Meteorologist John Morales: There’s rapid intensification, there’s extreme rapid intensification—and then there’s Hurricane Milton

By Jessica McKenzie | October 8, 2024

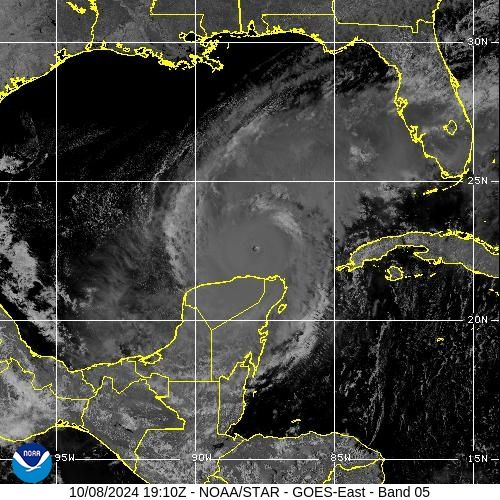

Satellite imagery of Hurricane Milton over the Gulf of Mexico. (CIRA/NOAA)

Satellite imagery of Hurricane Milton over the Gulf of Mexico. (CIRA/NOAA)

Fresh on the heels of Hurricane Helene, Hurricane Milton is barreling towards the Florida peninsula and is likely to make landfall near Tampa Bay metropolitan area, home to more than 3.1 million people, sometime late Wednesday or early Thursday. Tampa Mayor Jane Castor issued a stark warning to the city’s residents: “There’s never been one like this. Helene was a wake-up call. This is literally catastrophic. I can say without any dramatization whatsoever, if you choose to stay in one of those evacuation areas, you’re going to die.”

When Miami-based meteorologist John Morales wrote in the Bulletin last week that Hurricane Helene was a “harbinger” of the future, who knew that the future would come so soon?

I caught up with Morales in between his frequent on-air appearances on NBC6 to discuss what makes Hurricane Milton so remarkable, and so remarkably dangerous—particularly if it hits Tampa Bay head on. We also discussed what was going through his mind during an emotional moment on air, when he realized that Hurricane Milton had become a Category 5 storm in less than a day.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Jessica McKenzie: I was wondering if you could tell me what you’re seeing with Hurricane Milton, and what sets it apart from other hurricanes?

John Morales: Well, it’s yet another hurricane with a rapid intensification cycle. That we’re seeing a lot, but what really sets Milton apart was the hyper, extreme intensification that we saw, where in a span of 10 hours, the barometric pressure at the center of the hurricane dropped by 50 millibars. I know that’s kind of a technical term, but for a meteorologist, that is an astounding drop in barometric pressure. And when the pressure drops, the wind speeds follow. The wind speeds increase, because the air is trying to rush in to replace the relative vacuum of the lower pressure that is found at the center of the hurricane.

The wind speeds increased 80 knots, which is 92 miles per hour, in a span of 24 hours. It went from a Category 1 to a Category 5 in a span of 18 hours.

So on Sunday morning, we woke up to a mundane, 50 mile per hour tropical storm, but just moments before going on the air yesterday, on Channel 6 here in Miami, the news broke that it was a Category 5. So it went from a 50 mile an hour storm one morning to a 160 mile an hour Category 5 hurricane the next day at noon. So it’s just the very extreme, rapid intensification that sets this one apart.

McKenzie: And how unusual is that?

Morales: So the normal rate of rapid intensification is a 35 mile per hour increase in wind speeds in a span of 24 hours. Here, that was more than doubled. Extreme rapid intensification starts at 58 miles per hour every 24 hours. But here we saw 92 miles per hour in 24 hours.

So you’ve got normal intensification, then you have rapid intensification, then you have extreme rapid intensification, and then you have Milton. That’s what really makes the system so astounding.

McKenzie: You’ve written for the Bulletin previously about rapid hurricane intensification. Why does that make tropical storm systems more dangerous?

Morales: Well, first of all, it allows for greater damaging wind speed. So in other words, as you go through rapid intensification, it is becoming a potentially more destructive hurricane, just based on wind. But then a stronger wind speed will drive more water towards the coast. So along coasts that are susceptible to storm surge, a stronger hurricane will generally result in deeper, wider storm surge, especially if the wind field expands like is expected to happen with Milton.

The other factor about rapid intensification is that it may catch populations off guard, meaning that, people are looking at a hurricane or maybe just a tropical storm, and while forecasters might discuss, especially behind the scenes, the possibility of rapid intensification, people are not necessarily factoring that into their preparedness, that it’s not going to be just a low end hurricane or a tropical storm, and it ends up being a Category 4 hurricane. And then the perfect example is what happened with Hurricane Otis, where it was not forecast at all, and people were caught totally off guard. And the impacts were worse on that population in Acapulco, Mexico.

McKenzie: My understanding is that Tampa Bay, where Hurricane Milton could make landfall, is extremely vulnerable to storm surges. Could you explain why that is?

Morales: The exact track of the hurricane across the Gulf Coast of Florida is going to make all the difference for Tampa. If it strikes in Tampa Bay or just north of Tampa Bay, it is a worst case scenario for Tampa Bay. If it misses them, just to the south, they’re going to be fortunate yet again, to escape this worst case scenario.

Why is it so? Why are they so vulnerable to this? First of all, there is a high, high concentration of things in harm’s way in Tampa. That area has been built up enormously over the decades, and you just have so much property and so much population that is concentrated around those communities around Tampa Bay, which is a rather large bay. There’s just more things that can be damaged and more lives that can be taken. The other factors have to do with geography and have to do with unique aspects of Milton.

So first: geography and bathymetry, which is the shape of the bottom of the ocean. Florida is on a continental shelf. So off the Gulf Coast of Florida, the waters are shallow. They’re shallow for many miles, and as you push a large, amount of water towards the shoreline, because it’s not deep there, you basically have no room to store that water. The water is going to climb higher as the surge approaches the coast, simply because it’s just not deep enough to be able to accommodate all the water that’s heading towards the coast.

So you’ve got that, you’ve got the shape of the Bay, which will help catch, if you will, all that water. And then you’ve got the angle of approach, having a hurricane moving from west southwest to east northeast, in a fashion where it could hit the Gulf Coast of Florida at a perpendicular angle. That makes the surge much worse, because it spreads it over a larger portion of the western state of Florida, and because of the counterclockwise circulation around a very powerful hurricane, the waves and the water are just approaching the coastline, basically in perpendicular fashion, so it’s going to make the surge deeper. This hasn’t happened since the 19th century. You have to go back to the 19th century to find a hurricane approaching the west coast of Florida at a perpendicular angle, which was not the angle that Ian had, or Helene had, or Debbie or Idalia, or any of these hurricanes recently. None of them have had that angle of approach to the west coast of the Florida peninsula, like this one has, and that’s what makes this danger so high.

McKenzie: And then how does this storm coming so close on the heels of Hurricane Helene exacerbate the risks?

Morales: Well, first off, there’s tons of debris. And by debris, I don’t mean broken mangroves, okay? I mean people’s stuff that was left in the wake of Hurricane Helene, all along the coast of Florida, particularly in the Tampa Bay region, where they saw a seven-foot storm surge, and up the coast towards Cedar Key. And Cedar Key also has the possibility of seeing another deep storm surge in this particular hurricane. Keep in mind, each cubic yard of water weighs 1,700 pounds. So as all that stuff gets picked up, starts to float around and be driven by waves and water, it’s just going to damage more property along the way. So I think that’s a factor.

I think the saturation of the ground is another factor when we’re talking about inland flooding risk, which there is here, because we’re talking about 15 inches of rain for some locations in Central Florida, so river and flash flooding is a likely outcome.

And then, this has nothing to do with the previous hurricane, but I can tell you that this one’s going to keep its intensity longer inland, and places like Orlando are looking at potential wind gusts of 100 miles per hour, and they haven’t seen anything like that since Hurricane Charlie in 2004. So the wind impacts inland will also be quite severe.

McKenzie: There has been a flood of climate and disaster disinformation following Hurricane Helene, and I think one can expect it to follow Hurricane Milton as well. How is that impacting your work as a meteorologist and climate communicator?

Morales: Let me refer you to my writings on this very same subject, on the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. We’re seeing it play out in this post-truth era, in ways that’s really damaging society. And I’m not talking more in the psychological, esoterical ways, or maybe in the election outcome ways. This is getting in the way of emergency management agencies doing their job and saving lives and getting people out of harm’s way. It’s getting in the way of recovery efforts. It’s getting in the way of preparedness for this current hurricane threat and all future hurricane threats, because this disinformation that’s being spread out there is simply making some in our society ignore these threats and put their lives at risk. So the costs to society are just immense. And yeah, it’s definitely a hindrance to my mission as a person whose life mission is saving life and property.

McKenzie: Could you just tell me a little bit more about what was going through your head when you had that emotional moment on air yesterday, which clearly resonated with so many people, and maybe scared them a bit too? Not without good reason, Milton is scary!

Morales: So if you watch the full clip, they show the part of when they’re tossing to me. You know what a toss is on TV, right? So they have the three boxes and the anchor is saying, ‘and we have team coverage,’ whatnot, and I’m not even looking at the camera. Why am I not looking at the camera? Because I’m looking at that urgent bulletin from the National Hurricane Center that just came out in that very moment, indicating that the hurricane had become a Category 5. So I look at that. I think of how explosively it’s increasing. It’s funny because, you know, being such a nerd, but saying ‘it’s dropped 50 millibars in 10 hours’ is what made me lose it in that very moment. Why? Because that means something to me. Here we go with another explosive hurricane!

And then you mix the angst of the increase in frequency and severity of extreme weather events, which I think everybody is feeling, with empathy for the future victims of the hurricane, which, let me tell you, that’s become such a great factor in my in my life in the past 5-10 years, just seeing all these weather systems become so extreme and hurt so many people.

And then the other word is frustration. I have been talking about this for 20 plus years, trying to alert people of what was coming, trying to advocate for climate action. Nothing—or very little, has been done. Let’s say very little. Very little has been done to mitigate what’s causing global warming, and therefore, here we are. So it’s frustrating and it’s scary to think that this is just one of what will be many, many more to come. And I think that combination of, you know, empathy, frustration and angst led to that moment.

McKenzie: Especially when the impacts of Hurricane Helene were still so fresh on your mind and everyone else’s. I mean, obviously you think about hurricanes more than most, but it’s very fresh for people who aren’t always thinking about hurricanes right now at this moment.

Morales: Exactly. I mean, in the case of Florida, three hurricanes this year, right? Debbie, Helene, this one. And listen, it’s not the first time that Florida has been hit by multiple hurricanes in one year. This has happened before, including the 1920s and in the aughts. But certainly, I think everybody’s weary, everybody’s anxious, and just the sheer intensity of these systems that are jaw dropping, makes the anxiety worse.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

John Morales has been always an extraordinary professional.

The world is becoming increasingly fraught on so many fronts. And yet it is comforting, heartwarming to hear the words of a noble warrior. Thank you, Mr. Morales.

Although John is factually correct with his numbers it must be pointed out that Milton was not a zenith in rapid intensification, both Felix in 2007 and Wilma in 2005 both intensified more quickly.