The coronavirus pandemic: A people’s first draft of history

By Dan Drollette Jr | May 14, 2020

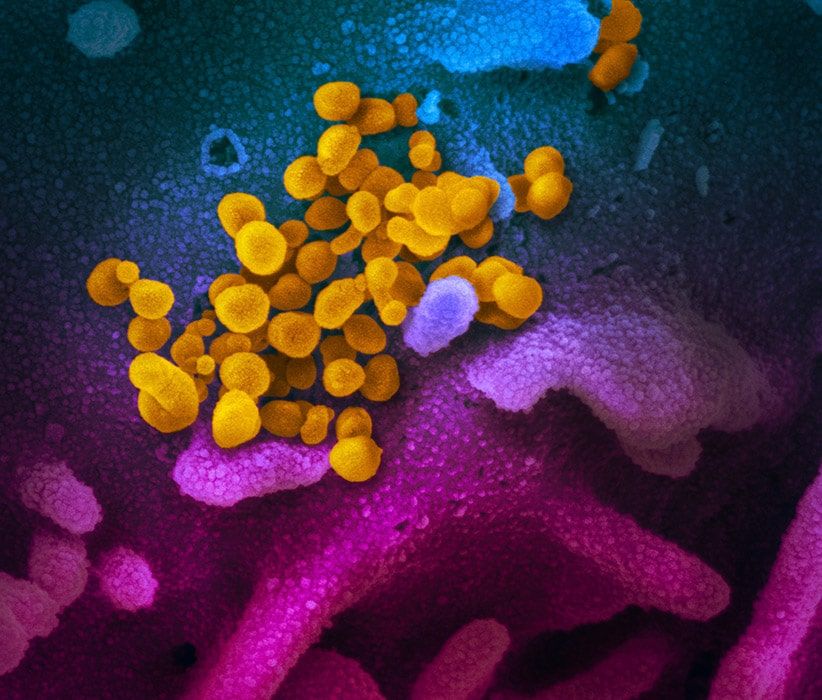

Scanning electron microscope image of the virus that causes COVID-19 emerging from the surface of cells (blue/pink) cultured in the lab. Image captured and colorized at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Rocky Mountain Laboratories. Credit: NIAID

Scanning electron microscope image of the virus that causes COVID-19 emerging from the surface of cells (blue/pink) cultured in the lab. Image captured and colorized at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Rocky Mountain Laboratories. Credit: NIAID

COVID-19 has been highly documented in social media, with about 208 public groups on Facebook devoted to the disease, and a total of about 6.5 million people getting information about it from social media sources, the Columbia Journalism Review reports.

But social media has also been used to rapidly spread disinformation and misinformation about the pandemic. And there has also been a more subtle problem: A goodly amount of the material is coming from the top-down, in the form of press briefings, official pronouncements and the like from the White House, Number 10 Downing Street, and the Élysée Palace.

Which will probably affect how the impact of the virus is written up in the history books.

But what if future historians had a reservoir of material to draw upon that comes from the bottom-up, from those directly affected? And what if it included not just the stories of people in major cities in advanced Western countries, but the perspectives of those living in Burundi, Uganda, Russia, Iraq, and Ethiopia as well?

With this approach in mind, Geneva, Switzerland-based physician Tammam Aloudat set about creating the Facebook group known as the People’s History of the Coronavirus. Its goal is to document the virus’ impact and bear witness, and the organization seems to have struck a nerve: The group went from zero members to over 6,000 in the space of seven weeks. Because he was formerly a medical doctor with Doctors Without Borders and the International Red Cross/Red Crescent and had worked in troubled places throughout the globe, the Syria-born Aloudat was well aware that people living in emerging nations faced very different challenges than those in wealthier countries, and he wanted to include their reports in the conversation. As a doctor who now worked in an office as a public health expert and administrator, he knew that the soldiers in the trenches of medical care have a perspective that differs from the view of the generals, up on the hill. He explains more, in this interview with Dan Drollette Jr., the Bulletin’s deputy editor.

(Editor’s note: This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity and brevity.)

Drollette: Where did the inspiration for the People’s History of the Coronavirus come from?

Aloudat: A number of places.

I was partly inspired by a comment in a book I was reading, called “Peacemonger”—it was written by someone who had been Under-Secretary-General at the United Nations, Marrack Goulding, and told what it was like to be head of the organization’s peacekeeping operations in the field, in places like Iraq. And there is a period in it where he says he doesn’t remember what happened, because his hand was injured and he was not able to write in his journal.

I thought: “Wow, that is an interesting fact—you really do need to write things down to remember them.” It turns out that we miss so much of our lives due to the fickleness of memory.

At the same time, I ran across this really great oral history by Svetlana Alexievich, who won the Nobel Prize in literature for her writing about things like the Soviet war in Afghanistan—a book that involved thousands and thousands of interviews, with individuals who were directly involved. The result of her work was a completely different view on history from what we usually get; the Soviet government at that time was shipping dead soldiers home in metal boxes that were welded shut, because they didn’t want to even acknowledge that they were sending soldiers to Afghanistan. What Alexievich did upended that.

And then a historian whose name I can’t remember tweeted that people should write about what they are going through during this big pandemic—and he suggested they do it by hand, in case everything collapses.

So all these strands pulled together.

But I thought that rather than wait for a historian to go around and collect handwritten notebooks from people a few months or years from now, we should collect it all now, right away, while it’s fresh—and do it in electronic form. It would be silly to compile oral histories about the coronavirus the way they did 50 years ago, when we have the tools to do it so much faster and better. So without thinking much more about it, I created this Facebook group

I expected it would get probably about 50 people—who I would probably all know personally.

But after I sent out an invitation, there were a thousand people on it by the end of the day. Three days later, there were 2,500 people, and it grew exponentially from there. It’s slowed down now, thankfully. But I didn’t anticipate it would catch on like this.

Drollette: What are the backgrounds of the people who join? Are they all medical professionals like you?

Aloudat: A good number of them are. I have a lot of friends who come from similar backgrounds, who have worked in the medical field or for nongovernmental organizations like the UN, the Red Cross, the Red Crescent, or things like that. But the backgrounds of those in the group quickly expanded a lot beyond that, though I haven’t sat down and combed through the profiles of every single person who has joined.

Drollette: Do you try to vet every person who posts?

Aloudat: No, but I do try to keep out fake accounts or trolls, and make it a place for real discussion.

I took the advice of my sister, who is a lawyer. She told me: “Now that you have created this, you have a responsibility for it, because people shouldn’t be bullied or harassed. You need to have rules that at least clearly state what’s acceptable and what’s not.”

In any case, by the evening we had a thousand people—and then each of them started inviting other people. So then I thought “I should get ahead of this,” and made it into a closed group, meaning that any potential new member from the outside needs to request to be added, although existing members can add someone as well.

But nearly all of what these people have submitted has been good; I think we’ve had maybe one deletion that I know of, out of the 100,000 posts, comments, likes, and reactions that Facebook’s statistics say have been generated on it in the past seven weeks.

Drollette: What things are people are typically submitting? News items, calls for political action, poems, diary entries, songs, artwork…

Aloudat: It’s a little of everything. I encourage people to submit whatever they feel like. I don’t want to tell people what to write or not write. In my view, whatever people post is part of their experience of this pandemic.

But I have noticed that what is coming in now is slightly different from what it was in the first couple of weeks. The tenor of it has gone from purely just very stressful news to also include war memes and jokes; it’s funny how things change so rapidly.

And that’s also an expression of the collective mindset—you know, we’ve all gone from absolute fear to dark humor as well.

But people seem to appreciate all of it. With the news items, for example, people have told me that they appreciate the level of scrutiny that the group subjects the news to. Because we have quite a few hands-on, working physicians, if some unreliable news is posted, people can ask the group “Is this true?” and get a reliable answer. Members like to scrutinize these things, evaluate them, and get a sort of general group opinion about them. Though what we have to offer shouldn’t be taken as medical advice; it’s more a case of a place where people can get a sense of the general expert opinion about a news item and make their own judgment about its validity.

Drollette: Were there any surprises among the submissions?

Aloudat: One thing I did not expect was the amount of writing about extremely personal experiences from all over the globe, especially in the first four weeks. (Note: Such items continue even now, the latest post on the group as of the time of this writing begins: “It is the middle of the night here in Bujumbura, Burundi. I am sitting on my terrace overlooking lake Tanganyika, trying to process the phone call that I answered today. It was my sister in Britanny, France, informing me that my dad had just passed away. My father’s death was in no way COVID-19 related. He had a heart attack while taking his morning confinement walk with my mother. I find solace in knowing he did not realize what was happening. Now I am sitting here in Bujumbura, helpless and clueless. The airport is closed until further notice. It could be weeks, or even months, before I can get home to my family. I need to figure out a way to pay my respects—I cant come to terms with the idea of a Facebook live burial.”)

Those are what touched me most, from people who are going through very intense, very difficult situations—involving things I wouldn’t feel comfortable telling even my closest friends. There were accounts of the psychological struggles some people were going through in trying to social distance themselves from parents and families, for example. Or what it was like to be old or infirm, and face this thing alone.

A lot of people replied with expressions of support, or shared similar stories, or wrote the person making the post to say that they were available to talk privately, off-line, on Skype or WhatsApp or something similar. People were open to talking with complete strangers and comforting them. I could not have imagined someone telling about their vulnerabilities to 6,000 other people. I won’t repeat one in particular, because it’s actually quite tough to tell, and the story still belongs to that person. But this kind of opening-up has happened so frequently, it’s not an anomaly.

And that is something I didn’t expect. It’s not what I thought of when I started it, but I suppose it has something to do with people getting more comfortable with the group as time went on.

But there’s also been a lot of lighter content as well—such as cartoons and jokes, in addition to the heavier stuff. And we’ve had very positive stories too; the tenor of the group has reached a kind of equilibrium.

Drollette: It sounds like it has become a sort of collection that documents life in the time of coronavirus. Have you gotten any feedback from historians?

Aloudat: Nothing formally yet, though I have received passing comments.

Drollette: What are your plans for the future?

Aloudat: I want to find a way to properly preserve these materials here for the future, while being aware of the situation with the creators’ rights and copyright. And I was contemplating doing a podcast where I actually asked people about their experience.

And if I could just add something here about the nature of this Facebook group—I do realize that the People’s History of the Coronavirus may not be completely typical of everyone’s experience of the pandemic, worldwide. By its very nature, this group is composed of people who are tied in to the digital world. And while there’s no doubt that this is a very diverse group, there is also no doubt that it is heavily skewed toward richer countries—people who have computers or smartphones and a reliable internet connection, and who can afford it all, for example. And most of the people on this group can afford shelter, and can afford to live in isolation for a time as well. So it’s definitely skewed that direction.

And while we get posts from all over the world, most of the people still come from the United States, the Netherlands, England, and Ireland.

So while the group might be bigger and more encompassing than the narrow view of a single historian, it definitely still has some biases; it probably is still not a truly representative sample of all those afflicted by the coronavirus.

So I think it’s important that we acknowledge that try as we may, what we collect here will not be 100 percent representative—but at least it’s a start in the right direction, attempting to tell posterity what life was like in the time of coronavirus. It’s the components of the first rough draft of history—a collective, warts-and-all narrative of life at this extraordinary time.

Even with the limitations we’ve talked about, there is still a diversity of viewpoints, from people who all have one thing in common: They’re sharing a risk. And they’re sharing with this community their struggles with that risk, and by sharing, it’s easier to empathize with them.

Drollette: Even in a place as reserved as Switzerland?

Aloudat: There was actually a meme about that on the group. After the authorities here in Geneva said that people should keep at least one-and-a-half meters between them, the Swiss asked: “Why so close?”

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: COVID-19, Coronavirus, science communication

Topics: Analysis, Biosecurity, Special Topics