1950: What the scientists are saying about the H-bomb

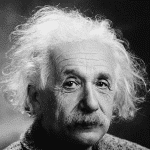

By Albert Einstein, Edward Teller | December 7, 2020

1950: What the scientists are saying about the H-bomb

By Albert Einstein, Edward Teller | December 7, 2020

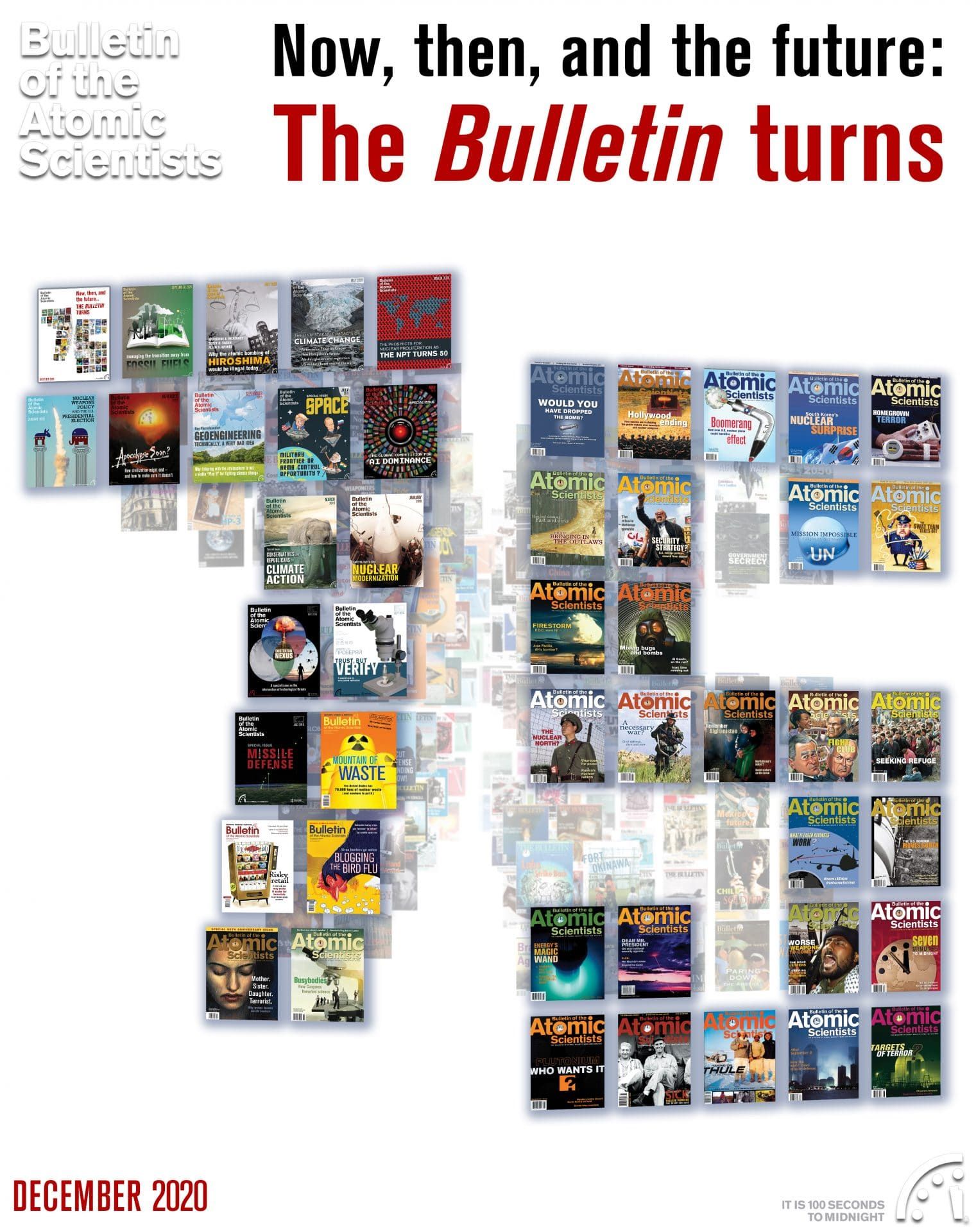

Editor’s note: These companion articles were originally published in the March 1950 issue of the Bulletin, in the wake of President Harry Truman’s announcement that the United States would pursue a hydrogen bomb. They are republished here as part of our special issue commemorating the 75th year of the Bulletin.

Arms Can Bring No Security

The idea of achieving security through national armament is, at the present state of military technique, a disastrous illusion. On the part of the United States this illusion has been particularly fostered by the fact that this country succeeded first in producing an atomic bomb. The belief seemed to prevail that in the end it were possible to achieve decisive military superiority.

In this way, any potential opponent would be intimidated, and security, so ardently desired by all of us, would be brought to us and all of humanity. The maxim which we have been following during these last five years has been, in short: security through superior military power, whatever the cost.

This mechanistic, technical-military, psychological attitude had inevitable consequences. Every single act in foreign policy is governed exclusively by one viewpoint.

This mechanistic, technical-military, psychological attitude had inevitable consequences. Every single act in foreign policy is governed exclusively by one viewpoint.

How do we have to act in order to achieve utmost superiority over the opponent in case of war? Establishing military bases at all possible strategically important points on the globe. Arming and economic strengthening of potential allies.

Within the country—concentration of tremendous financial power in the hands of the military, militarization of the youth, close supervision of the loyalty of the citizens, in particular, of the civil servants by a police force growing more conspicuous every day. Intimidation of people of independent political thinking. Indoctrination of the public by radio, press, school. Growing restriction of the range of public information under the pressure of military secrecy.

The armament race between the USA and the USSR, originally supposed to be a preventive measure, assumes hysterical character. On both sides, the means to mass destruction are perfected with feverish haste—behind the respective walls of secrecy. The H-bomb appears on the public horizon as a probably attainable goal. Its accelerated development has been solemnly proclaimed by the President.

If successful, radioactive poisoning of the atmosphere, and hence annihilation of any life on earth, has been brought within the range of technical possibilities. The ghostlike character of this development lies in its apparently compulsory trend. Every step appears as the unavoidable consequence of the preceding one. In the end there beckons more and more clearly general annihilation.

Is there any way out of this impasse created by man himself? All of us, and particularly those who are responsible for the attitudes of the U.S. and the USSR, should realize that we may have vanquished an external enemy, but have been incapable of getting rid of the mentality created by the war.

It is impossible to achieve peace as long as every single action is taken with a possible future conflict in view. The leading point of view of all political action should therefore be: What can we do to bring about a peaceful co-existence and even loyal cooperation of the nations?

The first problem is to do away with mutual fear and distrust. Solemn renunciation of violence (not only with respect to means of mass destruction) is undoubtedly necessary.

Such renunciation, however, can only be effective if at the same time a supra-national judicial and executive body is set up empowered to decide questions of immediate concern to the security of the nations. Even a declaration of the nations to collaborate loyally in the realization of such a “restricted world government” would considerably reduce the imminent danger of war.

In the last analysis, every kind of peaceful cooperation among men is primarily based on mutual trust and only secondly on institutions such as courts of justice and police. This holds for nations as well as for individuals. And the basis of trust is loyal give and take.

What about international control? Well, it may be of secondary use as a police measure. But it may be wise not to overestimate its importance. The times of prohibition come to mind and give one pause.

* * *

Back to the Laboratories

President Truman has announced that we are going to make a hydrogen bomb. No one connected with work on atomic bombs can escape a feeling of grave responsibility. No one will be glad to discover more fuel with which a coming conflagration may be fed. But scientists must find a modest way of looking into an uncertain future. The scientist is not responsible for the laws of nature. It is his job to find out how these laws operate. It is the scientist’s job to find the ways in which these laws can serve the human will. However, it is not the scientist’s job to determine whether a hydrogen bomb should be constructed, whether it should be used, or how it should be used. This responsibility rests with the American people and with their chosen representatives.

Personally, as a citizen, I do not know in what other way President Truman could have acted. As a scientist, I am troubled by other questions, more limited, more specific, but not less urgent and not less harrassing. Can a hydrogen bomb be built? How can we build it? Can we build it before the Russians succeed in doing so?

I cannot answer these questions. Even the elements which will be used in answering them cannot be mentioned publicly. But the background from which we start in our work can be discussed, and this discussion may be found relevant.

I cannot answer these questions. Even the elements which will be used in answering them cannot be mentioned publicly. But the background from which we start in our work can be discussed, and this discussion may be found relevant.

The situation should be similar to the one in 1939. I am sure that all of us remember it well. A conference comes to my mind. The scientists present were urging that work on atomic bombs should be started. We said that such bombs could probably be made. We said that the fate of the war, which had started with the crushing defeat of Poland, might hinge on atomic energy.

The colonel, who was listening to us was not interested. He had heard too much of secret weapons. He told us about a goat which he had tethered for experimental purposes on his test site. He had offered a prize to any inventor of a new weapon which could kill the goat from ten paces. (I think he had death-rays in mind—apparently the thing closest to atom bombs in his way of thinking.) The goat was still thriving. “Moreover,” the colonel went on, “wars are not won by weapons. They are won by the justice of the cause.”

Tempora mutantur. I have not met any skeptic like that colonel in army uniform in a long time. Today there is a discussion of the possibility of a new weapon; already it is considered a reality.

On the other hand, many of the scientists now think, “Peace is not won by weapons.” Ghost of the colonel!

To my mind we are in a situation not less dangerous than the one we were facing in 1939, and it is of the greatest importance that we realize it. We must realize that mere plans are not yet bombs, and we must realize that democracy will not be saved by ideals alone.

Our scientific community has been out on a honeymoon with mesons. The holiday is over. Hydrogen bombs will not produce themselves. Neither will rockets nor radar. If we want to live on the technological capital of the last war, we shall come out second best. This does not mean that we should neglect research or teaching. If we get to work now, it will be sufficient to have perhaps one quarter of the scientists engaged on war work. The load could be lightened by rotation. If we wait too long, not even the effort of all the scientists will suffice.

Do we dare to hope that all citizens in their turn will realize: democracy will not be saved without some daring ideals? I do not believe that the hydrogen bomb or the whole arsenal of technological warfare will save the United States unless we accept the fact that the United States and all the freedom-loving people of the whole world must be saved. The grim alternative is that all of us will live under tyranny.

Many of our friends are disheartened. They had some hope in the summer of 1945. But if the atom bomb did not help to establish peace, why should the hydrogen bomb? Why should anything else, for that matter? I think we should try again. The situation is now different. We have now a success and a failure behind us: The scientists enjoy the prestige of having successfully made atomic weapons; their advice may have a somewhat greater weight now. We also have had the experience of a dismal failure: We did not have enough realism, courage, and initiative at the time of Hiroshima. We did not, in fact, win the peace. We must try again; there is no other way. Such a new attempt cannot come from the scientist, however strongly he feels about the subject. The primary responsibility for action lies with the groups directing the policy and foreign relations of our country.

To the scientist, at least, it should be clear that he can make a contribution by making the country strong. And he can continue to make a contribution by explaining this dangerous world to his fellow-citizens.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Edward Teller, Einstein, archive75, h-bomb

Topics: Nuclear Weapons