Introduction: (Almost) everything you wanted to know about tipping points, but were too afraid to ask

By Jessica McKenzie | March 12, 2025

Introduction: (Almost) everything you wanted to know about tipping points, but were too afraid to ask

By Jessica McKenzie | March 12, 2025

One of the most pressing questions facing climate scientists, and the world at large, is whether human-caused global warming could trigger changes in the climate system that will radically reshape the Earth as we know it. The evidence is mounting that these vast changes are not only possible, but increasingly likely as the Earth warms. But how close the world is to crossing these so-called “tipping points” is a matter of vigorous scientific debate.

The phrase “tipping point” was first coined by sociologist Morton Grodzins to describe segregation and white flight in the 1950s. It was later popularized in the early aughts by Malcolm Gladwell, who published a blockbuster popular science book called The Tipping Point, which looked at sudden social shifts through an epidemiological lens—how ideas spread like viruses. It wasn’t until 2008 that the metaphor formally entered climate science, when Tim Lenton and his colleagues published the paper “Tipping elements in the Earth’s climate system” in The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The idea that there could be sudden and irreversible changes within the Earth’s climate system was not new. In the mid-20th century, scientists studying ice and sediment cores found evidence of abrupt warming and cooling periods in the Earth’s geologic history and inferred that abrupt climatic shifts could happen again. In past reports by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, these were called “climate surprises,” or the more cumbersome “large-scale discontinuities in the climate system.” But the tipping point metaphor caught on in a way these other phrases didn’t.

Even now, the exact definition of a tipping point varies somewhat, although there are broad commonalities.

Thomas Stocker, a climate scientist at the Oeschger Centre for Climate Change Research, defines it as “…dynamical systems that have more than one stable equilibrium, and where these transitions occur from one equilibrium to the next, when you change an external parameter or a forcing, that point is called a tipping point.”

David Armstrong McKay, a researcher at the Stockholm Resilience Centre, says a tipping point is “when change in a system becomes self-sustaining; once the system has been pushed beyond a particular threshold, and then that triggers kind of a state shift, so that system will completely change state in a way which is often abrupt or irreversible, but not necessarily in every case. The main thing is the self-sustaining change aspect, so that once it’s been triggered, it will just keep on going until you eventually reach that new state.”

Lenton, one of the researchers who first used the phrase in the context of climate science, defines a tipping point as “a situation within some system where amplifying feedback within that system gets so strong that it can overwhelm whatever damping feedback you have in the system, and it can get strong enough to create a self-sustaining or self-propelling change within the system.”

The Earth system is enormously complex, and so scientists have attempted to break it down into smaller pieces that could be vulnerable to abrupt or irreversible changes—what Lenton and his colleagues called “tipping elements.” Some of these would have impacts that reverberate around the world once they were irreversibly crossed. If, for example, the West Antarctic Ice Sheet broke up, it could raise global sea levels by three meters. In the United States alone, that would result in the loss of 28,800 square miles of land and displace millions of people (Strauss 2014). The impacts of “regional” tipping elements, like the mass die-off of coral reefs, would be more limited in geographic scope, but could still have widespread and catastrophic impacts.

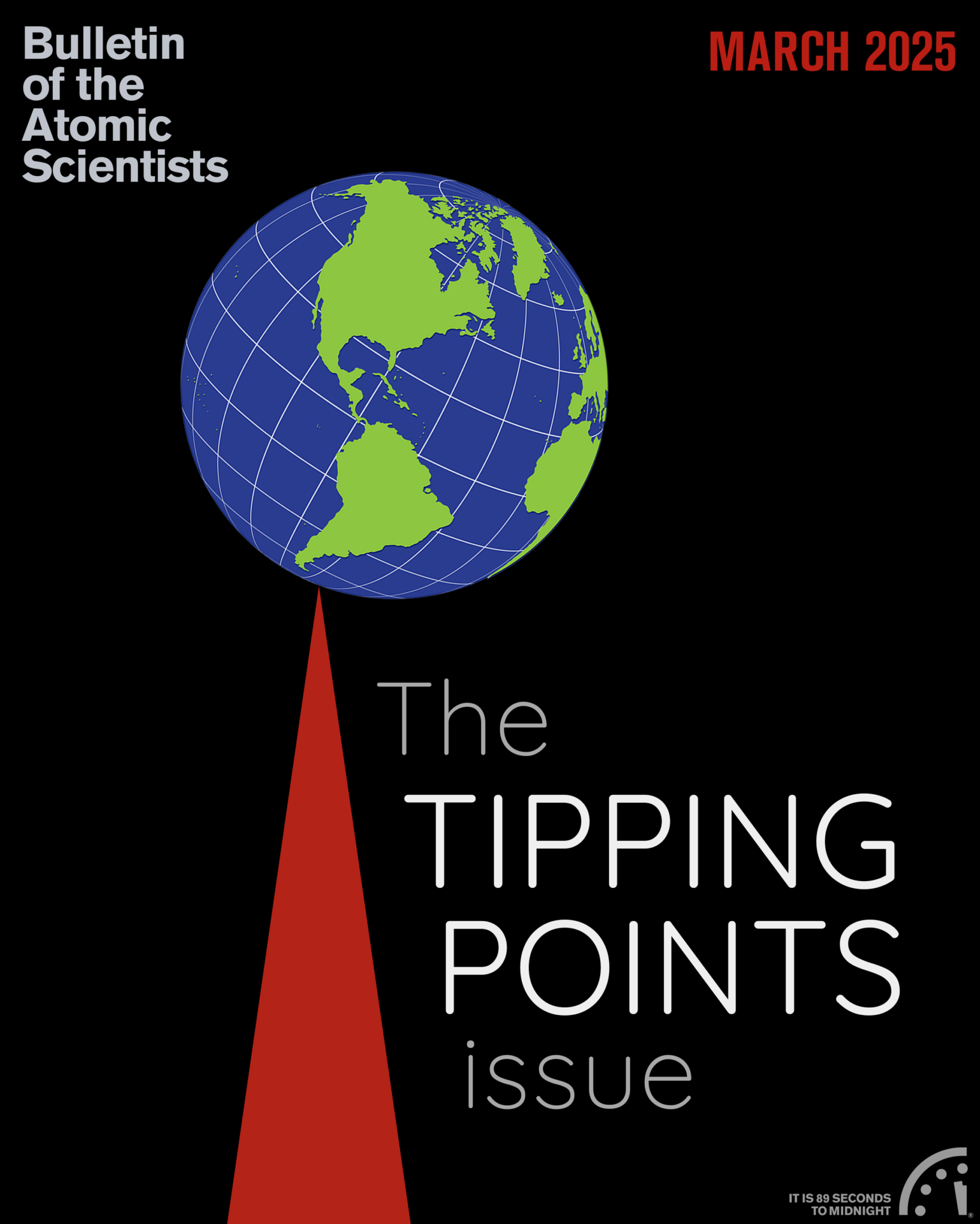

This issue of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists considers several of these tipping elements in depth: Twila Moon, a scientist with the National Snow and Ice Data Center at the University of Colorado Boulder, considers the possibility that the Greenland Ice Sheet has already passed an irreversible tipping point, and what can be done to slow that process. Henk Dijkstra of Utrecht University dissects the hotly contested risk that the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation could slow or cease entirely. Vladimir Romanovsky, a scientist at the University of Alaska’s Permafrost Laboratory, details his latest findings on the possibility of sudden, abrupt thawing of Boreal permafrost in the Arctic. And the Brazilian scientist and meteorologist Carlos Nobre explains how climate change and deliberate destruction have brought the Amazon rainforest to the brink of crisis.

Several authors take a step back from individual tipping elements to consider the bigger picture: In “Is scientific reticence hindering climate understanding?” climate policy expert David Spratt considers the continued reluctance of some scientific organizations (like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) to give serious and sustained attention to worst-case scenarios that could result from crossing planetary tipping points.

Femke Nijsse, a complexity scientist at the University of Exeter, looks at the possibility that there are “positive tipping points” within the social, technological, and cultural realms that could accelerate climate action. (This has also been a recent area of interest for Tim Lenton, who has a book coming out on positive tipping points later this year.) In this way, McKay points out, tipping points have come “full circle,” and are now back in the social sciences where they first originated.

Anthropologist and historian Joseph Tainter explains his theory of societal collapse, and we discuss the possible relevance of the tipping point metaphor to his work—most of which predated the widespread adoption of the term.

And finally, in “Climate change will surprise us, but so-called ‘tipping points’ may lead us astray,” Robert Kopp, Elisabeth Gilmore, and Rachael Shwom look at how the tipping point metaphor within climate science and particularly within climate science communication could ultimately obscure and confuse the public’s perception of climate risks.

Moving away from the tipping point question, there is also an article by Samuel Justin Sinclair and David Silbersweig on the correlation between mental health, mortality, and the Bulletin’s own Doomsday Clock.

There is concern, even among climate scientists who loudly and proudly use the tipping point metaphor in their work, that it will be misconstrued by the public to mean that there is a single temperature threshold after which all hope is lost. Although these scientists consider a runaway global warming scenario possible in theory, they think it is a very, very long way off. Brian Kahn, a research scientist at NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, says atmospheric carbon dioxide levels would have to be above a couple thousand parts per million (Schmidt 2018). (As of early February 2025, atmospheric carbon dioxide levels were just over 425 parts per million.) And although in many cases, crossing one planetary threshold increases the likelihood of crossing another, they won’t all immediately fall like dominoes.

“It’s never too late, even if we do pass one of these tipping points or several of the tipping points we suggest are out there, that doesn’t mean that we give up, because we can still prevent further tipping points,” says McKay.

“We’ve all got some agency to be part of triggering positive tipping points that can accelerate us out of … the existential trouble that’s otherwise going to be caused by the bad tipping points in the climate and the Earth system,” says Lenton.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Earth system, Gulf Stream, climate change, global warming, tipping point

Topics: Climate Change, Special Topics

Earth natural systems are not one monolith. There are perhaps several hundred major systems that lend themselves to ‘tipping.’ Most are driven, however, by other tipping systems, connected in ways science knows about, and still others that science is still discovering and analyzing. Without immersing oneself into the real ecology of the planet, it is difficult to not only observe, but intuit the complexity that defines expected fairly steady states of balanced but dynamic energies. However, as human-caused entropy interjects itself into pre-human ecology, which would include meteorology and climatology and oceanography, the dynamics of entropic balance become much more… Read more »

The idea that there are positive as well as negative “tipping points” is consonant with the International Organization for Standardization’s definition of risk in ISO31000 as “the effect of uncertainty on objectives”. This definition allows for positive as well as negative risks.

Alas, positive tipping points, like other positive risks, generally require human effort, whereas their negative counterparts become more likely in its absence.