Introduction: An innovative and determined future for the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

By John Mecklin | December 7, 2020

Introduction: An innovative and determined future for the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

By John Mecklin | December 7, 2020

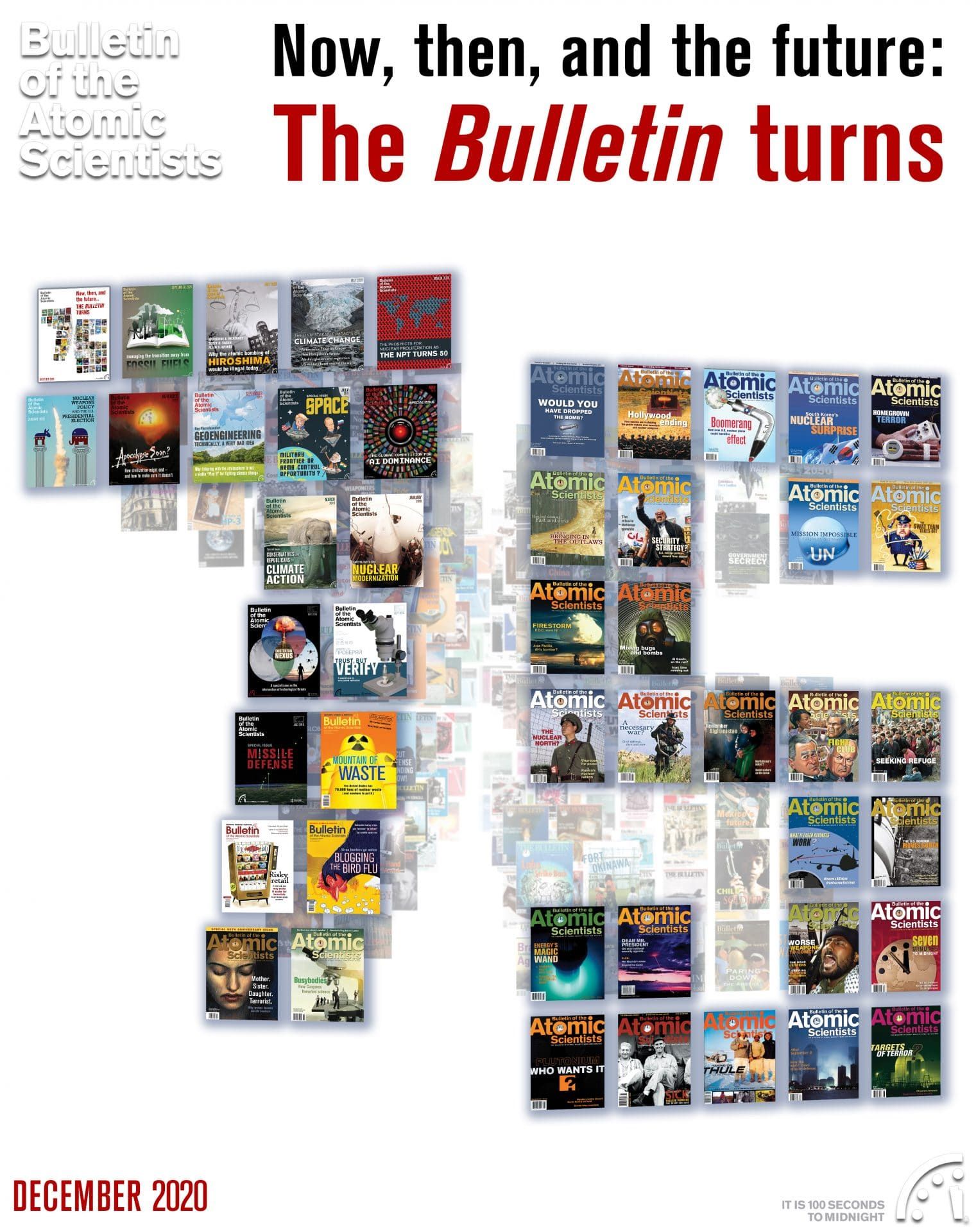

Because learning from the past is one thing and living in it quite another, this issue—which marks the start of the 75th year of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists—was assembled with a nod to history but eyes fixed firmly on the future. To avoid wallowing in the past, I quite purposely aimed the opening section of the issue at 21st century challenges, asking a diverse cast of respected strategic thinkers and doers of this era to look forward a decade or two, and to answer a general question: Where might the Bulletin and its readers most profitably focus their attention as they work to keep the Doomsday Clock from striking midnight?

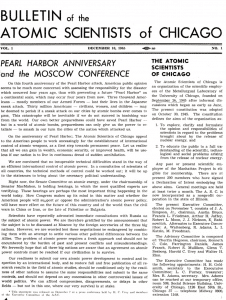

Seventy-five years after the Bulletin’s first edition—a six-page pamphlet published on Dec. 10, 1945—the array of existing and potential technological threats to civilization has expanded in ways that are difficult even to track, much less manage. Beyond the nuclear- and climate- related threats that the Bulletin has long targeted as existential (that is, as threats capable of ending civilization and perhaps even the human species), new dual-use technologies have emerged or are emerging across a wide front of quickly advancing science.

Discoveries in genetic engineering, artificial intelligence, information technology, robotics, neurotechnology, and many other fields are arriving at a dizzying pace in countries around the world. Managing these advances so they help rather than endanger humanity is a challenge as important as the one the atomic scientists faced after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Now, though, the task is more difficult; there are more global threats, they increasingly intersect, and the internet spreads lies about them instantly round the world, long before the truth can get its proverbial pants on.

Martin Rees, the UK Astronomer Royal and founder and leader of Cambridge University’s Centre for the Study of Existential Risk, described the current situation in an interview with Bulletin CEO Rachel Bronson this way: “We are in an interconnected world where we are collectively putting pressures on our environment. And where it’s possible for error or terror to lead to catastrophes triggered even by quite a small number of people. That is why, I think, we’re going to have a bumpy ride through the century, and it’s going to be a big challenge for our politicians to cope with this.”

The prospect of nuclear war and nuclear terrorism continues to loom over the complex threat landscape of 2020. Nine countries possess thousands of nuclear weapons, many on high alert, and the mechanisms for restricting nuclear proliferation are under stress. In fact, top experts believe the risk of the use of nuclear weapons is as high now as at any time since they were invented. A mistake in this realm would mean more than a bumpy ride; it could mean the end of the ride altogether. Therefore, as one might and should expect of the Bulletin, this anniversary issue includes essays by and interviews with some of the most respected experts in the nuclear policy field, including:

-

Sig Hecker Los Alamos National Laboratory director emeritus Sig Hecker, who draws from the history of nuclear arms control to suggest how it might be reinvigorated and made more wide-ranging in coming decades.

-

Emma Belcher Ploughshares Fund president Emma Belcher, who suggests that achieving transformative change in the nuclear weapons situation will require a greater diversity of thinkers and new ideas that may well seem disconcerting at first glance.

-

Bill Perry Former Defense Secretary William Perry, who describes his personal journey over the decades to become a staunch supporter of the abolition of nuclear weapons and the education of a new generation to carry on efforts toward nuclear threat reduction and disarmament.

-

Rose Gottemoeller Former NATO Deputy Secretary General Rose Gottemoeller, who explains why an interdisciplinary approach is required for success in the kind of “science diplomacy” that resulted in the world’s greatest nuclear arms control agreements—and that will be needed again in the 21st century.

-

Beatrice Fihn Beatrice Fihn, the executive director of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), who offers her views on implementing the nuclear weapons ban treaty that ICAN helped shepherd to passage and, this October, ratification.

In the 21st century, climate change is an undeniable problem to solve, scientifically documented and visible in the form of massive forest fires, increasingly severe weather events, droughts, and heat waves. For this issue, two consequential figures in climate science and policy, Princeton University’s Rob Socolow and UC San Diego’s Richard C. J. Somerville, offer sophisticated essays that present their holistic ideas on workable policies for dealing effectively with the climate crisis. I consider these nuanced pieces to be required reading for any citizen—of any political persuasion—interested in leaving a livable planet to the next generation and the many that can follow, if the Earthlings of our era act appropriately.

One-fifth of the way through the 21st century, advances in biological science and technology are beginning to bring the kind of benefits to humanity once imagined in science fiction. Thanks in part to a remarkable discovery—the gene-editing technique known by the acronym CRISPR/Cas9—cures for inherited diseases and crops that will withstand the heat and droughts of climate change are within sight. In October, UC Berkeley professor Jennifer Doudna was named a co-winner of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of CRISPR/Cas9. Just weeks earlier, she spoke with me about its revolutionary promise, the work she is doing to develop diagnostics for the coronavirus now ravaging the world and other potentially pandemic pathogens, and the need to ensure that CRISPR isn’t misused to alter humans in heritable ways.

In a broader look at biotechnology, Kings College London public health expert Filippa Lentzos writes about the potentially terrifying convergence of genomic technologies with advances in artificial intelligence, automation, affective computing, and robotics. “These game-changing developments will deeply impact how we view health and treat disease, how long we live, and how we consider our place on the biological continuum. They will also radically transform the dual-use nature of biological research, medicine, and health care and create the possibility of novel biological weapons that target particular groups of people and even individuals.” Managing the technological advances now under way, Lentzos says, will require governance structures and cross-sectoral expertise—from business and academia to politics and defense.

And in an essay that I found extraordinary for its intellectual ambition and surprising insights about the connections between science and politics, Cornell University particle physicist Yangyang Cheng argues, in part, that pretending to be above and beyond politics in these times is itself a political position. In adopting a supposedly apolitical pose, she contends, the global scientist of today aligns with the state and sides with the powerful. But what I just wrote is indeed only a small part of the philosophical journey that Cheng will lead, if you decide to follow her multifaceted exploration of the concept of borders.

***

In research ahead of this issue, I learned many interesting things that the Bulletin has addressed during its storied 75-year history but that I somehow had not previously encountered. Thanks to the Social Science Research Council and Sylvia Eberhart, I learned that in the immediate aftermath of World War II, more than a third of Americans—including those judged to have “high” levels of knowledge about world affairs—felt it likely that the United States would develop a defense to atomic weapons long before other countries learned how to make them. From a 75-year vantage and with the knowledge that there is no such defense, even now, their belief in American scientific prowess and ingenuity seems wide-eyed and quaint, if a bit disheartening.

I also learned, in definitive fashion, that the atomic bombs of the 1940s could not start uncontrollable chain reactions that would consume the atmosphere or oceans, as Nobel physics laureate Hans Bethe explains in his charming and soberly detailed article, “Can air or water be exploded?” Further, I learned that one of Bethe’s students—the British polymath and Nobel laureate in literature, Bertrand Russell—counseled the United States against developing the neutron bomb way back in 1961.

These revelations are only a tiny fraction of what you will discover while reading the latter portion of this issue, which consists of republications of noteworthy pieces that appeared in the Bulletin over the last seven-and-a-half decades. I make no representation that this retrospective is comprehensive. It could not possibly be, given the trove of famous authors and weighty subjects the magazine and its cast of talented editors have ushered into print and (as the magazine turned digital) pixels since 1945.

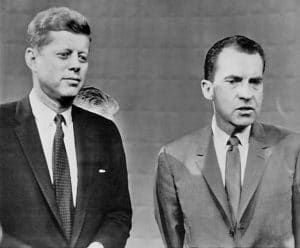

The choices of who or what to include or exclude from the issue were daunting. Did we really have only enough space to include one piece each by Einstein, Oppenheimer, Gorbachev, and the magazine’s legendary longtime editor, Eugene Rabinowitch? Were the dueling arms control essays submitted by 1960 presidential candidates Richard Nixon and John F. Kennedy of sufficient quality to push aside the work of intellectual giants like Leo Szilard,[1] who first conceived of the nuclear chain reaction; Otto Frisch, who played a role in the discovery and naming the process of fission;[2] Max Born, who won the Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on quantum mechanics;[3] and Joseph Rotblat, a co-winner (with the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs) of the 1995 Nobel Peace Prize “for their efforts to diminish the part played by nuclear arms in international politics and, in the longer run, to eliminate such arms?”[4] Would the thoughts of Carl Sagan and Daniel Ellsberg on the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War remain consigned to Bulletin archives?[5]

The answers to these questions were, unfortunately but uniformly, “yes.” Even in the digital age, a single magazine issue has a limited size, so a lot of worthy work and many extraordinary thinkers were cast to the cutting-room floor. All the same, the articles and authors that fill the historical portion of this issue are diverse and incandescent, exploding with prescient brilliance. One example I can’t help but note, again, as a matter of institutional pride: The Bulletin cover story on climate change, headlined “Is mankind warming the Earth,” written by National Center for Atmospheric Research meteorologist William W. Kellogg—and published in February 1978, long before global warming became anything like a major matter of public concern.

***

As a wise man recently reminded me,[6] important ventures ought not be planned without attending to the past. The history of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists is a remarkable one that is more than worthy of attention;[7] it is full of some of the greatest thinkers of modern times trying to grapple with a truly existential dilemma: the first invention of humankind that could exterminate humanity. In some senses, the first 75 years of the Bulletin might even be considered successful. It was founded to warn humanity of the dangers of nuclear weaponry, and since the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, no nuclear weapons have been detonated in war.

Still, nuclear weapons have been used repeatedly to threaten and extort, and the world has had so many close calls with nuclear war that no reasonable person could think the current methods for diminishing its likelihood are adequate. Deterrence theory—or mutually assured destruction, if you prefer that locution—is a thin reed on which to balance the long-term future of humanity. Deterrence is after all dependent (as Emma Belcher reminds us) on a belief that all leaders who control nuclear weapons will always behave in a rational manner. Such a belief should have been considered irrational at the Bulletin’s founding and throughout the Cold War, but to continue to hold it in our political times seems utterly delusional.

I believe now more than ever that humans can manage the technologies they create, and that the collective will to live and extend the human experiment should not be underestimated. But the present and future never belong to those who live in the past; “back to the future” is a movie title, not a strategic plan. The past can be prologue, but each era needs its own narratives. Today, those narratives will be offered by a new generation of thinkers who come from diverse backgrounds and who create effective 21st century solutions for the world’s largest challenges. The Bulletin has long been ahead of the curve in explaining existential threats to humanity in a way that is useful to experts, a general audience, and those world leaders who are willing to pay attention. With your support, we will continue to find new and powerful ways to tell the story of humanity’s most important mission: to survive.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: 75th anniversary, Albert Einstein, Beatrice Fihn, Bertrand Russell, Crispr, Emma Belcher, Filippa Lentzos, Hans Bethe, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Jennifer Doudna, Mikhail Gorbachev, Richard Somerville, Rob Socolow, Rose Gottemoeller, Sig Hecker, William Perry, Yangyang Cheng, introduction

Topics: Climate Change, Disruptive Technologies, Nuclear Weapons