Russian nuclear weapons, 2025

By Hans M. Kristensen, Matt Korda, Eliana Johns, Mackenzie Knight | May 13, 2025

Russian nuclear weapons, 2025

By Hans M. Kristensen, Matt Korda, Eliana Johns, Mackenzie Knight | May 13, 2025

Russia is in the late stages of a multi-decade-long modernization program to replace all of its Soviet-era nuclear-capable systems with newer versions. However, this program is facing significant challenges that will further delay the entry into force of these newer systems. In this issue of the Nuclear Notebook, we estimate that Russia now possesses approximately 4,309 nuclear warheads for its strategic and non-strategic nuclear forces. Although the number of Russian strategic launchers is not expected to change significantly in the foreseeable future, the number of warheads assigned to them might increase. The significant increase in non-strategic nuclear weapons that the Pentagon predicted five years ago has so far not materialized. A nuclear weapons storage site in Belarus appears to be nearing completion. The Nuclear Notebook is researched and written by the staff of the Federation of American Scientists’ Nuclear Information Project: director Hans M. Kristensen, associate director Matt Korda, and senior research associates Eliana Johns and Mackenzie Knight.

This article is freely available in PDF format in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ digital magazine (published by Taylor & Francis) at this link. To cite this article, please use the following citation, adapted to the appropriate citation style: Hans M. Kristensen, Matt Korda, Eliana Johns, and Mackenzie Knight, Russian Nuclear Weapons, 2025, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 81:3, 208-237, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2025.2494386

To see all previous Nuclear Notebook columns in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists dating back to 1987, go to https://thebulletin.org/nuclear-risk/nuclear-weapons/nuclear-notebook.

Russia is nearing the completion of a decades-long effort to replace all of its strategic and non-strategic nuclear-capable systems with newer versions. But despite Moscow’s continued rhetorical emphasis on its nuclear forces, commercial satellite imagery and other open sources indicate that elements of Russia’s nuclear modernization are proceeding much more slowly than planned: Upgrades to intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and bombers face significant delays, and the “significant” increase of Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons that US Strategic Command (STRATCOM) predicted five years ago has yet to materialize (Richard 2020, 5).

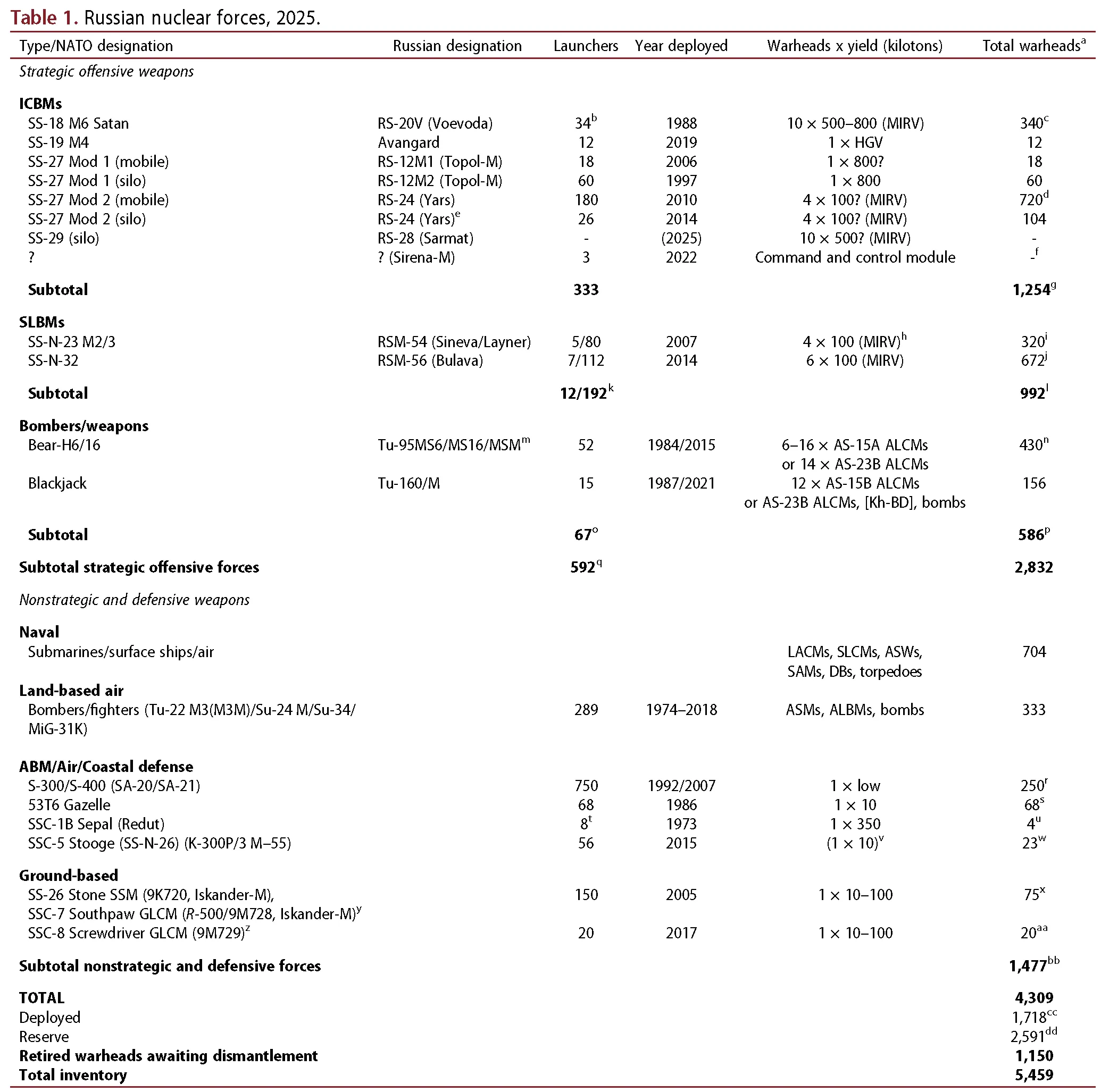

As of early 2025, we estimate that Russia has a stockpile of approximately 4,309 nuclear warheads assigned for use by long-range strategic launchers and shorter-range tactical nuclear forces. This is a net decrease of approximately 71 warheads from last year, largely due to a change in our estimate of warheads assigned to non-strategic nuclear forces. Of the stockpiled warheads, approximately 1,718 strategic warheads are deployed: about 870 on land-based ballistic missiles, about 640 on submarine-launched ballistic missiles, and possibly slightly over 200 at heavy bomber bases. Another approximately 1,114 strategic warheads are in storage, along with about 1,477 nonstrategic warheads. In addition to the military stockpile for operational forces, a large number—approximately 1,150—of retired but still largely intact warheads await dismantlement, for a total inventory of approximately 5,459 warheads[1] (see Table 1).

Russia’s nuclear modernization program appears motivated in part by the Kremlin’s strong desire to maintain overall parity with the United States and to maintain national prestige. The program also seems to seek compensation for inferior conventional forces and the Russian leadership’s long-held conviction that the US ballistic missile defense system constitutes a real future risk to the credibility of Russia’s retaliatory capability. Throughout its war in Ukraine, Russia has conducted a series of missile strikes using long-range dual-capable precision weapons, such as Kh-101 air-launched cruise missiles (the nuclear version is called Kh-102), sea-launched 3 M–54 Kalibr cruise missiles, 9-A-7760 Kinzhal ballistic missiles, air-launched Kh-22 (AS-4 Kitchen) cruise missiles, and ground-launched Iskander missiles (Interfax 2022a, 2022b; Reuters 2023b). Additionally, the United Kingdom Ministry of Defence has released several intelligence reports identifying that Russia has used de-nuclearized Kh-55 (AS-15 Kent) cruise missiles in Ukraine (United Kingdom Ministry of Defence 2022, 2023). Yet the performance of Russian weapons and its military has been much less effective than what experts had assumed before the war. It is potentially possible that some of these factors could also affect the performance of Russia’s nuclear forces.

Russia’s nuclear modernization programs—combined with frequent explicit nuclear warnings and threats against other countries in the context of its large conventional war in Ukraine—contribute to uncertainty about the country’s long-term intentions and have generated a growing international debate about the nature of its nuclear strategy. These concerns, in turn, have led to increased defense spending, nuclear modernization programs, and political opposition to further nuclear weapons reductions in Europe and the United States.

The New START treaty expires in early February 2026. After that, if Russia decided to exceed the central limits of the treaty, it could theoretically upload hundreds of warheads onto its deployed delivery systems, potentially increasing its deployed nuclear arsenal by up to 60 percent (Korda and Kristensen 2023). How quickly this could be achieved depends largely upon the weapon system: Bombers could be armed in a matter of hours or days, whereas a complete warhead upload of the submarines could take months and changing the warhead configuration on each ICBM could take several years.

Research methodology and confidence

The analyses and estimates made in the Nuclear Notebook are derived from a combination of open sources: (1) state-originating data (e.g. government statements, declassified documents, budgetary information, military parades, and treaty disclosure data); (2) non-state-originating data (e.g. media reports, think tank analysis, and industry publications); and (3) commercial satellite imagery. Because each one of these sources provides different and limited information that is subject to varying degrees of uncertainty, we crosscheck each data point by using multiple sources and supplementing them with private conversations with officials whenever possible.

Analyzing and estimating Russia’s nuclear forces is becoming an increasingly challenging endeavor, in part due to President Vladimir Putin’s decision in 2023 to suspend Russia’s participation in New START, the bilateral US-Russia treaty that requires both countries to exchange data about their respective numbers of deployed strategic warheads and launchers. New START was a critical node for transparency and allowed analysts to work backward from the aggregate numbers to estimate the breakdown of Russia’s deployed strategic forces.

In the most recent New START data, as of September 1, 2022, Russia was listed as having 1,549 deployed warheads assigned to 540 strategic launchers (US Department of State 2022b). Since then, Russia has not released any data but appears to remain below the limits. Our current estimates of strategic nuclear forces are relatively close to the 2022 data. However, the New START numbers differ from the estimates presented in this Nuclear Notebook because the treaty’s counting rules artificially attribute one warhead to each deployed bomber, even though Russian bombers do not carry nuclear weapons under normal circumstances. The treaty also does not count weapons stored at bomber bases as “deployed.” The Nuclear Notebook does count these weapons as deployed when they can quickly be loaded onto the aircraft because this represents a more realistic picture of the deployment status of weapons.

Given that Russia has not provided this data to the United States since September 2022, it is increasingly difficult to compile a comprehensive picture of Russia’s nuclear force structure. Although Putin has repeatedly stated that Russia would stay below the overall limits of New START, the January 2025 US State Department compliance report noted that “The United States is unable to make a determination that the Russian Federation remained in compliance throughout 2024 with its obligation to limit its deployed warheads on delivery vehicles subject to the New START Treaty to 1,550, due to Russia’s proximity to the limit as of its last update and failure to fulfill its obligations with respect to the Treaty’s verification regime” (US Department of State 2025b). The report also noted that “The United States assesses with high confidence that Russia did not engage in any large-scale activity above the Treaty limits in 2024,” but added that “Russia was probably close to the deployed warhead limit during much of the year and may have exceeded the deployed warhead limit by a small number during portions of 2024” (US Department of State 2025b).

To maintain confidence in our estimates, we supplement this historical treaty data and recent official statements with Russian state and non-state media news releases, industry reports, translations of strategic documents, videos published by the Russian Ministry of Defence, and other materials. These types of secondary sources often contain valuable information about the progress of Russian weapons procurement programs, such as the schedule for the commission or decommission of various weapon systems, the number of units of each system expected to be procured, and the technical specifications of these systems. Yet, this public data is getting more difficult to access because the Russian state cut off internet access to several previously accessible websites after it invaded Ukraine.

In addition to these materials, high-ranking Russian military leaders typically provide end-of-year interviews to Russian state media about the current situation of their respective services. On some occasions, the interviewees disclose some specific details about the number of new units of each weapon system that were commissioned during the year, as well as other relevant annual updates. Military leaders also sometimes share their goals for the following year, which can then be used as a research guideline for analysts to measure the progress of Russia’s nuclear modernization programs.

To perform this analysis, we frequently use various sources of commercial satellite imagery to observe and document highly granular changes to Russia’s nuclear forces. Satellite imagery makes it possible to identify air, missile, and navy bases, as well as potential nuclear weapons storage facilities. Satellite imagery has been particularly instrumental in monitoring construction and updates at critical nuclear-related facilities, including ICBM silos, air and submarine bases, warhead storage areas, and others. By analyzing the observable strategic force structure, we can offer a well-reasoned estimate of Russia’s strategic nuclear forces, although as we get further away from New START disclosures, the relative confidence in these estimates is decreasing.

In contrast, it is even more difficult to develop a comprehensive picture of Russia’s non-strategic nuclear weapons. Nearly every Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons delivery vehicle is dual-capable—that is, it can be used in both nuclear and conventional strike roles. This means that counting every Russian non-strategic delivery vehicle as being assigned a nuclear warhead would likely yield an inflated estimate. In addition, many of Russia’s non-strategic nuclear weapons are several decades old, and it is highly uncertain how many of these weapons remain active and how many are slated for retirement and will be replaced with newer versions. The already difficult picture is further complicated by the fact that Russia has significantly more non-strategic weapons than any other country, compounded by a lack of verifiable public information about these weapons. The US government has for several years estimated that Russia has between 1,000 and 2,000 non-strategic nuclear weapons, significantly fewer than the 2,000–4,000 a decade-and-a-half ago (Kristensen 2019); however, this still represents a sizable error margin. Our estimate of approximately 1,500 non-strategic nuclear weapons falls within this range and attempts to establish a more specific overview of Russia’s non-strategic and defensive forces (see Table 1). However, given that our efforts to analyze Russia’s non-strategic nuclear forces are limited to analysis of satellite imagery, current and historical government documents, news sources, and other non-governmental sources amid a lack of verifiable public data, this specific estimate does not come with a high degree of confidence.

In addition, it is important to view external assessments with a critical eye, particularly regarding the risk of citation and confirmation bias in which governmental or non-governmental reports continuously reference each other’s claims and estimates—sometimes without the reader knowing that this is occurring. This practice can inadvertently create a cyclical echo chamber effect, which may not necessarily match the reality on the ground and may lead to inflated estimates of numbers and capabilities. This is because the information used in the public debate about Russian weapons numbers mainly comes from the US military, which tends to favor higher worst-case estimates when making threat assessments to inform policy responses.

Despite these difficulties, we maintain a higher degree of confidence in our Russian nuclear force estimates compared with those of other nuclear-armed countries (China, Pakistan, India, Israel, and North Korea) for which official and unofficial information is either scarce, unreliable, or both. However, our estimates about Russian nuclear forces—particularly Russia’s non-strategic nuclear forces—come with a lower degree of confidence than those for countries with greater nuclear transparency (the United States, the United Kingdom, and France).

Russia’s nuclear strategy and its war in Ukraine

Russia last updated its public official deterrence policy in 2024 through an executive order that described explicit conditions under which it could potentially launch nuclear weapons (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation 2024):

- receipt of reliable data on the launch of ballistic missiles attacking the territories of the Russian Federation and (or) its allies;

- employment of nuclear or other types of weapons of mass destruction by an adversary against the territories of the Russian Federation and (or) its allies, against facilities and (or) military formations of the Russian Federation located outside its territory;

- actions by an adversary affecting elements of critically important state or military infrastructure of the Russian Federation, the disablement of which would disrupt response actions by nuclear forces;

- aggression against the Russian Federation and (or) the Republic of Belarus as participants in the Union State with the employment of conventional weapons, which creates a critical threat to their sovereignty and (or) territorial integrity;

- receipt of reliable data on the massive launch (take-off) of air and space attack means (strategic and tactical aircraft, cruise missiles, unmanned, hypersonic and other aerial vehicles) and their crossing of the state border of the Russian Federation.

These conditions were more expansive than those included in the 2020 iteration of the doctrine, which described that Russia could use nuclear weapons in response to an attack with weapons of mass destruction or when “the use of conventional weapons when the very existence of the state is in jeopardy” (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation 2020). This new formulation could be interpreted to have lowered the threshold for the use of Russian nuclear weapons and is likely a result of the evolving East-West nuclear dynamics during the Russia-Ukraine war. Whether, or the extent to which, the Russian military has actually changed its plans for the potential use of nuclear weapons is unclear.

The nuclear signals issued by Putin and other Russian officials throughout the war in Ukraine have prompted questions about where, how, and when Russia might use a nuclear weapon. In particular, it is not clear how broad Russian leaders consider the “territories of the Russian Federation” in the country’s nuclear doctrine: Do “territories” extend to the newly illegally annexed portions of Ukraine? Or are they limited to the internationally recognized borders of the Russian Federation? In addition to Belarus which is explicitly named as a participant in the Union State, which countries are included as Russia’s “allies” that would meet the conditions for a nuclear response? In response to the Western reactions to Russia’s doctrine change, Putin said: “Let me stress once again, so that no one accuses us of trying to scare everyone with nuclear weapons: This is a policy of nuclear deterrence” (Russian Federation 2024a).

Although many Russian officials regularly comment on Russia’s nuclear doctrine, it is believed that only three people—President Putin, Minister of Defence Andrey Belousov, and Chief of the General Staff Valery Gerasimov—possess so-called nuclear briefcases that can be used to authorize the employment of Russian nuclear weapons. Moreover, an order from Putin must be cosigned by one of these two officials before any nuclear weapons can be launched (Ven Bruusgaard 2023). It is possible that Putin himself sees strategic utility in remaining ambiguous about his own views—which, under the current Russian political regime, essentially from the state’s official posture—regarding the conditions under which Russia would use nuclear weapons. At the very least, Russia’s nuclear signaling appears primarily designed to deter the United States and NATO from interfering militarily in the ongoing conflict in Ukraine.

Russian strategic missiles in silos on land and onboard submarines remain on alert with nuclear warheads and ready to launch within minutes. Warheads for non-strategic nuclear forces, in contrast, have been thought to be kept separated from their launchers in central storage depots. However, in a speech to the Defence Ministry Board in December 2024, Putin stated: “It is likewise important to keep non-strategic nuclear forces on constant alert and to continue holding exercises involving their potential use” (Russian Federation 2024a). It is unclear if he was referring to non-strategic launchers or their warheads. Keeping even a portion of Russia’s non-strategic nuclear forces on alert with nuclear warheads would constitute a significant change to the Russian nuclear alert strategy.

In February 2024, House Intelligence Committee Chairman Mike Turner requested the declassification of information concerning an unspecified “serious national security threat” (House Intelligence Committee 2024). The following day, National Security Council spokesperson John Kirby publicly confirmed the threat was related to a “troubling” anti-satellite weapon that Russia is developing (The White House 2024a). At a House Armed Services Committee hearing in May 2024, Assistant Secretary of Defense for Space Policy John F. Plumb said the Pentagon was concerned Russia is developing the ability to “fly a nuclear weapon in space,” which would put vulnerable satellites and other space-based infrastructure at risk (Harpley 2024). If Russia were to place a nuclear weapon in orbit, it would not only violate the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, but it would be a highly destabilizing and unprecedented act.

A possible return to nuclear testing?

In November 2023, Putin signed a bill into law officially withdrawing Russia’s ratification of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), which bans all nuclear detonations (Federal Assembly of the Russian Federation 2023). Russia’s “de-ratification” followed reports that Russia could be preparing to resume nuclear explosive testing at its former test site in Novaya Zemlya. Recent satellite imagery indicates a higher level of activity at the site, including the presence of large trucks, construction cranes, shipping containers, and new construction at several on-site administrative and residential facilities (Lewis 2023). Rear Admiral Andrei Sinitsyn, the head of Russia’s nuclear test site in Novaya Zemlya, said in an interview in September 2024 with the state-run newspaper Rossiyskaya Gazeta that the site is “fully ready” for the resumption of “full-scale testing activities” (Rossiyskaya Gazeta 2024), However, Russian officials have previously stated that they will not resume nuclear testing unless the United States does (Isachenkov 2023; Osborn 2023).

Russian nuclear sharing in Belarus

Between 2022 and 2024, President Putin and Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko appear to have established the infrastructure to forward-deploy Russian tactical nuclear weapons on Belarusian territory. Whether the warheads for those weapons are currently in Belarus is unclear.

In a March 2023 announcement, Putin also specified that Russia had reequipped 10 Belarusian Su-25 aircraft with the ability to deliver nuclear weapons and had transferred dual-capable, road-mobile short-range Iskander (SS-26) launchers to Belarus (Smotrim 2023). The Belarusian brigade base for the Iskander launchers is thought to be in the southern outskirts of Asipovichy, roughly seven miles west of where satellite imagery has shown the construction of a double-fenced security perimeter around a weapons depot—a signature that can also typically be observed at Russia’s nuclear storage areas (Kristensen and Korda 2023). Several open-source clues suggest that Lida Air Base, located only 40 kilometers from the Lithuanian border and the only Belarusian Air Force wing equipped with Su-25 aircraft, is the most likely candidate for Russia’s new “nuclear sharing” mission in Belarus (Korda, Reynolds, and Kristensen 2023).

In late December 2023, Lukashenko stated that Russia had completed its shipments of nuclear weapons to Belarus, and in early January 2024, Belarus updated its military doctrine that reportedly described nuclear weapons “as an important component of preventive deterrence of a potential enemy from unleashing armed aggression” (Associated Press 2023; Belta 2024; Buzin 2024; Knight and Lau 2024).

There are still several unknowns surrounding the status and logistical challenges of deploying Russian nuclear weapons to Belarus. For instance, nuclear weapons storage sites in Russia took much longer to build than the short timeline Putin and Lukashenko announced for storage facilities in Belarus. In addition, personnel from the 12th GUMO—the department within Russia’s Ministry of Defence responsible for maintaining and transporting Russia’s nuclear weapons—would need to be deployed to Belarus to staff the storage site, regardless of whether nuclear weapons are present. This substantial personnel deployment—perhaps up to 100 individuals—would likely require segregated living facilities from those housing Belarusian soldiers, as well as other infrastructure that could take many months to build and would be visible on satellite imagery. Moreover, the storage facility would be unable to receive warheads until all specialized equipment and personnel are in place at the site and along the transport route.

So far, we have not seen conclusive visual evidence to pinpoint where Russian nuclear warheads are being stored and 12th GUMO personnel are deployed in Belarus, if indeed they are in the country at all. The upgraded Cold War-era nuclear weapons storage depot at Asipovichy seems to be the most likely candidate. In December 2024, however, Lukashenko stated that Belarus is currently hosting “dozens” of Russian nuclear warheads (Associated Press 2024b). Putin noted that Russia’s new Oreshnik intermediate-range ballistic missile—used for the first time in operation in Ukraine in November 2024 (see section “Ground-based nonstrategic nuclear weapons”)—could be deployed to Belarus in the second half of 2025 and that Belarus would play a role in nuclear targeting (Associated Press 2024b).

Intercontinental ballistic missiles

Russia’s Strategic Rocket Force currently deploys several variants of silo-based and mobile ICBMs. The silo-based ICBMs include the RS-20 V Voevoda (also known by the NATO designation SS-18), the RS-12 M2 Topol-M (SS-27 Mod 1), RS-24 Yars (SS-27 Mod 2), and the Avangard (SS-19 Mod 4), while the mobile ICBMs include the RS-12M1 Topol-M (SS-27 Mod 1) and RS-24 Yars (SS-27 Mod 2). The Topol (SS-25) has been withdrawn from service.

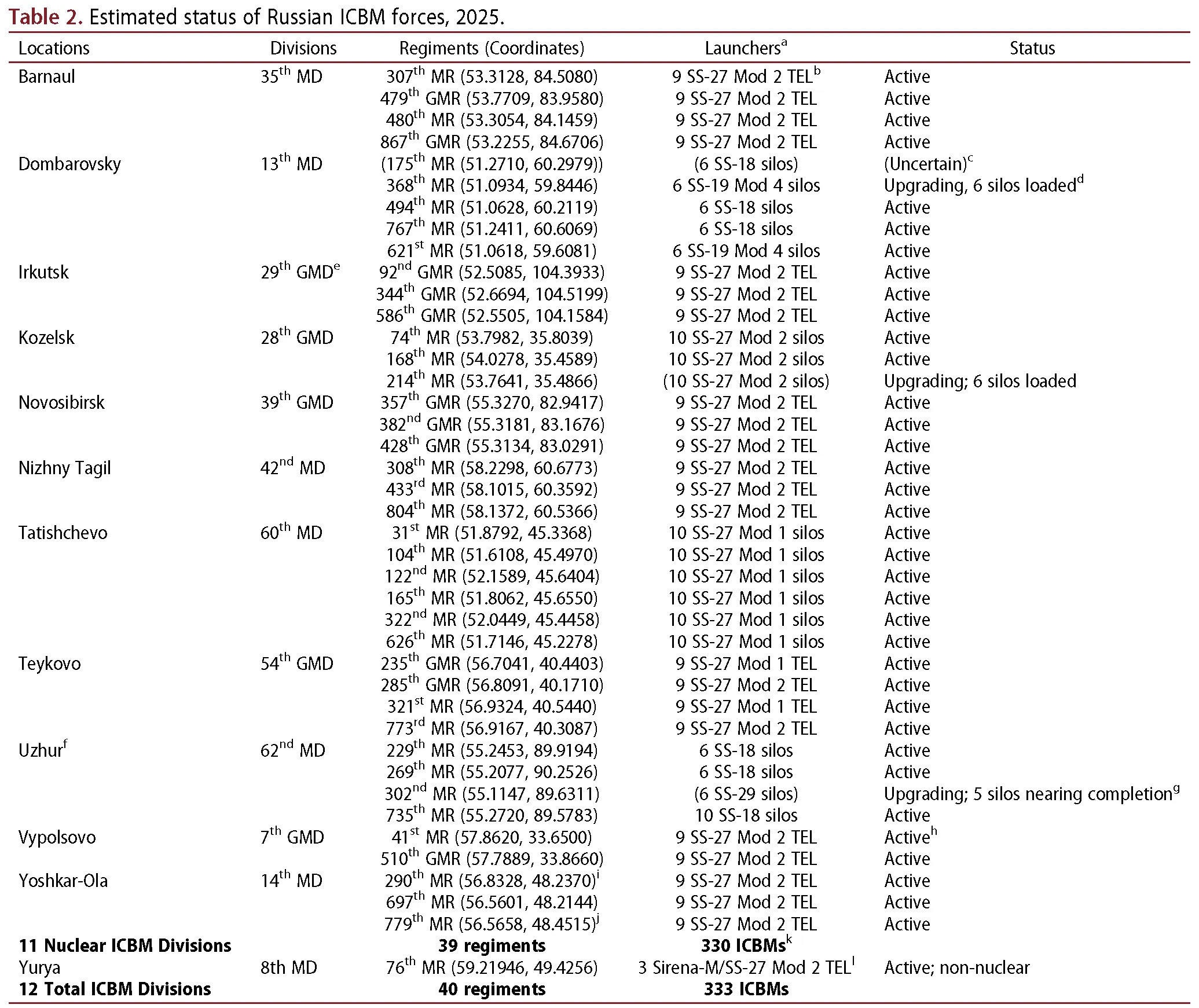

Cross-referencing our observation of satellite images with information from Russia’s official statements and New START’s previous data exchanges, we estimate that Russia may have approximately 330 nuclear-armed ICBMs, which we estimate can carry up to 1,254 warheads (see Table 1). Modernization of the ICBM force also involves equipping upgraded silos with new air- and perimeter-defense systems, and the new Peresvet laser has been deployed with at least five road-mobile ICBM divisions for the purpose of “covering up their maneuvering operations” (Hendrickx 2020; Russian Federation Defence Ministry 2019), possibly implying that one role of Peresvet is to blind spy satellites.

Russia’s ICBMs are organized under the Strategic Rocket Forces in three missile armies with a total of 12 divisions consisting of approximately 40 missile regiments (see Table 2). One regiment in the 8th missile division at Yurya operates the Sirena-M—a system based on the SS-27 Mod 2 ICBM—which is believed to serve as a backup launch code transmitter and, therefore, is not nuclear armed. The Sirena-M has recently replaced the older Sirena command module.

The Russian ICBM force has been reduced in size for three decades, and Russia claims to be 88 percent of the way through a modernization program to replace all Soviet-era missiles with newer types on a less than one-for-one basis (Krasnaya Zvezda 2024). This publicly stated modernization rate has been unchanged since 2023, suggesting that ICBM modernization has slowed potentially as a result of prioritizing industrial capacity to support Russia’s ongoing war in Ukraine (Krasnaya Zvezda 2023).

To accommodate its ICBM modernization program, Russia appears to be expanding its solid-propellant motor production facilities (Hinz 2024). After the mobile RS-12M Topol (SS-25) ICBM was removed from active service in 2023, we assess that the last remaining active Soviet-era ICBM in the Russian arsenal is the silo-based SS-18. (Some legacy SS-19s have been reconfigured to carry the Avangard hypersonic glide vehicle.)

Unlike silo-based ICBMs, all of Russia’s mobile ICBM divisions have completed their upgrade from Soviet-era missiles. However, not all the upgraded garrisons have been expanded to accommodate all the vehicles required to support the new launchers. As a result, some support vehicles must be stored in the open under camouflage nets until the garrisons can host them. While several garrisons have completed conversion and expanded significantly in size, satellite images indicate that construction of others appears to have slowed or even stalled in recent years, forcing entire brigades to be temporarily stored on temporary concrete tarmacs.

Apart from the missiles and silos themselves, the upgrade of Russian ICBM forces also involves extensive modification of external security fences, internal roads, and support facilities. Each silo complex is also receiving a new “Dym-2” perimeter defense system, including automated grenade launchers, small arms fire, and remote-controlled machine gun installations (Krasnaya Zvezda 2021; Russia Insight 2018). Likewise, the Launch Control Centers that control each missile regiment are also receiving significant upgrades.

The RS-20V Voevoda (SS-18 Mod 5) is a silo-based, heavy ICBM first deployed in 1988. In 2022, Russian state media showed a video of the RS-20V bus indicating that it could carry up to 14 multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs) in two tiers of seven warheads (Kornev 2022); however, the Russian Ministry of Defence’s website indicates that the RS-20V Voevoda would carry up to 10 warheads—the number that Russia declared for the missile under the START treaty (Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation n.d.). It is believed that the remaining four bus slots would be used to carry decoys.

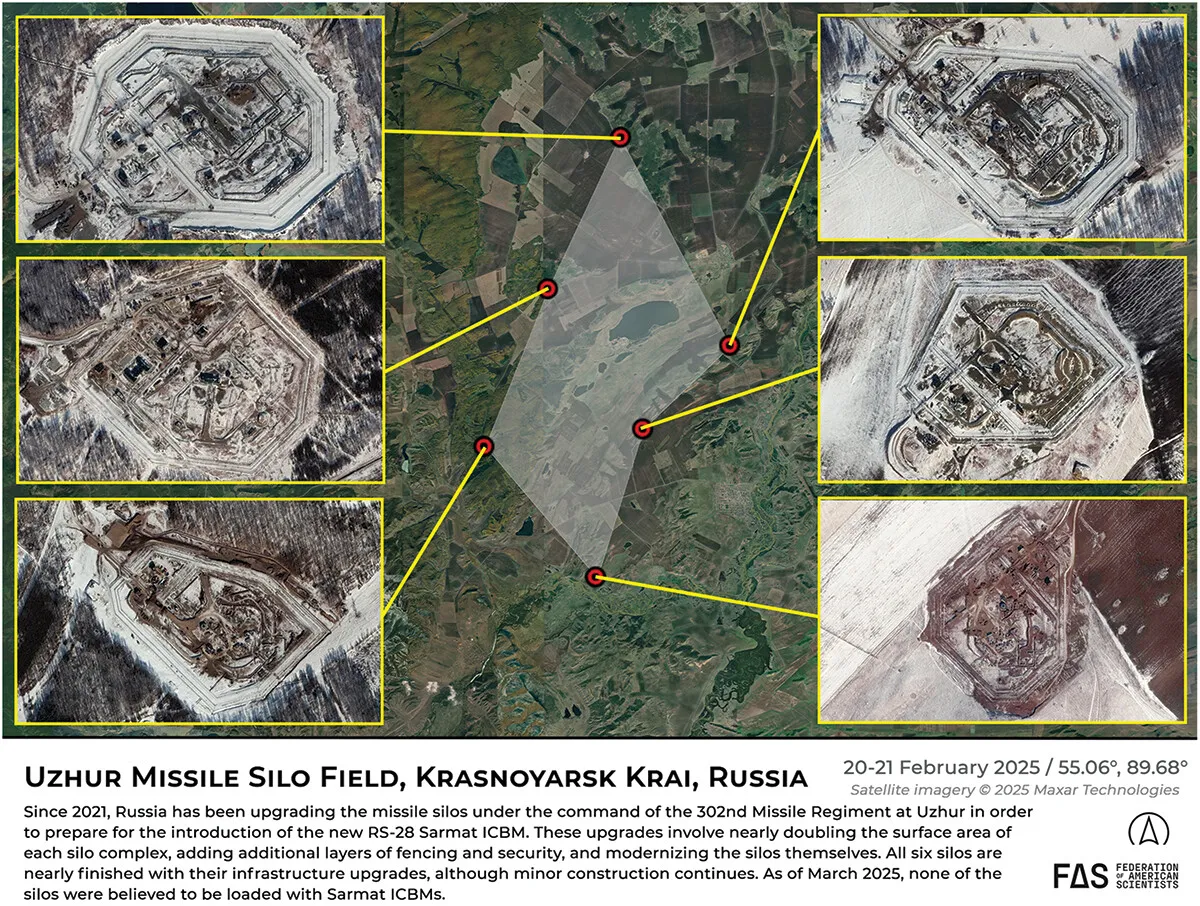

The RS-20 Voevoda is reaching the end of its service life, with approximately 34 SS-18 Mod 5s that can carry up to 340 warheads remaining in the 13th Missile Division at Dombarovsky and the 62nd Missile Division at Uzhur. We estimate that the number of warheads on each RS-20V has been reduced to meet the New START limit for deployed strategic warheads. The RS-20V formally began retiring in 2021 to prepare for the introduction of the RS-28 Sarmat (SS-29) ICBM at the Uzhur missile field, beginning with the 302nd Missile Regiment.

The silo-based, six-warhead UR-100N UTTKh (SS-19) ICBM, which entered service in 1980, was previously retired from combat duty but a small number of them have been converted and are being deployed with two regiments of the 13th Missile Division at Dombarovsky as the SS-19 Mod 4 with the new Avangard hypersonic glide vehicle. The first regiment—the 621st—completed its rearmament in December 2021 (Russian Federation 2021), and the second regiment—the 368th—reportedly completed its rearmament in December 2023 (Krasnaya Zvezda 2023). However, regiment-related construction—including the laying of new cable lines—was still ongoing as of late 2024, and the regiment may not have reached full operational capability yet. The UR-100N UTTKh ICBM continues to be life-extended and is eventually expected to be replaced by the SS-29 Sarmat (TASS 2025a).

The RS-12M1 and RS-12M2 Topol-M (both of which are known by the NATO designation SS-27 Mod 1) are single-warhead ICBMs that come in either mobile (M1) or silo-based (M2) variants. Deployment of the SS-27 Mod 1 was completed in 2012 with a total of 78 missiles: 60 silo-based missiles with the 60th Missile Division in Tatishchevo, and 18 road-mobile missiles with the 54th Guards Missile Division at Teykovo. In December 2024, Commander of Russia’s Strategic Rocket Forces Col. Gen. Sergei Karakaev stated that his priority for 2025 will be the commencement of the rearmament for one mobile regiment (at Teykovo) and one silo regiment (at Tatishchevo) with RS-24 Yars (SS-27 Mod 2) ICBMs (Krasnaya Zvezda 2024). The remaining Topol-M regiments will be upgraded to RS-24 Yars throughout the second half of the decade. However, judging from the time it has taken to upgrade other ICBM divisions, completion of Teykovo and Tatishchevo might take longer. Satellite imagery from June 2024 indicates the presence of ICBM loading vehicles at least one silo at Tatishchevo, potentially for the purpose of removing the Topol-M from its silo in preparation for the regiment’s rearmament (Figure 1). The eventual replacement of single-warhead Topol-M with Yars equipped with MIRVs could potentially add several hundred warheads to Russia’s ICBM force.

The RS-24 Yars (SS-27 Mod 2) is a modified SS-27 Mod 1 that can carry up to four MIRVs. It appears that there are currently several variants of the Yars system: One is reportedly equipped with “light warheads” and another (known as Yars-S) is reportedly equipped with more powerful, medium-yield warheads for use against hardened targets (Kornev and Ramm 2021). As of March 2025, Russia was still in the midst of upgrading the final regiment of the 28th Guards Missile Division at Kozelsk to the RS-24 Yars, and appears to be loading only about two ICBMs per year. In 2024, silo loadings at Kozelsk took place in November and December (Krasnaya Zvezda 2024, Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation 2024a). In December 2024, Col. Gen. Karakaev claimed that Russia would complete the regiment’s rearmament in 2025. However, this deadline may not be reached: Two silos had not yet begun construction as of March 2025 and minor construction appeared to still be ongoing at some of the other silos.

During an interview with the Russian Ministry of Defence’s TV channel in December 2020, Karakaev declared that approximately 150 mobile and silo-based Yars had been deployed by the Strategic Rocket Force (Zvezda 2020). We estimate that, as of March 2025, this number had grown to approximately 206 mobile and silo-based Yars missiles.

The next major phase of Russia’s ICBM modernization will be the long-awaited replacement of the RS-20V Voevoda (SS-18) with the new RS-28 Sarmat (SS-29). Eventually, the Sarmat will also replace the SS-19 Mod 4. The introduction of Sarmat—initially scheduled for 2018—has been marked by years of manufacturing and technical delays, as well as numerous testing failures. The delays have created political pressure on the defense establishment resulting in confusing and conflicting statements on the part of various Russian high-level officials about progress that contrast with observations on the ground through satellite imagery.

Except for Sarmat’s first flight test in April 2022—its only known successful flight test—the missile’s test record has been abysmal. According to US officials, a test in February 2023 likely ended in failure, and several others were canceled or postponed (Interfax 2022d; Kamchatka Info 2022; Liebermann and Bertrand 2023; TASS 2021b). In September 2024, a Sarmat flight test suffered another catastrophic failure, which significantly damaged its test silo at the Plesetsk Cosmodrome (Trevelyan 2024).

Despite insufficient numbers of successful tests, Russian officials have repeatedly claimed that the Sarmat is close to deployment. In November 2022, the General Director of the Makeyev Rocket Design Bureau—responsible for the design of Sarmat—claimed that the missile had already entered serial production (Emelyanenkov 2022). Moreover, in October 2023, the Russian Ministry of Defence noted on the Telegram messaging app that the “final stages” of construction and installation were underway at the first launch facilities and associated command post (Russian Federation Defence Ministry 2023). In November 2023, TASS—apparently incorrectly—reported that the first Sarmat regiment was already on “experimental combat duty” and that it would officially enter combat duty in December 2023 (TASS 2023e). In December 2023, Karakaev noted that work on the Sarmat had been “practically completed” (Krasnaya Zvezda 2023).

As of March 2025, satellite imagery indicated that the 302nd Missile Regiment at Uzhur had been disarmed to accommodate for Sarmat-related upgrades to the regiment’s silos and launch control center, and that all six of the regiment’s silos were at advanced stages of construction (see Figure 2). Construction may have been completed at some of these silos, although we assess that, as of March 2025, no Sarmat missiles had been loaded and placed on combat duty yet. Notably, the Sarmat upgrade was not mentioned during an annual end-of-year interview with Karakaev in December 2024, suggesting that no significant milestones had been achieved in 2024 that could be announced (Krasnaya Zvezda 2024).

If the Sarmat replaces all current SS-18s, it will be installed in at least up to 46 silos of the three regiments at the Dombarovsky missile field and four regiments at the Uzhur missile field (six regiments of six missiles and one regiment of 10 missiles).

Some media sources have dubbed the Sarmat missile the “Son of Satan” because it is a follow-on to the SS-18, which the United States and NATO designated “Satan”—presumably to reflect its extraordinary destructive capability. The operational configuration will likely be close to the payload on the SS-18 (up to 10 warheads) plus penetration aids. A small number of Sarmat ICBMs could probably be equipped to carry Avangard hypersonic glide vehicles, which are currently being installed on a limited number of SS-19 Mod 4 boosters at Dombarovsky. In December 2024, Karakaev noted that the Avangard command posts were named “Bugai” (Bull) (Krasnaya Zvezda 2024).

Sarmat is believed to have a significantly longer range than other Russian ICBMs. Col. Gen. Karakaev has stated that Sarmat can travel over both the North and South Poles (Lenta 2023), and in 2023 a Russian company involved with testing the Sarmat issued an environmental study indicating that Russia could plan to test the missile to a range of nearly 15,000 kilometers (2023a). The very long range may be more important for public relations than operational necessity, so to test the Sarmat and other ICBMs at shorter operational ranges, Russia is building a new testing ground at Severo-Yeniseysky—a decision announced in December 2020 (2023b; Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation 2020). Major construction at the test site may have been completed by the end of 2024, although it does not appear to have been used yet. It is possible that this new testing complex was also motivated by the fact that Kazakhstan—where Russia has historically test-flown its missiles into the Sary-Shagan site—is a state party to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which requires “the elimination or irreversible conversion of all nuclear-weapons-related facilities” (United Nations 2017).

Russia also appears to be in the early stages of development on at least two new ICBM programs, as well as on various hypersonic glide vehicles that could be fitted atop modified ICBMs. There is significant uncertainty, however, regarding the various designations and capabilities of these systems. In December 2021, Karakaev stated that “a new mobile ground-based missile system” is being developed and, in December 2022, noted that the system would have “greater mobility” than Yars and would officially begin development in 2023 (Krasnaya Zvezda 2021, 2022). In December 2023, Karakaev indicated that this system would have an emphasis on stealth and could eventually replace the RS-24 Yars in the longer term (Krasnaya Zvezda 2023). However, no mention of these systems was made in Karakaev’s December 2024 remarks.

It is unclear which missile system Karakaev referred to in his annual remarks as there are several possible candidates. Russia is reportedly developing a new “Yars-M” ICBM that features multiple warheads with individual propulsion systems, known as independent post-boost vehicles (Kornev 2023a, 2023b; Kornev and Ramm 2021). (In this configuration, warhead separation would take place at an earlier stage in flight, thereby theoretically allowing for greater survivability against missile defenses.) Although the Yars-M will reportedly share a launcher and first stage with the Yars and Yars-S, the Yars-M missile complex represents a relatively novel delivery system, has a much higher GRAU index number than both the Yars and Yars-S missile complexes, and will likely still take years to develop (Kornev 2023a, 2023b). (The GRAU index is a naming system used by the Russian Ministry of Defence to catalog different weapons, equipment, and ammunition. The last numbers of each GRAU index indicate the specific model of the system; therefore, GRAU indices that are far apart from one another could indicate that they were developed independently from one another, rather than in tandem or right after each other.) The Yars-M fits a similar—and somewhat confusing—naming pattern for Russian ICBMs, in which certain ICBMs are given similar names (Yars and Yars-M, or Topol and Topol-M) despite not sharing very many technological similarities. It is believed that Russia has already tested the Yars-M.

The second ICBM in development is called “Osina-RV,” which can be launched from both mobile and silo launchers and is reportedly intended to be a modernized version of the Yars-M system (M51.4ever 2023c; Ryabkov 2023; War Bolts Военно-болтовой 2021). Flight tests of the Osina-RV were supposed to take place throughout 2021 and 2022; however, it is unclear whether they took place (M51.4ever 2023c).

Russia is also developing another ICBM system, called “Kedr,” to begin replacing the currently deployed Yars ICBMs in both mobile and silo configurations by 2030 (TASS 2021a). Kedr is the only Russian new ICBM system known to have been publicly acknowledged by the Commander of US Strategic Command since 2022 (Richard 2022).

Russia appears to also be developing a series of hypersonic glide vehicles for deployment atop its newer ICBMs, similar to how the Avangard hypersonic glide vehicle is currently deployed with the legacy SS-19 Mod 4 ICBM. Although public Russian industry documents have revealed some of their names—including Gradient-RV and Anchar-RV—as of the end of 2024, the programs remained highly secretive and their respective capabilities unclear. None of these programs, nor the new developmental ICBM programs, were mentioned by Karakaev in his end-of-2024 remarks.

In addition to ballistic missiles, Russia is also developing a nuclear-powered, ground-launched, nuclear-armed cruise missile with intercontinental range, known as 9M730 Burevestnik (NATO’s designation is SSC-X-9 Skyfall). However, this missile has faced serious setbacks, including nearly a dozen failed tests—one of which resulted in the missile being lost at sea and necessitating a recovery effort that catastrophically failed, killing five scientists and two soldiers at Nenoksa (DiNanno 2019; Panda 2019). Following an October 2023 New York Times analysis of satellite imagery that indicated a test of the Burevestnik could be imminent, Putin subsequently claimed that a successful test of the system had been carried out, although he did not provide any further details (Mellen 2023; RIA Novosti 2023b).

In 2024, a potential deployment site for the Burevestnik was identified by Decker Eveleth of the CNA Corporation to be located immediately next to a known nuclear storage site (Landay 2024). The deployment site, next to the Vologda-20 national-level storage site near Cherepovets some 360 kilometers (230 miles) north of Moscow, features nine launch pads in three groups inside explosive berms, with roads connecting the site to support buildings and the nearby nuclear bunkers. This would be a highly unusual deployment site, given that Russia does not typically place its missile launchers right next to nuclear warhead storage sites. Satellite imagery indicates that construction at the site began in 2021 and many features had likely been completed by the end of 2024, although many support buildings were still under construction. It is unlikely that any system had been deployed there by then.

Submarines and submarine-launched ballistic missiles

The Russian Navy operates 12 nuclear-powered, nuclear-armed ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) of two classes: five Delta IV-class SSBNs (Project 667BRDM Delfin) and seven Borei-class (Borey) SSBNs (Project 955/A), four of which are improved Borei-A (Project 955A) submarines. Each submarine can carry 16 submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), and each SLBM can carry up to six MIRVs, for an estimated combined maximum loading of approximately 992 warheads on 12 submarines (Table 1). However, not all these submarines are fully operational, and the warhead loading on some of the missiles may have been reduced for Russia to stay below the New START treaty limit on deployed warheads. One or two SSBNs are normally undergoing maintenance, repair, or reactor refueling at any given time and are not armed. As a result, the total number of warheads deployed on Russia’s SSBNs is possibly around 640.

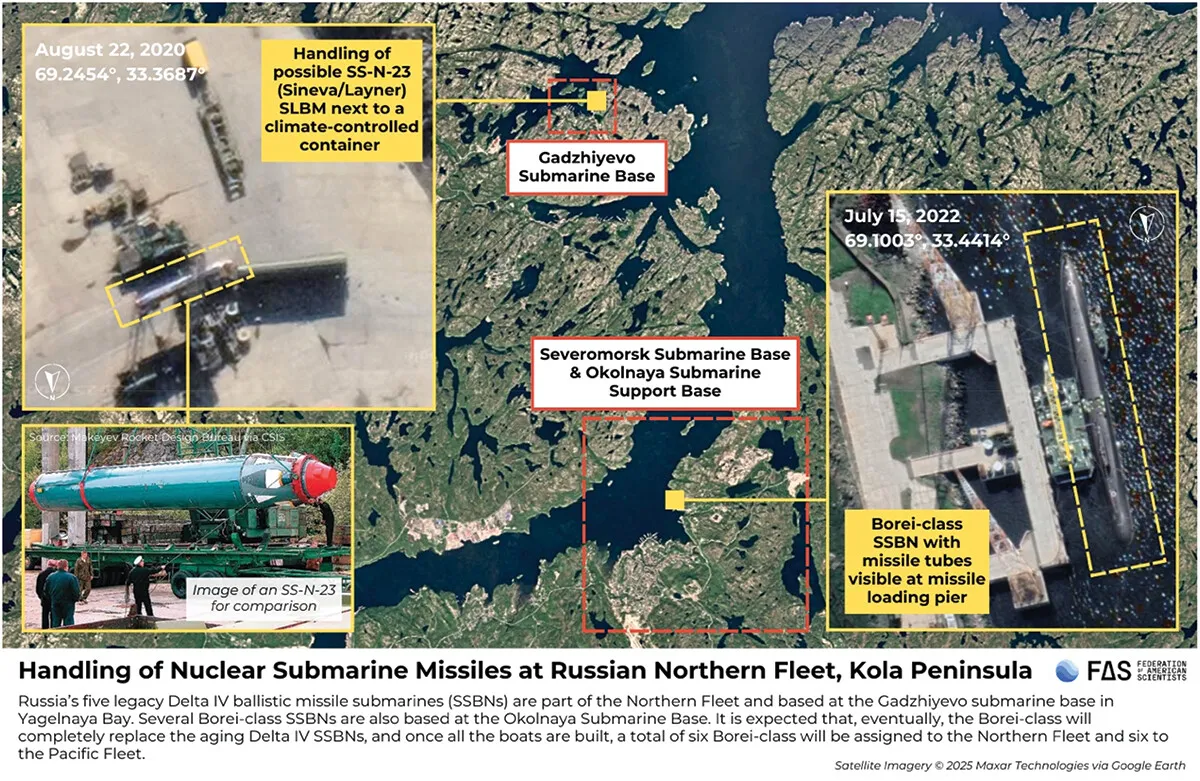

Russia’s five legacy Delta IV SSBNs—all of which were built between 1985 and 1992—are part of the Northern Fleet and based at Yagelnaya Bay (Gadzhiyevo) on the Kola Peninsula. The Delta IVs carry 16 of either the Sineva (SS-N-23) SLBMs, each of which carries up to four warheads, or the modified version, known as Layner (or Liner) (Podvig 2021). The Layner can be equipped with the same warhead as the Bulava SLBM and some believe could potentially carry up to 10 low-yield warheads but likely carries four (Podvig 2011). The SS-N-23 missiles and warheads are likely stored at the submarine bases (see Figure 3). Normally three or four of the five Delta IVs are operational at any given time, with the other one or two in various stages of maintenance. Russia previously possessed seven Delta IV SSBNs, but one of Russia’s submarines—Yekaterinburg (K-84)—was decommissioned in 2022 after 36 years of service and another—Podmoskovye (formerly K-64, now BS-64)—was deactivated in 1999 for conversion to a “special purpose” submarine (TASS 2016a, 2021c). In October 2024, one of the five active Delta IVs—the Novomoskovsk (K-407)—participated in Russia’s annual nuclear training exercise by firing a Sineva SLBM from the Barents Sea (Russian Federation 2024b).

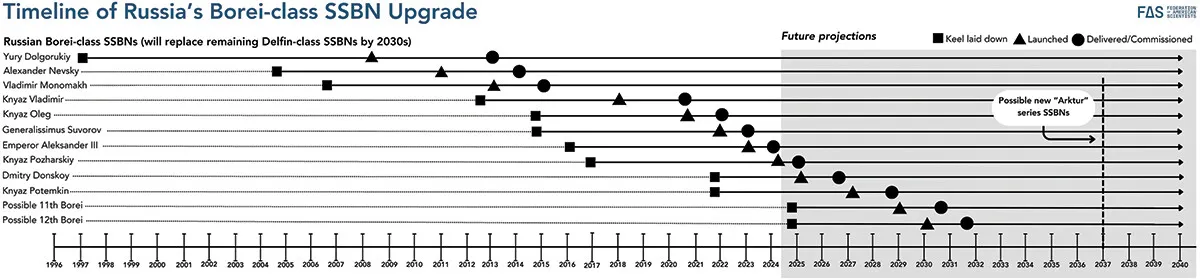

Each Borei (Project 955/A) SSBN is armed with 16 SS-N-32 (Bulava) SLBMs that can carry up to six warheads each. However, the missile’s payload may have been reduced to four warheads each to meet the New START limit on deployed strategic warheads. Seven Borei submarines are currently in service, with another five in various stages of construction, for a total of 12 planned Borei SSBNs. Six Borei SSBNs are expected to be assigned to the Northern Fleet (in the Arctic Ocean) and six will be assigned to the Pacific Fleet, replacing all remaining Delta IV SSBNs (TASS 2024a). The Knyaz Oleg (K-552) also participated in Russia’s annual nuclear training exercise in October 2024 by firing a Bulava SLBM into the Barents Sea (Russian Federation 2024b).

It has typically taken an average of seven years between each new Borei keel being laid down to the boat’s delivery to the Russian Navy, although some ships have been delayed (see Figure 4). The newest Borei-class SSBN—Emperor Alexander III—was launched in December 2022, began sea trials in mid-2023, and test-launched a Bulava SLBM from the White Sea in November 2023 before it was commissioned to the Navy’s Pacific Fleet in December 2023 (Russian Federation 2023; TASS 2021g, 2022b, 2023j). The next SSBN, Knyaz Pozharsky, was supposed to be commissioned at the end of 2024 but seems to have been delayed (TASS 2024b, 2024c). TASS reported that the keels for the final two Borei submarines were planned to be laid in 2024 but appear to have been delayed again (TASS 2024a). It is possible that two additional Borei SSBNs will be ordered.

A possible concept for the next generation of Russian strategic nuclear submarines—known as “Arktur” or “Arcturus”—was unveiled at the Army 2022 International Military-Technical Forum and would potentially start replacing the Borei-class after around 2037 (RIA Novosti 2023a). The Arktur-class design is expected to be smaller than the current Borei-class and will have a reduced number of missiles (RIA Novosti 2022). It could also potentially function as a carrier for an unmanned underwater vehicle, or autonomous uninhabited underwater vehicle (ANPA) “Surrogates,” suggesting an expanded role relative to traditional SSBNs (Dempsey 2022; RIA Novosti 2024). In an interview with Russian news agency RIA Novosti, Igor Vilnit, the General Director of the Rubin Central Design Bureau that designs Russia’s nuclear and diesel-electric submarines, said the fifth-generation “Arcturus” will focus on “robotics” and will be distinguished by “even higher stealth, as well as the ability to disorient enemy assets” (RIA Novosti 2024). At this stage, it is unclear what this future submarine class will eventually look like.

In addition to ballistic missiles, the Russian Navy is also developing a nuclear-powered, intercontinental-range, nuclear-armed torpedo called Poseidon. Underwater trials for the Poseidon began in December 2018. The weapon will be carried by specially configured submarines and is scheduled for delivery to the Navy in 2027 (TASS 2018c). The first of these special submarines—the Project 09852 Belgorod (K-329)—was launched in April 2019 and delivered to the Russian Navy in July 2022 (Naval News 2022; Sutton 2021). Russian defense sources indicated that the “first batch” of Poseidon torpedoes had been produced and would soon be delivered to the Belgorod submarine, despite an apparent aborted test of the torpedo in November 2022 (TASS 2023d). The aborted test reportedly was followed by a throw test of a Poseidon mock-up using the Belgorod in January 2023, and additional reports suggested that another test might have happened in June 2023 (Cook 2023b; Sciutto 2022; Sutton 2023; TASS 2023m).

Belgorod will be Russia’s largest submarine and reportedly will be capable of carrying up to six Poseidon torpedoes, each of which are rumored to have a large-yield warhead, allegedly in multi-megaton range (Hruby 2019; TASS 2019b). The submarine was seen operating in the Barents Sea throughout September 2022 (Sutton 2022), although it is unlikely that the Poseidon is already operational.

Subsequent Poseidon-capable submarines will be of a new class (Project 09851 Khabarovsk), the first of which was expected to be delivered in the autumn of 2021, but appears to have been delayed and may still be at the final stages of construction at the Sevmash shipyard (Starchak 2023a; TASS 2021i, 2023l). The Khabarovsk will reportedly also be capable of carrying up to six Poseidon torpedoes (TASS 2020h). One more submarine is planned to be delivered to the Russian Navy by 2027, for a total of at least three Poseidon-capable submarines (TASS 2023d).

The Pacific Fleet naval base at Kamchatka reportedly will be upgraded by 2025 to eventually homeport the Belgorod and Khabarovsk (TASS 2023a). Significant warhead storage upgrades are also underway at the base. In August 2024, Russian Presidential Aide Nikolai Patrushev referenced Sweden and Finland’s ascension to NATO as “aggravating the situation” in the Arctic and said that “increasing the combat readiness of the Northern Fleet, an important base of which is the Kola Bay,” is one of Russia’s priorities for securing its interests in the region (TASS 2024d).

Over the years, there have been occasional reports of Russian submarine deployments off US and Mediterranean coasts (Brugen 2023). British Defence Secretary Ben Wallace stated in April 2023 that the United Kingdom was also tracking Russian submarines “in the North Atlantic and in the Irish Sea and in the North Sea doing some strange routes that they normally wouldn’t do” (Cook 2023a).

Strategic bombers

Russia operates two types of nuclear-capable heavy bombers: the Tu-160 (known to NATO as “Blackjack”) and the Tu-95 MS (“Bear-H”). We estimate that there are roughly 67 bombers in the active inventory, of which perhaps only 58 are counted as deployed under New START. This number was determined by cross-referencing satellite imagery of various strategic bomber locations and maintenance facilities during 2023. However, this estimate carries significant uncertainty after unconfirmed, open-source reports suggest that Russia may have changed the Unique Identification (UID) numbers that were used to designate each strategic bomber under New START (Podvig 2023).

Both bomber types can carry the nuclear AS-15 Kent (Kh-55) air-launched cruise missile and upgraded versions are being equipped to carry the new AS-23B (Kh-102) nuclear cruise missile. Several versions of the Tu-95 are thought to have been fielded over the years: the legacy Tu-95MS6 and Tu-95MS16 versions and the modernized Tu-95MSM version. The 1991 START Treaty distinguished between the two legacy variants given their different missile capacities: The Tu-95MS6 can carry up to six missiles internally, and the TU-95MS16 can carry up to six missiles internally and up to 10 missiles on wing-mounted pylons for a total of 16 missiles. It is possible, but unconfirmed, that the MS16 version at some point lost the external hardpoints, effectively turning it into the MS6 variant. The hardpoints are being restored as part of the Tu-95MSM modernization program that is equipping legacy Tu-95s to carry eight AS-23B missiles externally for a maximum of 14 missiles per aircraft, including the six AS-15 missiles stored internally. The Tu-160s are also being modernized to carry up to 12 AS-23B internally. The AS-23Bs being added during bomber modernization might eventually replace the AS-15.

During a visit by North Korean leader Kim Jong-un to Russia’s Knevichi airfield in September 2023, Russia’s Long-Range Aviation Commander revealed a Tu-160 aircraft reportedly equipped with “novel” Kh-BD cruise missiles, which could be based upon the existing AS-23B. The Commander said the new missile has a range of over 6,500 kilometers—potentially indicating a nuclear role given that nuclear warheads weigh much less than heavy conventional munitions, therefore saving weight for fuel. Russia’s Defence Minister added that Tu-160s will be able to carry 12 missiles, though some experts are doubtful of this claim (Cook 2023c; TASS 2023c). No more information has emerged about this missile.

It is unknown how many nuclear weapons are assigned to the heavy bombers. Each Tu-160 aircraft can carry up to 40 metric tons of ordnance, including 12 air-launched cruise missiles, whereas the Tu-95 MS can carry six to 14 cruise missiles, depending on configuration. Combined, the bombers could potentially carry over 650 weapons, but we estimate that weapons only exist for deployed bombers for a total of approximately 580 bomber weapons (Table 1). Of these, we estimate that roughly 200 might be stored at Engels Air Base in Saratov oblast and Ukrainka Air Base in Amur Oblast; the rest are thought to be in central storage. Modernization of the nuclear weapons storage bunker at Engels Air Base continued throughout 2022.[2]

STRATCOM Commander General Cotton stated recently that both the Tu-95 and Tu-160 “are capable of carrying nuclear gravity bombs” (Cotton 2025, 5). But the old and slow Tu-95 bomber would not stand much of a chance against modern air defense systems, the Tu-160 is not a stealth bomber, and although both have been used to launch cruise missiles during the war in Ukraine, neither is believed to have carried out gravity bomb attacks. Consequently, we do not count gravity bombs for the heavy bombers. Some of Russia’s bombers have been damaged by Ukrainian retaliation attacks. After a likely Ukrainian airstrike on Engels Air Base in December 2022, Russian officials reported that two planes were damaged, one of which was a Tu-95 bomber as visible on satellite imagery (Kramer, Schwirtz, and Santora 2022; Kristensen, Korda, and Reynolds 2023; Röpcke 2022).

Russia carried out several heavy bomber exercises during 2024, including in October when some Tu-95 MS bombers participated in what the Kremlin called a “Strategic Deterrence Forces exercise,” during which the aircraft fired air-launched cruise missiles (Russian Federation 2024b).

Russia has historically housed all its strategic bombers at Engels Air Base and Ukrainka Air Base, but satellite imagery reveals that Russia began deploying some of its bombers to Belaya Air Base in Irkutsk oblast as early as October 2022 and to Olenya Air Base in Murmansk Oblast as early as August 2022. This is likely intended to reduce the number of bombers operating out of Engels Air Base, where they are now vulnerable to Ukrainian drone attacks. Confirming this assessment, the number of Tu-160 bombers deployed to Belaya Air Base increased after December 2022, and as of March 2025 Russia continues deploying a squadron of 8 Blackjacks from Belaya. Satellite imagery of Engels Air Base from March 2025 shows just two Tu-160 bombers present. Russia also appears to be operating approximately 11 Tu-95 Bears out of Olenya Air Base as of March 2025. These bombers are notably forward-deployed and less than 20 kilometers from the Olenegorsk-2 nuclear warhead storage facility.

The Russian Ministry of Defence was reportedly considering deploying a new Tu-160 regiment to Ukrainka Air Base for missions in the Far East region, but Blackjacks are normally not visible on satellite images of the base. On December 14, 2023, Tu-95 bombers conducted a joint strategic air patrol with Chinese H-6 bombers over the Sea of Japan and East China Sea—the second such exercise in the year 2023 (Mahadzir 2023). A small number of Tu-160s occasionally conduct Arctic and Far East patrol missions from Ugolny Airport near Anadyr. Most recently, two Blackjacks conducted an 11-hour Arctic patrol flight in January 25 according to the Russian Ministry of Defense (Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation 2025).

In addition to modernizing its existing strategic bombers, Russia is also reproducing additional Tu-160 bombers and appears to plan as many as 50 aircraft. There is considerable confusion about the designations of the various upgraded models: Tu-160M, Tu-160M1, and Tu-160M2. It appears that all upgraded Tu-160s fall under the Tu-160M designation with the M1 and M2 suffixes referring to successive modernization phases. The first phase reportedly includes a new engine—the NK-32-02—that is said to increase the aircraft’s range by approximately 1,000 kilometers (TASS 2017), as well as a new autopilot system and the removal of obsolete components, whereas the second phase includes a new radar, cockpit, communications, and avionics equipment (TASS 2020c, 2020f). Some Tu-160s are being reproduced, modernized with brand-new airframes.

The Tu-160M’s first flight with its olderengine was conducted in February 2020, and the aircraft’s first flight with its next-generation engine took place in November 2020. The Russian United Aircraft Corporation declined to show pictures of the November test flight due to classification concerns, instead electing to couple its announcement with pictures of an older version of the plane (United Aircraft Corporation 2020). The first newly manufactured Tu-160M bomber conducted its maiden flight in January 2022 (United Aircraft Corporation 2022). Russia’s state tech corporation, Rostec, announced in July 2023 that the aircraft had entered joint trials of the Ministry of Defence and the United Aircraft Corporation. In February 2024, President Putin visited the Gorbunov factory to inspect four Tu-160Ms and take an approximately 30-minute flight on one of the modernized bombers, the “Ilya Muromets” (Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation 2024b). In an interview after the flight, Putin stated that the modernized Tu-160s “can be accepted into the Armed Forces” (Associated Press 2024a). The Russian Air Force may have received its first modernized Blackjacks, though there has been no official confirmation of this. According to Russian media, the Ministry of Defense is expected to receive 10 Tu-160Ms by 2027 (Redstar 2018).

The delays associated with the Tu-160M program have been so severe that the Russian Ministry of Industry and Trade has filed a lawsuit against the aircraft manufacturer (Interfax 2022c). It is possible that the eventual target of 50 new Tu-160M bombers will not be reached, but if it does, it would probably result in the retirement of most, if not all, of the remaining Tu-95MSs, which are expected to be retired before 2035.

The Tu-160 modernization program, meanwhile, is only a temporary bridge to the next-generation bomber known as PAK DA, the development of which has been underway for several years. The subsonic aircraft will reportedly have a reduced radar signature and will be able to carry long-range cruise missiles and hypersonic missiles (Tsukanov 2023). The Russian government signed a contract with manufacturer Tupolev in 2013 to construct the PAK DA at the Kazan factory. Research and development work on the PAK DA has reportedly been completed, and the aircraft is expected to share many systems with the Tu-160 M (TASS 2019a). Construction of the first aircraft’s cockpit reportedly began in the spring of 2020, and final assembly has been postponed from 2021 to 2023 in advance of flight trials (TASS 2020c, 2021h). Rostec announced in December 2023 that specialists completed development of a testing facility and test benches for the PAK DA (TASS 2023h). State flight tests (which typically take place following flight tests by the aircraft’s manufacturer) of the PAK DA are scheduled for February 2026, with initial production expected to begin in 2027 and with serial production in 2028 or 2029 (Izvestia 2020; TASS 2019d). However, it is unclear whether the Russian aviation industry has enough capacity to develop and produce two strategic bombers at the same time, which suggests that this development schedule could face delays.

Nonstrategic nuclear weapons

Russia is modernizing many of its shorter-range, so-called “nonstrategic” dual-capable weapons and introducing new types. This effort is less clear and comprehensive than the strategic forces modernization plan but also involves phasing out Soviet-era weapons and replacing them with newer, but likely fewer, weapons. Although the number of non-strategic dual-capable launchers is increasing, that does not necessarily mean Russia is also increasing the number of nuclear warheads assigned to those launchers.

Although Trump administration officials in 2018 claimed that Russia had increased its nonstrategic nuclear weapons over the previous decade, the inventory in fact declined significantly—by about one-third—during that period (Kristensen 2019). The US Defense Intelligence Agency’s Worldwide Threat Assessment in 2021 and the State Department’s 2023 New START implementation report stated that Russia likely possesses “roughly 1,000 to 2,000 nonstrategic nuclear warheads”—the lowest number since the 1950s—and the State Department made the same estimate again in 2024 (US Defense Intelligence Agency 2021; US Department of State 2023a, 2025a). The range reflects different estimates within the US intelligence community, with the military typically using the higher number for its threat assessments. STRATCOM predicted in 2020 that “Russia’s overall nuclear stockpile is likely to grow significantly over the next decade—growth driven primarily by a projected increase in Russia’s non-strategic nuclear weapons” (Richard 2020, 5). And rumors resurfaced in early 2022 that some in the Intelligence Community believe the number of Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons could increase significantly—potentially doubling—by 2030 (Bender 2022; Kristensen 2022).[3]

Half of that decade later, the dramatic projected increase of Russia’s non-strategic nuclear weapons has not materialized. Without evidence to the contrary, we continue to estimate nearly 1,500 nonstrategic nuclear warheads, a significant decrease from a decade-and-a-half ago with nearly 2,000. These warheads are assigned for delivery by air, naval, ground, and various defensive forces. Although there are many rumors about greater inventories and additional nuclear systems, there is little authoritative public information available. This estimate—and the categories of Russian weapons that we have been describing in the Nuclear Notebook for years—accords with that of the 2024 State Department report to Congress, which states:

Russia has an estimated stockpile of 1,000–2,000 nonstrategic nuclear warheads, as of the latest unclassified assessment in 2023. This includes but is not limited to warheads for air-to-surface missiles, gravity bombs, depth charges, torpedoes, anti-aircraft, anti-ship, anti-submarine, anti-ballistic missile systems, and nuclear mines, as well as nuclear warheads for Russia’s dual-capable ground-launched missile systems. (US Department of State 2025a)

This assessment, however, raises questions about the US government’s assumptions and counting rules about Russia’s nonstrategic nuclear weapons. Most of these systems are dual-capable, which means not all platforms of a given type may be assigned nuclear missions and not all operations are nuclear. Moreover, even if Russia may increase a category of dual-capable launchers, it does not necessarily mean that the number of nuclear warheads assigned to that category also increases. Finally, many of the delivery platforms are in various stages of overhaul and would not be able to launch nuclear weapons at any given time.

Regardless of the uncertainty about the precise number, the Russian military continues to attribute a considerable role to nonstrategic nuclear weapons for use by naval, tactical air, and air- and missile-defense forces, as well as on short-range ballistic missiles. Part of the rationale for the Russian military to rely on nonstrategic nuclear weapons is that many of the potential targets for Russian nuclear strike plans are in Russia’s periphery; they do not require weapons of intercontinental range and but can be covered with shorter-range weapons. Moreover, Russia’s non-strategic nuclear weapons are intended to offset the superior conventional forces of NATO, particularly of the United States. After Russia’s significant conventional losses in the Ukraine war, the relative importance of non-strategic nuclear weapons will likely be further reinforced or even increase. Russia also appears to be motivated by a desire to counter China’s large and increasingly capable regional conventional forces. Finally, having a sizable inventory of nonstrategic nuclear weapons helps Moscow keep overall nuclear parity with the combined nuclear forces of the United States, the United Kingdom, and France; without the non-strategic nuclear forces, Russia’s nuclear stockpile would be significantly smaller (about a third of its size smaller).

During the summer of 2024, Russia conducted a non-strategic nuclear weapons exercise comprised of three phases: (1) readiness and preparation; (2) joint exercises with Belarus; and (3) combat use and deployment, which included trainings conducted by Iskander (SS-26) missile groups (Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation 2024c).

Sea-based nonstrategic nuclear weapons

As far as we can ascertain, the biggest user of nonstrategic nuclear weapons in the Russian military is the navy, which we estimate has roughly 704 warheads for use by land-attack cruise missiles, anti-ship cruise missiles, anti-submarine rockets, anti-aircraft missiles, torpedoes, and depth charges (Table 1). These weapons may be used by submarines, aircraft carriers, cruisers, destroyers, frigates, corvettes, and naval aircraft. The actual number of sea-based nonstrategic nuclear weapons may be lower than our estimate because not all vessels with dual-capable weapon systems may be assigned nuclear warheads.

Major naval modernization programs focus on the next class of nuclear attack submarines, known in Russia as Project 885/M or Yasen-M. The program has been subject to years of delay, partially due to technical deficiencies with the vessels themselves. Russia currently operates five Yasen submarines—Severodvinsk, Kazan, Novosibirsk, Krasnoyarsk, and Arkhangelsk—after the fifth boat was commissioned in December 2024 (TASS 2024e).

Four additional Yasen-M nuclear-powered nuclear-armed guided missile submarines (SSGNs)—named Perm, Ulyanovsk, Voronezh, and Vladivostok—are under various stages of construction. The next boat—Perm—which was laid down in 2016, has likely begun sea trials. Russian news agency TASS reported in 2023 that the Perm, which will be the first submarine to carry the nuclear-capable Tsirkon hypersonic cruise missile, will enter service with the Russian Navy in 2026 (TASS 2016b, 2023n). The remaining three boats were laid down in 2017, 2020, and 2020, respectively (TASS 2020g). Russia is reportedly considering building three additional Yasen-M SSGNs, although this has yet to be officially confirmed (Kornev 2023c; TASS 2023o).

The first Yasen submarine was reportedly 10 to 12 meters longer than the improved Yasen-M submarine and can therefore accommodate 40 Kalibr missiles-eight more than its successors (Gady 2018). The Yasen-M boats reportedly also have improved reactors and sonar systems, which may enhance their ability to evade detection (Kaushal et al. 2021). The Yasen submarines will replace Soviet-era attack submarines.

In addition to dual-capable Kalibr land-attack cruise missiles, the Yasen-class submarines will also be able to deliver the SS-N-26 Strobile (3 M–55 Oniks) anti-ship cruise missile, which the US Air Force’s National Air and Space Intelligence Center says is “nuclear possible,” and, beginning with the Perm, the SS-N-33 (3 M–22 Tsirkon) hypersonic cruise missile (Ramm and Stepovoy 2020). In 2021 and 2022, the Severodvinsk successfully test-launched the Tsirkon from surface and sub-surface positions—the first tests of the new system from a submarine (TASS 2021h, 2023g). According to Russian military officials, the Yasen-M submarines can salvo-launch several different types of missiles using modernized UKSK-M “universal launchers” that can accommodate multiple systems (Interfax 2021; Ramm, Surkov, and Dmitriev 2017; TASS 2021d).

Other upgrades of naval nonstrategic nuclear-capable platforms include those planned for the Sierra class (Project 945), the Oscar II class (Project 949A), and the Akula class (Project 971). While the conventional version of the Kalibr is being fielded on a wide range of submarines and ships, the nuclear version has probably replaced the SS-N-21 (Sampson) nuclear land-attack cruise missile on select attack submarines. An anonymous source from the Russian defense industry reportedly told TASS in 2019 that Russia might consider building a new type of cruise missile submarine based on the Borei SSBN design, which would be called Borei-K (TASS 2019c). However, there has been no confirmation of or updates on such a project; and given that the incoming Yasen-M submarines are also capable of delivering nuclear-armed cruise missiles, there may be no need for a new type of SSGN.

In addition to attack submarines, many surface ships and naval aircraft carry dual-capable weapon systems. The most important types are the 2,500 kilometer-range 3 M–14 Kalibr (SS-N-30A) land-attack cruise missile and the 3 M–55 Oniks (SS-N-26) anti-ship cruise missile, which are being added to many of Russia’s new surface ships and backfitted onto older ships, replacing older weapon types.

Air-based nonstrategic nuclear weapons

The Russian Air Force is estimated to be assigned roughly 334 nonstrategic weapons for delivery by Tu-22 M3 (Backfire) intermediate-range bombers, Su-24 M (Fencer-D) fighter-bombers, the Su-34 (Fullback) fighter bomber, the MiG-31K, as well as the new Su-57 aircraft that is now being added to the force. Other aircraft, such as the Su-30SM, might also be dual-capable, although this is unconfirmed.

The Tu-22 M3 can deliver Kh-22 (AS-4 Kitchen) air-launched cruise missiles, which are being replaced by an upgraded version known as Kh-32. The Tu-22 M3 is being upgraded to the new Tu-22M3M, which reportedly contains 80 percent entirely new avionics and shares a communications suite with the new Su-57 fighter and conducted its maiden flight in December 2018 (TASS 2020d; United Aircraft Corporation 2018). The second prototype of the upgraded Tu-22M3M conducted its first flight in March 2020, and has since conducted four additional flight tests-one of which tested the plane’s resilience at supersonic speeds (TASS 2020e). The Tu-22M3M—in addition to the Tu-160 M and future PAK DA strategic bombers—will eventually be equipped with a new Kh-95 hypersonic missile, a prototype of which has reportedly already been tested (RIA Novosti 2021).

Russia has carried out conventional attacks using Tu-22 M3 intermediate-range bombers during its war with Ukraine. After an ostensibly Ukrainian drone strike on Soltsy air base in August 2023 that destroyed a Tu-22 M3, Russia relocated the remaining Backfires at the base to Olenya air base on the Kola Peninsula, which is notably forward deployed and near NATO’s borders (Baker 2023; Nilsen 2023).

The Su-34 has played an extensive combat role in the war in Ukraine, resulting in heavy losses to the fleet. Because of these losses, the total number of operational Su-34 has remained relatively unchanged since pre-war numbers despite increased production. The International Institute for Strategic Studies’ 2025 Military Balance report estimates that Russia possesses approximately 124 Su-34 fighters (International Institute for Strategic Studies 2025). Russia purchased an additional 76 upgraded units of the Su-34 M with improved avionics and received several batches throughout 2023 and 2024, most recently in late December (Global Arms Trade Analysis Center 2023; Lavrov and Krezul 2020; TASS 2023b, 2023c; Rostec 2024). At a visit to the manufacturing plant in October 2023, Defense Minister Shoigu requested that production and repairs of the Su-34 be ramped up (TASS 2023b).

Russia has also developed a new long-range, dual-capable, air-launched ballistic missile system known as the 9-A-7760 Kinzhal “Dagger.” The missile, which bears similarities to the ground-launched SS-26 short-range ballistic missile used on the Iskander system, allegedly has a range of up to 2,000 kilometers if launched from a specially modified MiG-31K (Foxhound) designated as MiG-31IK, and up to 3,000 kilometers if launched from the Tu-22 M3 bomber (the range is the combined combat range of the aircraft plus the missile). According to Russian state media, the Tu-22M3M will be able to carry up to four Kinzhals (RIA Novosti 2018), although that remains to be seen. The MiG-31IK cannot carry both the Kinzhal and its regular air-to-air missiles and must therefore be deployed alongside a protective air detail (TASS 2018a). In December 2021, Russian Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu announced that in 2021 “a separate aviation regiment was formed, armed with MiG-31IK aircraft with the Dagger hypersonic missile” (Russian Federation 2021), apparently in the North Fleet area on the Kola Peninsula. Plans were reportedly underway to equip the Northern and Central Military Districts with Kinzhal missiles by 2024, and recently satellite imagery of MiG-31Ks at bases in the Kola Peninsula could suggest that the Kinzhal has been delivered to the region (Izvestia 2021; TASS 2021f). The Kinzhal has been used several times in the war in Ukraine (TASS 2022d). In February 2023, President Putin announced that Russia would speed up mass production of Kinzhal (TASS 2023i).

Additionally, the Russian Aerospace Force reportedly received its first batch of Su-57 (PAK FA) fighter jets in late 2020, and deliveries continued through 2023 and “considerably increased” throughout 2024 according to the CEO of the United Aircraft Corporation (TASS 2020a; United Aircraft Corporation 2022; TASS 2025b). The CEO also stated that the company would expand production capacity for the Su-57 during 2025, and that new batches will have new features and upgrades, including integration with unmanned aerial vehicles (TASS 2025b). The full contract is expected to comprise 76 planes for delivery by the end of 2028 for three regiments (Suciu 2021; TASS 2020b). The US Department of Defense says that the Su-57s are nuclear-capable (US Department of Defense 2018, 8). They will reportedly also be equipped with hypersonic “missiles with characteristics similar to that of the Kinzhal” (TASS 2018b).

Nonstrategic nuclear weapons in ballistic missile and air defense

The stockpile estimate of warheads for Russian missile and air defense interceptors is highly uncertain.

Since 2018, US agencies have stated repeatedly that Russia continues to possess nuclear warheads for defensive weapons. A 2023 State Department assessment suggested that Russia uses nonstrategic nuclear warheads for “anti-aircraft” and “anti-ballistic missile systems” (US Department of State, 2023b). Coastal defense systems using the 3 M–55 (SS-N-26) anti-ship missile might also be dual-capable.

This includes the A-135 anti-ballistic missile defense system around Moscow that is equipped with 68 nuclear-tipped 53T6 Gazelle interceptors. The system is being upgraded to the A-235 with the Nudol anti-ballistic and anti-satellite interceptor that is expected to enter service by the end of 2025 (TASS 2021e). It is possible that the A-235 system will not be equipped with nuclear warheads and will instead rely on conventional warheads or kinetic hit-to-kill technology (Krasnaya Zvezda 2017; Starchak 2023b).

Dual-capable air-defense systems include the mobile S-300 (SA-20) and S-400 (SA-21) that are designed for theater air (and some missile) defense. US government sources privately indicate that Russia maintains nuclear warheads for both systems. Not all air-defense units are thought to have a nuclear role, only select units tasked with defending high-value facilities. The S-300 and S-400 systems have been used extensively used in the war in Ukraine for both air-defense and offensive ground-strikes (TASS 2023f). It is possible, yet uncertain, that future and more advanced air-defense systems could eliminate the need for such a nuclear capability (Hendrickx 2021; TASS 2021e).

Given these developments, we estimate that nearly 250 nuclear warheads are available for air defense forces today, plus an estimated 95 additional warheads for the Moscow A-135 missile defense system and coastal defense units, making a total inventory of about 345 warheads (Table 1). However, it must be emphasized that this estimate, because of limited transparency and authoritative sources, comes with considerable uncertainty and low confidence about its accuracy.

Ground-based nonstrategic nuclear weapons

Ground-based systems with dual-capability include the 9K720 Iskander (SS-26) short-range ballistic missile and the 9M729 (SSC-8) ground-launched cruise missiles. It is possible, but unconfirmed, that the 9M728 (SSC-7) short-range ground-launched cruise missile also is dual-capable.