Decommissioned, retired, paused: The weather, climate, and Earth science data the government doesn’t want you to see

By Jessica McKenzie | May 20, 2025

A lightning strike near Gilbert, Iowa. (Photo: NOAA)

A lightning strike near Gilbert, Iowa. (Photo: NOAA)

In the early 1990s, a University of Michigan graduate student named Jeff Masters started working on an internet weather project to share real-time weather information and satellite imagery, something most people take for granted today but was at the time revolutionary. That project was Weather Underground, which claims the honorific of being the “Internet’s 1st weather service.” It had a mission to “make quality weather information available to every person on this planet,” and promised to “provide weather data for those that are underserved by other weather providers.” Although it started as a service for universities and K-12 educators, Weather Underground became a commercial product in 1995, and for a time had more daily page views than the Weather Channel, which acquired the site in 2012.

More than three decades have passed since Weather Underground’s humble beginnings, and Masters left the company in 2019, but he can still rattle off the tools and software that he used to build the site. These include WXP, McIDAS, and LDM, all of which were provided by Unidata, a program started in the 1980s to share meteorological and atmospheric data between universities and to improve access for researchers and educators. To a layperson, these acronyms likely mean very little, but their general purpose is neatly conveyed in the name “Unidata”: a one-stop shop of universal tools for the distribution and management of data, specifically Earth and atmospheric data.

“Our little weather project was completely impossible without Unidata,” Masters told the Bulletin.

On May 12, the Unidata program paused most of its operations due to a lapse in funding from the National Science Foundation. Although it has a five-year grant from the foundation, it receives that funding in one-year increments and was due up for a new infusion shortly after the National Science Foundation instituted a funding freeze at the end of April. Now, almost the entire staff is furloughed, and the program is in limbo. It is unclear how long the funding freeze will be in effect or when the program will be able to resume operations, although a blog post on the website states, “We hope to get back to normal operations and be working with you again soon.”

It’s hard to overstate how important Unidata is to weather research and communication. “Unidata is a group that develops the underpinnings of everything we do to share weather data, to analyze it, to process it, and plot it,” Jim Steenburgh, a professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Utah, recently explained to climate journalist Andrew Revkin. “I’m gonna bet that almost any meteorological company is using Unidata software in house. Unidata, for example, has a product called MetPy, this is Python-based software, that almost anyone who does meteorological analysis uses.”

Shuyi Chen, a professor of atmospheric and climate science, told the Bulletin that virtually any university faculty member who teaches oceanography, atmospheric science, or climate science uses Unidata for research and educational purposes. But it’s not just researchers, in the United States and abroad, who depend on Unidata. These are also tools used for weather forecasting and preparing for extreme events, like floods, winter storms, hurricanes, and wildfires. She also has had students go on to work in the insurance industry, many of whom use Unidata for risk analysis.

Chen said that many people take easy access to weather information for granted. “I would ask them, ‘if there is a day that there’s absolutely no weather information communicated, what would you do?’” she said. “People are thinking that we are getting this information through private companies, but all the data, all the processing power is government-funded.”

For now, it seems that many of the tools Unidata provides will stay online, although the staff will not be able to address technical support issues. If problems arise—if anything breaks—staffers may not have the ability to respond and fix it.

But while it may not be a five-alarm fire yet, members of the weather and atmospheric science community are justifiably concerned.

“The big concern would be the IDD—the Internet Data Distribution system—because the people at Unidata help maintain that,” said Masters. The IDD initiative was started to help universities access the growing troves of environmental, climate, and meteorological data collected by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and other federal agencies for free. It allows universities to request that observational data be pushed to them as soon as it becomes available, and to share observations back with the rest of the network. “If they’ve got a technical problem, hardware issue, whatever, and there’s nobody there to fix it, then the whole IDD is at risk,” Masters said. The longer the pause of Unidata’s work drags on, the more likely it is that something will break.

Unidata is just one of the latest data projects impacted by the vast cuts the Trump administration is inflicting on federally funded science. NOAA recently announced that it is retiring the Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters database, which has tracked the damage from floods, hurricanes, and other large disasters since 1980. Twenty-two other NOAA data products have likewise been retired or decommissioned over the past month.

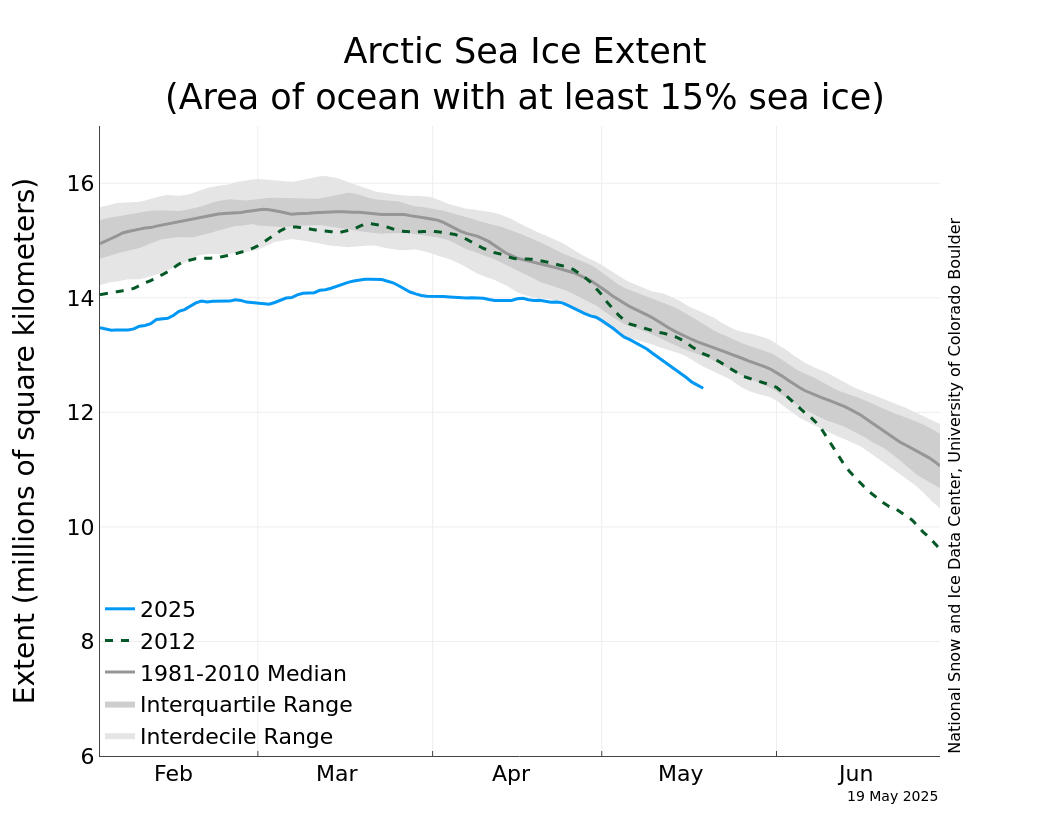

Earlier this month, the National Snow and Ice Data Center at the University of Colorado Boulder’s Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES), reported that NOAA had decommissioned some of the snow and ice data sets that it produces and maintains, including the popular Sea Ice Index.

In a recent interview with Ann Windnagel, the new manager for the NOAA program at the National Snow and Ice Data Center, and Florence Fetterer, the outgoing manager, they clarified that the data products they create and maintain will stay online for now. This includes the Sea Ice Index, which tracks sea ice changes at the poles, the World Glacier Inventory, and the Snow Data Assimilation System, or SNODAS, which tracks things like snow cover and density. But the consequences of decommissioning will mean that they have less funding and bandwidth to respond to user questions or to any problems that arise.

“One of the bigger things that users appreciate about our products is that they can write us and ask questions and get quick responses from us, and we won’t be able to facilitate that,” said Windnagel. “For the moment, not a lot is going to change for our main audience. They’re still going to go to the website every day, see the updates, download the data. But if they were to write in to us, we would not be able to respond in the same way we have. And if [the products] break, they may just go down and we aren’t able to bring them back up.”

In the decommissioning announcement, the National Snow and Ice Data Center asked people who use their products to write in to share how they use them and why they are important. Within a day, they had received nearly two dozen responses, from high school teachers and researchers, but also from someone at the Colorado Water Conservation Board, which uses SNODAS for hydrological forecasting, and from utilities districts and municipalities, including Valdez, Alaska.

Fetterer read aloud one message from an educator, who wrote: “I teach my students about climate change using data harvested from the National Snow and Ice Data Center. My students graph the data and develop important skills. They also learn to best fit the data and make predictions. They learn the value of scientific debate as they discuss the impacts of shrinking Arctic sea ice. Each year my students’ work is updated with the latest information. This is too valuable of a resource to lose to budget cuts and short sighted and scientifically illiterate policy decisions.”

“The absolute worst-case scenario, I think—and Ann may have a different opinion—is that something with the Sea Ice Index breaks, and we need developer time to fix it, and we can’t get it fixed,” said Fetterer. “The Sea Ice Index is not only an extremely popular product with scientists and the general public, it also feeds the NOAA climate.gov climate dashboard… I think the more likely case is that everything just sort of slowly degrades.”

She added that the best-case scenario is that funding is restored, but the most realistic best-case scenario is that no other funding from NOAA is lost.

“I hope that people who read what you write will consider if this matters to them,” Fetterer said, “and if it does, to reach out, not on our behalf, but on their own behalf, to their representatives.”

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Trump administration, climate data, extreme weather, weather data, weather forecasting

Topics: Climate Change