What if potatoes grew on trees? An interview with the Breadfruit Institute’s Diane Ragone

By Dan Drollette Jr | May 7, 2024

What if potatoes grew on trees? An interview with the Breadfruit Institute’s Diane Ragone

By Dan Drollette Jr | May 7, 2024

In 2007, I went to the island of Kaua’i for two weeks for an environmental science journalism immersion seminar led by the National Tropical Botanical Garden, an organization that seeks to save tropical plants from extinction through science, conservation, and research. It was a great chance to see what is known as the “Garden Island” of the Hawai’ian archipelago, and to immerse one’s self in some of its culture; the organizers made it a point to teach us about the pre-contact ways of catching fish, raising food, making tapa cloth from bark, and the meanings of the traditional music and dances.

The staff also introduced us to a relatively new initiative, known as the Breadfruit Institute. The gist was that these scientists wanted to bring back an overlooked, indigenous food source, and had embarked on a years-long project to interview Pacific Islanders about traditional cultural practices regarding this food’s planting, cultivating, harvesting, and storing, and to document their knowledge in photographs, recordings, and videotapes before it all disappeared under a tsunami of fast-food joints. (Even on remote islands, it seems that many people now eat more Spam than locally caught fish and vegetables.)

What a visitor could see on the ground was rather modest: some mature trees; many recordings and tapes; and many, many rows of small seedlings in greenhouses.

But its ambitions were big: an attempt to bring back from obscurity a more-or-less forgotten, low-cost, sustainable, locally grown foodstuff, suitable to the Global South, that is not reliant on lots of petro-chemicals, insecticides, and herbicides. And good for fighting climate change, to boot.

Their effort has since picked up steam, judging from their international conferences, papers, and propagation efforts. The organization has helped to plant 10,000 breadfruit trees throughout the islands since 2012 and has significantly raised public awareness of this foodstuff—through breadfruit festivals, cookoffs, guidebooks, cookbooks, planting FAQs, and coloring books, some of which are in both English and Hawai’ian.

In the following interview, the Breadfruit Institute’s founder, Diane Ragone, describes how things have changed since those early years, how she got interested in the problem, the organization’s goals, the science behind the plant’s propagation, and the tale of this fruit’s rise, fall, and re-birth.

Ragone also touches on some of this fruit’s colorful history: The mutiny against the notorious Captain Bligh occurred while he and his crew were transporting a load of breadfruit from Tahiti. (The goal of his employers was to find a nutritious, fast-growing fruit that could be used as a cheap food source for slave laborers on the vast sugar plantations of the West Indies.) Legend has it that when water on board his ship ran low, Bligh prioritized keeping his precious breadfruit plants alive over giving his crew drinking water—hence the mutiny.

(Editor’s note: This interview has been condensed and edited for brevity and clarity)

Dan Drollette Jr: What is your 30-second “elevator speech” as to what the Breadfruit Institute is, and what its goals are?

Diane Ragone: That’s hard, but I’ll try to be concise.

The Breadfruit Institute is a program at the National Tropical Botanical Garden here in Hawai’i, and its mission is to promote the conservation, study, and use of breadfruit for food and reforestation. We manage the world’s largest collection of breadfruit varieties, with 150 varieties conserved in living collections at two of our gardens: one in Hāna on the island of Maui, and one on the island of Kaua’i—the facility you visited—both in the Hawai’ian archipelago.

Some of these varieties are extremely rare, if not endangered; others are already entirely gone from their home islands.

This collection not only allows us to conserve the genetic diversity of breadfruit but to study all these varieties, with the goal of better understanding the species—and that allows us to select good-quality varieties for distribution in tree-planting projects.

Drollette: It sounds somewhat like an organization in Peru, called the Potato Center[1]: Here’s a traditional crop found in the New World, with only a handful of varieties in wide use out of the hundreds available, with scientists trying to preserve its diversity while encouraging people to use it for more than just junk food. Though I guess the comparison breaks down a bit, because breadfruit isn’t really known to much of the world. And if I understand correctly, breadfruit is a pretty healthful thing to eat.

Ragone: The resemblance to the International Potato Center is more than coincidence; they were a real role model for us. If we have time, I hope to get back to that later.

But, yes, breadfruit is like a starchy annual field crop—in other words, much like the potato, sweet potato, or other crops that feed most of humanity.

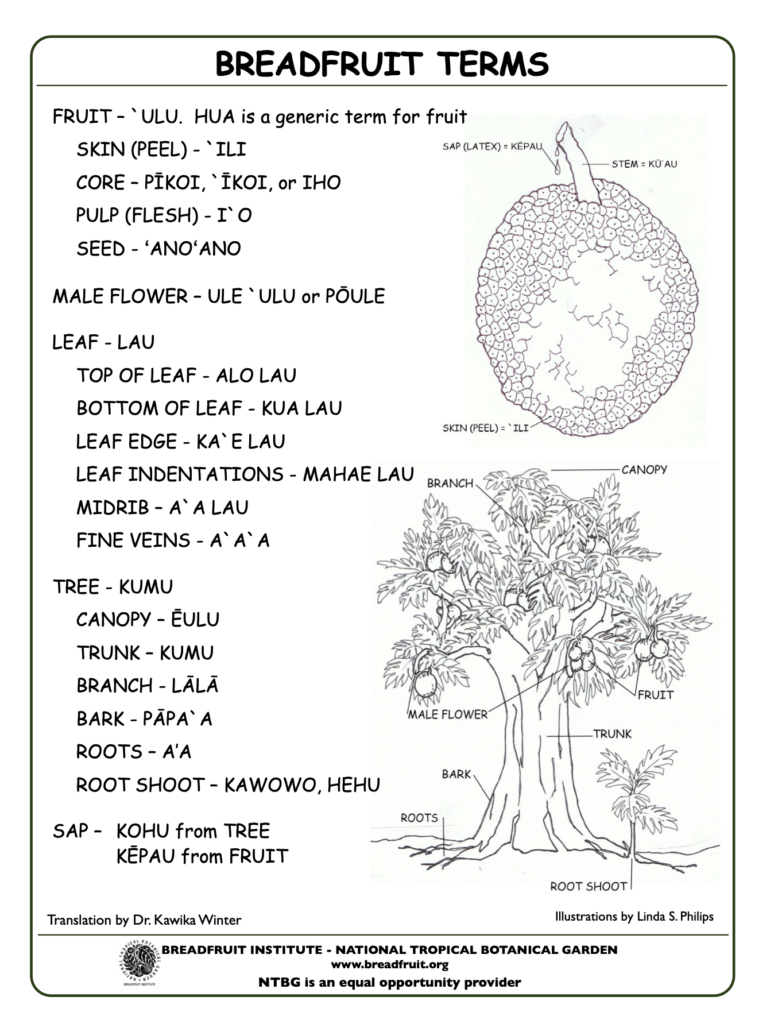

But breadfruit is unique in that unlike a potato, it grows on a tree—a perennial, tropical tree—and it produces a fruit which contains highly complex carbohydrates. It gives you energy and has some protein, as well as a lot of good nutrients, minerals, vitamins, and fiber that are essential for human health, as well as helps to achieve more balanced blood sugar levels.

But the beauty of breadfruit is that it grows on a long-lived tree—several decades—so after it’s been planted you can keep harvesting from the same trees over and over. Because it’s a perennial, it also requires less inputs, such as water and fertilizer, than annual crops that must be re-planted every year.

And it’s very versatile. For example, if I ask you to name a fruit, what pops into your mind?

Drollette: Apples? Oranges?

Ragone: So breadfruit is a true fruit like those are, but more versatile in that when it’s small and green and immature, it’s more reminiscent of an artichoke heart in flavor and texture. It has to be cooked at that stage, but that’s what it’s like then.

And when it ripens to the firm, starchy, mature stage—which is when it’s traditionally and typically harvested and used—then it’s more like a potato.

As it continues on its journey of maturing, it ripens into something sweet and soft—almost like a pudding. At that point, it’s a whole different food in terms of how it can be tasted, eaten, and used.

So it’s very versatile—both in its uses and in terms of nutrition.

Drollette: If it has so many things going for it, then why did the use of breadfruit decline?

Ragone: It’s a combination of factors.

Breadfruit originated and was domesticated in the Pacific Islands, probably towards the Malay Peninsula. And for several thousand years, it has been an important staple crop throughout the islands. Hawai’i is kind of at the end of breadfruit’s travels because of the way that the ancient Polynesians came to settle and immigrate throughout the Pacific—they essentially got to Hawai’i toward the tail end of their travels. But when they did arrive, they brought breadfruit with them.

And the subsequent use—or fall into disuse—of breadfruit was a very important part of all the changes that would come about with the colonization of the Pacific Islands, particularly in the islands of Micronesia[2], which were later colonized by the Spaniards, then the Germans, then the Japanese, and then the Americans.

There were just absolutely profound changes associated with each of these contacts with Asians or Europeans—new diseases were brought in each time, along with other health problems caused by each collision of cultures.

Indigenous people managed to maintain their traditional lifestyles for a long time, but there was a real profound shift with the arrival of World War II, which pretty much transformed everything everywhere on the planet. The war opened up areas of the islands in the Pacific that had really had pretty minimal encounters with the outside world previously.

I think there was a real shift then, including a profound change in diet,[3] so people weren’t planting—or re-planting—as many breadfruit trees. And since then, there’s been a change in the environment with more impacts from events such as serious droughts, hurricanes, and typhoons. And of course those environmental impacts have accelerated tremendously in the past few decades due to climate change.

In the past 20 or 30 years, we’ve been seeing a similar thing happen in the Caribbean, where breadfruit was introduced over two centuries ago from Tahiti. Back in the early 1800s, there were about a million breadfruit trees in the Caribbean, according to a study done in the 1970s. Now there are fewer than 100,000 or so in that region, mainly because of hurricanes but also because of the cultural and economic changes of the past few decades.

Drollette: I’m getting the impression that the breadfruit work seems to have really taken off since I saw it at the National Tropical Botanical Garden around 2007. It was much more lab-based then, and on a different scale. My memory is of rows of little plant shoots in greenhouses.

Ragone: Well, yes to all of those things. We later had a workshop, and then a really big seminar in 2017 followed by breadfruit cookoffs, breadfruit cookbooks, breadfruit coloring books, and now there’s at least a few commercial gardens selling breadfruit trees[4].

When you visited, we were still in the throes of ramping up from long-term research projects—like, 10-year projects to gather specimens from islands all over the Pacific and learn more about what we collected, with the goal of raising really good-quality varieties to introduce to people and then distribute globally. It took quite a few years, and we’re still trying to figure some of this out.

But how to propagate breadfruit, how to provide good-quality planting material—that was the focus then in the early stages, and a key item. Because traditionally, most varieties of breadfruit are seedless, which means you have to propagate it vegetatively from a root sucker that grows up into a tree. That’s how the Pacific Islanders spread it throughout the Pacific; that’s how Captain Bligh got it into the Caribbean[5].

But it’s not a feasible, long-term way to really plant breadfruit trees in quantity.

And that’s one reason that breadfruit use and the number of trees declined over the decades; there just wasn’t a lot of good-quality planting material after the trees were damaged.

We realized after some test projects that using traditional methods wasn’t going to work; we needed to figure out a different way of doing it. So we looked at tissue culture, which is a form of in vitro propagation, which is very common in the ornamental plant industry—I think every African Violet and every poinsettia in North America is grown in tissue culture[6].

We got the idea after running across one paper published in 2001, out of the Caribbean, about tissue-culturing breadfruit. We started a project in 2003, and by 2007 we successfully got some of the very first breadfruit plants—little tissue-cultured plants—which is probably what you would have seen.

And that was a real game-changer.

Because then one of our partners—the lab of Dr. Susan Murch at the University of British Columbia in Okanagan, Canada—was able to do so many fundamental research projects, such as nutritional analysis. That was all based on fruit samples from living trees at Kahanu Garden [a branch of the National Tropical Botanical Garden].

With those things under our belt, we were then able to start distributing breadfruit varieties around the world—doing pilot projects starting with about five chosen varieties that could be distributed.

In turn, that enabled us to start a very active program in 2010, to really promote breadfruit in Hawai’i in a big way—because its use had really declined around here. Hawai’i didn’t have a lot of types of breadfruit left, really.

We started with breadfruit festivals, then breadfruit cookoffs—the idea was to have consistent outreach programs to bring together a rather unlikely collection of people: chefs, cultural practitioners, artisans, horticulturists, forestry people, churches, schools, you name it. We had workshops and festivals around breadfruit, along with fact sheets, coloring books, recipes, and little planting guides to accompany those trees.

And then—about 2012 to 2015—the Institute got a major grant and we were able to distribute more than 10,000 breadfruit trees throughout Hawai’i for free, working with about 200 organizations statewide. We went to every island we could and distributed those trees, with the goal of getting as many as possible into backyards and community gardens and farms as possible.

Then we came to the point where we said to ourselves: “Now that you’ve got all these trees in the ground, and you have all this fruit, what are you going to do with it?” So now we’re getting more into what do you do with breadfruit, how do you make flour from it, how do you store and cook it—all those kinds of things. And this was mirrored in other places to some extent, like the Caribbean.

Drollette: That’s great, but what are the advantages of breadfruit over other crops? What if I was to play devil’s advocate for a moment and say: “Why can’t you just eat Spam and French fries…”

Ragone: You probably wouldn’t do too well.

It’s important to have a diet that is as diversified, wholesome, and unprocessed as possible.

If you look at the health problems that have come up in the Pacific Islands from adopting non-traditional diets—especially junk food—they’re echoed in what you see in the United States, Canada, Europe, and most of the rest of the world. For at least the past 30 years, we’ve been seeing the same kind of health problems, related to our bad diets: higher levels of obesity, cholesterol, and blood pressure.

We’re trying to help change that, by helping people in the Pacific Islands raise food in their own backyards that is easy to grow and nutritious.

And it saves money to boot. We import 50 million pounds of potato into Hawai’i every year; it’s a little-publicized fact that Hawai’i imports 85 to 90 percent of its food. Now, it’s been estimated that for every 10 percent increase in local agricultural food production, the state saves $300 million. I mean, there are some phenomenal figures available in the Hawai’i Department of Agriculture.[7]

And it ties into the bigger picture, which is truly regenerative agriculture.

Drollette: What does the word “regenerative” mean to you as a scientist?

Ragone: That’s a phrase that’s been misused and mis-applied to a lot of things; in a way it’s become a handy buzzword to use to make anything sound good—such as “regenerative tourism.”

But it has its origins in a very firm grounding.

The basic idea is that regenerative agriculture means that there are no external inputs other than planting material—and possibly a bunch of mulch or wood chips, but not too much. The goal is to produce a lot of biomass to go back into the ground and build the soil—to have a living, healthy soil. And then everything grows from that. It’s regenerative because of the fact that it’s a system where pretty much all the inputs are created within the system itself. In that regard, it’s a lot like agroforestry—a method of farming that integrates trees, shrubs, and other plants with crops and animals in ways that provide economic, social, and environmental benefits.[8]

Another way to think of it is that this approach is the opposite of a monoculture. It’s the opposite of farming practices where people inject lots of insecticides, pesticides, fertilizers, and materials like that.

The result is that you don’t wind up with hundreds or thousands of acres of all the exact same species; instead, it’s mixed as much as humanly possible. So, you wind up with a portfolio of different plants with different lifespans, with different end-uses, that can work well together on the land: timber trees, nut trees, breadfruit, and mango up above, with vegetables, taro, and similar other plants in the understory.

It’s the difference between having 100 acres of one species, or 50 plots of two-acres apiece that have all kinds of diverse species mixed in.

Drollette: What challenges does breadfruit face? My understanding is that with climate change, the oceans not only rise, but they get warmer, saltier, and more acidic. How do these changes affect breadfruit trees—are they under threat?

Ragone: From what we’ve found out from traditional practitioners, there actually are some varieties that are more salt-resistant than others—certain atolls in Micronesia come to mind. Meanwhile, other varieties may be more prone to saltwater intrusion but better producers. Still other varieties may more easily succumb to inundation from the really high tides that have been coming more and more.

That’s another big area of research that we want to do; all we’ve done so far is kind of a preliminary assessment.

But yes, some of the varieties of breadfruit trees are at risk—which is where local indigenous knowledge comes in. Consequently, it’s vital to tap into that knowledge, and to save it.

I’ll give you a good example, from when I was doing fieldwork in the dual islands of Samoa. When I was there, I met with a guy who was very knowledgeable about traditional forms of farming and fishing and indigenous practices in general—not just exclusively breadfruit but traditional ways of getting food. He was heavily involved in projects such as re-creating traditional fishing methods.

Anyhow, when he went with me to look at some breadfruit trees in this little village, he could immediately differentiate between 16 different varieties of breadfruit.

Later, I went through that same village again, but this time with a younger woman who was an agricultural extension agent. And she could only differentiate a handful—about the same level that I could at the time—and they were all only the ones that are really deeply, glaringly different. But all the other varieties that he knew about and showed me, she just lumped them all together.

Drollette: From your biography page on the Institute’s website[9], it sounds like you’ve traveled to quite a few islands to collect information from folks like that person in that village in Samoa?

Ragone: I conducted fieldwork on 50 different islands, as part of what people call “ethnobotany.” I was trying to purposely collect as many varieties as I could, with all the associated information about each of them. And I subsequently went back to some of those same islands years later—sometimes more than once—to focus more on traditional uses and food preparation.

I wanted to fill in the blanks about the food aspects: How they processed it, how they first stored it, and how they prepared it—steamed, roasted, boiled, fried, grilled, fermented, whatever.

Drollette: What’s next?

Ragone: Well, I became emeritus in July 2022. And I went on a six-month sabbatical to figure out what I wanted to do going forward; as a result, I decided that I wanted my main focus to be to go through 40 years of field notes and journals about plant collecting, plus information that I had assembled exclusively about breadfruit. I documented over 500 individual trees in the Pacific, and I have interviews with people—both structured and unstructured interviews—about breadfruit and variety. So I have this wealth of handwritten information that I compiled, that I and an assistant are putting into a Word document.

I bet there are over 1,000 pages that I now need to proofread and go through the originals to correct the content. In addition to that, there’s all the publications, resource materials, and photocopies of other original source materials out of the University of Hawai’i library, that even now is not digitally available. There’s also the image collection that I compiled—both photos and videotape—about traditional uses and practices of breadfruit. We’re systematically organizing them and going through them with the hope of writing a book that could be used as a kind of advisory to the direction of the institute going forward.

So, for me personally, that’s what I’m doing. As for the Institute, the regenerative agroforestry project is a big component—as well as conservation of the collection, and how to continue to duplicate and share that collection.

Drollette: What attracted you to studying breadfruit in the first place?

Ragone: I was doing my master’s in horticulture at the University of Hawai’i, in their Pacific Island study program, and I had to choose a crop to write about for my paper. I knew nothing about breadfruit at the time, but I knew I was interested in traditional tropical fruits. That was the initial germ of the idea. And then as I went along, I learned how crucial this fruit used to be—I read a paper written in the 1920s that talked about how important breadfruit had been in the Pacific, and how so many varieties were at risk of disappearing at the time.

And then I read almost verbatim the same thing, written right after World War II, that was, if anything, more dire. And I thought: “Well, that’s what I’m gonna do—I’ll study and collect breadfruit varieties.”

[1] The International Potato Center was founded in Lima, Peru, in 1971 as an R&D organization with a focus on potatoes, sweet potatoes, and other Andean roots and tubers.

[2] The geographical region known as Micronesia lies in the western part of the Pacific, about 5,945 kilometers (3,223 miles) from the islands of Hawai’i. Micronesia contains about 2,100 islands—part of which includes the Marshall Island chain, where many atomic bomb tests were conducted on atolls such as Bikini and Enewetak. There are efforts by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) to repopulate at least one of the islands, Rongelap, adjacent to the bomb test sites. But first, the organizers wanted to re-forest Rongelap using small breadfruit plants propagated and shipped from the Breadfruit Institute, under LLNL’s “Marshall Islands Program.” Ragone said, “Last I heard, as of 2019—in other words, immediately pre-COVID—the plants were in the ground, and they were starting to fruit.”

[3] Across much of the Pacific, people now consume as many soft drinks and junk food, if not more, as locally caught fish and vegetables—a phenomenon noted by commentators from sociologists and historians to travel writers, including Paul Theroux in his travelogue The Happy Isles of Oceania: Paddling the Pacific. Some observers have traced the rise of this profound change in diet to the abundance of canned meat products and other canned goods that accompanied the US Navy and US Army as they island-hopped their way across the Pacific; others think there may be a connection to the so-called “Cargo Cults” that sprang up at war’s end. This preference for junk food is not restricted to remote islands; to this day, in heavily populated Honolulu, the local McDonalds chain serves Spam on the menu. More information can be found in articles such as Vice magazine’s “The History Behind Why Hawaiians Are Obsessed With Spam.”

[4] Some of the Breadfruit Institute’s many printable resources and videos, in English and Hawaiian, can be found online at the Breadfruit Institute’s “Resources” page.

[5] For more, see Smithsonian Magazine article “Captain Bligh’s Cursed Breadfruit: The biographer of William Bligh—he of the infamous mutiny on the Bounty—tracks him to Jamaica, still home to the versatile plant” and Current Biology’s “Linking breadfruit cultivar names across the globe connects histories after 230 years of separation.”

[6] See “The Plight of the African Violets.”

[7] See Increased Food Security and Food Self-Sufficiency Strategy.

[8] For more, see “Breadfruit Agroforestry.”

[9] See the Breadfruit Institute’s “Staff” page.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Pacific Islands, agroforestry, breadfruit, climate change, food, locally grown, regenerative agriculture, sustainable

Topics: Climate Change, Special Topics