Introduction—Russia: What to expect next?

By Dan Drollette Jr | November 9, 2022

Introduction—Russia: What to expect next?

By Dan Drollette Jr | November 9, 2022

In the weeks immediately following the signing of the Nazi-Soviet pact which led to the start of World War II, Winston Churchill famously said: “I cannot forecast to you the action of Russia. It is a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma…”

Churchill’s words are still quoted regularly whenever the topic of Russia comes up; pundits love to portray Russia as an inscrutable and menacing land that plays by its own rules.

But those same critics tend to forget the second half of Churchill’s famous comment: “… but perhaps there is a key. That key is Russian national interest.”

With that in mind, this special issue of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists explores some of the elements that make up the Russian national interest, whether it be Russia’s economy, the thinking of ordinary Russians, the vulnerabilities of its oligarchs, or Putin’s mindset concerning NATO and the West.

Crucially, this issue of the magazine goes into who and what is likely to follow, once Putin is gone. For at some point, every human being dies, and Putin will go away, sooner or later—which forms the basic premise of the piece titled “After Putin—What?” Written by Vladislav Zubok, a professor of international history at the London School of Economics and author of the book Collapse: The Fall of the Soviet Union, this essay raises the question of whether there are any realistic scenarios for what happens once Putin does depart the scene. Will this heavily armed superpower collapse after Putin? Or will Putin’s successor turn to the West with a plea for peace and engage the country in reforms and modernization? Or has Putin “baked in” an immutable course for the future, whoever happens to run the country after he is gone?

Which leads to the issue of whether the East and West are indeed simply picking up where they left off after the Berlin Wall came down in 1989—a common trope these days. In “Not your grandparents’ Cold War,” authors Joseph Tavares and Kori Schake—both of the American Enterprise Institute—examine whether the events in Ukraine do indeed mean that the Cold War is back. Especially as some basic underlying factors have changed dramatically since then, including China’s ascendance as an industrial superpower, the emergence of a much more tightly intertwined global economy, and US allies who are fundamentally much more economically advanced and militarily capable than they were during the Cold War—especially in the earliest years immediately after World War II, when Britain, France, and West Germany lay in ruins. In short, while history sometimes rhymes, it seldom repeats itself. Maybe some “lessons” from the Cold War should be re-examined.

Extending on this theme, author Brooke Harrington—a sociologist at Dartmouth College—argues that nowadays, the West has some new and unique tools at its command that were not available previously. In this era of Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook (in addition to the SWIFT electronic banking system and economic sanctions), the West can easily target the ultra-wealthy individuals who inhabit Putin’s inner circle—the oligarchs—with an unheralded and surprisingly effective tool: social stigma. In her essay, “Sanctioning Russia’s oligarchs—with shame,” Harrington argues that the very public nature of the seizing and freezing of the high-profile status symbols of Russian oligarchs, ranging from luxury yachts in the Cayman Islands to expensive villas in Italy—along with other social stigmas such as walkouts by members of the United Nations when the Russian foreign minister began to speak—have helped to begin the shattering of support by Russian elites for Putin’s regime. Social shaming, a tool known since at least Nathaniel Hawthorne’s publication of The Scarlet Letter, could be helping to make the first cracks appear in the brittle power structure that comprises Putin’s autocracy.

This special issue of the magazine also contains an interview with political scientist Francis Fukuyama, author of the 1990s best-selling book, The End of History and the Last Man. The book essentially argued that the struggle between ideologies was at an end, with the world settling on liberal democracy and the free market after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War. On the 30th anniversary of its publication, Fukuyama looks back, and tells how some of his thinking has evolved and changed since then—and in other key ways, stayed largely the same regarding certain key premises.

Among those key premises, Fukuyama says that in spite of President Vladimir Putin’s actions, the leader of Russia saw none of his fondest dreams—Ukraine being overwhelmed, neutral countries distancing themselves from NATO, Eastern Europe turning more autocratic—come to fruition. Indeed, the trend towards democracy has been continuing, when looked at on a long-term, global scale.

But we should not rest easy, warns Fukuyama, because other fake-populist, authoritarian wanna-bes are continuing to emerge around the globe—including in the United States.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

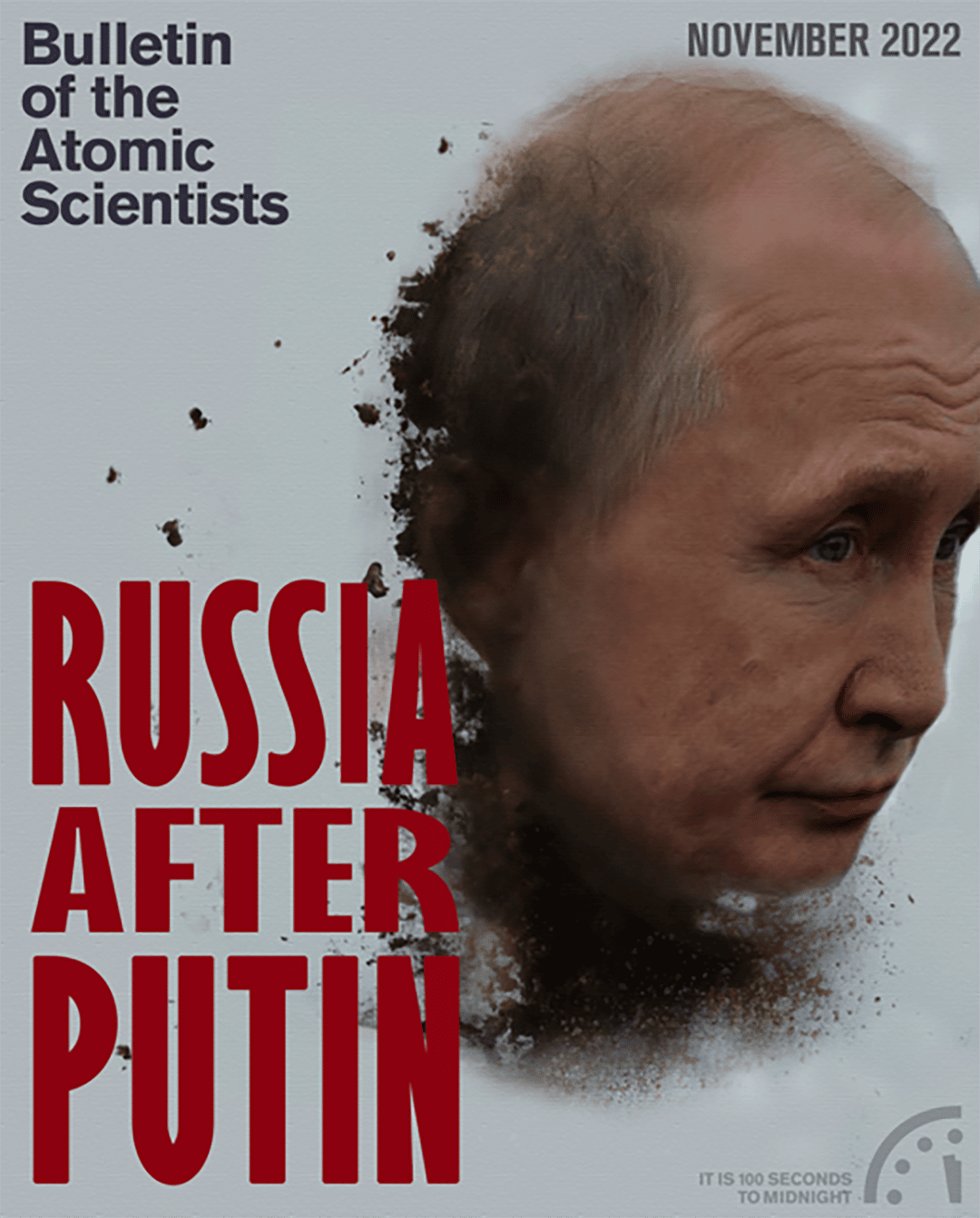

Regarding the photo of Putin in the email notification:

Is it Saint Putin? Or is it Satan Putin? Or to is it that, to paraphrase Churchill:

“Putin is not so devilish as he seems, nor as angelic!”