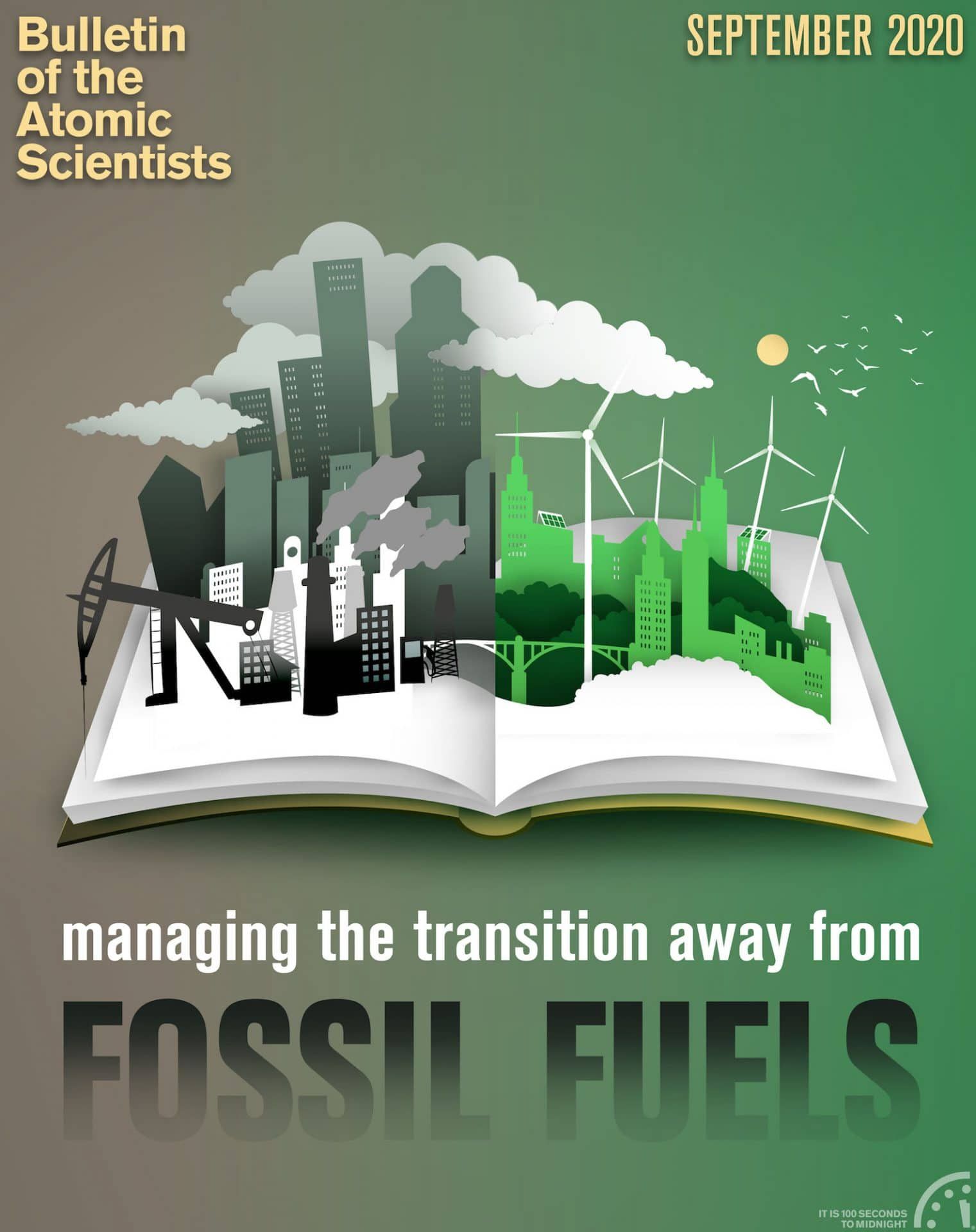

Financing a low-carbon revolution

By Neil Gunningham | September 8, 2020

A 32-megawatt photovoltaic array is being built in the southeast corner of the Brookhaven National Laboratory site. Credit: Brookhaven National Lab

Financing a low-carbon revolution

By Neil Gunningham | September 8, 2020

Loading...

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: carbon pricing, central banks, climate finance

Topics: Climate Change

Ocean tides could generate pretty much all the grid needed electricity the coasts would need. Niagara Falls provides inexpensive power to Upstate NY. Just don’t forget about the oceans.