RFK Jr.’s presidential ambitions may have fallen short, but his anti-vax beliefs are winning in many statehouses

By Matt Field | September 5, 2024

RFK Jr.’s presidential ambitions may have fallen short, but his anti-vax beliefs are winning in many statehouses

By Matt Field | September 5, 2024

A leaked video from July shows Robert F. Kennedy Jr. taking an important call. Donald Trump, fresh from surviving an assassination attempt, was on the other end of the line—allegedly, on the night before winning the Republican Party’s nomination. The call could have been between any two cranks spewing forth on the long-debunked theory that connects childhood vaccines to autism—on a fringe podcast, perhaps, or, maybe, on some dark corner of the web.

It wasn’t.

One man on the call stood a strong chance of becoming the next US president and the other was the country’s most famous anti-vaxxer. “And then you see the baby all of a sudden begin to change radically,” Trump told the man he called Bobby. “I’ve seen it too many times. And then you hear that it doesn’t have an impact, right?”

Since Kennedy announced a presidential run in 2023, he’s often registered in the double-digits in opinion polls. Those aren’t bad numbers for an independent—and some reporting suggested Trump was seeking Kennedy’s endorsement when the pair met soon after the call (O’Brien and Weisman 2024). Public health experts worried that Kennedy—who has tirelessly pushed conspiratorial anti-vaccine views through articles, movies, and social media for years—would do the same thing on the presidential campaign trail, using his golden political name and the media attention it would garner as a vehicle to raise the profile of the anti-vax movement (Romero 2023). But the July call with Trump was further evidence of a more troubling truth: Kennedy and his once-fringe anti-vaccine views have already broken through. If not yet mainstream, they are well represented in the halls of political power.

The COVID pandemic, with tens of millions of people in the United States stuck at home—and presumably with ample time to read up on virology, vaccine development, and public health— provided the anti-vax movement with a captive audience and gobs of cash. Groups like Kennedy’s Children’s Health Defense and three other major organizations that promote anti-vaccine sentiment or scientifically unsupported treatments for COVID raised a combined $118 million in donations between 2020 and 2022 (Weber 2024). In 2022, Kennedy’s group and another organization, known as Informed Consent Action Network, raised, respectively, eight times and four times what they head in the year before the pandemic began, according to a Washington Post article in February 2024 (Weber 2024). The anti-vaccine organizations flooded the internet with vaccine misinformation and at the same time gave themselves hefty pay increases. (Kennedy’s salary of $510,000 in 2022 was double what he earned in 2019.) Children’s Health Defense started an online TV network. The Informed Consent Action Network spent $6 million on educational programs in 2022, according to the Post article.

But their efforts weren’t all digital. The movement expanded its work: organizing constituents, helping to elect vaccine-skeptical lawmakers, and visiting statehouses to talk to them. In several cases, the officeholders in turn have been able to push anti-vaccine bills further along in the legislative process than they otherwise might have been able to in the past, sometimes all the way into state law.

Much of the movement’s growing power has come through ties with the political right wing. Though he comes from a family whose last name is a political icon of the left, Kennedy has struck a chord with many Republicans—as the Trump call illustrated. He has talked with state legislators in Louisiana. At the invitation of House Republicans, Kennedy has testified in Congress, where he and lawmakers discussed so-called “natural immunity,” or immunity gained through infection instead of vaccination (Bazail-Eimil 2023). He’s a popular guest on Fox News and other right-wing media (Allison, Isenstadt, and Gibson 2024). And he’s leaned into the Republican war on the former director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease Anthony Fauci, who had a role in funding virology research in China before the pandemic. (Kennedy’s The Real Anthony Fauci, according to its Amazon sales page, purports to show how Fauci and other so-called “corrupt evil-doers” controlled the media, intelligence agencies, the government, and scientists “to flood the public with fearful propaganda about COVID-19 virulence and pathogenesis, and to muzzle debate and ruthlessly censor dissent.”)

Indeed, Republicans have pushed much of the anti-vaccine legislation that’s passed in recent years, including in Louisiana, Montana, and Idaho (Montana Free Press 2024; Roth 2023). The anti-vaccine movement has made its clearest inroads with these politicians.

The top health official in Florida, Joseph Ladapo, who once urged a halt to COVID vaccines, overruled standard operating procedure and let parents decide whether to send their unvaccinated children to a school experiencing an outbreak of measles, echoing the themes of parental rights and health freedom that have become popular on the right (Field 2023a).

Ladapo’s boss, Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis, once said that he would appoint Kennedy to a position in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) or the Food and Drug Administration (Frankel 2023). While polls show generally strong support for routine vaccinations, 42 percent of Republicans said in a 2023 survey that whether to get school vaccinations should be a parent’s choice, compared to just 14 percent of Democrats. The same survey reported that 70 percent of Republicans said they were unvaccinated against COVID, with 20 percent of Democrats saying the same (Funk 2023).

The roots of vaccine polarization

In trying to pinpoint when the issue of vaccines became politically polarized, some observers point to a 2014-2015 Disneyland measles outbreak that spread across state lines and into Mexico and Canada. This one outbreak alone caused nearly 150 infections from the sometimes overlooked but dangerous virus (CDC 2015). A significant portion of the infected were unvaccinated—a handful because they were too young, but many out of preference.

Though a liberal stronghold, when California sought to do away with nonmedical exemptions to school vaccine requirements in 2015, partly as a reaction to the measles outbreak months earlier (Martinez and Watts 2015), lawmakers faced a harsh backlash—though the effort ultimately succeeded. During the fight over the bill, however, observers noticed an evolution in the anti-vaccine movement, one bringing it more in line with conservative doctrine.

Online disinformation expert Renee DiResta and data scientist Gilad Lotan found that after the California effort, accounts on Twitter (now X) that had once focused on false conspiracy theories—usually about the CDC concealing damaging research about a link between vaccines and autism—now undertook a new line of attack. “Instructions to the group now focus on hammering home traditionally conservative ‘parental choice’ and ‘health freedom’ messaging rather than tweeting about autism and toxins,” the pair wrote in Wired in 2015 (DiResta and Lotan 2015). Not coincidentally, the new language dovetailed nicely with that used by right-wing hardliners.

Through activism around the California bill, as well as the formation of new anti-vaccine political action committees, anti-vax groups were fast moving beyond their left-leaning base—one which had focused on what it considered “natural living” and which had long made up a large part of their core support. Now, the anti-vax groups were moving into alliances with right-wingers. “For anti-vaccine activists, this mutualism enabled access to money, political influence, and broader audiences. For the libertarian right, it provided a cohort of politically active Americans whose support could be directed towards other causes,” DiResta and others wrote in The Lancet in 2023 (Carpiano et al. 2023).

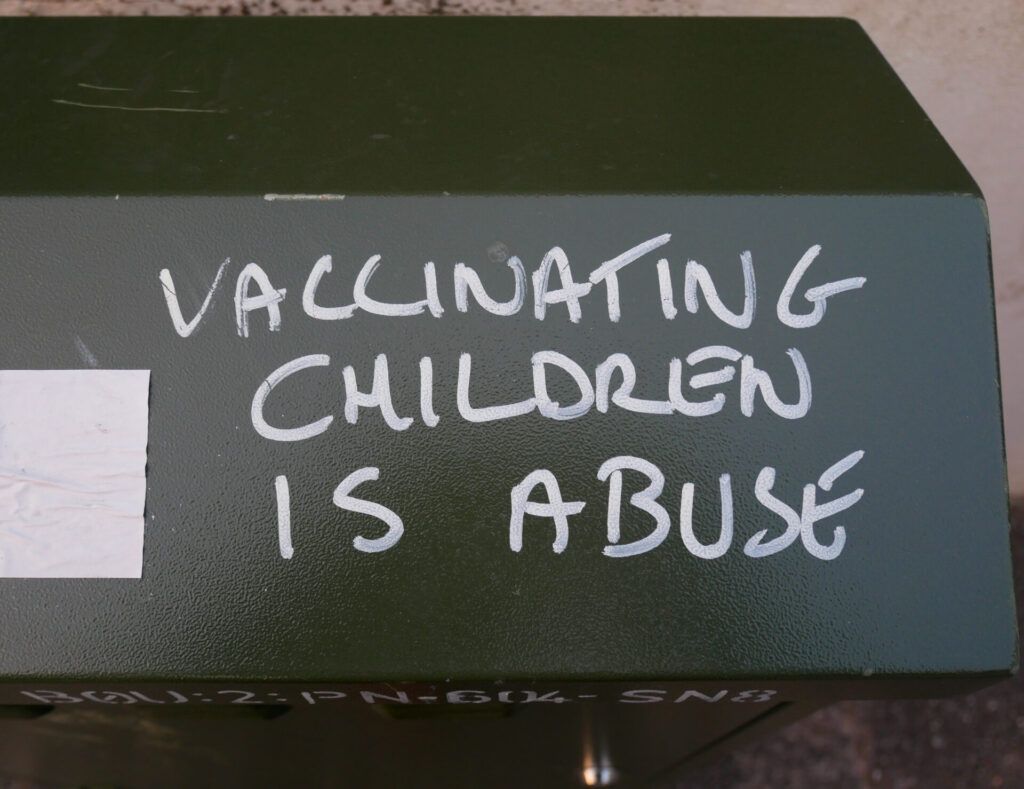

And the shift by the anti-vaccine movement toward conservatively branded language appears to have registered. Many politicians now pushing anti-vaccine legislation object, in fact, to being tagged as anti-vaccine. Beryl Amedee, a Louisiana legislator who has sponsored several anti-vax bills, told The Washington Post in December 2023 that she wasn’tanti-vaccine, but rather that she was “pro everyone having the opportunity to make their own health decisions” (Weber 2023).

But their objections to the “anti-vax” label mask the true effect of the bills elected officials like Amedee have been proposing.

One common type of anti-vax bill seeks to expand exemptions to school vaccine requirements or create new ones if they don’t already exist—for example, a religious exemption in a state that only has medical exemptions. Experts worry that when exemptions are made easy, more parents will choose them, increasing the risk of an outbreak. In 2018, a study showed that of the 18 states that allowed “philosophical belief” exemptions at the time, the rate of requests had increased since 2009 in 12 of them (Olive et al. 2018).

According to the CDC, during the 2019-2020 school year, 95 percent of kindergarteners had received measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR), polio, tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (whooping cough), and varicella inoculations (Seither et al. 2023). This vaccination percentage was enough to generate what researchers refer to as “herd immunity,” in which viruses like measles can’t easily spread, protecting those unable—or unwilling—to get vaccinated (Mathis et al. 2024). The next year that figure was 94 percent. During the 2021-2022 and 2022-23 school years, the rate fell again to 93 percent as exemptions rose to 3 percent. Some 250,000 kids were at risk for measles, scientists with the agency reported in 2023.

In 2019, at least 20 states weighed bills to expand access to exemptions from required school vaccines—up from four states the year before (Lou and Griggs 2019).

The view from the statehouse

Pre-COVID, observers viewed most anti-vax legislation as doomed to die on the statehouse floor. And historically many anti-vaccine bills have failed. “What typically happens is an anti-vaccination activist will convince a legislator to float a bill based on misinformation or faulty science, and once the bill hits the relevant committee, they realize the bill is going to hurt public health,” Sean O’Leary, a doctor in Colorado who followed legislation, told CNN in 2019.

In many cases, legislators with positive views on vaccines—or at least, a pro-vaccine governor—stood in the way. One example of this occurred in Arizona.

In 2019, in the midst of a large measles outbreak in Washington state, Arizona legislators held a hearing with the National Vaccine Information Center—an established anti-vaccine group on anti-vaccine legislation (Stone 2019). Lawmakers passed three bills through committee to make it easier to get exempted from school vaccine requirements, require patients to receive documents that could discourage them from being vaccinated, and require doctors to offer patients an unreliable test to gauge whether they need a vaccine (Innes 2019; Reiss 2019). But Gov. Doug Ducey, a Republican like the legislators who had pushed the bills in committee, vowed to veto them, declaring himself “anti-measles.”

Vaccine exemption bills don’t shoulder all the blame for increases in the rates of exemption requests. In Arizona, where the Republican-led effort to ease exemptions failed, the rate of kindergarten exemption requests still rose to 6.8 percent in 2022 (Duda and Boehm 2023).

But the political picture appears to have grown more promising for the anti-vaccine movement. Although lawmakers saw many of the hundreds of vaccine-related bills they introduced fail on the legislative floor since the beginning of the pandemic, the anti-vaccine movement seems to be notching some successes—or at least getting further along in the political process (Roth 2023).

Back in 2019, when a West Virginia Republican introduced a bill to allow for religious exemptions to school vaccines, the bill died unceremoniously in a committee (Suarez 2019). But in 2024, when Republicans again introduced a bill to allow a subset of schools to set their own vaccine policies (such as parochial schools), the measure passed. The state’s Democrat-turned-Republican governor, Jim Justice, vetoed it, however, citing the role of the state’s high vaccination in protecting its citizens against diseases like measles.

Supporters of the failed anti-vaccine bill promised they would try again (Field 2024b); they just might succeed the next time. Justice’s likely Republican successor as governor, Attorney General Patrick Morrisey, filed a brief in court to support plaintiffs seeking to force the state to adopt a religious exemption, an indication of how he views the issue (Baker and Lynch 2023).

In Louisiana, the anti-vax movement has achieved outright success. Republican Rep. Kathy Edmonston told States Newsroom that under the state’s previous Democratic governor, John Bel Edwards, her vaccine bills had died in the legislature or been vetoed (Chatlani 2024). But this summer, new Republican Gov. Jeff Landry—who as State Attorney General once invited Kennedy to talk with lawmakers—signed her bill expanding information on exemptions, one of several measures championed by anti-vaccine proponents that passed the legislature (Woodruff 2024).

The showing was a reflection of the growing electoral clout of the anti-vaccine movement since the pandemic, gained through endorsements and other forms of political support for candidates and lawmakers.

In 2023, 29 of the 40 candidates endorsed by anti-vaccine nonprofit Stand for Health Freedom won election at the state level in Louisiana. The Informed Consent Action Network, which creates “model bills” for anti-vaxxers to propose in their statehouses, even saw one of them—a bill requiring that unvaccinated students not be treated differently than vaccinated ones—make it into law in the state (Informed Consent Action Network Legislate n.d.). Jennifer Herricks, the founder of the pro-vaccine group Louisiana Families for Vaccines, said the new laws in Louisiana may not be detrimental to state vaccination rates, which have been dipping since the pandemic. Many of them don’t depart significantly from existing policy, she said. For example, Louisiana already provided for exemptions from routine school vaccines, and the new anti-vaccine law simply requires schools to communicate a bit more about exemptions than in the past.

But overall Herricks believes that anti-vax groups have adopted an incremental approach to achieving their goals.

“Especially right after the pandemic, we saw a lot of bills that would have brought a lot of extreme changes, and even with all of the boom that they saw post pandemic, those bills still didn’t get anywhere in most states,” Herricks said. “But I think now what we’re seeing is they’ll walk that back a little bit and instead of trying to take a mile, they take an inch. And I think that we’re going start to see them kind of chip away at public health and existing vaccine policies little by little.”

The pandemic windfall of attention and resources has allowed anti-vax groups to “communicate better with legislators,” Herricks said. The groups, she said, have representatives at nearly every committee hearing dealing with vaccines.

Her group is part of a national organization called Safe Communities Coalition, which supports pro-vaccine legislation and lawmakers (Safe Communities Coalition n.d.).

Even in places where legislative progress has been elusive, anti-vaxxers have still made significant gains through the courts. In Mississippi, one of the few states that had no nonmedical exemptions, Republican lawmakers tried six times in 2023 to add a religious exemption to school vaccine requirements (NCSL 2024). Each failed. But where the policy failed in the legislature, national and local anti-vaccine activists, with an assist from the Republican attorney general, won an exemption in federal court. The Informed Consent Action Network funded a lawsuit involving plaintiffs who said they couldn’t send their kids to Mississippi schools because of their religious exemptions to the state’s vaccine requirements (Pettus 2023).

Mississippi, a state where the exemption rate had been among the lowest in the nation, soon saw a rapid increase in the number of requests for religious exemptions: over 2,200 in the first few months of the new policy, with 500 more medical exemptions. (The state’s top public health official told NBC News that if the state can keep exemptions to 3,000 or less, Mississippi could keep outbreaks at bay.) Del Bigtree, founder of the Informed Consent Action Network, promised a multi-million-dollar legal attack on vaccine requirements in other states, like California and Connecticut, that have no non-medical exemptions (Zadrozny 2023).

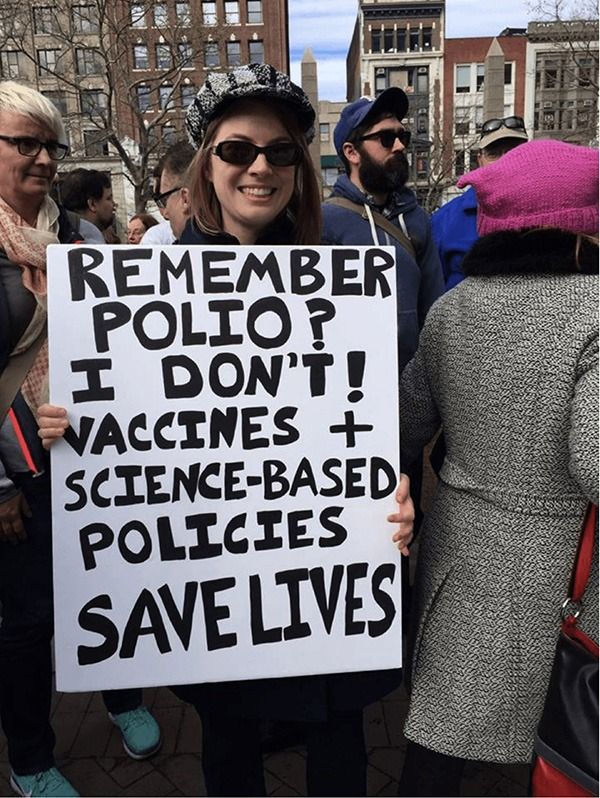

It’s frequently pointed out that vaccines are a victim of their own success. The reason some people want an end to mandatory childhood polio vaccines is perhaps because they don’t remember the fear of contracting polio, with symptoms like paralysis that sometimes left victims in the dreaded “iron lung” breathing machine. Indeed, many of the diseases that school vaccines guard against are so uncommon in the United States that one might have to turn to Google to figure out what they are.

Rubella? It’s a viral disease that can cause a fever, a runny nose, and other mild symptoms, oh and arthritis in 70 percent of women (CDC 2024). When a vaccine was introduced in 1969, cases went from about 50,000 a year to six in 2020 (Mayo Clinic 1969).

Diptheria? It’s a bacterial disease that’s “extremely rare” in the United States, thanks to the vaccine, says the Mayo Clinic. It’s fatal 5-10 percent of the time, but can cause cardiac, respiratory, and nerve problems even when it’s not (Mayo Clinic 2023).

In recent years the anti-vax movement and its allies in the statehouses has begun to chip away at the country’s immunity to these diseases, building off the energy of the anti-mask, anti-COVID vaccine, anti-lockdown days of the pandemic. Dorit Reiss, a University of California San Francisco law professor who tracks the anti-vax movement predicted that ironic result. “I was saying to people, this could go either way. Either the pandemic will remind people why public health is important or the anti-vaccine movement will have a chance to reach a much broader audience,” she told me. “Both things kind of happened.” Polls show most people still support vaccines, and many officials, doctors, scientists, and activists aim to keep it that way. But as the Trump-Kennedy call hinted, the wealthy and connected anti-vax movement is well positioned for even greater power in November. The “anti-measles” crowd almost certainly has a fight on its hands.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: 2024 election, Jr., Robert F. Kennedy, anti-vax, presidential election, public health, state governments, vaccination

Topics: Special Topics