How to keep South Korea from going nuclear

By Duyeon Kim | March 1, 2020

How to keep South Korea from going nuclear

By Duyeon Kim | March 1, 2020

In 2016, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists published an analysis on whether South Korea would acquire its own nuclear weapons and concluded that such a development was unlikely, despite global media headlines that carried pro-nuclear South Korean voices.[1] There have, however, been significant strategic and political developments since then. The nuclear threat from North Korea has grown substantially, and more questions have been raised about the reliability of US security assurances to its key Asian ally. These developments have renewed a debate in South Korea—still in its early stage and confined largely to a small community of conservative national security experts and commentators—on whether Seoul should reconsider its nuclear options for the future.

Since 2016, North Korea has: tested its sixth nuclear device, claiming it was a thermonuclear bomb; fired several long-range ballistic missiles capable of reaching the United States; demonstrated advances in solid-fuel missile engines; and launched a barrage of short- and medium-range ballistic missiles that can strike South Korea and Japan. But in June 2018, hopes were raised across the South Korean public that Pyongyang might one day abandon its nuclear program, when a historic summit process began between US President Donald Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un. Now, however, a stalemate in nuclear talks and a December speech[2] in which North Korean leader Kim Jong Un announced his plans to further advance nuclear weapons developments have increased concerns in the South that North Korea will remain a nuclear-armed state permanently.

To better understand the current debate, I conducted extensive interviews and held in-depth conversations in the second half of 2019 and January 2020 with a wide range of prominent South Korean leaders who support and oppose nuclear weapons, across the country’s political spectrum: policymakers, editorial writers and working journalists, experts from research and academic institutions, serving and retired military officers and commanders, incumbent and former senior diplomats, and National Assembly advisors. Those interviews, many of which were conducted on a not-for-attribution basis to encourage candor, largely constitute the basis of this assessment of the current South Korean nuclear debate.

Recent questions about the credibility of the US extended deterrent are driven largely by what South Koreans see as a Trump leadership style that reflects his disdain for allies, including his transactional approach to alliances generally and his unilateral decision-making on key security matters that should involve consultation with allies. At the same time, many South Koreans worry that Trump’s behavior might actually reflect something deeper—a movement within the American public to reduce the United States overall commitments abroad.

Since 2016, South Korean public discourse on the possibility that the country might acquire its own nuclear weapons has also notably developed to extend beyond the usual pro-nuclear suspects of a few conservative commentators, politicians, and editorial writers. For example, former Foreign Minister Song Min-soon warned at the JoongAng Ilbo-CSIS Forum[3] in September 2019 that more South Koreans will inevitably want to take their country’s “own measures to create nuclear balance [with North Korea]” because of Trump, the US failure over decades to roll back North Korea’s nuclear program, and a deepening confrontation between the United States and China.[4] Many media reports and observers misinterpreted Song’s comments as support for South Korea’s nuclear weaponization, which they carefully were not. Eyebrows were nevertheless raised, because a prominent diplomat—who negotiated the September 2005 Six Party Joint Statement and is regarded as progressive, yet pragmatic and strategic, openly raised the issue.

Another notable development also came in September 2019 when two editorial writers at the centrist JoongAng Ilbo newspaper each wrote a column arguing for the nuclear option and “nuclear balance.”[5] Until now, only South Korea’s conservative newspapers openly advocated for nuclear weapons, and JoongAng Ilbo, its editor-at-large, and the head of its editorial board were opposed to nuclear weapons in 2016.[6] The paper’s senior journalists say that they are now allowed to freely express diverse views publicly in columns and that there is a growing number of junior journalists who personally believe South Korea should acquire its own nuclear deterrent.[7]

These two developments appear to be examples that reflect an evolving society in which the decades-old taboo of openly discussing the nuclear option is steadily cracking. The very beginnings of a more widespread public debate in South Korea, no longer confined to a few fringe conservative voices, may be emerging.

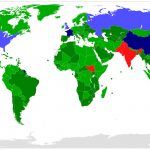

While many nuclear weapons advocates understand that a nuclear option for South Korea is not advisable in the foreseeable future, their interest and demands will exist and grow as long as North Korea possesses a nuclear weapons capability and South Koreans feel they cannot count on the US nuclear umbrella. The prospects of whether South Korean policymakers would seriously consider or even decide to acquire a nuclear arsenal would depend on the security situation, degree of public demand, and the political party in government. Any such decision in favor of a South Korean nuclear arsenal would have obvious implications for nuclear nonproliferation efforts generally and, specifically, for the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), which is under stress as it reaches 50 years of age this year.

An ideological divide

In South Korea, public opinion on a wide range of issues varies by the regions that citizens inhabit and the ideology they hold. When it comes to security and nuclear issues, however, South Korean views and beliefs are based on ideology rather than regional identity.

The ideological spectrum in South Korea is divided into three broad camps: the right (conservative), center, and left (progressive), but public opinion and discourse center around the right and left because they have ideologically fixed views and constitute the vast majority of the mass public. The center has traditionally been, and still is, far less visible and is viewed by South Koreans as those who change their views depending on the circumstance. As such, this article focuses on opinion from the left and the right sides of the spectrum. In general, conservative thinkers are anti-communism and place importance on security issues and the US-South Korea alliance, while their progressive counterparts prioritize inter-Korean relations and self-reliance over the alliance.

Depending on the issue, the ideological spectrum can be further divided into the far right, moderate right, moderate left, and far left.[8] South Koreans on the far right are the most loyal and supportive of the United States and the US-South Korean alliance. They see North Korea as their top enemy and threat to national security. Under normal circumstances, they believe Washington will defend South Korea against North Korea, but due to what they see as South Korean President Moon Jae-in’s uncertain relationship with Trump, they believe the solid support from Washington is collapsing.[9] Generally speaking, the far right supports South Korea’s nuclear weaponization and the return of US tactical nuclear weapons to the Korean Peninsula to strengthen national defenses and correct the asymmetry in military capabilities between the two Koreas.

Members of the moderate right agree that the US-South Korea alliance is critically and fundamentally important to national security and survival and are staunch supporters of it, but they also believe that the US cannot dictate to South Korea. They believe South Korea has advanced enough since the Korean War to deserve an equal partnership with the US rather than remain, indefinitely, as a “younger brother.” Moderately conservative thinkers also care about the credibility and reliability of US security guarantees in the face of a growing North Korean nuclear threat. This means that they are inclined to question US defense commitments during North Korean provocation cycles or when they perceive that Washington does not care enough to solve the North Korean nuclear problem. There is disagreement in this group, however, on whether Seoul should acquire its own nuclear weapons, whether US tactical nuclear weapons should be redeployed to Korea, and how Seoul should correct the military asymmetry. Moderate conservatives also believe that North Korea is their country’s top enemy.

Those who would be considered in the moderate left believe inter-Korean relations are the biggest priority, even above the US-South Korea alliance, although they recognize the importance of the alliance. They believe that if inter-Korean relations improve, then South Korea will be less dependent on the United States. However, many moderate progressives also believe that if the US disregards and undermines South Korea through actions and rhetoric, then they will have no choice but to cooperate more closely with China for their survival.[10] As one progressive scholar put it, moderately progressive thinkers see Trump as a blessing and a curse. He says they view Trump as a blessing because he met with and is committed to continue meeting Kim Jong Un, but they also regard Trump as a curse because of his demands for Seoul to pay an unrealistic amount to host US troops, his Indo-Pacific strategy, and his policies that make Seoul “stand against China.”[11] Moderate progressives are viewed by South Koreans as nationalists who eventually want their country to be self-reliant and autonomous from big, foreign powers. Moderate progressives are opposed to nuclear weapons.

Meanwhile, the far left—viewed by moderates and conservatives as being extreme nationalists—are what all thinkers outside this group describe to be “North Korea sympathizers.” As such, their ideology aligns with North Korea, they do not regard Pyongyang as a threat, and they say they see the US-South Korea alliance as a vice rather than a virtue.[12] They are opposed to both nuclear weapons and nuclear energy. Ultra-progressive thinkers question American motives and do not regard the credibility of Washington’s security guarantee as an issue. According to a prominent progressive scholar, the far left sees Trump as a blessing because he could terminate the US-South Korea alliance, which they believe will help improve inter-Korean relations.[13] He explained that the far left also believes that Seoul can ask the US military to leave South Korea if Trump demands too much money from Seoul to host troops and that phased denuclearization can occur simultaneously with the phased withdrawal of US troops.

Interest in nuclear weapons: determining factors

Recent interviews with experts across the ideological spectrum indicate that the degree of South Korean interest (among the public, politicians, media, and expert community) in nuclear weapons generally depends on five main factors: North Korea’s nuclear weapons capability; the status of nuclear diplomacy aimed at North Korea’s denuclearization; South Korean perceptions of US commitment to resolve the North Korean nuclear problem; the “Trump factor;” and South Korean perceptions of the credibility of the US extended deterrent. An ultimate policy decision on whether South Korea should pursue its own nuclear arsenal would fundamentally depend on whether a progressive or conservative government is in office because of their very different beliefs about nuclear weapons, North Korea, and the US-South Korea alliance.

North Korea’s nuclear weapons capability and nuclear diplomacy. At the core of South Korean interests in a nuclear arsenal is the existence of a North Korean nuclear weapons capability, which they believe creates an asymmetry between the Koreas’ military capabilities. As Pyongyang’s nuclear weapons programs and arsenal develop, South Koreans’ insecurity rises. Even if a nuclear agreement with Washington reduced the regime’s capability to the limited possession of fissile materials and a nuclear fuel cycle program, some South Koreans would still feel vulnerable and likely continue to call for their own nuclear capability. As South Korean insecurities rise, their interest in a nuclear arsenal also increases, especially if they do not see progress in denuclearization negotiations with Washington. Seeing a process of tangible denuclearization measures in North Korea in accordance with a nuclear agreement with Washington would temper South Korean voices for nuclear weapons during that time.

US commitment to resolve the threat. Ever since the first North Korean nuclear crisis in the early 1990s, frustration has grown among many South Korean conservatives and moderate progressives about the ambivalence of both Washington and Beijing to proactively and consistently deal with the North Korean threat. They saw three consecutive American presidents put the North Korea issue on the back burner because of more pressing American foreign policy priorities in the Middle East, only to have to tend to it after major North Korean provocations.[14]

Today, South Koreans across ideological divides are hopeful and relieved that an American president is dealing directly with Kim Jong Un and frequently talks about North Korea. However, conservatives and many moderate progressives criticize the lack of a real US strategy that supports the summit process, the refusal of Pyongyang to hold real working-level negotiations with Washington, and the absence of a real nuclear agreement.[15]

The “Trump factor.” South Koreans are concerned and frustrated over what they call the “Trump factor,” which has emerged as a new trigger, fueling national security concerns, resentment, and anti-American sentiment in South Korea (not to mention concern among security experts around the world). They point to Trump’s unilateral decision to halt major US-South Korean military exercises at his 2018 Singapore summit with Kim, his dismissal of Pyongyang’s short-range ballistic tests, which threaten South Korea (and Japan), his “insulting” demands for Seoul to pay exponentially more for combined defense costs, and his nonchalant comments about wanting to withdraw US troops from South Korea.[16] South Koreans see Trump’s military cost-sharing demands as disrespect for the value of the US-South Korea alliance, treating it as a money-making tool instead of an alliance forged on the basis of common values and national interests.[17]

These factors related to Trump are causing insecurities among South Korean conservatives and some moderate progressives and exacerbating suspicions about the reliability and credibility of the US extended deterrent (or, security guarantee).[18] As leading security expert Lee Sang-hyun at the Sejong Institute explains, “The way Korean people think [about a future scenario] is, Trump demands too much money [for troops] and we don’t give him what he wants, then maybe he will reduce US troops and then maybe we should consider our own nuclear weapons.”[19] On the other hand, the (progressive) head of a state-funded institute argues that “if the North Korean nuclear capability continues to grow and Trump reduces US troops, then progressives will [also] begin to question the reliability of the US extended deterrent and, in turn, accelerate peace with North Korea and ramp up its defense budget [instead].”[20]

Other experts warn that Trump could encourage or even inadvertently force South Korea to choose nuclear weapons. As veteran Korea specialist Ralph Cossa of the Pacific Forum points out, a South Korean “decision to go nuclear would be driven by lack of faith in the alliance or Trump pulling out troops or agreeing to end the UN Command/Combined Forces Command, so it’s a chicken and egg situation.”[21] Senior editorial writer Lee Mi-sook with the conservative daily Munhwa Ilbo says that South Korea cannot develop its own nuclear weapons without US permission because of technological and political reasons. But she also points out, “If, out of need, the US breaks the alliance and tries to retreat from Asia, it will be difficult for South Korea to deal with a nuclear North Korea. Then, just as divorcees provide alimony for example, shouldn’t the US allow South Korea to have its own nuclear weapons to defend itself?”[22]

The “Trump factor” is not a temporary phenomenon in the minds of some South Koreans. Former Foreign Minister Song Min-soon points out that “there is rising concern that even after a Trump presidency, the US extended deterrent will become less reliable or costlier over time, leading to more South Korean calls for nuclear balance between the two Koreas.”[23]

Reliability of the US nuclear umbrella. The “Trump factor” described above is exacerbating existing South Korean anxiety that the US nuclear umbrella can be lifted at any time. Such concerns existed well before Trump; South Koreans have long wondered whether the US would actually come to South Korea’s defense if the US homeland became vulnerable to North Korean nuclear weapons (known as the “de-coupling” of the US deterrent) or came under attack, as they have worried that Seoul will be powerless to cope with North Korea alone.[24] They also question whether Washington will actually use nuclear weapons to genuinely demonstrate its resolve—rather than using only conventional weapons (such as precision-guided munitions)—to preempt or retaliate against North Korea’s use of a nuclear weapon.[25] However, a former career senior diplomat said definitively that “no South Korean government [conservative or progressive] will permit the use of nuclear weapons on North Korea because South Korea will be affected environmentally.”[26]

At the same time, one veteran security expert at a state-funded research institute framed the reliability question differently. He explains that the question in South Koreans’ minds is, “What, as a sovereign state, should we do? It’s not about whether US reliability or credibility has gone up or down. Our security can’t be 100 percent dependent on the US extended deterrent, which existed even before North Korea developed nuclear weapons.”[27] For many South Koreans who share this view, there is no contradiction between having confidence in US security commitments and, at the same time, believing that their own country needs to find independent ways to protect itself from a threat just north of their border.

Ideology and political party in office. A serious policy consideration or decision to go nuclear will likely first depend fundamentally on the ideology of the South Korean president and his or her closest advisors. Progressive thinkers are generally opposed to both nuclear weapons and nuclear energy on the Korean Peninsula, which is a key motivation for the current Moon administration to phase out nuclear energy in the South. A leader of a (progressive) state-funded institute stated that “progressives don’t think nuclear weapons are necessary and they know it’s impossible for us to have nuclear weapons. Our defense spending is and has been the highest under most progressive governments.”[28]

At the same time, the chances that a conservative South Korean government will embark on the nuclear weapons route are also currently zero. Policy makers are aware of the serious consequences their country would face—harsh economic and political sanctions, the end of the US-South Korea alliance, the inability to sell nuclear power plants overseas, and the required withdrawal from key international agreements, including the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.

In the meantime, however, as long as there is no resolution to the North Korean nuclear issue, South Korean indigenous nuclear weapons supporters will continue to express their demands, which are motivated by five general objectives.[29] They seek more credible deterrence, so that South Korea can rely on the United States in a crisis. They want to correct what they see as a critical asymmetry between the two Koreas, so South Korea has leverage to negotiate with Pyongyang on mutual reductions in and eventual elimination of nuclear arsenals. Third, they aim to pressure Beijing and Washington to each exert enough pressure to “force” Pyongyang’s nuclear surrender. Also, some conservative politicians hope to score political points domestically by demonstrating resolve to “do something” in the face of a growing North Korean nuclear challenge. And finally, they are expressing widespread frustration and fear of abandonment, a sentiment felt by both conservatives and progressives in opinion polls, about Washington’s failure to rein in Pyongyang’s strategic weapons programs and the possibility that the US would not defend South Korea in a crisis.

The US extended deterrent: reliability/credibility vs. capability

My extensive interviews in recent months have found that the reliability issue is largely based on perception, rather than the actual capability of the United States to protect South Korea (although some military officers and security experts do point to ways the capability can be further strengthened).

Former Vice Foreign Minister Shin Kak-soo says the reliability and credibility of America’s security commitment have declined because of “Trump’s America first policy, his comments about withdrawing US troops, his unilateral halt of combined military drills, his disparaging comments about us, his handling of Syria by withdrawing US forces at the sacrifice of the Kurds, and neo-isolationism occurring in the US. These all show the US is not as credible as before.”[30] Trump’s apparent lack of concern about North Korea’s short-range ballistic missile (SRBM) tests particularly changed the perception of the South Korean mass public, elite, and opinion leaders. Former National Security Advisor Chun Yung-woo under a conservative president, who also served in senior positions during progressive administrations, said, “When we saw how Trump’s rhetoric translated into real policy by condoning SRBMs and going against UN Security Council resolutions [that ban flight tests], we started to doubt whether the US will really defend South Korean cities at the expense of the US homeland.”[31]

Many South Koreans also fear that a deeper trend—a focus inward— is occurring in both US public opinion and policy. Some say that the next US president will need to exert real effort to restore trust among the South Korean people. However, former Lieutenant General Shin Won-sik, former deputy commander of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, questioned whether trust can be restored after Trump, explaining that even from a strategic and practical standpoint, “the incentive is decreasing for the US to continue to be the global police, and it’s going toward an off-shore strategy, which is sufficient for deterrence. But the Korean public is worried about this shift away from on-shore strategy.”[32]

Other specialists point to a rising China. Leading nuclear expert Hwang Il-soon says “we feel more insecure with China’s ambitions in the region, and North Korea is bullying us on China’s shoulders. That’s why the Korean people can’t count on the US alone as we see a global trend moving away from nonproliferation with things like nuclear drones. With US-China rivalry unfolding, we are worrying about another Cold War arms race.”[33]

But some South Koreans also voice concerns about their own president, implying the absence of a leader who will prevent Trump from damaging the alliance and eventually abandoning them. A former career senior diplomat asserted that Moon “believes that if inter-Korean relations improve, then the [North Korean] threat reduces. He sees everything through the lens of inter-Korean relations and wants to improve it at all costs” and that “Moon sees the threat to South Korea as coming from the US.”[34] Several other conservative and progressive interviewees agreed.

Serving military officers and national security professionals express confidence in in terms of the actual capability of the US extended deterrent, but former generals like Kim Byoung-gi say that Trump’s unilateral halt of many combined military exercises is reducing readiness and weakening deterrence.[35] While these South Koreans also remain confident about the reliability of US security assurances, they believe it would be useful to do more to assure the South Korean public through visible demonstrations of US military capabilities on and near the Korean Peninsula.

Keeping South Korean interest in obtaining nuclear weapons low

South Korea’s continued nuclear abstinence will depend on two interrelated factors: North Korea’s actions, and the confidence of South Korean leaders and public in the effectiveness and credibility of the US security guarantee. The possibility of Seoul embarking on a nuclear weapons path will remain low if South Korean leaders and public see that Pyongyang’s nuclear weapons programs are being (or at least can be) reversed. For South Koreans to hold this view, US administrations will need to place North Korea at the top of their national security agenda.

Authorities in Washington will also need to take steps that reassure South Koreans that they can rely on the US extended deterrent. This can be done either by strengthening actual deterrence capability or by strengthening perceptions of deterrence with highly visible (yet symbolic) demonstrations, especially during North Korean provocation cycles.

South Koreans have suggested a range of measures to strengthen the reliability and credibility of the US extended deterrent. On the incremental end of the spectrum, those measures include the resumption of US-South Korean defensive military drills, publicized rotational deployments or temporary visits of US strategic assets (e.g., nuclear-capable submarines and aircraft, etc) and a greater South Korean voice in the planning of the US extended nuclear deterrent.

Moving toward greater enhancements to deterrence, South Koreans in the national security establishment have increasingly been calling for a NATO-style “nuclear sharing” mechanism with the US and a consultative platform like the NATO Nuclear Planning Group.

However, both concepts are widely misunderstood among most South Koreans, who inaccurately believe American allies are given access to US nuclear weapons in peacetime (“nuclear sharing”) and an equal voice or veto power over how and when American nuclear weapons might be used (“planning group”). Actually, there is no consensus yet within the South Korean government (even under a previous conservative administration) and among other leading politicians and defense specialists on what “nuclear sharing” ought to look like.[36]

Some South Korean defense specialists and former generals are fully aware that even if the NATO concept of “nuclear sharing”[37] were adopted for the US-Korea alliance, it would be only political and symbolic rather than a tool that provides practical military benefits. The American president, after all, has sole authority over his or her decision involving nuclear weapons.[38] South Koreans say the current progressive government would also oppose any “nuclear sharing” scenario, fearing Northeast Asia would become the site of a new arms race and provide Pyongyang with another reason or excuse to retain its nuclear weapons.[39]

Beyond nuclear sharing, there are other assurance measures voiced by concerned South Koreans that are more controversial even among the country’s national security professionals and are politically unrealistic in Washington. These steps, also symbolic rather than practical, include the redeployment of tactical US nuclear weapons to South Korea,[40] the tacit agreement for South Korea to possess a latent nuclear capability that includes storage of fissile material and a closed nuclear fuel cycle to supply it,[41] and even the deployment (or threat to deploy) new US ground-based ballistic missiles to Asia.[42]

Despite the existence of potential measures that would reassure South Korea about the US extended deterrent, the current strategic landscape poses challenges in keeping the South Korean interest in obtaining nuclear weapons low. For one, nuclear diplomacy is at a standstill, and North Korea is showing signs of further advancing its nuclear weapons capability. Second, the “Trump factor” is shaking South Koreans’ confidence in their ally’s pledge to defend them. Third, the issue of strengthening deterrence and assurance is a double-edged sword, particularly during a progressive South Korean administration. Steps aimed at reassuring America’s Asian allies by strengthening deterrence—either in terms of capability or perception—can send the wrong message to, or even provoke, North Korea and China, especially during times of diplomacy. Finally, many conservative and moderately progressive South Koreans believe their own president will reject any deterrence measures that will upset Pyongyang.[43]

Still, in efforts to strengthen assurance, Washington should find ways to accommodate South Korea’s interest in contributing its perspectives to operational planning for the US extended nuclear deterrent arrayed against North Korea. There is good reason for Washington to resist some South Korean requests for more information sharing and greater role in nuclear decision-making,[44] but US authorities should at least consider establishing a consultation channel through which the views of the South Korean president and commanding generals can be heard regarding various crisis or conflict scenarios, even though the US president will ultimately decide if and how nuclear weapons are ever used.

The NPT, although far from perfect, has been the bedrock of the international nonproliferation regime for half a century and succeeded in maintaining the number of states possessing nuclear weapons at a far lower level than originally predicted. South Korea has long been a champion of nonproliferation, and despite occasional headlines in global media, South Korean opposition to developing its own nuclear deterrent remains strong. But this opposition must not be taken for granted. Washington can prevent Seoul from crossing the nuclear threshold by keeping North Korea at the top of its foreign policy priorities and taking steps to assure South Koreans that America will always come to its defense.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Sources

[1] Robert Einhorn and Duyeon Kim, “Will South Korea Go Nuclear?” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, August 15, 2016. Available at: https://thebulletin.org/2016/08/will-south-korea-go-nuclear/

[2] See North Korean leader Kim Jong Un’s speech at the Workers’ Party Plenum as reported by his state media here: https://kcnawatch.org/newstream/1577829999-473709661/report-on-5th-plenary-meeting-of-7th-c-c-wpk/?t=1577839230030. For analysis of North Korea’s plans for 2020, see: https://thebulletin.org/2020/01/will-killing-of-irans-soleimani-influence-north-koreas-strategic-weapon-plans/

[3] “Navigating Geostrategic Flux in Asia: The United States and Korea,” JoongAng Ilbo-CSIS Forum 2019, Center for Strategic and International Studies, September 30, 2019, https://www.csis.org/events/joongang-ilbo-csis-forum-2019.

[4] Featured remarks by Song Min-soon, former ROK Foreign Affairs and Trade Minister, JoongAng Ilbo-CSIS Forum 2019, September 30, 2019.

[5] See http://mengnews.joins.com/view.aspx?aid=3067999 and http://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/news/article/article.aspx?aid=3068000&cloc=etc%7Cjad%7Cgooglenews.

[6] See: https://thebulletin.org/2016/08/will-south-korea-go-nuclear/.

[7] Author’s interview with JoongAng Ilbo senior journalist, January 2020.

[8] This article uses broad terms such as “progressive thinkers” or “conservative thinkers” unless their sub-factions are specified for contextual accuracy or deeper understanding. While there is some degree of diversity within each of them, the following categorization of the four groups still provides a basic understanding of each group’s thinking toward security, nuclear weapons, North Korea, and alliance issues.

[9] Author’s interview with a National Assembly advisor, January 2020.

[10] Author’s interview with a progressive scholar, January 2020.

[11] Author’s interview with a prominent progressive scholar, January 2020.

[12] Author’s conversation with a progressive individual, August 2019 and a progressive scholar, January 2020.

[13] Author’s interview of a prominent progressive scholar, January 2020.

[14] Robert Einhorn and Duyeon Kim, “Will South Korea Go Nuclear?” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, August 15, 2016.

[15] Author’s interviews, 2018- January 2020.

[16] Author’s interviews with conservative leaders, scholars, researchers, media, and general public, November-December 2019 and January 2020.

[17] Author’s interviews with conservative and progressive leaders, scholars, researchers, media, and general public, November-December 2019 and January 2020.

[18] Author’s interviews with conservative leaders, scholars, researchers, media, and general public, November-December 2019 and January 2020.

[19] Author’s interview of Dr Lee Sang-hyun, Senior Research Fellow, Sejong Institute, January 2020.

[20] Author’s interview, January 2020.

[21] Author’s interview of Ralph Cossa, President Emeritus, Pacific Forum, January 2020.

[22] Author’s interview of Lee Mi-sook, Senior Editorial Writer, Munhwa Ilbo, January 2020.

[23] Author’s interview with former Foreign Minister Song Min-soon, January 2020.

[24] Robert Einhorn and Duyeon Kim, “Will South Korea Go Nuclear?” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, August 15, 2016.

[25] Author’s interviews of conservative and moderate progressive leaders, scholars, researchers, media, and general public, November-December 2019 and January 2020.

[26] Author’s interview, January 2020.

[27] Author’s interview, January 2020.

[28] Author’s interview, January 2020.

[29] Robert Einhorn and Duyeon Kim, “Will South Korea Go Nuclear?” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, August 15, 2016.

[30] Author’s interview, January 2020.

[31] Author’s interview, January 2020. Off shore strategy means, strengthening air and naval capabilities.

[32] Author’s interview, January 2020.

[33] Author’s interview, January 2020.

[34] Author’s interviews, November 2019 and January 2020.

[35] Author’s interview, January 2020.

[36] Author’s interviews of and meetings with government officials at South Korea’s Defense Ministry, Foreign Ministry, and presidential office; politicians and their advisors; serving military officers and former generals; and defense specialists, 2016-January 2020.

[37] For example, pilots of US allies delivering US nuclear weapons.

[38] Author’s interviews, January 2020.

[39] Author’s interview of the head of a state-funded institute, January 2020.

[40] Cheon Seong-whun, “Redeploying American Tactical Nuclear Weapons to Counter North Korea’s Nuclear Monopoly,” The Asan Institute for Policy Studies, December 17, 2018.

[41] Advocated by former General Shin Won-sik, author’s interview, January 2020.

[42] Also called “INF missiles” after Washington pulled out of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty with Russia in August 2019. Author’s interviews of a security specialist and former government officials, January 2020.

[43] Author’s interviews of progressive and conservative experts, opinion leaders, and government officials, January 2020.

[44] Robert Einhorn and Duyeon Kim, “Will South Korea Go Nuclear?” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, August 15, 2016.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: North Korea, South Korea, South Korean nuclear weapons, nuclear arms, nuclear weapon

Topics: Nuclear Risk, Nuclear Weapons