Oppenheimer’s second coming

By Gregory Kulacki | March 28, 2024

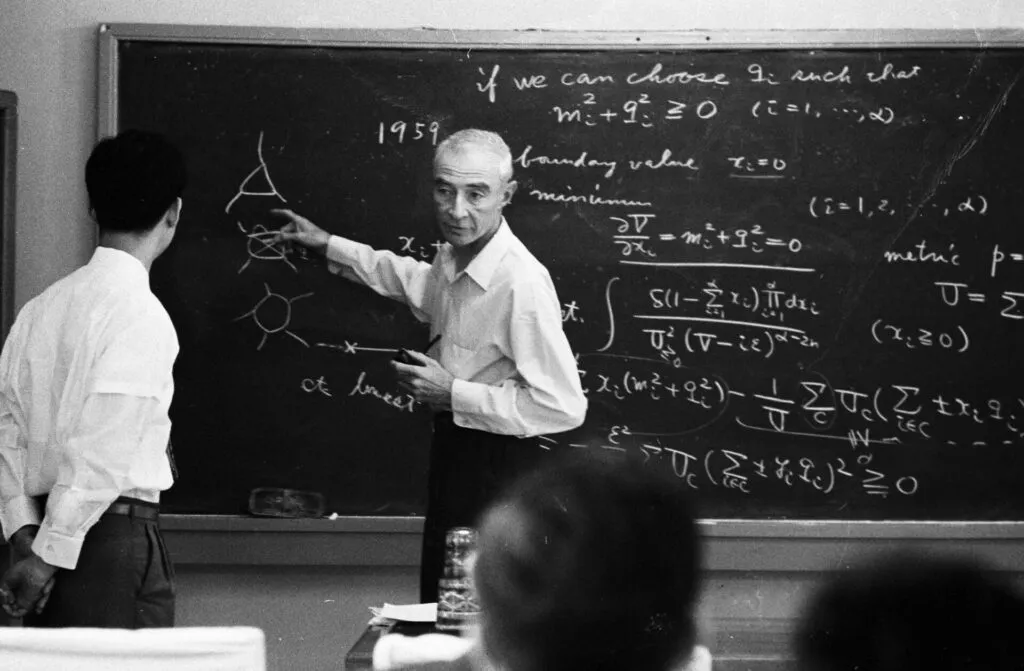

US theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer lectures at Kyoto University on September 14, 1960 in Kyoto, Japan. Christopher Nolan's biographical film about Oppenheimer opens on March 29, 2024 in Japan. (Credit: Photo by The Asahi Shimbun via Getty Images)

US theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer lectures at Kyoto University on September 14, 1960 in Kyoto, Japan. Christopher Nolan's biographical film about Oppenheimer opens on March 29, 2024 in Japan. (Credit: Photo by The Asahi Shimbun via Getty Images)

The world’s third largest movie market was curiously excluded from participating in the social, cultural, and economic excitement surrounding this award season’s most acclaimed product: director Christopher Nolan’s biographical film about physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer. That ended when Universal Pictures finally decided to release Oppenheimer to theaters in Japan.

The film’s local distributors declined requests for comment on the unusually long delay. It is reasonable to assume their patience was connected to concerns about how Japanese movie-goers might respond to a biopic about the “American Prometheus” who made the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki possible.

The film opens today in Japanese theaters.

Initial impressions. Estimating how many Japanese people were killed by the atomic bombs is difficult. The grotesque and inhumane effects on the dead and the survivors are painfully easy to see, especially in Japan. During the post-war US military occupation, military officers confiscated and destroyed images of the bombings and the survivors to inhibit public discussion in both countries. Nolan’s decision to talk about numbers but exclude images that would force viewers to witness the uniquely horrific pains inflicted on the bodies of the bombed can be justifiably criticized as an equally callous and calculated act of erasure.

Recent Japanese reviews of the film echo this concern. Gaku Tsutaja, a New York-based Japanese artist who explores questions about nuclear war in a recent exhibition in Japan, questioned whether the movie deserved its awards. Tsutaja told The Chugogu Shimbun, a Hiroshima-based newspaper, that Nolan’s is just another “white masculine” point of view that portrays Oppenheimer as the victim while neglecting the millions of Japanese bombed and the many Americans poisoned by the first atomic weapons. Yukio Kawana, another US-based Japanese artist and a third-generation survivor of the Hiroshima bombing, chose not to watch Oppenheimer because she felt Nolan failed to live up to the artist’s moral duty to tell his story “without reinstating trauma.”

A special preview and discussion sponsored by the Nagasaki Shimbun suggests audiences in Japan may be more forgiving.

Masao Tomonaga, a retired professor of medicine from the Atomic Bomb Disease Institute at Nagasaki University and an atomic bomb survivor himself, addressed the audience after the film. He was two years old when the plutonium bomb “Fat Man” obliterated his home on August 9, 1945. While Nolan’ s decision not to show images of the terrible aftermath “may be a weakness” of the film, Tomonaga said, it did convey the scientists’ sense of shock when confronted with humanitarian consequences. Kazuhiro Maeshima, a professor of global studies from Japan’s Sophia University, told the same audience: “The film was self-reflective and critical of the atomic bombings.” Maeshima, who earned his doctorate in government and politics from the University of Maryland, saw the movie as a positive sign of changing US attitudes.

Kawasaki Akira, an activist who won the Kiyoshi Tanimoto Peace Prize for his decades-long effort to bring stories told by the survivors to youth around the world, said it was “difficult to look at” the scene in which an emotionally disjointed Oppenheimer congratulates a cheering crowd of colleagues for successfully destroying Hiroshima. He felt that “painful” moment—together with the scene of the atomic scientists gasping at the horrific images of the bombings the audience was intentionally denied—artistically succeeded in compelling viewers to imagine the horrors the survivors experienced. Kawasaki encouraged everyone in Japan to go see the film: It is “a rare opportunity for ordinary people to think about nuclear weapons.”

Oppenheimer’s first visit to Japan. In the movie, US President Harry Truman asks Oppenheimer, rhetorically: “You think anyone in Hiroshima or Nagasaki gives a shit who built the bomb?” Contemporary Japanese interest in the answer to that question may determine whether the film enjoys the same critical and financial success in Japan that it has in the rest of the world.

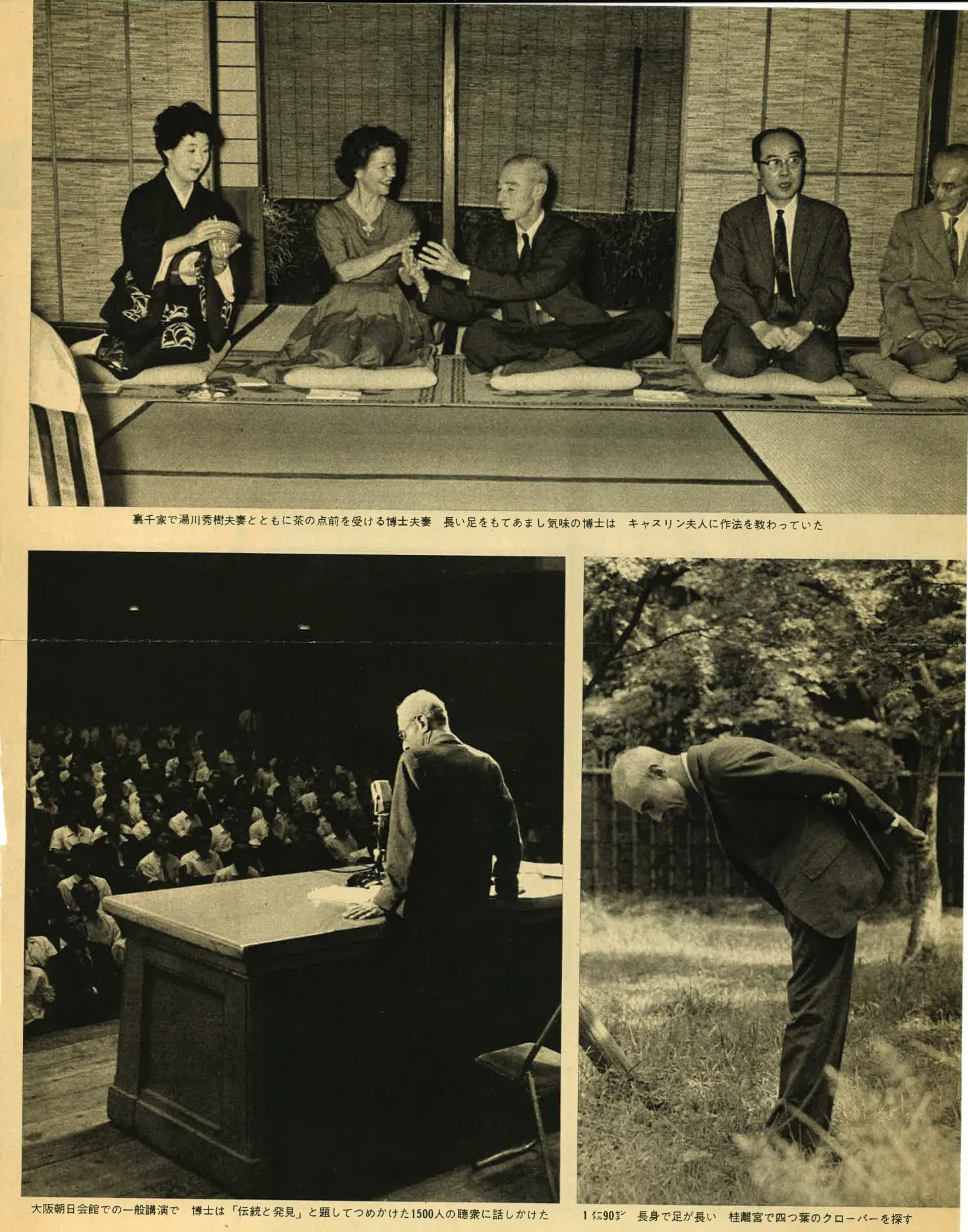

Japanese audiences were clearly interested in 1960, when Oppenheimer visited Japan as an honored guest of the Japan Committee for Intellectual Interchange.

The moment he arrived, Oppenheimer was greeted like a movie star with a barrage of lights and cameras. He spoke to packed public halls in Tokyo, Kyoto, and Osaka about the relationships between scientists, government, and civil society. But the Japanese organizers, fearing controversy, kept him away from Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Seven decades later, the distributors of the film in Japan seem to be adopting a similar approach in their marketing strategy: Images of the bomb have been stripped from the posters outside movie theaters and the trailers playing inside.

A Japanese reporter did manage to ask Oppenheimer in 1960 if he felt responsible for the suffering his work enabled. The enigmatic physicist answered that troubling question the same way Nolan does in his film. “I do not think coming to Japan changed my sense of anguish about my part in this whole piece of history,” he said. “Nor has it fully made me regret my responsibility for the technical success of the enterprise.”

Oppenheimer’s response seemed to help his hosts skirt the moral controversy inherent to inviting him to Japan. Maybe Nolan and the film distributors will be just as lucky in their apparent effort to keep uncomfortable discussions about Hiroshima and Nagasaki from undermining Japanese interest in the film.

During his visit, Oppenheimer was eager to impart some lessons he learned from directing the US atomic project. He told an elite gathering of Japanese scholars, artists, entrepreneurs, and officials organized by the International House in Tokyo that scientific discoveries, for good or ill, are inherently irreversible:

“There is a lot of talk about getting rid of atomic bombs. I like that talk; but we must not fool ourselves. The world is not going to be the same, no matter what we do with atomic bombs, because the knowledge of how to make them cannot be exorcized. It is there; and all our arrangements for living in a new age must bear in mind its omnipresent virtual presence, and the fact that one cannot change that.”

Earlier that same day, a young Harvard professor named Henry Kissinger, who spoke to the same International House community two days later, told the Tokyo press Japan needed tactical nuclear weapons to defend itself against a soon-to-be nuclear-armed communist China. At the time, the Eisenhower administration was making the same case to a resistant Japanese government and ramping up the numbers of “battlefield” nuclear weapons it deployed on US military bases on the island of Okinawa, which it refused to return to Japan. (The US military occupation on Okinawa only officially ended in 1971 under the Nixon administration.)

Long-term influence. The Pulitzer Prize winning biography that informed Nolan’s script claims Oppenheimer justified his post-war reluctance to build the hydrogen bomb by arguing “it would be both more economical and more effective militarily to accelerate the production of fissile materials for small, tactical nuclear weapons.”

The General Advisory Committee’s 1949 report at the center of Nolan’s drama, which purportedly documents that claim, is less definitive. But Oppenheimer’s comments on the bomb during his visit to Japan do make clear he was willing—and emotionally, intellectually, and morally able, despite his awareness of what happened to people in Hiroshima and Nagasaki—to continue to help the US government prepare to fight and win a nuclear war.

The cultural exchange program that brought Oppenheimer and Kissinger to Japan at a critical moment in the evolution of the security relationship between the two governments was funded by philanthropists from both countries. The intention of the program organizers was to create, through personal contact, a cross-cultural community of “leaders, creative artists and scholars” who could, according to an early International House report to the Rockefeller Foundation (its most important patron) “develop international mindedness, and frank off the record discussions on international affairs.” Nolan’s film may facilitate the same ends in a new critical moment for the US-Japan security relationship.

Suzuki Tatsujiro, a nuclear engineer with advanced degrees from Tokyo University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who served as the vice chair of the Japan Atomic Energy Commission and is the vice director of the Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition at Nagasaki University, appreciated Nolan’s investigation of “the social implications of scientific innovation and the relationship between scientists and politics.” At the same time, he was disappointed the movie “did not address the responsibility of the US government decision to drop the bomb” and “ignored the voices of victims.” Together with Kawasaki, Suzuki plans to organize post-screening discussions to further public debate about nuclear weapons and their consequences in Japan.

Kawasaki thinks the movie might broaden Japanese thinking about nuclear weapons. Everyone here learns about the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in school. But only a tiny percentage may know about Oppenheimer’s Jewish heritage or the US scientific race with Nazi Germany to develop the bomb. Kawasaki, however, wonders about the long-term impact of an expertly crafted American story about how and why “a powerful military nation like the United States organized scientists to build the bomb despite their moral reservations.” He worries some Japanese viewers may conclude their government needs to do the same because of a perceived threat from communist China.

No one can predict the social and political effects of influential cultural products and activities, like Nolan’s movie or the 1960 exchange program that brought Oppenheimer and Kissinger to Japan. It is difficult to hold artists and organizers responsible for the possible unintended consequences of their works. The Japan Committee for Intellectual Interchange probably did not anticipate the forum they created would one day be used to suggest it is foolish to hope for the abolition of nuclear weapons, or to make a case for using tactical nuclear weapons to defend Japan. Nolan, on the other hand, seems more self-aware about the likelihood his film might have a negative influence on the global public debate about the existential danger the bomb created.

A wake-up call? In an interview with the Bulletin published just before the film was released in the United States, Nolan confessed, “there’s a phase in which the more you know about nuclear weapons, you start to see them as more ordinary armaments.” He expressed concern about a general public acceptance Oppenheimer warned his audience in Tokyo they could not avoid. Nolan speculated the “nuclear Armageddon” his Oppenheimer imagines and conveys to Albert Einstein at the end of the movie is most likely to begin with “the use of tactical nukes leading to larger- and larger-scale conflict that will ultimately destroy the planet.”

There is a terrifyingly good chance that chain reaction will begin in East Asia. An isolated, impoverished North Korean dictator is practicing to launch his tactical nuclear weapons first to defeat powerful neighbors who despise his government and hold massive war games twice each year. South Korean and Japanese officials are lobbying willing US counterparts to get them US tactical nuclear weapons they can threaten to use first. China is building hundreds of new silos for the new nuclear-armed missiles it may place on hair-trigger alert. And the US military is practicing to respond to China’s silos by uploading stored nuclear warheads to existing US launchers as soon as the only remaining nuclear arms control agreement expires in February 2026.

Korea Diplomacy Plaza, Japan’s New Diplomacy Initiative, and the US-based Union of Concerned Scientists are jointly preparing to hold a second quadrilateral dialogue between scholars, scientists, and experts from South Korea, Japan, the United States, and China. The intent is to bring people together to create conditions that encourage their governments to act sensibly—just as it was for the cross-cultural non-governmental organization that brought Oppenheimer to Japan in 1960. There is hope, but no expectation, the release in Japan of Nolan’s award-winning film will too.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Perhaps graphic pictures of the aftermath of the bombings would have added to the movie, but as this article points out, Oppenheimer’s moral misgivings and guilt came across anyway. And if such images were used, then others could equally insist upon showing the Rape of Nanking, Pearl Harbor, the Bataan Death March, and Japan’s bio-labs with their victims. Humans may still blow themselves up, but the bottom line remains true, which is that although the bombs fell on Japan, the initial race was to beat Germany to them, and if that race had been lost, humanity would already have blown… Read more »

Let’s say the estimate of 500,000 American casualties was wrong by half. Are those lives lost in a conventional manner any less valuable than those at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, not to say he Japanese soldiers and civilians.The Japanese have a certain moral ambiguity which has turned them into the victims instead of the aggressor. To my knowledge the Japanese have never acknowledged their responsibility for the war in the Pacific.

The use of these weapons against vast civilian populations came after relentless firebombings all around Japan against civilian populations in numerous cities using conventional weapons. What is different about atomic weapons was the scale of their genocidal capabilities and reach. Indeed Japan also committed horrific atrocities through the war around Asia and the Pacific, but retaliation for these acts had already taken place on a grand scale by 1945, and then some, all throughout the Pacific and Asian theater. The nuclear weapon itself was truly a “destroyer of worlds”— and the survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki experienced this firsthand as… Read more »