Interview with Susan Solomon: The healing of the ozone hole, and what else we can learn from atmospheric near-misses

By Dan Drollette Jr | May 9, 2023

Interview with Susan Solomon: The healing of the ozone hole, and what else we can learn from atmospheric near-misses

By Dan Drollette Jr | May 9, 2023

Perhaps the best example of successfully managing a climate change “near-miss” is the 1989 Montreal Protocol that banned chlorofluorocarbons—which demonstrates the power of science and international cooperation to resolve a common environmental problem.

A UN report released in January 2023 reported that the ozone layer is healing so quickly that it will be fully restored within a few decades—an astounding finding, considering how dire things had looked not that long ago. The fact is that the Montreal Protocol (designed to rein in the chlorofluorocarbons responsible for causing the ozone hole) did more to reduce the warming of the planet than many observers expected; the reason being that the chlorofluorocarbons themselves turned out to be not just ozone-depletors but also very potent greenhouse gases.

So, solving a problem in one area had unexpected, beneficial, knock-on effects in other areas.

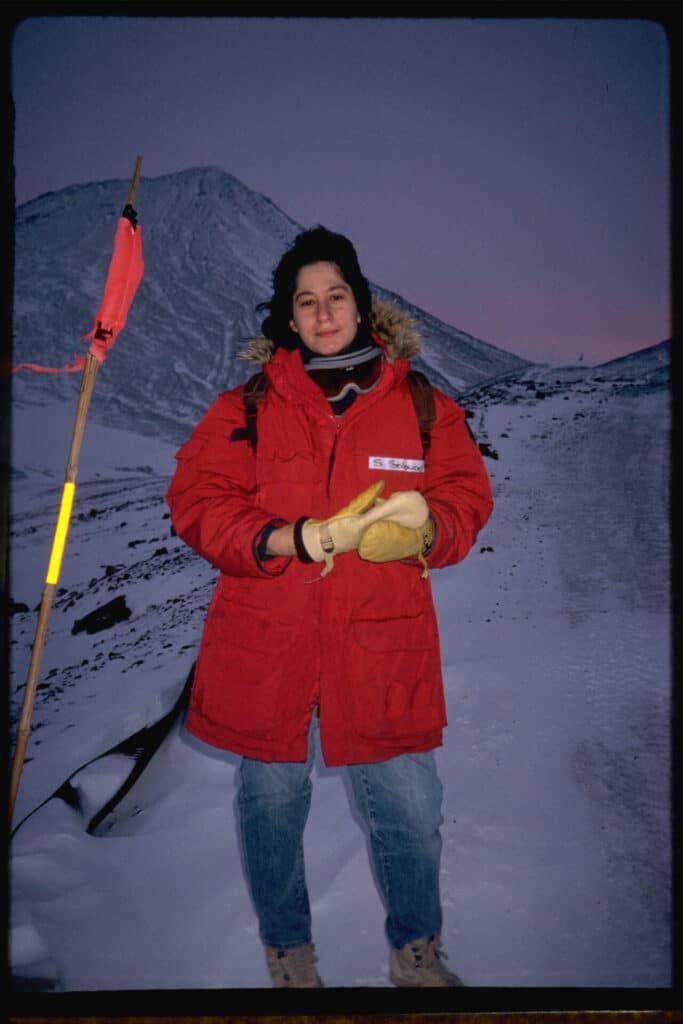

Such happy results are not limited to just this one situation, says Susan Solomon, noted ozone researcher and Martin Professor of Environmental Studies at MIT. (In 1986, Solomon led a scientific expedition to Antarctica, to get real-world data and study first-hand the chemistry involved in the process of ozone destruction. Her studies identified the mechanism for ozone destruction.)

There have also been major improvements in a number of atmospheric environmental problem areas, such as air and water quality, smog, leaded gasoline, and herbicides. What all these stories of success—or if not 100 percent success, then enormous improvement—seem to have in common is what she calls the “Three Ps.” Each problem felt Personal, was readily Perceptible, and could be dealt with via Practical solutions.

In this interview with the Bulletin’s Dan Drollette Jr., Solomon elaborates on these ideas. And she explains why it’s important to make people aware of these promising outcomes, and celebrate them—while being sure to keep the pressure on those in charge to see the solutions through to the end.

(Editor’s note: This interview has been condensed and edited for brevity and clarity.)

Dan Drollette: When we think of close calls, we tend to think of all those times that the Air Force accidentally dropped a bomb, or can’t locate one. But it seems like there are other kinds of near-misses, such as what happened with the hole in the ozone layer. Maybe we could learn something from the experience with the ozone layer when it comes to dealing with climate change as a whole. I understand you’re actually writing a book right now along these lines?

Susan Solomon: Yes, but it’s not just dealing with the ozone hole. It also deals with a whole series of near-misses that ended up being amazing success stories, all related to atmospheric chemistry and physics.

For example, one of them is smog. If you think back to the way things were in Los Angeles in the ‘60s and ‘70s, we did a pretty decent job of cleaning up the air. That’s not to say that we don’t have any air pollution now, but we have way less.

And another example would be leaded gasoline. If we had kept using leaded gasoline the way we were, the number of damaged children surely would have continued to go up rapidly.

I don’t have numbers that I can quote offhand, but the average amount of lead in the blood of young children has gone down dramatically over the past 30-odd years, and there’s very good data on that. In fact, it was the blood lead levels of children that convinced people to get rid of leaded gasoline. [Editor’s note: The median concentration of lead in the blood of children between the ages of one- and five- years old dropped by 96 percent from 1976 to 2018, according to the EPA—with the greatest decline occurring after the elimination of leaded gasoline.]

Drollette: So, getting down to the nitty-gritty, when people ask you “What was the problem with the ozone layer” and “What did the Montreal Protocol do to fix it”—what do you tell them? Because a lot of people who read the Bulletin were born well after the hole in the ozone layer was front-page news.

Solomon: The reason I’m writing the book is exactly because of that demographic—and that demographic has grown up in an era in which almost all we’ve had is environmental frustration.

But that’s not how it has to be, and I think I can point to some real success stories; the Montreal Protocol being one.

First, to backtrack a little bit: In 1974, two scientists from the University of California-Irvine published a paper saying that if we continued to use chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) at the rates we were using them, then we would see a few percent change in the ozone layer in 100 years. At first glance, a few percent in a century sort of sounds a lot like the way we used to talk about climate change, right?

But that finding was enough to spark major public interest, which in turn was enough to make people move away from spray cans that used CFCs as a propellent—things like underarm deodorant and hairspray.

And that actually destroyed the market for the American manufacturer.

Which led industry to become motivated to look for substitutes, and for governments to sign treaties —like the Montreal Protocol—to cut down on the amount of CFCs emitted into the atmosphere, because these chemicals were combining with stratospheric ozone to form what was essentially a hole. And industry and government were very successful in accomplishing that.

But I think the fundamental thing to celebrate here is that citizens actually made a choice to do something good for the environment, which ultimately led to solving what would have been a major environmental problem.

And it’s worth noting that this drive happened in the United States and a few other countries; it did not happen in most of Europe.

So the long and short of it is that after we thought there was only going to be a few percent change in 100 years, all of a sudden, boom, we get this ozone hole over the Antarctic, which nobody predicted, and we realized we had to up our game, and do more than just ban deodorants that used CFCs. We had to go after everything—refrigerants, the propellants used to blow bubbles in spray foam insulation, every kind of thing you can imagine.

The immensity of the ozone problem was first measured by the British Antarctic Survey. And what they found is that we had lost something like half the ozone already, and we were barely only into the 1980s—decades in advance of what was expected to happen a century away.

Drollette: I guess that goes to show that you can’t always assume that the most conservative forecasts will be the ones that turn out to be true.

Solomon: Right. This finding was way outside all the predictions, happening much faster, and way worse. It certainly had a large role to play in getting many countries on board, because people viewed Antarctica as the canary in the coal mine. And they realized that if we didn’t do something, then we were going to have massive losses of ozone all around the world. At the rate we were going, by the year 2050 there pretty much would have been an ozone hole everywhere over the whole planet.

It would have been just one giant doughnut hole—with no doughnut.

Drollette: This might be obvious, but why do we need ozone?

Solomon: The reason we need ozone is important to mention. It absorbs certain kinds of ultraviolet light that are disastrous for biological systems. If you’ve ever been sunburned, you know it hurts. And you probably know that if you got sunburned too many times you run a real risk of skin cancer. The other thing that happens to human beings, by the way, is cataracts from ultraviolet light. And that’s just what’s happening to human beings.

But imagine all the things that are probably risks to animals and plants, and everything else in the entire ecosystem.

Life on the surface of our planet was only able to come out of the sea and walk around on land because the ozone layer evolved to allow for the development of all life, not just human life. All life on Earth was intimately tied to the ozone layer’s evolution.

Drollette: So, how successful was the effort to protect the ozone layer?

Solomon: In the time since the Montreal Protocol— a binding agreement to phase out ozone-depleting substances, particularly chlorofluorocarbons—was put together, the emissions of CFCs and related substances have dropped more than 99 percent.

What’s left are in things like old refrigerators, and in the walls of old buildings that had insulation in the form of blown-in fluorocarbons—because they’re really good at making foam.

That stuff is still in fridges and walls, and slowly leaking out. And whenever you tear down the building, a lot of it will leak out into the atmosphere.

Nobody is making CFCs anymore. And that’s true worldwide, including countries like China and India, which had been given a grace period because of their situation as lower-income countries.

They were allowed to continue to make it much longer, which made sense because they were emitting almost nothing in the beginning. That’s fair.

We in the States were phasing out CFCs in spray cans even before it was clear that they were going to cause this big ozone hole. But the phase-out in refrigeration and air conditioning, of course, was much later because that was more difficult to substitute with other things.

But ultimately, it wasn’t that hard. Alternatives were found—and there were just so few companies that were making CFCs, maybe 15 companies worldwide.

Drollette: Could the same thing be said of the current problem with carbon emissions? We once ran an article in the Bulletin about a researcher who found that just 90 companies are responsible for more than 60 percent of greenhouse gases.

Solomon: That sounds right to me. Although we all consume fossil fuels, the number of those who actually make it is fairly limited.

So you know, I’m not sure the situation is all that different.

But I will tell you what really is a major difference: In the case of chlorofluorocarbons, it was always clear that the chemical companies were going to be the primary ones to make whatever came next to replace CFCs—after all, that’s their business. And they love making new chemicals. Admittedly, sometimes they get overly enamored of something that’s a big seller that they don’t want to give up, like [the herbicide] Round Up in the case of Monsanto—but the point is that in general, I think the willingness to change is much stronger in technology-oriented companies like that. This is especially true when the products in question aren’t making them a fortune—and let’s face it, CFCs were only 2 percent of DuPont’s business, even at their height. (This is not to say that the chemical companies were perfect; the CFC-makers also had their issues.)

But when it comes to the fossil fuel companies, they have massive investments in the existing infrastructure. And they have massive investments in mineral resources—if you’re a coal company that owns a mountaintop full of coal, then it’s worth a lot of money to that company to keep being able to mine that coal; they’re certainly not the ones who are going to build solar panels.

So there’s a very, very different economic dynamic for those companies.

That said, I think you have to give a number of these companies some credit, though, because if they do actually put their actions where their promises are, then they will be genuinely taking steps forward.

There’s quite a few good companies that see the need to move out of that business and do things like make hydrogen, which may be able to help solve the greenhouse gas problem. And at least some of them did move over to methane gas, which did help tremendously in phasing out coal—and coal is much worse, because it produces about twice as much carbon dioxide for every unit of energy as gas does. So, that is a real step forwards.

Fundamentally, job one is to phase out coal. If we were to burn all the world’s coal, the planet has been estimated to warm by more than 10 degrees Celsius (18 degrees Fahrenheit). That would indeed be a climate catastrophe.

Drollette: That raises something I wanted to ask you about. In an interview with Technology Review you talked about the three P’s to solving environmental challenges?

Solomon: I think there are three items, all beginning with the letter “P,” that seem fundamental to society doing a good job on an environmental problem: Personal, Perceptible, and Practical.

The first is that the issue feels Personal to you. I think it’s not good enough for it to feel personal in terms of your grandchildren. You know, we’re all pretty selfish, it’s really all about us. So, you know, if we’re going to get skin cancer, that’s a scary prospect. And that was the risk that the ozone hole posed to us.

The second P is that it needs to be Perceptible. In other words, we either need to be able to see the problem ourselves, or at least understand the problem. In the case of smog, for example, it was both heavily personal—people were getting asthma, and they couldn’t breathe—and incredibly perceptible. In the case of ozone, it’s pretty perceptible: Not only do you get sunburned, but the satellite images of the ozone hole over Antarctica are easy to understand. The science could be readily communicated. You didn’t have to be a statistician to realize there was a hole there.

And the last one is Practical. You need to be able to believe that there are practical solutions.

In the case of the ozone problem, there were lots of options for things to replace CFCs as a propellant. The spray cans were replaced with essentially no visible change to the consumer. It was literally used largely for underarm deodorant, for example, and it was pretty easy to replace the deodorant with roll-ons or sticks. And the advertising for this was pretty straightforward: Get on the stick to save the ozone layer.

I think most people are willing to do things that aren’t too hard, if they understand why it would be helpful to the environment. And certainly, the other thing that the deodorant companies did masterfully—particularly Johnson and Johnson—was to start talking about the fact that you actually get more days’ worth of deodorant from a roll-on. Very practical.

So there you have it: the three P’s.

Drollette: Though I guess the problem is that sometimes things are not perceptible immediately, or not personal, or not seen as practical. I’m thinking that if you live in the South Pacific on a low-lying island and your house is sinking under the waves, then it’s pretty obvious to you that the sea levels are rising. But it’s not as immediately perceptible on the other side of the globe, or inland, or at high elevations.

Solomon: I think one of the blessings of the internet is that we now have a much broader knowledge of climate and weather events in other countries, along with pictures of it. And the data shows that in the past 10 years, there’s been a tremendous increase in the percentage of Americans—in every state in the union—who think that the climate is changing, and that it’s a real risk that’s bad for people and for the world.

That’s a huge change from before. It’s fantastic.

And the majority of those people are also in favor of research into renewable energy and doing things to fight climate change. So I see people taking it more personally, in part because of their own experience of heavy rainfall, increased hurricanes, and more extreme conditions.

And with more exposure to international climate events, people are beginning to realize how other people around the world are really suffering.

You have to understand that 20 years ago, when people would interview me about climate change, I would say: “Just wait, it’s going to become perceptible.” And I believe it really has become much more apparent—particularly on the hottest summer days in most places in the world. It’s just amazing.

Drollette: From reading the literature, I get the impression that there are a lot more practical solutions around these days—a lot more affordable renewable technologies. The price of solar panels has just really dropped like a stone.

Solomon: This is absolutely true. On the practical side, you may still hear the occasional person saying, “We can’t afford to change anything.” But there are a lot of energy companies now building solar power plants instead of using coal, which is getting quite expensive to operate. Solar is cheaper than coal and cheaper than gas now, and so is onshore wind. Offshore wind is a little more expensive, but onshore wind is comparable to solar, in terms of price.

And the other great development that has occurred is the emergence of what they call “small community solar.” In other words, you, the consumer, don’t have to deal with a mammoth energy company anymore. So community solar is becoming a big thing, particularly in rural areas. And who doesn’t want to be liberated from a big monopoly?

Drollette: Any last comments?

Solomon: In regards to climate change, realistically speaking, we’re not going to go live in caves and wear bearskins—and no one’s asking us to. We need the modern energy lifestyle in order to not only be comfortable but also healthy and safe. We aren’t going to devolve. And that means our only choice is to decarbonize the energy supply.

And to make decarbonizing happen, don’t sit back and wait for the politicians to do it for you. It’s not going to happen that way. It will only happen if the public demands it and supports it.

I think that now there is enough public support for renewables for them to happen, certainly in Europe—and we’re starting to catch up here in the States. I mean, the Inflation Reduction Act was a masterstroke; it’s going to cause some major changes in our ability to access clean energy.

So there are lots of reasons why I think that a new day is dawning, and why we should be optimistic.

Let me give you an example. When the public demanded it, the Clean Air Act was passed, because of the overwhelming public support for change. And it happened on Richard Nixon’s watch, of all things—who also created the Environmental Protection Agency.

In fact, here’s how important it is to demonstrate and show politicians what you think. Nixon was looking out the window of the White House on the first Earth Day, when he saw the crowd streaming down to the National Mall. According to the memoirs of those who were with him in the room—Ehrlichman or Haldeman, I forget which—he turned to his aide and said: “I need to be a player in this.” So, because public opinion was so strong—20 million people turned out for the first Earth Day—we later got the Clean Air Act, and the EPA.

Now, I’m sure the creation of these things was brewing in the back of his mind for some time; Nixon was probably already looking for ways to do something in this area, because he closely studied public opinion. But certainly, that was the day that Nixon decided he really had to kick it off.

It was done under the rubric of “streamlining of government,” which involved other agencies as well, and which was kind of already underway. But I’m pretty sure he announced that he would form an EPA just a few days after Earth Day.

That first Earth Day was in April 1970. And the EPA was created at the beginning of December 1970. That was pretty fast, considering the magnitude of what happened.

Drollette: I never would have associated Richard Nixon with anything that could remotely be considered environmentally friendly or progressive.

Solomon: At the end of the day, Nixon was a politician—and as a politician he understood that “If I want to succeed, this is what will get me elected.”

So I guess that if there were to be a moral to the story here, it’s that things do not always proceed in a straightforward, linear, or predictable way.

And if I could add another moral to the story, it is that success is not guaranteed. People have to keep banging the drum.

But we do have things like the Montreal Protocol to look at, as a case of a near-miss that was successfully avoided. The same is true with what happened with smog, with leaded gasoline and with lead paint—there were so many hazards that we successfully avoided, so many near-misses that hopefully we’ve learned from.

Change can happen when the public demands change, even when you’re talking about a big industry like the auto industry—which realized that it had to suddenly start making cars that didn’t need leaded gasoline. That was a very big change for them. But they did it.

Drollette: What’s the title of your book, and when do you expect it to be out?

Solomon: It’s called Solvable. It’s from University of Chicago Press. I wish it could be faster but I’m excited for it to be out in about a year.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: 2024 election, Clean Air Act, EPA, Montreal Protocol, chlorofluorocarbons, climate change, climate crisis, global warming, lead, ozone hole, smog

Topics: Climate Change, Interviews