Infodemic Monitor

Fact-checking networks fight coronavirus infodemic

By Jan Oledan, Julia Ilhardt, Giorgio Musto, Jacob N. Shapiro, June 25, 2020

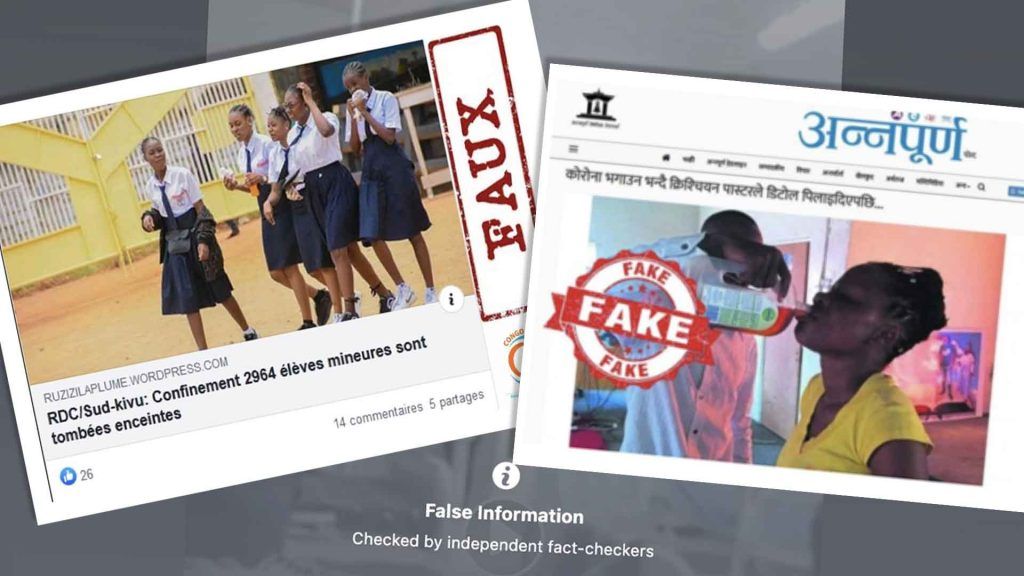

Organizations around the world are fact-checking misinformation about the coronavirus. Credit: Bulletin.

Organizations around the world are fact-checking misinformation about the coronavirus. Credit: Bulletin.

Want protection against the coronavirus? Here’s a tip: As you leaf through the pages of a Bible, you will most likely find a single hair. Put this hair into a cup of water and drink it. That’s all you need to do to become immune to COVID-19. And perhaps you don’t need to worry in the first place. Maybe COVID-19 is not such a serious disease to begin with—there’s video footage, after all, of hospital patients dancing and laughing in face masks.

But before you reach for a glass of Bible hair or underestimate the coronavirus, know that these are just two examples of the many online COVID-19 whoppers that an international web of fact-checking organizations has found and debunked.

While physical responses to the ongoing pandemic—stay-at-home orders, social distancing, and lockdowns—have been effective in mitigating the spread of the virus in many countries, misinformation remains rampant online. The World Health Organization calls the situation an infodemic: a deluge of information that people face as they seek reliable guidance about the pandemic. Miracle cures, virus-related false conspiracy theories, and overly optimistic assessments of the pandemic situation have cropped up in seemingly every corner of the globe. But these days social media users and news consumers in countries ranging from Nepal to Syria to the Democratic Republic of Congo are better equipped to deal with the spread of coronavirus-related misinformation than they otherwise might have been. That’s in part thanks to the growth in recent years of an international network of fact-checking sites like Congo Check, which debunked both the dancing coronavirus patient story as well as the one about a hair-based cure for COVID-19.

For their part, Facebook and Twitter have been steadily taking COVID-19-related misinformation down or presenting users with links to fact-checks, after having been heavily criticized in the past over slow or ineffectual responses to disinformation. Facebook, for example, collaborates directly with several organizations within the Poynter Institute’s International Fact-Checking Network. If you now visit Mao Zigabe’s Facebook post about the dancing coronavirus patients, you’ll find the video grayed out. A notice warns users that the post contains “[f]alse information [c]hecked by independent fact-checkers."

So what have these fact-checking websites, scattered across the globe, found? The Japanese site Netlab reported on chain messages (untraceable messages similar to chain mail from the days of postal mail that are spread online in an attempt to cause alarm, stoke panic, or scam recipients) that Japanese Red Cross officers were allegedly sending to warn of the inevitable collapse of the country’s health care system. In South Korea, AjuNews debunked false accusations that President Moon Jae-in was supporting a mask cartel comprising his cronies. Jordan’s Fatabyyano fact-checked the false claims spreading in Arabic-language social media spheres that Italian doctors were accusing the World Health Organization of outright denial of the coronavirus pandemic. Fact-checkers have called out hundreds of these claims since the pandemic began late last year.

Websites devoted to fact-checking are nothing new, of course. Earlier this century, Factcheck.org (established in 2003) and Politifact (2007), were founded to debunk false claims made by political leaders. By making it more costly for politicians to lie, these sites aimed to do nothing less than improve American politics—doing so by equipping the average citizen with the perspectives and tools to make informed decisions within the political system.

The same approach is being pursued in the ongoing pandemic, and many established sites have pivoted towards fact-checking coronavirus-related misinformation.

Some of the most prominent of these international fact-checking websites are extensions of existing media conglomerates. In January, the Agence France Presse website set up dedicated pages that focus specifically on coronavirus-related misinformation; in February, FactCheck Initiative Japan did the same, and in March, so did Maldita, a Spanish platform. These are just a few examples of such mainstream media coronavirus fact-checking sites; several grassroots organizations fact-check COVID-19 misinformation, as well. The latter are frequently citizen-led and rely on volunteer networks and groups of independent journalists to contribute fact-checks.

Outrageous claims. Across the globe, fairly sophisticated tools have been used to debunk misinformation, with a fair amount of success. In war-torn Syria, Verify-Sy uses forensic media tools such as reverse photo searches to monitor media of “various political and religious background[s], in order to verify it and correct it.” Verify-Sy recently debunked a viral post on Facebook and Twitter that purportedly showed a COVID-19 positive woman wearing personal protective equipment while she cradled a cancer-stricken infant. The photo was actually from 1985. In India, Pankaj Jain, a Mumbai businessman, started Social Media Hoax Slayer to deal with what he called “various lies, pranks, [and] rumors forwarded” on WhatsApp. The website used a video analysis tool to fact-check a claim on social media that a bank branch’s employees had all tested positive for COVID-19 after one had gone out and bought liquor for the group, an example of disinformation that spread as India was coming out of a lockdown and once again allowing, for instance, liquor sales.

Larger players, in particular the Poynter Institute for Media Studies, are helping to build global fact-checking capacity. Poynter hosts the International Fact-Checking Network, and supports various fact-checking initiatives around the world, providing them with training and publicity and generally encouraging volunteers (so-called netizens) to contribute to fact-checking projects. Region-specific websites that are part of the network, such as AfricaCheck, South Asia Check, and Latam Chequea, provide localized support and training. The groups have to follow a code of principles: a commitment to non-partisanship, fairness, and standards of transparency about sources, funding and organization, as well as an open and honest corrections policy.

Since March, we, along with several college and graduate students at Princeton and other universities, have been cataloguing COVID-19 disinformation narratives in countries around the world. Team members have diverse language skills that allow them to read fact-checks from various countries. So far we’ve tallied some 1,401 narratives. In every country we looked for misinformation, we found local organizations central to revealing falsehoods—including in countries as widely separated as Jordan (Fatabyyano and the state-sponsored Jordanian Media Credibility Monitor AKEED), Nepal (Nepal Fact Check), and Germany (CORRECTIV). Collectively, these organizations make it all-but-impossible for blatant falsehoods to go unchecked—at least once they hit a larger audience.

AKEED, for example, reported distorted photos and misattributed video clips—such as one of lions roaming streets in Russia to enforce a nationwide curfew. Nepal Fact Check debunked a story on a news website in Nepal about a pastor in Kenya telling fellow church-goers to drink Dettol, an anti-septic disinfectant, to get rid of the virus. CORRECTIV fact-checked a ludicrous claim that criminals in Germany were distributing free face masks laced with narcotics to exploit and rob citizens who fell prey to their trap. Some bogus COVID-19 claims are of an even more serious variety; some, for instance, target minorities within a country, or deal in virus-related conspiracy theories that could impact international relations. Fact-checking websites proved useful in disputing these claims—some of which, while outlandish, were just believable enough to be mistaken as true.

How effective is fact-checking? The evidence is mixed. In one set of experiments, 60 percent of subjects reported correct information after being shown a fact-check. On the other hand, after an influential study appeared in 2010 by political scientists Brendan Nyhan and Jason Reifler, many researchers believed fact-checks caused a so-called backfire effect where the corrections simply reinforced incorrect beliefs. Subsequent studies, though, have largely shown fact-checking can work. How the corrections are delivered appears to matter a lot; if the checks come from what the subject considers to be a credible source and the misinformation is debunked early, the better. Convincing people with strong beliefs, however, is probably a quixotic task.

There is good news when it comes to COVID-19: Claims are easy to debunk once there is enough attention. Scholars and nongovernmental organizations can use the rich base of readily available evidence and compiled data to understand coronavirus misinformation and the evolution of stories. Researchers can pull phrases from fact-checks that may enable further study on the spread and impact of COVID-19 disinformation. Most importantly, internet platforms and governments can leverage this robust ecosystem of fact-checking websites to moderate, down rank, and discourage sharing of misinformation. The strength of the ecosystem is obvious. We should not forget the broader lesson here; there is a rich grassroots community around the world which values truth, and is working hard to expose misinformation.

It’s a community can help us all do better at managing future infodemics.

(The authors would like to thank Nicola Bariletto, Alaa Ghoneim, Fumika Mizuno, Sameer Rana, Mehulika Sitepu, Kamya Yadav, Audrey Yan, and Luca Zanotti for their contributions.)

Editor’s note: This is the first installment in a series by researchers working with Princeton University’s Empirical Studies of Conflict’s COVID-19 disinformation project. Led by professor Jacob Shapiro and Jan Oledan—a research specialist for the conflict studies project—students at Princeton and other universities are cataloguing the various false narratives cropping up online about the COVID-19 pandemic. Readers can see the team’s disinformation spreadsheet here.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Coronavirus, Disinformation, Infodemic Monitor, fact-checking

Topics: Analysis, Disruptive Technologies

Share: [addthis tool="addthis_inline_share_toolbox"]