds of thousands of people died from the Great Bhola Cyclone after it inundated the world’s largest river delta. It was the deadliest storm in human history.

Bhola made landfall at a critical point of political and social instability. Pakistan was a divided nation, with the capital in Islamabad to the west of India, and an entirely separate Bengali-speaking part 1,000 miles away called East Pakistan. The country was split by two visions of its future, with constant tensions and protests. After the storm, then-president Yahya Khan’s feeble, uncaring aid effort magnified the death toll and spurred citizens to riot. To quell the uprising, Khan ordered a pogrom that killed up to 3 million more.

Bhola hit during the height of the Cold War. The United States aligned with Pakistan then, while the Soviet Union backed India. India smuggled Soviet arms to the Bengali rebels to stop the genocide. In response, the United States sent nuclear-armed naval destroyers into the Bay of Bengal. The Soviets escalated by calling in their first-strike nuclear submarines. Wanting to be seen as “coming off like men,” President Richard Nixon and his national security advisor Henry Kissinger debated starting a nuclear war to take out the threat, a “final showdown.” The world narrowly averted nuclear Armageddon because East Pakistan fell that week to the rebels—an event that birthed Bangladesh.

This entire chain reaction started with a storm. And with climate change already fueling increasingly powerful storms in increasingly unpredictable places, Bhola won’t remain a lesson from the distant past: It may be a harbinger of our future.

The parallels to Libya are disconcerting. In 2011, a civil war sparked by the toppling of former leader Moammar Gadhafi sent the country spiraling into chaos, and great powers took sides in the aftermath. One of the world’s poorest countries, Libya’s carousel of leaders neglected decaying infrastructure for years, even as they were warned of potential failures should the systems be stressed. As with Bhola, the storm slammed into a deeply fragile political situation. Both countries hosted inefficient and outdated warning systems that cost thousands of lives—deaths that could have been easily averted if the country’s leaders warned its citizens.

Perhaps the most damning parallel is that in the wake of disaster, aid efforts were expropriated by strongmen who wanted all of the credit (and money) for themselves. In Bhola’s case, Yahya spent the money on flying troops to East Pakistan and letting them sell the aid rations. After Daniel, former freedom fighter and CIA asset turned despot Khalifa Hifter is demanding that every penny of international relief pass through his fingers. Why does this matter? Because when disaster aid is used as a weapon of war, it inflames grievances from vulnerable populations, funnels aid money into weapons, and escalates tensions at an exceptionally fragile time. It is a recipe for new conflict.

Climate change further exacerbates Libya’s post-disaster stresses. Libya is the leading transit point of migration across the Mediterranean. Hundreds journey through Libya daily, primarily due to environmental strife driven by the same climatological shifts that contributed to the intensity of this event. The Mediterranean is now the deadliest border area in the world for migrants.

It is not yet clear how Daniel’s fallout will impact Libya’s stalemated conflict. In regions that are at high risk of conflict, extreme events like Daniel can be the spark that sends a country over the edge into outright war. Libya is also host to fragmented and diminished, but still present, Islamist militant groups, including Islamic State and Al-Qaida, which are both seeking an opportunity to resume a brutal war for control.

But of all of the lessons learned from failures of Bhola and other disasters, one key one that these events, while disastrous, can be transformed into an opportunity for environmental peacebuilding. If governments and humanitarian organizations respond appropriately to the resultant human crisis in a conflict-sensitive and intentional peacebuilding approach—for example as happened in the aftermath of the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami and the 2005 earthquake in Kashmir—there can be a chance for solidarity not only between erstwhile adversaries but also between the foreign countries that support opposing sides.

Daniel’s legacy may simply slide into the expanding morass of climate disasters around the globe. Death rates from extreme weather have decreased due to technological advances like early warning systems, but how long technology can outpace the socioecological effects of climate change is uncertain. Libya is also currently not a global focal point for climate and security fragility. But few thought it possible that East Pakistan could capture the world’s attention when Bhola hit, either.

In short, the problem isn’t just that each event is a roll of the dice for outcomes good or bad, but that due to climate change the dice are being rolled more often, in more places, every year. This recurrence can create cumulative vulnerability and stress that pushes social, economic, and political structures closer to the tipping point.

Humanitarian organizations are well versed in situations during which political factions attempt to weaponize aid. It can be tempting to let strongmen take a cut to ensure that the needy receive at least something. But in the most conflict-affected regions this can simply enable future violence, as seen in East Pakistan but also in other more recent settings like Sudan and Syria. Politicizing aid is a proven recipe for exacerbating disaster.

Aid organizations must ensure that humanitarian principles of neutrality, impartiality, and independence also take long-term consequences into consideration, especially when they risk creating conflict that spills out far beyond the disaster zone.

Moreover, it is necessary to look not just to Libya but other conflict hotspots equally vulnerable to climate disasters and act now to improve prevention and infrastructure to better reduce the likelihood and scale of conflict-triggering disasters in the first place. Climate-resilient infrastructure is one pathway that can better balance needs of the present while also better “future proofing” vulnerable communities ahead of disaster.

Anticipatory resilience efforts cannot protect unstable or conflict-ridden countries from all the effects of climate change, but they could limit the scope of climate-driven disasters and, perhaps, keep local catastrophes from metastasizing and enveloping entire regions in the kind of ill-governed misery now afflicting Libya.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Libya, climate crisis, cyclones, floods, infrastructure, resilience

Topics: Climate Change

John Pilger

1 second ago

Awaiting for approval

When I next speak to journalism students I will use this piece as a classic of its genre -burying Western culpability. In 2011, NATO led by the US, UK and France wilfully destroyed the modern state of Libya, bombing to death some 10,000 people. Maintenance of Derna’s dams was abandoned, along with other vital infrastructure. And you present it as a “civil war … spiraling into chaos”.

Shame.

Hi John, Absolutely agree that the original causes of the current conflict are worth specifically considering. This is especially true since it was led by many of the same countries that are most responsible for the hazard we chose to primarily focus on, anthropogenic climate change, and its intersection with human-constructed vulnerability. A rather rancorous irony. Thanks for the valuable feedback.