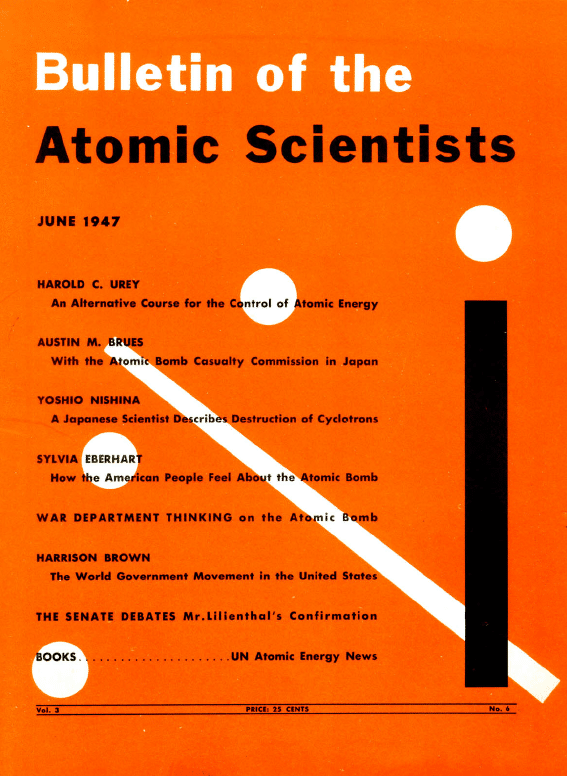

1947: How the American people feel about the atomic bomb

By Sylvia Eberhart | December 7, 2020

1947: How the American people feel about the atomic bomb

By Sylvia Eberhart | December 7, 2020

Editor’s note: Early in 1946 the Committee on the Social Aspects of Atomic Energy, of the Social Science Research Council, proposed a study of “the thinking of the American public on matters relating to the development of the atomic bomb and its effect on attitudes on international relations.” A sub-committee was formed for the planning of such a study, and funds were provided through Cornell University by the Carnegie Corporation and the Rockefeller Foundation. This report was prepared by Mrs. Eberhart at the request of Dr. Leonard S. Cottrell, Jr., chairman of the sub-committee. It was originally published in the June 1947 issue of the Bulletin. It is republished here as part of our special issue commemorating the 75th year of the magazine.

Not the least of the questions confronting the scientists and public leaders who must cope with the problem of the atomic bomb is, What is the public frame of mind? For better or for worse, the bomb is a political problem, and “public opinion,” however measured or guessed at, is a political instrument. Whatever social or political action is taken as a result of the discovery of the bomb will inevitably involve the people generally. What are their attitudes toward the bomb and toward the issues it has raised?

This study was planned so that both polling and intensive methods of surveying public opinion were employed.[1] The impending Naval experiments with the bomb at Bikini seemed to the sub-committee to offer a focal opportunity for appraising public reactions; the surveys were accordingly conducted in two parts, one part in June and the other in August. This article deals almost entirely with the findings of the intensive surveys.

To some it will perhaps be incredible that as many as two percent of the American people should not by last August have heard of the atomic bomb. To the investigator of public opinion the fact that such an event as the release of atomic bombs over Japan came within the ken of 98 percent of the heterogeneous American public is most impressive. In the full report[2] of the survey, public cognizance of the bomb is described thus:

The impact of the atomic bomb on the minds of the American people has had few parallels in our history. All but the most inaccessible few know about the bomb. People who have never heard of the United Nations and have neither interest in nor knowledge of world affairs know that a new and tremendous force has been discovered.

Few people in present-day America venture to depreciate the power of the bomb. While public concepts of the bomb vary from the very simple to the highly sophisticated, they almost universally emphasize its destructiveness. Many people were surprised that the bombs did not destroy more ships at Bikini, but the Bikini tests did not alter the pervading belief that the atomic bomb stands in a class of its own, a weapon of awe-inspiring power.

But has the existence of the bomb aroused fear? Are the people worried by predictions that another war may bring unprecedented devastation into their own country? Are they following with anxious interest the efforts of their leaders to create safeguards against atomic war?

On the whole, it must be concluded from the survey that the threat of the bomb does not greatly preoccupy the people, and that they are not giving special attention to the issues in which it is involved.

Public awareness of the issues of control

That a very large part of the American public is not concerned about the issues involving the bomb is strongly indicated by the level of their information about the most prominent of these issues. At the time of the survey, more than a year after the United Nations had come into existence and in spite of the virtually unlimited attention devoted to it up to that time by press and radio, one-third of the people were unable to say what the United Nations was designed to accomplish, in even such general terms as “to work for peace” or “to get the countries of the world to cooperate.” These people were scarcely aware, if not totally unaware, of the existence of the organization to which it had been proposed that the control of the bomb should be entrusted.

It is of course possible to separate the opinions and attitudes of obviously uninformed people from those of people who are at least relatively well informed. But to the question, “Cannot the views of the uninformed on public issues, if they have any, be disregarded?” it must be answered that ignorance does not carry with it an automatic disenfranchisement. One-fifth of the people who reported that they had voted in the 1944 national elections were included among those who did not know what the United Nations is.

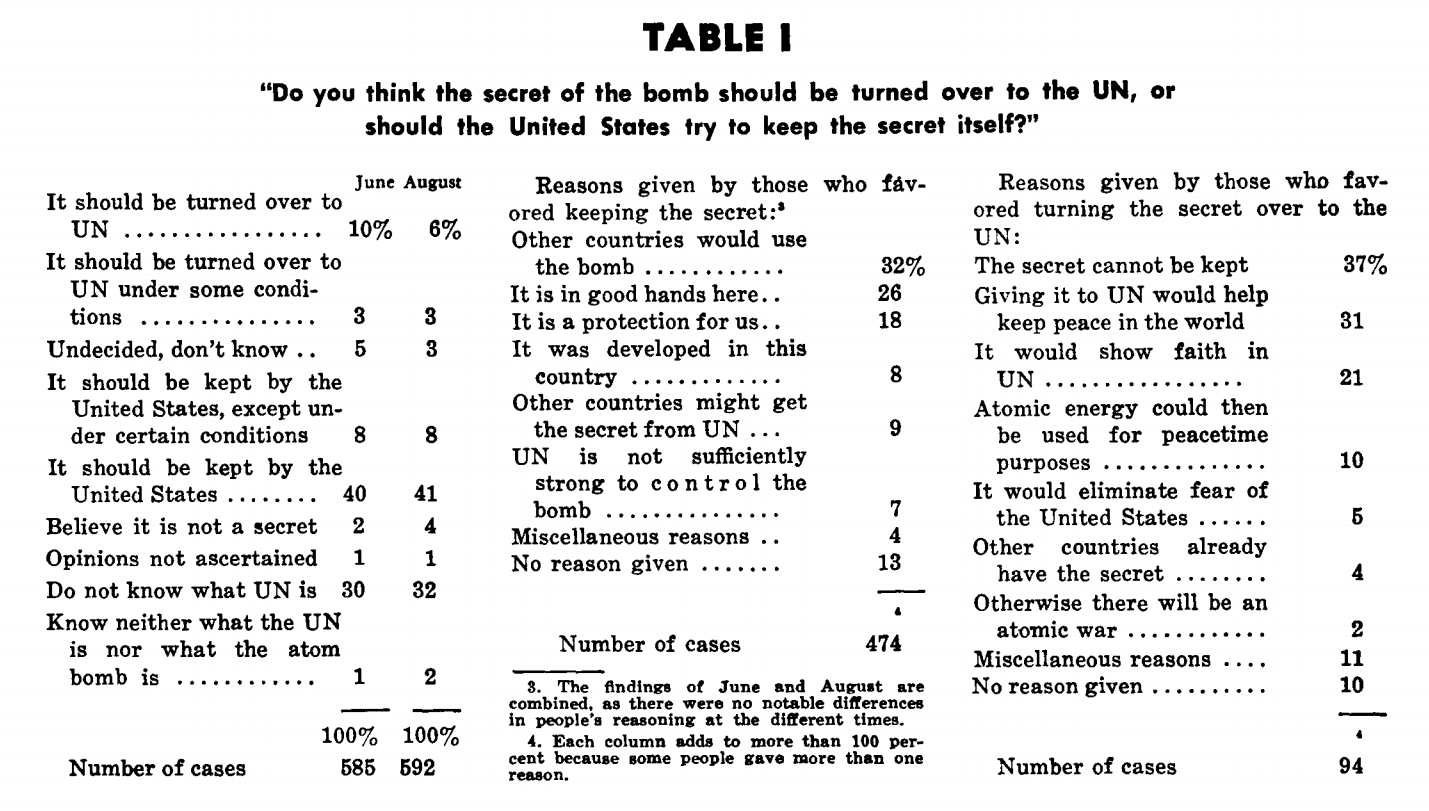

Moreover, many of the people who did have some cognizance of the UN and so were asked to express an opinion about the desirability of giving it control over the bomb did not recognize the meaning of the issue. They were overwhelmingly opposed to the proposal (Table 1), but it was quite clear in their reasoning that most of them understood it to mean giving the bomb secret away to foreign countries. Publicity since then on the debate over the issue may have increased public understanding. But it is plain that as late as last summer public understanding had a long way to go.

It is evident that many people’s—probably most people’s—thinking about the bomb must stop far short of the issues involving the bomb that actually confront the nation. But virtually the entire adult population of the country can think about the bomb itself, even if not in a way that is oriented toward solving the problems its development has raised. Is their failure to follow the news about control of the bomb a function of the beliefs they hold regarding the bomb itself? Is it due to a sense of security arising from our monopoly of the bomb? Or is it the result of more general attitudes, related not simply to the bomb but to any problem not intimately a part of their personal day-to-day preoccupations? The answer is that it is due in some degree to all these factors, but probably most of all to the last.

Understanding of the Bomb itself

The conception the people have of the bomb is by no means unambiguous, even though they are greatly impressed by the bomb’s destructive power.

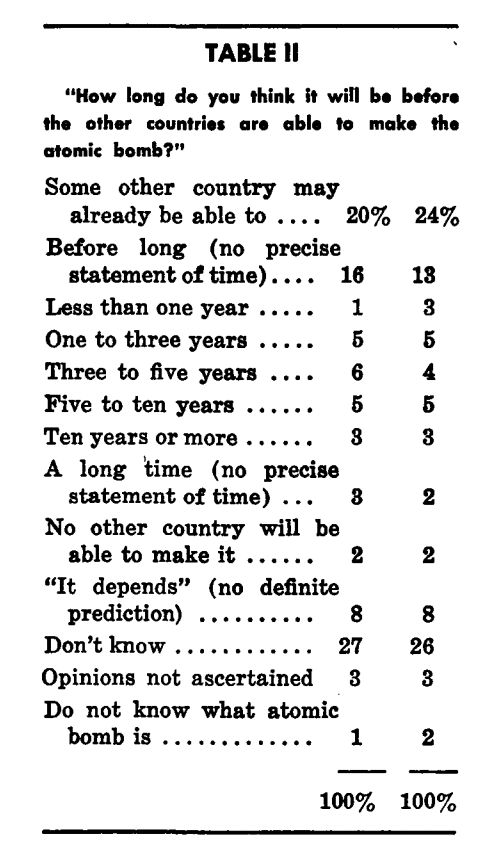

When confronted with the direct question “How long do you think it will be before the other countries are able to make the atomic bomb?” (Table 2), at least a quarter of the people felt unable to give any answer. Those who did answer, however, were for the most part agreed that the time would not be very long. Only two in a hundred said that other countries could never make the bomb, and only five in a hundred that it would take them as long as ten years or simply “a long time.” Many said it was quite possible that some other country might already be making the bombs; very few felt sure that this was the case, but they spoke of it as a possibility.

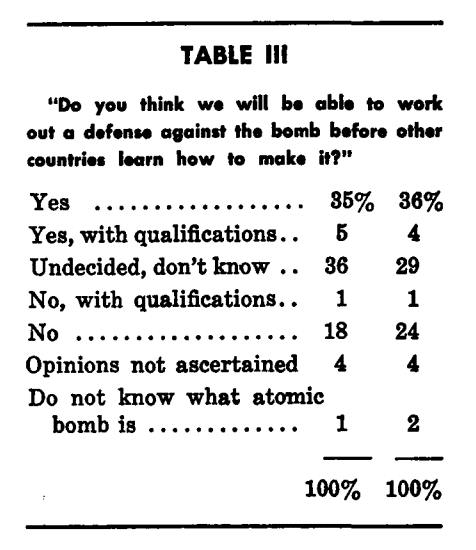

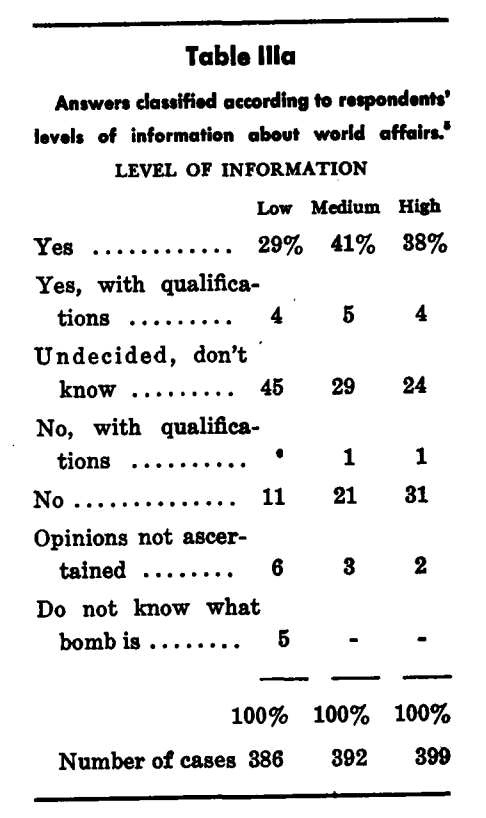

The conjectures of experts on the length of time it will take other countries to develop the bomb appear, therefore, to have had a wide hearing. On the question of a defense against the bomb (Table 3), the pessimistic opinions of authorities are not nearly as widely accepted. A third of the people would venture no opinions when asked whether they thought we could develop a defense, a quarter expressed the opinion that “there is no defense against the bomb,” but well over a third believed that we would work out a defense before other countries could make the bomb.

No examination of newspaper treatment of the defense question at the time of the survey has been attempted, but it seems likely that the two questions received quite different kinds of treatment in the press and on the radio, for it is significant that even among people who gave evidence of being relatively well informed on world affairs the opinion that we would succeed in developing a defense was very widespread (Table 3a). The reasoning with which people supported this opinion points to an attitude that probably accounts for a good deal of public complacency. The people have immense faith in American science, American ingenuity, and American resources. They argue that since the scientists were able to invent the bomb, they can invent a defense, and that the United States “always keeps ahead.”

No doubt the deficiencies in people’s understanding of the bomb make it easier for them to put the bomb problem out of their minds. But mere reiteration that the development of the bomb is accessible to other countries and that there is no known defense against it will not necessarily jar the public into appreciably greater concern. People can accept such judgments without incorporating them into their attitudes and ways of thinking. For example, a large group of people argued in the survey that the development of the bomb had made peace easier to keep, rather than harder, because other countries were afraid of it and would not dare to provoke a war with us. Many of these same people, in answer to the direct question, declared freely that other countries would probably develop the bomb within a relatively short time. The information they had apparently absorbed had not shifted our monopoly of the bomb from the central position it occupied in their thinking.

This phenomenon—a not uncommon one—of public opinion is even more conspicuous in people’s attitude toward our keeping the secret of the bomb rather than relinquishing it to UN control. Most of the people who opposed turning the secret over to the UN had expressed the opinion, just before, that other countries could develop the bomb fairly soon; yet many of them made no acknowledgment of the bearing of that probability on the question of UN control of the bomb.

Moreover, descriptions of the extraordinary power of the bomb, including its inescapability, may offer a kind of psychological refuge. Many people reasoned that the bomb was a contribution to peace because it seemed unthinkable that governments would dare to provoke a war when so terrible a weapon might be used by any side. If the menace is universally inescapable, if retaliation is inevitable, then may we not all be safe? Such reasoning may be more an expression of hope than of conviction, but apparently it plays its part in enabling people to turn their backs on the bomb problem.

“I let the government worry”

To the question, “How worried do you think people in this country are about the atomic bomb? How about yourself?” half the people said they were not at all worried, many others that they were worried very little. Only a quarter admitted to being worried. The most striking aspect of the explanations people gave for not being worried was how little they were based on the argument that there is no threat to us in the bomb. Only one “non-worrier” in seven explained his frame of mind in that way—by the statement, for example, that we alone have the bomb, or that the bomb will never be used, that its dangerousness has been exaggerated (a remark made by only about one percent in the survey), that we will have a defense, or that no other country could make the bomb. Another smaller group said they felt personally safe, either because their advanced age made it unlikely that they would live to see another war, or because they lived in places that would never be subjected to attack.

Most of the “non-worriers” acknowledge in their explanations, openly or by implication, that the bomb constitutes a danger, and as a group their answers to the questions about other countries’ development of the bomb and our having a defense against it were only a little more optimistic than those of the people who said they were worried. Their reasons for not worrying were for the most part reasons that they might apply to any issue that does not immediately affect them—that “there is no use worrying about something you can’t help,” that they are too busy with their own affairs to think about anything so remote as the atomic bomb, that the bomb represents a problem for the government or the scientists to worry about, not the ordinary citizen. These quotations from interviews are illustrative of the variety of ways in which this attitude is expressed:

I’m not worried. I think that the head officials or whatever it is would know how to use it.

I feel like our government will take care of its own, and there is no need for me to worry about something I have no control over.

I know the bomb can wipe out cities, but I let the government worry about it.

I let the people who are qualified in those things do the worrying. I am just one of the many people who accept circumstances as they are. To me, it is just like if you were living in a country where there were earthquakes. What good would it do you to go to bed every night worrying whether there would be an earthquake?

In a personal sense I’m not worried. Of course I do have the hope that it’ll never be used . . . I have the feeling that worried or not it wouldn’t make any difference.

I don’t think I devote much time to worrying about it. The building business is too complicated now for me to worry about the bomb. It’s too remote.

I got everything I need. From the morning, when I get up, I pick apples and I get a dollar a bushel. So why should I worry about the bomb? I don’t need to worry. Let it come. I don’t think about it.

Here too there were evidences that people may take refuge from worry in the very power of the bomb itself; some professed to find comfort in the belief that “you wouldn’t even know it if one hit.” Others remarked that “you cannot be killed any deader by an atomic bomb than you can by a bullet or a block-buster.”

Such views as these are undoubtedly subject to hasty revision in the face of imminent danger. There can be no doubt of the people’s recognition of the terrible power of the bomb, and a threatening incident involving the bomb would certainly cause a strong public reaction. But for most of the people the danger is not on the horizon. Accordingly, the bomb problem suffers the same kind of popular neglect that many another less critical social issue receives.

Attitudes toward the United States’ role in world affairs

It must be recognized that for a sizable proportion of the American public international affairs have very little reality. The psychological imminence of world events varies enormously within the population. Despite the tremendous network of newspapers, radio, magazines, and other educational media, only a minority of the people can be considered actively conversant with contemporary world problems.

For the most part, public opinion regarding the role of the United States in world affairs deals in the broadest generalities. Current public opinion embraces the generalizations that the United States cannot remain aloof from the rest of the world, and that international cooperation is essential for the promotion of peace. The people in the survey overwhelmingly rejected the proposition that “we should keep to ourselves and not have anything to do with the rest of the world.” Similarly, they rejected the proposition that “we should use our army and navy to make other countries do what we think they should.” Those who had some familiarity with the UN expressed approval of the existence of such an organization, supported the principle that the United States should have no greater voice in it than any of the other large nations, and agreed that it should have the power to settle disputes between the United States and other countries. Many people even accepted the proposal that we should participate in a more extended form of world organization, when it was defined as one in which “we would have to follow the decisions of the majority of nations.”

But on specific issues the broad principles they espouse do not serve them as a guide. On specific issues they still tend to think of immediate American interests, in the narrow framework in which they are able to see them. For example, a majority were opposed to the British loan (a current topic at the time of the survey) on the grounds that the British were already too much indebted to us, and that we could not afford to lend them so much money. They were overwhelmingly opposed to our turning the bomb over to the UN, on the grounds that we would thus foolishly jeopardize our own security. It must be emphasized that they did not see in our monopoly of the bomb any suggestion of a hostile policy. They reasoned that so long as we alone have it, not only we but the rest of the world will be safe from atomic warfare, inasmuch as we have no ambitions that would make us the aggressors in a war. That the matter may not appear in this light to the other fellow entered into the thinking of very few, however. In principle they would undoubtedly acknowledge the truism that international cooperation involves willingness to compromise on everyone’s part, but the main criticisms they had to offer of our government’s conduct in its relations with other countries was that it was “giving in” too much.

Russia is very much in the minds of the people who give any thought to world affairs, and distrust and suspicion of her are very widespread. Most of the people believe that we cannot depend on her to be friendly to us, and their desire to keep the bomb secret, their criticisms of our giving in too much, their dissatisfactions with the progress of the UN are often related to misgivings about Russia. The proportion of people who expressed consistently favorable attitudes toward Russia in the survey was negligible, and evidences of even a tolerant attitude were sparse.

Public acceptance of the idea of international cooperation or international organization must be appraised in the light of all these limitations. How well the people’s tendency to look to cooperation with other countries as a promising approach to world peace will withstand the strain of the inevitable international discords is problematic.

A note about popular sources of information

The survey included a brief investigation of the sources of the people’s information about the bomb, as reported by themselves. Eighty-five percent of the people had radios (in working order), and an almost equal proportion read daily newspapers. More than half said they read magazines—mostly the monthly digest magazines and the weeklies containing fiction and miscellaneous articles. About a tenth read news magazines, and about twice as many the news-picture magazines. Magazines devoted to more extended discussion of public affairs were read by only a small percentage. All these figures, derived from the respondents’ statements, check closely with other sources of such data for the population as a whole.

About 1 person in 14 had available none of the popular media of information—had no radio, read no paper or magazine. Many, of course, had all three sources at hand.

Less than 4 people in 10 said they listen to radio programs dealing with world affairs. Even among people with college education, only 6 in 10 reported listening to any such programs. Among the most poorly educated, the incidence of listening was very low.

Generally speaking, people reported having learned something about the bomb from whichever of the media they reported having. A very large majority had read something about it in the papers and heard about it on the radio. Almost half had read about it in magazines. Only a third, however, remembered seeing any movies or newsreels of the bomb; among these people, movies ranked quite high as the medium that had given them “the best idea of how destructive the atomic bomb is,” but very low as the medium from which they had obtained most of their information. Less than one percent said they had obtained most of their information about the bomb from books.

It is of interest that the people who had had information about the bomb from both radio and newspapers tended to name radio as the more trustworthy source. Those to whom magazines were also available named magazines most frequently as the most trustworthy. The tendency to favor radio over newspapers was particularly pronounced among the less educated people; among the better educated, preferences were more equally divided between the two media.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: 2024 election, United Nations, archive75, atomic bomb, nuclear weapons, public opinion

Topics: Nuclear Weapons