“It’s a different kind of world we’re living in now”—Interview with political scientist Francis Fukuyama

By Dan Drollette Jr | November 9, 2022

“It’s a different kind of world we’re living in now”—Interview with political scientist Francis Fukuyama

By Dan Drollette Jr | November 9, 2022

In 1992, political scientist Francis Fukuyama published the tremendously popular and highly influential best-selling book, The End of History and the Last Man. At the risk of oversimplifying, it essentially argued that the struggle between ideologies was at an end, with the world settling on liberal democracy and the free market after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War. Now at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies at Stanford University, Fukuyama talked in this Zoom interview in mid-August with the Bulletin’s executive editor, Dan Drollette Jr., about how his thinking has evolved and changed since then—and in other ways, stayed somewhat the same regarding some premises.

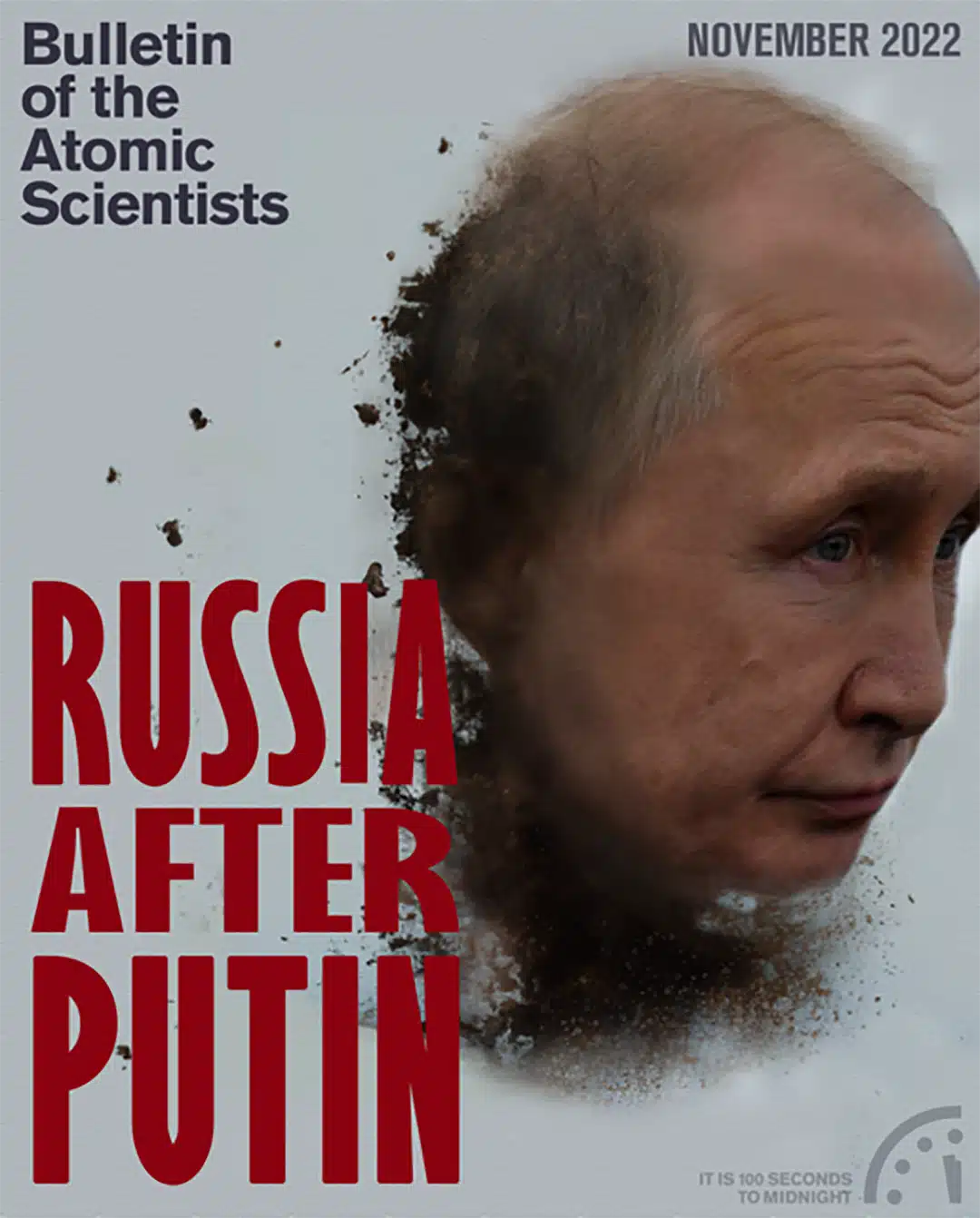

Fukuyama predicts that despite Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin, initially upending the trend towards liberal democracy, he will see more reverses. So far, Putin has seen none of his fondest dreams—Ukraine being overwhelmed by Russia, neutral countries distancing themselves from NATO, Eastern Europe becoming less democratic—come to fruition. But, says Fukuyama, other authoritarian so-called populists are continuing to emerge around the globe—including in the United States.

(Editor’s note: This interview has been condensed and edited for brevity and clarity.)

Dan Drollette Jr: As we approach the 30th anniversary of the publication of The End of History and the Last Man, I was hoping to find out what you think now, given current events in Russia and where things have been going in general since 1992. For the benefit of our readers born after the end of the Cold War, what would be the best way to sum up the central premise of The End of History?

Francis Fukuyama: First, we ought to define some terms. As I was using it, I meant “History” with a capital H—what you could today call modernization or development. And the “end of history” was not about a termination of historical events, but more about where that historical process was going.

So the premise was basically trying to raise the question of progress: You know, are we making progress in human civilization? And if so, in what direction is that movement tending?

And at that time, my argument was that for 150 years, most progressive intellectuals thought—along with Karl Marx—that at the end of history there would be some form of communism. Marx says that quite explicitly. My observation was that it sure didn’t look like we would ever get there, and that if we were tending towards any final outcome, it would look more like a liberal democracy connected to a market economy. That was the argument, anyway.

I didn’t see a superior form of social organization over the horizon that we were still aspiring to—but it didn’t mean that all existing political systems were great or perfect. That was the essence of the book, anyway.

Drollette: Has Putin’s invasion of Russia upended that argument? Or was it upended earlier, by 9/11 and the Iraq Wars?

Fukuyama: Well, you know, history never proceeds in a linear fashion; there’s a lot of ups and downs—as reflected in my subsequent big two-volume political order series.

In the 20th century, we had a very severe crisis of democracy, with the rise of Hitler and Stalin. And two World Wars. And a lot of other bumps along the road. Even as recently as the 1970s, democracies didn’t look so good.

So, the expectation is that not everything is going to be onwards and upwards every year. But, with a sufficiently long perspective, you can see progress in the way that human societies organize themselves.

That being said, if you take a short-term view, we’re clearly in a very different period right now than we were in 1992, when the book was published—which was just a few years after the fall of the Berlin Wall. At that point, we were about halfway through what the political scientist Samuel Huntington[1] called “the third wave of democratization,” where we went from maybe 35 democracies in the early 1970s to over 100 by the first decade of the 21st century.

But since about 2008, we’ve been in what’s been called a “democratic recession,” where things are going backwards and the number of democracies has fallen.

And I think more importantly, we’ve had some real setbacks to democracy in some big important countries, namely, the United States—but you know, India should probably be at the top of that list as well. We’re clearly regressing. There’s a lot of authoritarian governments on the move, and they’re consolidating power.

The Russian invasion is part of that regression. It has a special significance, because at least in Europe, at the end of the Cold War, there was a feeling that there was now a consensus about liberal democracy—and that the need for military conflict and territorial aggression had simply been superseded, because everybody accepted the post-1991 political settlement in Europe.

And that’s clearly not true now.

So in that smaller time scale, we have been going backwards. It’s a different kind of world we’re living in right now.

Drollette: I remember that there was a sense of optimism in the early 90s. It seemed that for a while everyone knew that the Russian word “glasnost” meant “openness,” and “perestroika” meant “restructuring.” But is it too much to say that the Cold War is now making a comeback?

Fukuyama: I’m not sure that’s the most helpful way to think about things; the Cold War had certain very specific characteristics, such as the conflict over ideology. But it’s certainly the case that the world is now being divided into countries that are basically liberal democracies and those that aren’t.

And the thing to keep in mind is that those non-democracies are very heterogeneous. Some of them are left-wing regimes like Venezuela or Nicaragua, while others are conservative nationalist ones, like Erdogan’s Turkey or Viktor Orban’s Hungary.

But what these authoritarians do have in common is what they don’t like—and what they don’t like are the rules that limit their own power. You see this going on in quite a few countries in a very disturbing way, all around the world right now.

Drollette: Would you put our ex-President Donald Trump in that category?

Fukuyama: Yes—he’s exhibit number one.

You know, what happens with the rise of a populist leader is that that leader is at first legitimately elected, just as Trump was in 2016. And he then goes on to use that democratic mandate to start dismantling the liberal part of liberal democracy—meaning, the rule of law or any constitutional constraints on executive power.

That’s really what Trump spent the next four years trying to do: trying to turn the Justice Department into a political tool that he could use rather than an independent enforcer of mutual laws. He tried to politicize the bureaucracy, and the federal judiciary more generally.

And I think the ultimate act of lawlessness was what happened on January 6—which, thanks to the January 6th Committee, we now know wasn’t just a spontaneous demonstration that somehow got out of hand. What happened that day was the result of a planned effort to overturn a legitimate election.

So yes, in fact, it’s very hard for me to think of another occasion in American history where a politician of that stature failed to accept an election outcome. In fact, it’s very hard to even think about other developed democracies where anything remotely like this has happened. So it is a very serious violation, I think, of liberal norms.

Drollette: But Joe Biden was elected—and has subsequently tried to restore some of those norms. Do you think those two things show that a Western democracy can be self-correcting?

Fukuyama: Well, it’s certainly better that we’ve got an electoral process that allows us to hold leaders accountable and replace them.

What I worry about right now is the fact that Trump has managed to convince a majority of the Republican Party that the 2020 election was illegitimate. That’s not a majority of the country, but it’s still maybe 30 or 40 percent of the electorate that thinks that Biden is not legitimately the president. And that’s extremely troubling from the standpoint of our democratic stability.

Not only that, but I think that in a way, Trump didn’t understand the mechanisms of American government well enough to actually overturn the 2020 election. But he and a lot of his colleagues in the Republican Party are now trying to put in place officials that agree with that “stolen election” narrative—as secretaries of state or people responsible for electoral administration. If those same conditions happen in 2024, they would, this time, be able to actually overturn an election successfully.

And that is going to provoke an utterly serious constitutional crisis. I think it’s actually one of the the most serious threats facing American democracy at the moment.

Drollette: So the first time was sort of a dry run—as if they were learning how to do it correctly? And now…

Fukuyama: … and now they’ve got the know-how, and they’re building the tools, yes.

Drollette: It’s a scary moment.

Fukuyama: Very scary. And what’s also very unfortunate is that most people—including those who don’t like Donald Trump—are not particularly aware of this problem, or mobilized around it.

That’s understandable to a certain extent, because it’s mainly political scientists—like me—who pay attention to things like the rules for vote counting, or the Electoral College, and so forth. Most ordinary voters are much more concerned about gasoline prices and those kinds of more immediate issues. And I think they tend to believe that our politics is still this normal kind of argument over taxes, regulation, so forth.

But I think much more fundamental issues are currently at stake.

Drollette: Can we change the trajectory of events? Didn’t you help to found a magazine with that mission?

Fukuyama: Yes, it’s called American Purpose.[2]

The magazine was really founded in order to defend a classical form of liberalism—the doctrine that all human beings have basic rights that need to be protected by a rule of law, and that that idea has been challenged by both the right and the left.

I think that ultimately, the way you protect liberal democracy is politically. By that, I mean that you have to win elections and put into power people who are committed to liberal democracy and to its institutions, who are willing to respect the norms required to keep a democracy running.

Ultimately, if you don’t win an election, you’re not going to succeed in doing that. And so, that’s been the focus of a lot of my efforts.

And I don’t mean the word “liberalism” in a partisan sense. I’ve never, in my lifetime, been a strong partisan where I really wanted to work for one particular party. In fact, I started out as a Republican and I switched parties. I felt that sometime over the last few years the Republican Party got more and more extreme—and there comes a point where if one party is slipping into what basically amounts to support for authoritarian ideas, then it’s no longer just a partisan issue; it’s an issue about the fundamental values of democracy. And I think that’s the point we’re at right now.

Drollette: Who are your presidential heroes? I read where you talked about something called “realistic Wilsonian-ism.”[3]

Fukuyama: I’m not sure that I’ve got presidential heroes that would be different from those who would be named by a lot of other people. I worked for George H.W. Bush—the elder Bush—who in many respects was one of the most competent presidents in terms of foreign policy. He was certainly in many ways one of the more far-sighted presidents: He successfully managed the end of the Cold War, which could have been an extremely dangerous moment in human history. And I think he did it very well.

And he did enable a big expansion of the number of liberal democracies in Europe, and tried to lay the basis for a post-Soviet security order in Russia.

Admittedly, Vladimir Putin is trying to undo that as we speak—but Bush actually had both the skills and the vision to at least start on the path leading to that kind of transition.

I respect leaders that have a similar internationalist view, that see the United States as not just another country but as an important linchpin in building a broader, stable global order. And if we don’t live up to those responsibilities, then the world is not going to be better.

Drollette: From reading the newspaper coverage at the time, I had the impression that the elder Bush really did try to reach out to allies and build coalitions; he didn’t believe in going it alone. And didn’t George H.W. Bush make some kind of a statement to the effect that when the Berlin Wall came down, he was not going to be dancing on the top of the wall? He was…

Fukuyama: He was very cautious; he didn’t want to rub it in the faces of the Soviet leadership that their side had lost the Cold War. The elder Bush was very conscious of the need for allies and for consensus. And in that respect, you know, he was quite different from his son, George W. Bush, who basically ignored the pretty universal opposition to the invasion of Iraq and simply went ahead. All of us are still paying the price for that, in many ways.

Drollette: Getting back to Putin—you were quoted in Salon back in mid-April[4] as saying that “He [Putin] looks like a great incompetent fool at the moment. His invasion of Ukraine has led to exactly the opposite result that he was intending. Putin has unified the Ukrainians. He’s cemented their idea that they are a separate nation with a strong national identity apart from Russia. Putin has wrecked the huge army that he’s built.” Is that correct?

Fukuyama: I think it’s even more true now than it was in April: Putin claimed to be worried about NATO expansion—and as a result of his invasion, Sweden and Finland are now both coming into NATO.

The one part that is not fully clear is what the outcome of the war is ultimately going to be. I continue to be relatively optimistic about what the Ukrainians are going to be able to achieve.

Because if you follow the actual events on the ground carefully, the Russian losses of manpower and equipment are absolutely stunning. As of today [August 11], the Pentagon is estimating that they’ve lost 70,000 to 80,000 killed and wounded in the first six months

That means that Russia has lost maybe half of the invasion force that they had amassed around Ukraine. It really quite unbelievable. In terms of logistics, they are scraping the bottom of the barrel in terms of manpower, because they can’t get enough of their own people to fight for them.

If these trends continue, it’s entirely possible that the Ukrainians will be able to push them out of at least the south of Ukraine, and reopen their Black Sea coastline—which I think is very crucial to Ukraine’s survival as an independent nation. Ukraine is one of the world’s biggest agricultural exporters, and this global food crisis that the global south is in the midst of is largely due to the Russian blockade of those Black Sea ports. It’s very important that they be reopened—both for Ukraine’s sake and for the sake of all the people that need to buy that grain.

And I do think that there’s a possibility that will happen by the end of this calendar year.

Drollette: Do you get the impression that the goalposts keep moving, when it comes to people’s expectations for Ukraine? It seemed that in the beginning, the experts were saying, “If Ukraine can hold out for three days, that will be a major victory. Then it was “If they don’t lose their capital, then that’s a success.” And now it’s “Can the Ukrainians push the Russians out entirely?”

Fukuyama: Yes, definitely.

And at the same time, people have underestimated the Ukrainians from day one. Within the US intelligence community, all the pundits were expecting that Russia could defeat Ukraine very quickly. When that didn’t happen, they then started saying, “Well, it’s inevitable that there’s going to be a slugfest and a long war of attrition, and Ukraine will not be able to keep the Russians from making incremental gains.”

But I don’t think that conventional wisdom is really wisdom at this point. We still may be under-estimating the Ukrainians. We’ll have to see, but I am reasonably hopeful that momentum is going to shift—and could shift fairly dramatically to the Ukrainian side. And that’s the only basis on which it makes sense, I think, to open up some kind of a peace negotiation.

Drollette: What preconditions need to be in place for both sides to want to come to the bargaining table?

Fukuyama: Well, I think that the Russians have to be weakened to the point where they are hurting, and they realize that they’re not in a position to expect a sustainable, long-term occupation of the land they’ve conquered. That could happen either militarily—by simply being driven out—or it could come about by sheer exhaustion and their realization that they can’t sustain that army in the field.

At that point, they may be worried about a broader regime collapse, and that might prepare them for going to the negotiating table.

Drollette: And on the Ukraine side, do they need some more victories?

Fukuyama: Yes, I think so.

This all goes back to the fundamental analysis of why this war happened in the first place. There is a view out there that’s been pushed by John Mearsheimer[5] at the University of Chicago, who says that Russia was driven to this invasion by NATO expansion, that the steady expansion of NATO after 1991 led to security fears on Russia’s part, and this is simply their reaction to it.

Now, John happens to be an old friend of mine. But on this point, I disagree with him completely, for several reasons.

First of all, if you simply listen to what the Russians have been saying about their motives, then of course they didn’t like NATO expansion—but then again, they didn’t like any of the changes that happened after the collapse of the former Soviet Union: They didn’t like Ukraine becoming a separate country. They didn’t like the Warsaw Pact dissolving. They didn’t like Eastern Europe becoming democratic. And they pretty much stated explicitly that they’d like to reverse all of those things.

So I think that any kind of a short-term ceasefire or peace negotiation right now, when they are occupying a quarter of the territory of Ukraine, is not going to bring peace. It’s simply going to be a ceasefire. The Russians will rearm, and the moment they feel strong enough to start the war again, it’ll start again.

Consequently, I think that the Russian have got to be put into a position where they realize they can’t pursue that strategy. And that requires them to be pushed out of a lot of the territories they’re in right now, and feel a lot weaker. At that point, I think you might be able to have a serious negotiation.

Drollette: In American Purpose, you wrote an op-ed called “Preparing for Defeat,” that argued that Russia could outright lose in Ukraine—and that the collapse could be sudden.[6]

Fukuyama: Yes. Obviously, it didn’t happen last spring—although the Russians were defeated in the north and had to withdraw from the area around Ukraine’s capital of Kyiv, and around Kharkiv, and then move back to small sectors in the east.

And there are still important sets of battles that have yet to happen.

But I do think it is possible that their broader position will start to completely collapse, because their manpower and equipment losses have been absolutely stunning. And now they’re finding that Crimea itself is vulnerable. They’re losing what they thought was a secure rear area.

Drollette: And speaking of vulnerable, it was shocking to see that the flagship of the Russian fleet, the Moskva, was sunk. Do you think there is any danger that at points like that—when there is such a shocking loss to Russian pride—that Putin says to himself “I’ll show them: I’m going to make a demonstration, I’m going to launch a nuclear missile?”

Fukuyama: The propensity to escalate is a serious question.

And it’s not just nuclear—there are also chemical and biological weapons that the Russians have in their inventories.

I think that anyone that dismisses those fears out of hand is not thinking right, because this is one of the biggest nuclear powers in the world that you’re dealing with.

I do think, however, that the likelihood that they will simply lash out in that fashion is not as high as a lot of people think, for a couple of reasons. The most basic one just has to do with the nature of nuclear weapons, period. They’re really not good as military weapons—things that are useful for conquering countries by seizing and holding territory, that sort of thing. The primary use of nuclear weapons is deterrence—to prevent the other side from using their nuclear weapons.

And the Russians know that, and they know that any first use of nuclear weapons is going to be met by retaliation—either nuclear or with conventional forces—and that all of those scenarios make Russia worse off than it would have been if they had not escalated.

So as long as you’ve got a rational leadership there in Russia, I think that’s going to hold.

The second reason I think they won’t lash out in that way is that throughout the war, they actually haven’t given any indication that they’re preparing to escalate in this fashion. I mean, if they wanted to do this, you’d see all sorts of indicators, such as the Russians starting to take these weapons out of storage, move to higher levels of alert, and so forth. And none of that’s happened, not even after the sinking of the Moskva.

I mean, while many thresholds have been crossed, the Russians have actually remained quite, quite cautious.

So I don’t think that they’re these trigger-happy people.

That being said, I think that the Biden administration has been appropriately cautious. Right from the beginning, they said that they were not going to try to impose a no-fly zone over Ukraine, because a no-fly zone would require attacking Russian targets, both in the air and at bases in Russia. And I think there is a real fear that once you cross that threshold—where the US or NATO directly attacks Russian target—that that will require some kind of a Russian response. And so that’s why the United States has held back on that sort of escalation.

Drollette: Do you see a way in which Putin can survive this mis-adventure in Ukraine?

Fukuyama: Unfortunately, these authoritarian regimes are pretty resilient. Look at Assad in Syria, or Nicolas Maduro in Venezuela—these are leaders who, over the course of a decade, have completely wrecked their country. Syria and Venezuela are neck and neck for setting world records on the number of refugees—they produced over 4 million in each case—people just being driven out of their countries. Yet these dictators are still in power.

So I don’t think that there’s any kind of automatic level of failure that will force Putin out, though there’s a lot of speculation. Certainly, if you are a Russian elite, or in the security services, and you can see how you’re getting whipped by Ukraine—which you thought was going to be a cakewalk—then you would be pretty upset.

But in politics it’s very hard to know when that unease translates into actually being willing to take action, because that’s so very risky. And there’s lots of feelings of nationalism and national pride and so forth involved. So I wouldn’t make any predictions about Putin’s survival, except to say that we can’t count on his being brought down by anything that happens on the battlefield.

Drollette: I can’t even think of who would be his possible successor.

Fukuyama: One of the problems with Russia is that it’s what we political scientists call a “personalistic regime”—meaning it’s not built around strong institutions where you have a clear, constitutional line of succession. I mean, they do have a constitution and a theoretical line of succession, but in real terms, if Putin were to die of a heart attack tomorrow, there would be a mad scramble for power among all these powerful oligarchs and heads of security services and military people. There just isn’t going to be an orderly way to oversee that.

Endnotes

[1] See review by Scott London of Samuel P. Huntington’s book, The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century https://scott.london/reviews/huntington.html

[2] See https://www.americanpurpose.com

[3] See “After Neoconservatism,” op-ed by Francis Fukuyama, New York Times, February 19, 2006. https://www.nytimes.com/2006/02/19/magazine/after-neoconservatism.html

[4] See “Francis Fukuyama on Putin, Trump, and why Ukraine is key to saving liberal democracy,” by Chauncy Devega, Salon, April 18, 2022. https://www.salon.com/2022/04/18/francis-fukuyama-on-putin-and-why-ukraine-is-key-to-saving-liberal-democracy/

[5] See “Why the West is principally responsible for the Ukrainian crisis” by John Mearsheimer, The Economist, March 19, 2022. https://www.economist.com/by-invitation/2022/03/11/john-mearsheimer-on-why-the-west-is-principally-responsible-for-the-ukrainian-crisis

[6] See “Preparing for Defeat,” by Francis Fukuyama, American Purpose, March 10, 2022. https://www.americanpurpose.com/blog/fukuyama/preparing-for-defeat/

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: 2024 election, Cold War, Francis Fukuyama, Putin, Russia, Ukraine, liberalism, neo-conservativism, the end of history

Topics: Special Topics

There is not one u.s. president in anyones memory that could be described as “forward thinking.” Meddling would be far more accurate a description for Bush I.

Calling the u.s. a linchpin for democracy? They have overthrown more democracies than the next 5 dictatorships over the past 50 years.

And if Trump’s stable genius qualifies as your exhibit A, then just how fragile are your liberal democracies?

Please, Fukuyama, put the washington koolaid down.

Do you really think Klaus Schwab will be giving up steak and lobster while he tries to reset the rest of us into eating bugs?

If so I have a bridge for sale