Interview: Diane Randall, general secretary of the Friends Committee on National Legislation, discusses restraining the US defense budget

By John Mecklin | September 7, 2021

Interview: Diane Randall, general secretary of the Friends Committee on National Legislation, discusses restraining the US defense budget

By John Mecklin | September 7, 2021

Diane Randall has led the Friends Committee on National Legislation (often known by its FCNL acronym) for more than a decade, directing lobbying and educational efforts on issues approved by the group’s General Committee, composed of some 180 members of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers). Those issues are broad in scope, but since its founding in 1943, the FCNL has put peace and reductions in militarism at the center of its advocacy.

Quakers have also been at the forefront of advocacy against nuclear weapons and nuclear proliferation. As Randall noted in announcing her decision to become a Gender Champion in Nuclear Policy earlier this year, “Quakers, especially women Quakers, have been leading anti-nuclear efforts since 1945, after the first bombs were dropped in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. We will continue to work for the elimination of nuclear weapons and will not waver.”

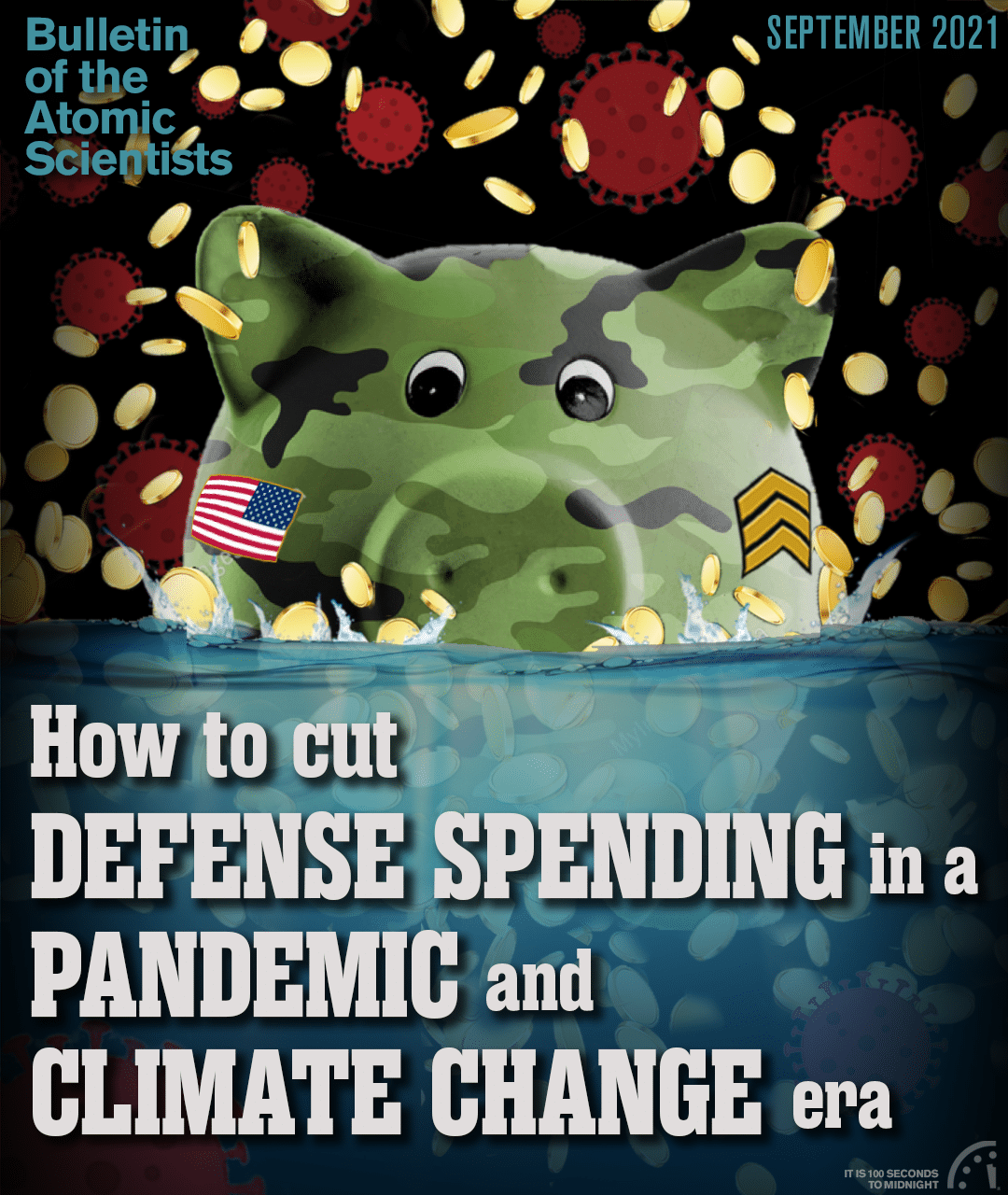

In this interview, I asked Randall about efforts to cut (or at least reduce the rate of growth of) the United States defense budget, which exceeds $750 billion annually, even though other challenges to national security—climate change and pandemic disease, to name just two—loom large.

Randall’s answers were less than optimistic about the chances for change in the short term, but, as befits the leader of an organization known for its “long game,” positive about the prospects that generational change can eventually come and reduce a US military budget that is roughly the size of the defense spending of China, India, Russia, United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia, Germany, France, Japan, South Korea, Italy, and Australia. Combined.

John Mecklin: Part of what I want to do is introduce you and your group to Bulletin readers who may not know very much about it. Why don’t you give our readers an overview of what your group does?

Diane Randall: Sure. The Friends Committee on National Legislation is a national nonpartisan, nonprofit organization that advocates with Congress on issues that are of prime importance to Quakers. We determine our legislative priorities by asking Quakers around the country, what is significant for them in relation to their own faith and practice, and then we develop those into actual legislative priorities that we advocate on the Hill. So we do federal advocacy.

We are just a little bit older than the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. We were founded in 1943 and have worked consistently for peace—to prevent war and to end war—and that includes working for nuclear disarmament and nuclear non-proliferation. We’ve also expanded to take on a number of other issues related to peace that include promotion of peace building as an alternative to war. We are not only anti-war, but very pro-peace.

We advocate for diplomacy, obviously, in all its forms, including arms control. We’ve taken on a number of justice issues. I mean, I would argue that nuclear non-proliferation and ending nuclear war is a justice issue as well, but the sort of more traditional economic justice, racial justice, immigration justice.

We have a very broad portfolio of issues that we lobby on, and this presents a real challenge at times. Yet we can weigh in with a voice that has a basis of moral conviction to what we do, which I think is the best of advocacy. We work a great deal in coalition with many, many partners based on the issues that we work with.

For example, we work with the Union of Concerned Scientists on climate change and on nuclear weapons issues. We work with J. Street and NIAC [the National Iranian American Council] and other groups on the JCPOA [Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action] and trying to reinstate the [nuclear] agreement with Iran. We work with Win Without War and other groups that are trying to limit Pentagon spending.

Just to say a little bit about the structure of the organization—we are about 55 staff, and that includes people who are lobbyists, registered lobbyists on the Hill who represent those various issue areas. It includes a field team that we call the Strategic Advocacy Team, which works with grassroots constituents across the country

People who are Quakers and people who are not Quakers, but who align with our work, we welcome all to advocate with us. It includes a finance team, obviously for the structure of the organization, human resources. We have a fairly robust development team because most of our income comes from individual contributions and from foundation support. Ploughshares has been a core supporter of ours for a long time. Humanity United, Open Society are the foundations that provide support. But that’s actually less than about 20 percent of our funding. We really rely on donors who have consistently supported FCNL even as we’ve grown and developed the organization.

Just to say one other thing is that we’re actually three different organizations that fall under the title of FCNL. FCNL is a 501(c)(4), which gives us the flexibility to lobby. We do not endorse candidates. We do not take a position in political races, but that (c)(4) designation does allow us to lobby significantly. Then we are 501(c)(3), which are the tax-deductible contributions, which is the educational work we do alongside the lobbying work.

We have now a new organization called Friends Place on Capitol Hill. It is a place for groups to come and stay to do civic engagement in an educational, experiential learning situation, which will really be focused on younger people, middle school, high school, college age. So that’s a program that we took over from another Quaker organization, and we’re in the process of restarting that.

Mecklin: This issue of the Bulletin is about restraining military spending and repurposing it for maybe something a little more useful, something a little less destructive. There are a lot of groups and people who want to restrain military spending, but we have something like a $750 billion defense budget. What’s your assessment of where that fight to cut some defense spending is right now in Congress?

Randall: Well, you’re right. A $753 billion defense budget; it’s really hard to fathom that we can actually spend that much in a year, and yet it continues to grow. It has grown in the decade that I’ve worked with FCNL. It certainly grew during the time of the Iraq War and Afghanistan War and has continued to grow despite the withdrawal of troops from Iraq and now from Afghanistan.

I think about the institution of not just the Pentagon, but the institution of defense spending, as having a vast structure and momentum that is really hard to put a brake on, because it touches so many people. I haven’t looked recently, but I imagine that there are defense contracts in the 435 congressional districts and in all 50 states.

So there’s an economic underpinning to the defense expenditures that in itself—aside from whether or not it is a militarily good idea—that has a momentum that is very difficult to intervene in. People who I work with and care about Pentagon spending frequently cite the Eisenhower quote about the threat of the military-industrial complex, and he was right. I mean, it is a vast complex, and it is hard to determine where to intervene.

I lived in Connecticut for a number of years. We have generally quite progressive lawmakers from Connecticut, who are loath to cut military spending because of its impact on [aircraft engine manufacturer] Pratt and Whitney or [submarine contractor] Electric Boat or any one of their contracts. So I think thats’ a really important acknowledgment. It’s important both in terms of the political pressures that members of Congress face and the reality of the fact that those are jobs. Those are good jobs that pay people’s mortgages.

When you think about problem-solving, you can think about what do you stop doing, what do you start doing, what do you continue doing. At some level, there has to be a willingness to stop spending somewhere, to stop spending on something.

We don’t generally lobby against specific weapon systems per se—although the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent is one that we’ve focused on and are really actively trying to determine whether we could end the spending on that. That’s a small portion of the defense budget, but when you think about the ultimate life of that new weapon system and the paradox of it ever getting used—it’s a waste of money when you think about the other threats that we are facing.

I’m kind of straying off from your core question, which was where are we with regard to Congress on this defense spending issue. The fact is that there is bipartisan support for continuing excessive defense spending in the United States. Until we can begin to have more voices calling for actual reductions and cuts—more voices in Congress and from people around the country—it will be hard for them to say no.

Mecklin: Have you done polling or have access to polling as to whether Congress matches up with public opinion on this? I can’t imagine if most people actually understood how much money is being spent for what I like to call junk in the garage—buying things that are just going to be stacked up and couldn’t possibly be used, or the world would end—I mean, how does public opinion match up to what Congress is doing?

Randall: I have to confess, we haven’t done that kind of pulling ourselves, and I haven’t looked at it. But we have been paying attention to what people want with regard to what the Biden administration has proposed in the American Families Plan or the American Jobs Plan. The fact is that there are huge majorities—both Republican and Democrat—who support the initiatives and those plans. We’re talking about a plan that’s going to essentially provide a guaranteed basic income to families with children through the child tax credit. That’s very popular, very much of interest, and it’s a big expenditure. It’s also a really good investment.

I think a lot of weaponry in the defense budget has been cast as an investment, a good investment. I do think people are beginning to challenge that assumption. In many ways, nuclear weapons are on one hand an anachronism. On the other hand, they’re very real and very threatening. But when we think about what the true global threats are—those have changed and yet our behavior hasn’t changed to address those.

I feel like what the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists has done is to try to raise these questions about what are the threats facing our country, our planet. It’s stunning how even in the last decade the threats have changed dramatically. If you think about the end of the Cold War, obviously we’ve reduced the number of nuclear weapons, which is significant. Yet we continue to develop new ones, which is not logical on the face of it. We also continue to invest so much in the military budget.

Let me just say one other thing about defense spending. All kinds of things get put into that budget that really don’t have to do with the military. In some cases, one could even argue whether they have anything to do with national security.

The question is: Is that the way we want to make decisions about the policies that govern our country? Is it through the defense budget that we should be addressing breast cancer, for example, which gets funding for research? Lawmakers have figured out that they can get funding through the defense budget, but it is bad policymaking.

What we need in a military budget would be so much reduced if we used some of the money to address the kind of global threats that we have—the pandemic, climate change. I mean, how we have responded as a country and as a world to the pandemic is completely inadequate.

How we have dealt with public health is shocking. It’s been shocking to think about how under-prepared we have been from a public health standpoint for this pandemic, both through our own Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and also through support for the World Health Organization.

Mecklin: It is genuinely shocking. I want to go back to the new ICBM the United States is building. I know that your group has tried to lobby specifically against this. As your people go from office to office and try to raise this issue, can you just give our readers a sense of what the response is in Congress? In the community that the Bulletin deals with, there are a whole lot of people who go, “This is crazy,” right? Why are we building a brand-new ICBM that’s literally just a target?

Randall: I think anyone who’s a reader of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists or is connected to FCNL should understand that giving voice to their concern, their disappointment, their disapproval of further spending on nuclear weapons to their own members of Congress is essential. Members of Congress have to cover such a range of issues. Often they get elected because there is one issue or one motivating thing that drives them to run. Hopefully it’s for the welfare of the country. Sometimes it’s a little self-serving.

But they get elected not necessarily knowing the breadth of issues that they’re being asked to vote on or to consider. That is certainly true I think of all defense spending, but in particular of nuclear weapons. They’re just not expert. They are not experts in this. So having people’s voices come forward and say, “There is no reason why we should be investing $2 billion, $2.5 billion on the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent initiative this year, that is a waste of money. I ask that you do everything in your power to prevent it from happening.” In reality, it’s a pretty small set of people who get to make the first decision on this.

Once the first decision is made, it’s harder to stop. And the other reality is that the members of the House Armed Services Committee and the members of the Senate Armed Services Committee are people who often have parochial or district interests in these issues. Same for the energy committees that deal with nuclear weapons. But that doesn’t mean that other members can’t weigh in, and we are seeing some members of Congress who are questioning the assumptions for how we set priorities for expenditures in this country.

I think right now progressives and also in some cases libertarians are asking this question. One of our theories of change is that it’s really important to have civil conversations with elected officials and their offices, and to actually build a relationship with those offices so that the constituent is taken seriously. Most congressional offices aren’t expecting their constituents to call up and talk to them about nuclear weapons. So if someone is willing to do that and really stay with the office, it can have an impact. It won’t have an immediate effect, but it can have an impact over time.

Mecklin: Jerry Brown, who’s our executive chair, is constantly reminding us that nuclear issues just aren’t on the minds of most people in Congress. That’s something that they’re not concerned about because it’s not in the news of the day, it’s not the main thing. So I guess that theory of change—I mean, that’s part of what you’re lobbying effort is, is literally going congressional office to congressional office to try to create those connections. I guess I’m going to go back to the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent. When that’s raised in congressional offices, is there any willingness to listen at all? Or do they just go, “Pffft.”

Randall: Generally speaking, we are able to get meetings with most offices we ask to meet with, and we also focus our meetings. In the case of our lobbyists on the Hill, they are probably working most closely with the decision-makers that are specifically funding this. What we’ve heard: Part of what happens is that trade-offs happen. I can’t give you a specific example of like what’s traded for what else, but I think that sometimes there’s a willingness to say, “We’ll move forward with a certain system, but we’ll trade off funding a different [system]…” That’s my opinion. That’s not something stated directly. But I do believe that there is a momentum and a mythology built about what is “essential” and will be given a priority.

Former Defense Secretary William Perry, who’s been quite outspoken as you know about the question of, “Do you need to continue to have a land-based system at all as part of a triad?”—he’s not the only one, but he has an effective voice in raising this question. I have not seen or heard a willingness by congressional offices to really, in a serious way, question the whole strategic analysis of [a new land-based intercontinental missile].

Mecklin: My bottom-line question for you, getting to the end of this interview is: OK, let’s take the long view. Let’s say in a 10-year, 15-year view, what do you think needs to happen to set the stage for some president, some Congress being willing to make a cut, not even a massive cut, say 10 percent. That’s $75 billion a year. That’s a lot of money. What do you think needs to happen?

Randall: Well, a couple of things. One, I just talked about this from kind of a moral and political imagination viewpoint. I think we need leadership that is willing to re-imagine and re-engage a conversation about security. What does that term mean in this day and age, in 2021 or 2025? What does it mean to have national security? What does it mean to have global security and being able to name the security that we need?

I think this is changing because I do think we’re starting to see people recognize that having to be locked down because of a pandemic—there was nothing the military did to make that better, or prevent it. Addressing the global imperative of climate change: The military recognizes it, but they’re not doing much about it.

I think in particular rising generations understand this imperative for reducing Pentagon spending in a way that our generation and others may not. I mean, I think we recognize it, and I think there are people—scientists who have been the prophetic call on this—understand it. But there’s a certain lack of imagination on the part of elected officials to actually begin to think about how we can make transformative change.

Just coming back to the domestic side and what the Biden administration has proposed through the JOBS Act and the Families Act, that’s really generational change. Basically it’s really trying to reset how we prioritize expenditures through willingness to allow deficit spending and through restructuring some of the taxing of corporations and wealthy individuals.

I’ve often thought about guns versus butter. We’ve lobbied on that for a long time, that if you could reduce the Pentagon budget 10 percent, 20 percent, 50 percent, what would it free up for other expenditures? That’s an interesting question, whether or not there could be a way of understanding and addressing security that is not through the defense budget, but through addressing the need for vastly cutting our carbon emissions and for supporting other countries in cutting their carbon emissions.

We often come at such problems with a mind frame, particularly in our foreign policy, that we have to have enemies. Part of what we have to recognize is that while we certainly have vast differences with Iran or North Korea or even China, that’s probably not our greatest threat. Our greatest threat for humanity is more likely our extinction, whether it could be nuclear annihilation, or whether it’s climate change—I think this is a really forward-thinking way to look at it.

I think it’s going to be a generational change that will require people power—not just a few elected leaders. Because I don’t think it’s just the president; I think it’s going to be the kind of leadership that recognizes and has the power to make generational change. Whether Biden will succeed in this, around the domestic area [is one question]; he’s not going to do this to the military budget. That’s not his strength. He doesn’t see that, even though he sees that we have to address climate change. He’s not going to cut the military budget, I don’t think.

But whether it’s someone who comes after him … whether we see a Speaker of the House and a president of the Senate willing to start pushing their own caucuses in the United States to do this, I think it will be important.

I guess the one other thing I’ll just say is that those of us in Washington get really focused on Congress, and rightfully so; we should be focused on them. But there’s so much else happening in the world beyond. I mean, there’s leadership happening in other places that, sometimes, Congress has to follow, so to the extent that that leadership can push for the changes or would be willing to name the need to cut Pentagon spending as part of the way that leadership happens, that would be huge. If you think about industry beginning to at least give voice to addressing climate change. I don’t see any of them talking about the military spending. So there’s that.

I think the movements that are looking at investments are really compelling, as well. It’s a different form of advocacy—shareholder activism and the willingness of pension funds to stop investing in certain industries that are threatening—that’s another way that this kind of change can happen.

Mecklin: On that hopeful note—that a change in defense spending levels might actually happen sometime—maybe that’s a good place to wrap things up here. I really do appreciate you taking the time to talk. I guess really there is one final question: Do you think there’s going to come a time when most religious leaders actually come to care about defense spending, about spending all of this money on killing?

Randall: I do think that. I think religious leaders are also responsive to their religious followers. They recognize that there are people in their congregations who are connected to defense industries or military spending.

I had an interesting conversation with a Quaker once in Indiana when I was talking about militarism, and he said, “Well, we have people in our congregations who are in the military. So it’s hard for us to kind of be against that.” I said, “You don’t have to be against the people who are in the military, but you can be against the notion that militarism is the way that we’re addressing solutions in our world and that we are pouring billions of dollars into defense spending in ways that doesn’t benefit the military directly.’

FCNL’s vision is that we seek a world free of war and the threat of war. We seek a society with equity and justice for all, a community where every person’s potential may be fulfilled and an Earth restored. Those are Kingdom of God visions, if you will.

I believe there’s a call for those of us who are religious to look at what our religions claim, whether Christian or Jewish or Buddhist or Muslim, to look at what the religion, the fundamental essence of it is. We have the privilege honestly in Washington of working with other interfaith leaders who share many of these same goals. They haven’t prioritized military spending in the way that we have, but I think it will come. I do believe it will come.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.