Abramson, A. 2021. “Substance Use During the Pandemic.” The Monitor 52 (2). https://www.apa.org/monitor/2021/03/ substance-use-pandemic

Allison, G. 2004. Nuclear Terrorism: The Ultimate Preventable Catastrophe. New York: Times Books.

Baldi, I., Lebailly, P., Mohammed-Brahim, B., Letenneur, L., Dartigues, J.-F., and Brochard, P. 2003. “Neurodegenerative Diseases and Exposure to Pesticides in the Elderly.” American Journal of Epidemiology157 (5): 409–414. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwf216

Bjørling-Poulsen, M., H. R. Andersen, and P. Grandjean. 2008. “Potential Developmental Neurotoxicity of Pesticides Used in Europe.” Environmental Health 7 (1):50. https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069X-7-50.

Block, M. L., and Calderón-Garcidueñas. 2009. “Air Pollution: Mechanisms of Neuroinflammation and CNS Disease.” Trends in Neuroscience 32 (9): 506–516.

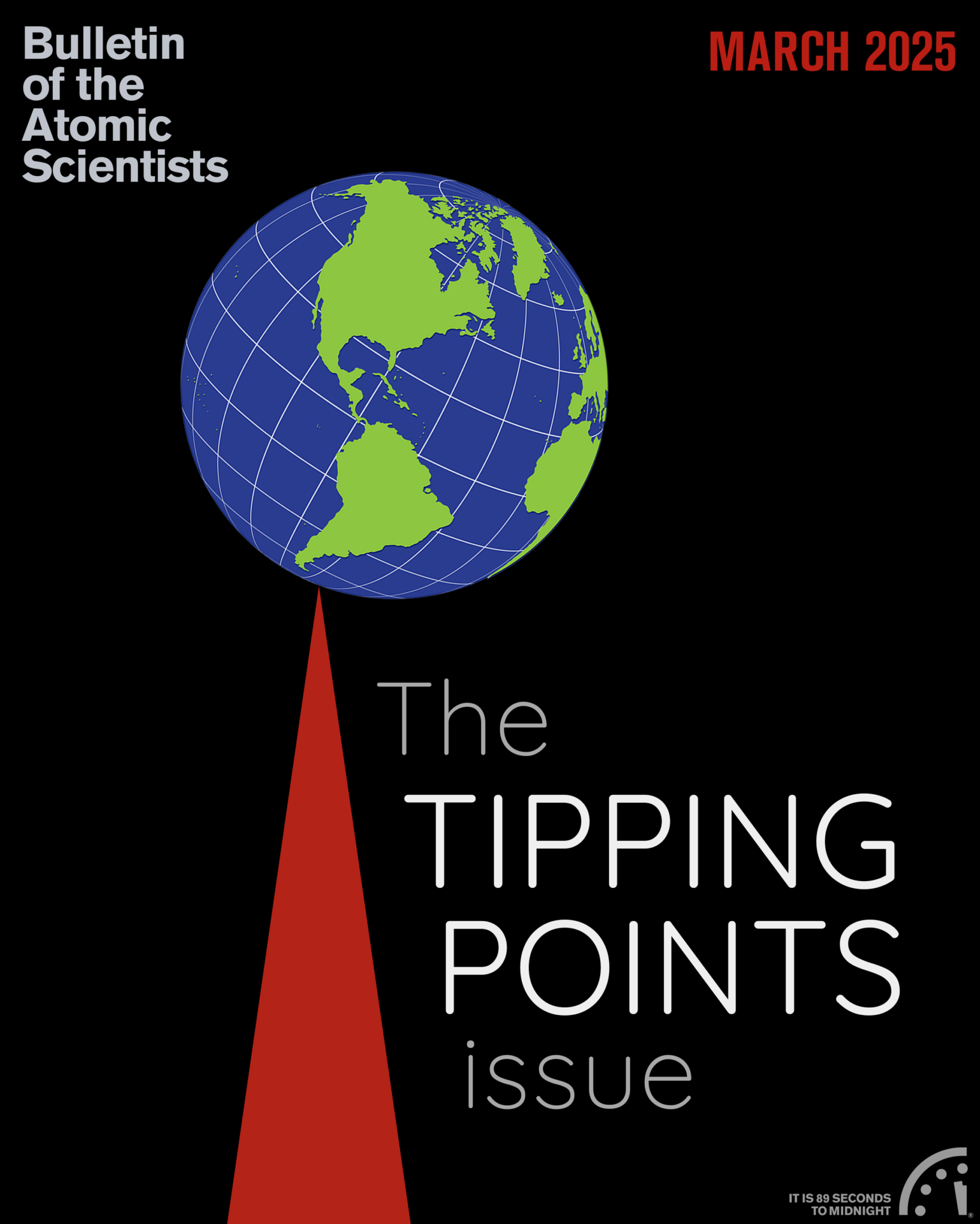

Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 2023a. “About the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.” https://thebulletin.org/about-us/

Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 2023b. “The Doomsday Clock: A Timeline of Conflict, Culture, and Change.” https://thebulletin.org/doomsday-clock/timeline

Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 2023c. “The Doomsday Clock.” https://thebulletin.org/doomsday-clock/#nav_menu

Christian, B. 2017. “Stephen Hawking Believes We Have 100 Years Left on Earth – and He’s Not the Only One.” Wired, May 19. https://www.wired.co.uk/article/stephen-hawking-100-years-on-earth-prediction-starmus-festival

Crowder, L. 2018. “Steven Pinker: Real Risks, Undeniable Progress.” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, April 11. https://thebulletin.org/2018/04/steven-pinker-real-risks- undeniable-progress

Felitti, V. J., R. F. Anda, D. Nordenberg, D. F. Williamson, A. M. Spitz, V. Edwards, M. P. Koss, and J. S. Marks. 1998. “Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study.”

American Journal of Preventive Medicine 14 (4): 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

IBM Corporation. 2021. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

Mir, R. H., G. Sawhney, F. H. Pottoo, R. Mohi-Ud-Din, S. Madishetti, S. M. Jachak, Z. Ahmed, and M. H. Masoodi. 2020. “Role of Environmental Pollutants in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Review.” Environmental Science and Pollution Research 27 (36): 44724–44742. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11356-020-09964-x

Pinker, S. 2018. Enlightenment Now: The Case for Reason, Science, Humanism, and Progress. New York, NY: Penguin Random House.

Sherif, M. 1956. “Experiments in Group Conflict.” Scientific American 195 (5): 54–59.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2020. “Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health.” (HHS Publication No. PEP20-07- 01-001, NSDUH Series H-55). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://library.samhsa.gov/product/results-2019-national-survey-drug-use-and-health-nsduh-key-substance-use-and-mental-health

University of Washington Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation – Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network. 2023. Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD 2019) Results. http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool

US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2023a. “Age-Adjusted Death Rates for Selected Causes of Death, by Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin: United States, Selected Years 1950–2019.” https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/2020-2021/SlctMort.pdf

US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2023b. “Suicide Data and Statistics.” https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/facts/data.html

World Health Organization. 2022. “COVID-19 Pandemic Triggers 25% Increase in Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression Worldwide.” https://www.who.int/news/item/02-03-2022-covid-19-pandemic-triggers-25-increase-in-prevalence-of-anxiety-and-depression-worldwide

World Health Organization. 2023a. “Social Determinants of Health.” https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1

World Health Organization. 2023b. “WHO COVID-19 Dashboard.” https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases?n=c

I appreciate and greatly value your contributions and always look forward to your newsletter! I like the approach of continuing to broaden the focus of the clock to better reflect the multifactorial interrelationships between individuals and society.

Jay Joerger, Ed.D.

Psychologist

I am 65, and I have never felt such despair and sadness as I have since Trump was elected this year. The entire world, not just America, is leaning into cruel fascism and willing ignorance, little is being done to oppose it, and I see the problem is the nature of Man itself.

My mental health is complete shit. It would be irrational to think that this global nightmare would not harm minds and bodies.