Grey-headed flying fox bats in Byron Bay, Australia. While not considered a major threat to people, the bats do carry zoonotic pathogens, including a rabies-like virus. Credit: Carlyn Kranking.

From Chicago to Uganda, scientists track the wildlife diseases that could infect humans—or spark the next pandemic

By Carlyn Kranking, January 19, 2021

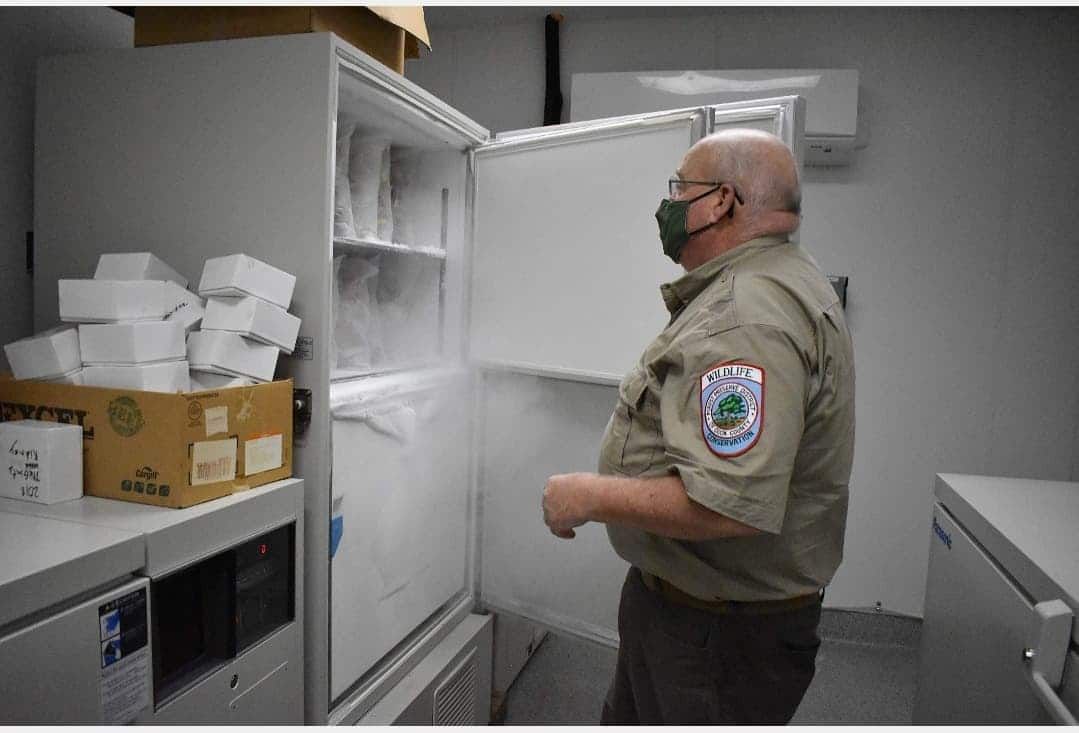

The lab is in an unassuming rectangular building on the side of a standard, flat Illinois road. Inside are offices, a laboratory, aquariums with endangered species of fish, and thousands of preserved ant and bee specimens. In a storage room in this Elgin, Ill., lab, ultra-low temperature freezers line the walls. There is one thing, however, that makes these otherwise nondescript containers stick out: a yellow sticky note with the words “Raccoon blood FULL.”

Chris Anchor maintains these freezers at around -80 degrees Centigrade, cold enough to preserve the animal blood and tissue samples inside, some of which date back to 1986. Anchor, a wildlife biologist with the Forest Preserve District of Cook County, uses these samples to monitor local animal populations for diseases with the potential to infect humans.

Anchor can look at the history of disease in the county’s animals by pulling samples and testing them for antibodies to past infections. Using data from transmitters that record animals' locations, he can predict how diseases will travel across the region. And he notices which pathogens are staying the same and which ones are mutating and evolving. At a local level, Anchor is doing what scientists are attempting at a global scale: surveilling the pathogens in wildlife that could pose a threat to humans or animals. These pathogens are known as zoonotic; they can leap from animals to humans. Experts consider such disease surveillance as being key to avoiding another pandemic like COVID-19. In the forest preserves around Chicago, Anchor is working to prevent human infection.

“By maintaining that understanding of what [diseases are] actually out there and what’s happening, it keeps us one step ahead,” Anchor said. “It allows us to be proactive instead of reactive.”

Many of the most threatening pandemics in history—including HIV/AIDS, Ebola, and COVID-19, which is thought to be linked to bats—spilled over from wildlife populations to humans. Over the last century, scientists believe about two viruses a year have been passed to people from their natural animal hosts. Identifying emerging infectious disease threats in animals before they can spread into human populations may help quash a future outbreak before it begins.

Wildlife diseases

Pathogens can “spill over,” or spread to humans, in a few ways. Contact with animal bodily fluids or surfaces contaminated by animals, consumption of infected meat or contaminated water, as well as contact through a vector like a flea, mosquito, or tick could all spread zoonotic diseases to people.

The Forest Preserve District of Cook County hired Anchor in 1986 when a study found that the deer population in Illinois had grown too large. Initially, Anchor’s principal concern was managing the county’s urban deer removal program. Last year, this initiative provided over 16,000 pounds of venison to food pantries in the Chicago area, Anchor said. He took an interest in disease and tested meat from the program to tell what infections the animals were exposed to. Though his job began with deer, it’s grown much broader, and his lab now handles about 900 to 1,500 animals each year.

Anchor and his colleagues do more than just identify diseases; they try to trace their paths. In the past, epidemiologists generally didn't track contact rates between species, Anchor said. But he is doing just that by attaching transmitters to animals like deer, coyotes, bats, and fish. “When animals interact with each other, there's a record made of it,” he said. “You can follow how disease moves across the landscape.”

When local skunks and raccoons got sick with distemper in the 1990s, Anchor used these transmitters to find the source of the viral disease, which can cause diarrhea, vomiting, coughing, and other symptoms in animals. The animals had been pilfering trash cans in the forest preserves, “coming nose to nose,” Anchor said, and spreading the illness.

What Anchor is doing on the local level in Cook County is being done on a massive scale around the world. One key effort began in 2009. A United States Agency for International Development program called PREDICT has detected over 1,100 viruses, including 949 that were previously unknown. Despite an impressive track record, PREDICT may be just scratching the surface. The Global Virome Project, a scientific collaboration aiming to catalog 99 percent of all zoonotic viruses with the potential to become pandemics or epidemics, estimates there are over 500,000 still undiscovered zoonotic viruses.

Ultimately, Anchor hopes to create a similar catalog-like resource for Cook County. Before he retires, he wants to enter all of his data into a spreadsheet, including geographic information of animals’ home ranges. This would show where animals’ habitats overlap and determine where there is potential for disease transmission.

RELATED POSTS

Preventing pandemics

Zoonotic diseases come from animals, but human activity makes it easier for these infections to spread. As development creates more opportunities for contact between humans and animals, the chance of a viral spillover event increases. “There are general things we're doing to the world that are creating conditions that favor the emergence of zoonotic diseases,” Tony Goldberg, a disease ecologist and professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said. “The ultimate solution is to stop those drivers, but that's easier said than done.”

His research targets areas where humans and wildlife come into unusually high rates of contact, like the zones on forest edges. Goldberg has done research in Kibale National Park in Uganda. Population growth around the biodiverse park means people and animals are living closer together. He’s seen domestic livestock grazing near monkeys and children getting water at the same place where baboons are drinking—both potentially risky scenarios.

“These edges tend to be dynamic areas where animals come out a little bit [and] people go in a little bit,” Goldberg said. “It's not just Africa; we have them in North America and Europe. They’re any place where there's a boundary between wildlife habitats and human habitats.”

To make the world safer from pandemics, humans should have less interaction with wildlife. Instead, people are accelerating it. Deforestation breaks down the edges of natural areas and creates “launch-pad zones” for virus transmission, Princeton University evolutionary biologist Andrew Dobson and his colleagues wrote in a July article in Science.

“If you look across the Amazon in areas that have been deforested, there’s—in the four to five years following deforestation—huge increases in rates of vector-borne diseases,” Dobson said. “People getting not only novel diseases, but diseases that have been there for a long time: malaria, dengue fever.”

Dobson’s article highlights the live animal trade and intensive agriculture as dangers to global health. Both of these activities pack large numbers of animals together, allowing disease to spread rapidly. “When pathogens spread, they have the opportunity to evolve and to potentially attack people,” Goldberg said.

Climate change, too, may be creating more opportunities for spillover. As the planet warms, animals can migrate and move into new habitats. Some species may move toward the poles to seek cooler environments, while heat-loving animals may expand their territory to areas that are warming. Some of the solutions to mitigate climate change—for instance, reducing deforestation—could also help reduce spillover risks by keeping disease-harboring animals in forests.

This shift in where animals live can accelerate disease transmission: In the highlands of Ethiopia and Colombia, warmer temperatures allowed mosquitos to live at higher altitudes, resulting in an increase in malaria distribution, according to a 2014 study in Science.

Back in Illinois, Anchor believes he has seen the effects of climate change over the course of his career. He never saw the lone star tick when he started his job in 1986, but the insect has been expanding its range northward and appeared in Cook County in the 1990s. The authors of a 2019 article in the New England Journal of Medicine wrote that the expansion of the lone star tick’s territory is “consistent with climate change,” though they noted that populations in New York are genetically different from lone star ticks in their more southern historical range. The tick is associated with numerous diseases, such as STARI, which can be misdiagnosed as Lyme disease.

“Rising global temperatures, ecologic changes, reforestation, and increases in commerce and travel are all important underlying factors influencing the rate and extent of range expansion for ticks and tickborne pathogens,” the researchers wrote.

COVID-19 isn't the end

There are steps society can take to reduce the risks of zoonotic spillover. Dobson, the Princeton biologist, and his colleagues recommended pandemic prevention measures and estimated their costs. Their strategies included ending the wild meat trade in China, reducing world deforestation by half, limiting spillover from livestock, monitoring the wildlife trade, and operating surveillance programs to detect and control zoonotic diseases. According to the paper, using their recommendations for 10 years would cost only 2 percent of what COVID-19 has cost the world so far.

“Since that paper has come out, the estimates of the cost of COVID have doubled,” Dobson said. “So that 2 percent drops to 1 percent, which makes it an even better deal.”

With the proper steps, humans can minimize the risk of another zoonotic outbreak. Some steps are big, like reducing deforestation, reforming intensive agriculture, and ending the live wildlife trade.

“If we could stop the international wildlife trade, I think we would effectively halve the risk of new pandemics occurring,” Dobson said.

Smaller steps, too, have a place in pandemic prevention. Anchor emphasizes the importance of educating both individuals and physicians. “Most of the zoonotic diseases, if you come down with them and you present yourself at an emergency room, it looks like the flu,” he said. “It’s fever; it’s body aches.” Doctors need to understand which zoonotic diseases exist in order to give accurate diagnoses and monitor conditions spreading through patient populations.

For a way out of the COVID-19 crisis, all eyes are on pharmaceutical companies and governments as they rush vaccines through approval processes and distribution. The vaccines will be critical in getting through this pandemic. But Goldberg believes a more general tool will be key to preventing future emerging infectious disease crises: education. Pandemics, he said, often originate with a poor decision by one person or a small group.

“What we need to do is change the way that people make choices about interacting with nature,” Goldberg said. “We want people to think twice before they hunt a certain species, or before they fail to take personal precautions when they interact with wildlife, or when they decide where they're going to put a big farm."

As the coronavirus crisis shows, we need science now more than ever.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent, nonprofit media organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Coronavirus, climate change, deforestation, pandemic, spillover, zoonotic diseases

Topics: Disruptive Technologies

Following the world’s viruses is a lost cause. Sealing off humans from the larger environment is a lost cause. What one can do is put in engineering barriers to stop pandemics. Water-borne viruses were stopped with sewer and clean water. If a new super virus shows up in natural water supplies, it makes no difference. Malaria has primarily been stopped by killing mosquitoes. Air-borne viruses such as the flu and Covid can be stopped by filtered air in mass transit, sealed buildings and other locations that regularly crowd people together ( https://www.forbes.com/sites/jamesconca/2020/08/11/engineering-solutions-may-be-better-for-coronavirus-than-social-ones/#416a7aa66680; https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-01-11/how-to-know-if-a-building-has-good-ventilation). These solutions work against all parasites–from the… Read more »