The explosive musical score to Oppenheimer

By Reba A. Wissner | July 26, 2023

The explosive musical score to Oppenheimer

By Reba A. Wissner | July 26, 2023

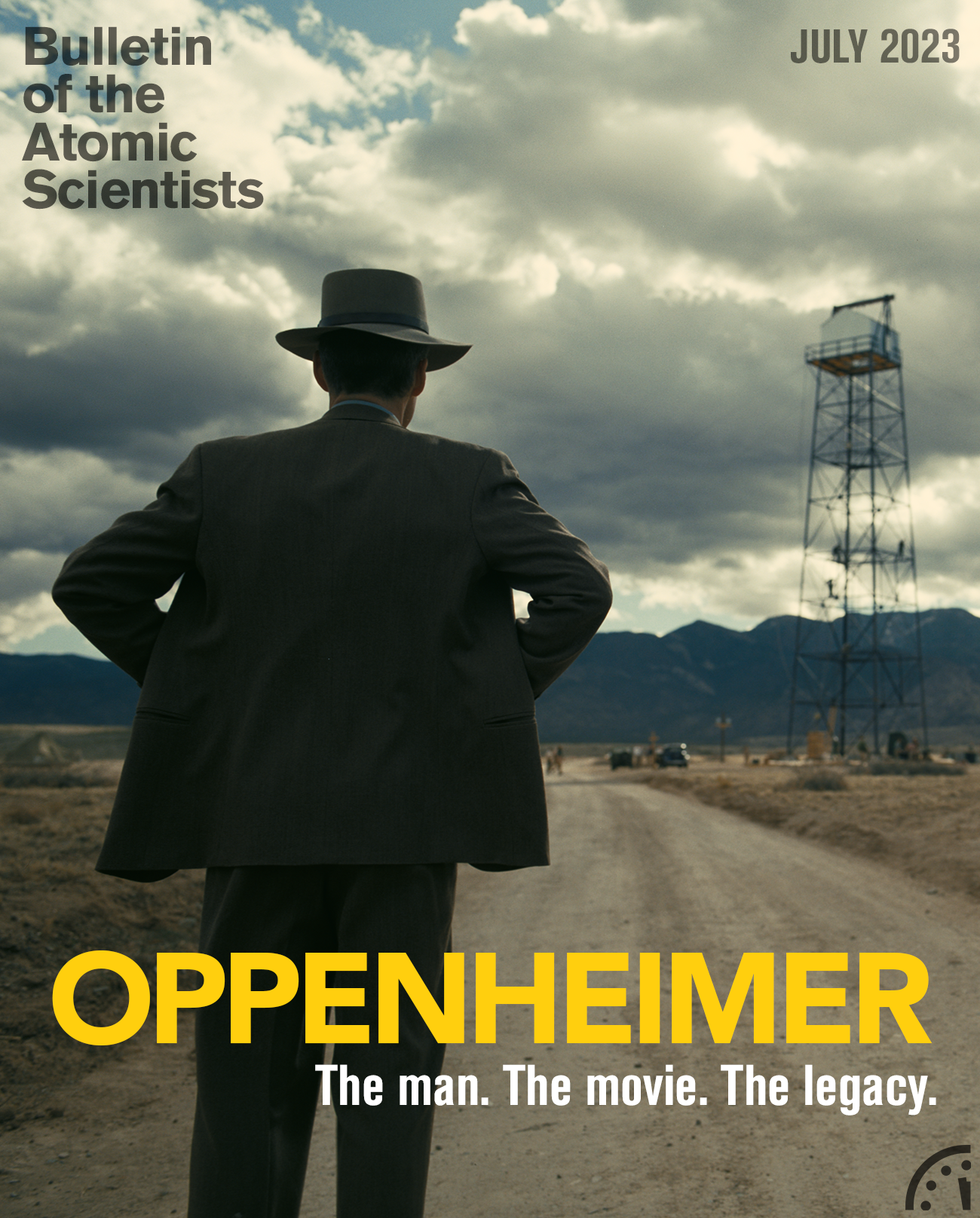

Robert Oppenheimer’s name has been everywhere lately, with good reason: The eponymous film has been long-awaited since Christopher Nolan first announced he was directing a biopic on the theoretical physicist. The Oppenheimer name has become a social media hashtag, both on its own and as a portmanteau with Barbie’s name (Barbenheimer) because both films premiered the same day. There have even been song playlists dedicated to both films.

Pop-cultural buzz aside, the film—based on Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin’s book American Prometheus: The Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer—is an engaging and mostly accurate depiction of Oppenheimer’s life, covering his early studies in Europe and professorship at the University of California-Berkeley, bouncing back and forth between his life at Los Alamos and the invention of “the gadget”—as the first atomic bomb was called—and his security clearance hearing in the 1950s. It spends a lot of time drawing on Oppenheimer’s ties to known communists as a reason for difficulties obtaining his security clearance at Los Alamos and for the revocation of his security clearance afterward.

As a music historian who has studied how composers depict nuclear testing and anxiety in film and television, I’d be remiss to not mention the dynamic nature of Ludwig Göransson’s score, which he recorded in five days. The score is integral to the film and its narrative, which contains almost wall-to-wall music; the composer estimates that roughly 2.5 of its 3 hours features music.

That’s over 83 percent of the film, though it honestly felt like more. Göransson’s scoring stemmed from Christopher Nolan’s suggestion that the violin form the basis of the score, and the instrument was present throughout almost the entire film.

The violin was used to great effect here, especially through the use of quick slides up the fingerboard and dissonant violin screeches (think of the shower scene in Psycho) that create an uneasy effect. The two-note descending patterns of the violin after the scientists hear about bombing of Japan also channels the opening of the “Lacrimosa” movement from Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s Requiem (a mass for the dead), the lyrics of which translate to:

“Mournful that day

When from the ashes shall rise

a guilty man to be judged.

Lord, have mercy on him.

Gentle Lord Jesus,

grant them eternal rest.

Amen.”

This is a clear commentary on the bombings of Japan and Oppenheimer’s role in them. One of the unsung heroes of the orchestra in the score is the harp, which makes its appearance during some of the most tense moments in the film, and this repetition signifies being stuck in a situation from which one cannot be easily removed. The music consistently alternated between suspenseful to hummable—helping to create emotional contrasts driven by the film.

Göransson’s score was clever in ways that could easily go unnoticed. For instance, several of the cues were grounded in the use of triplets (the playing of three notes in the time that two notes should be played in the music), which is a clear allusion to the Trinity test’s obvious reference to the number three. Music pervaded the film, making the passages in which there is no music obvious in their striking silence—and how that silence represents the gravity of the situation, especially in the first moments after the gadget being detonated.

The gradually increased volume in some of the film’s tensest scenes—such as the one in which Oppenheimer is questioned at his hearing about his moral compass—correspond to the emotion being exhibited by the actors. The volume card was overplayed at time, with the music too loud in some places, drowning out the dialogue (a common problem in Nolan’s films). Still, the sound mixing for the film was generally done to good effect.

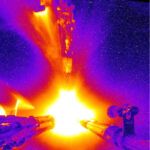

Several other aspects of how music and sound were handled immediately jumped out at me. First, the powerful Trinity Test scene reminded me of other treatments of nuclear detonations on film and in television. Once the gadget was detonated, it took what felt like several minutes to hear the explosion—but was actually a matter of seconds. We saw the explosion’s catastrophic effects and the reactions of the scientists, including Oppenheimer, but by the time we heard it, it almost felt like we forgot it would make a sound. This delay of sound in favor of focusing on the fireball’s image was a common tactic in earlier depictions of nuclear detonations in film and television. For instance, you can see and hear this approach in a 1949 episode of the TV series Suspense called “Nightmare at Ground Zero,” though not with so long a pause as in Oppenheimer. Göransson also used the synthesizer as part of the score, which was a common feature in nuclear-themed film and television episodes as early as the 1960s.

(Incidentally, high-energy particle physicists such as Virginia Tech’s Kevin Pitts—formerly chief research officer at Fermilab—said in a press release that while the delay between the flash of light and the sound of the explosion may first appear as purely an artistic choice done for effect, the opposite is true: “In fact, it was technically very accurate—While the light from the explosion would have been visible immediately, it would have taken about 30 seconds for any sound, and the associated shock wave, to arrive.”)

I take issue with one aspect of the film: It humanizes Oppenheimer as a tortured genius whose moral compass forced him to reckon with the outcome of his invention. However, as many people have already commented on social media, Nolan’s treatment of the victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki made them into faceless beings.

They are referred to only twice in the film. The first instance is when Oppenheimer speaks to the people of Los Alamos about the bombings. We see what he sees as his mind plays tricks on him: the flash of light followed by a woman whose skin is peeling off (we also see this image again later in the film). We also hear what sounds like bombing in the background of his speech as the background behind him shakes before these illusions plague him. As he leaves the building, he sees a pile of black ash in what may be the reference to an incinerated body. After he exits a building, another Los Alamos scientist is vomiting into a garbage can; it is unclear whether he is doing so is from the news, or if he is drunk from celebrating, or if it is another one of Oppenheimer’s illusions.

The second instance comes when the scientists are being briefed about the outcome of the attacks. We hear a voiceover of the person running the slides about the damage and death that resulted, but we never see any images. Now, I am not suggesting that graphic images from Hiroshima and Nagasaki should’ve been shown in the film. What I am saying here is that these two scenes dehumanize the victims of the atomic bombings, even as Nolan goes to great lengths to humanize Oppenheimer.

Despite my familiarity with the Manhattan Project, the film’s story and music left me with a lot to consider. In the last scene of the film, Oppenheimer talks to Albert Einstein and reckons that the unleashing of nuclear weapons created a chain reaction that changed the world. Indeed, it has.

While a piece of entertainment, the film has brought awareness to nuclear weapons and arms control, which is a good thing. Bird and Sherwin’s biography has now also returned to bestseller lists for the first time since it won the Pulitzer Prize in 2005. I can only hope that the film and the book bring even more people into the kind of important conversations that many of us—including Oppenheimer himself—have been having for years.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: J. Robert Oppenheimer, Manhattan Project, Trinity test, atomic bomb, nuclear weapons

Topics: Nuclear Weapons, Opinion

One of the worst musical scores I have ever heard….loud, overbearing,

disrespectful of the action, just absolute noise. Not sure why this film needed music at all…..the dialogue is important and interesting enough.I am surprised Nolan accepted the music.

The sound mixing in this movie was the worst that I have ever heard. The music in the theater was deafening and most of the dialogue was completely inaudible. Instead of setting a mood, the score just detracted from the movie overall. If I’d known, I would’ve waited and watched it on a streaming service with subtitles.

I immediately caught the use of Mozart’s “Lacrimosa”, part VIII of his Requiem K. 626 (1791), in the Oppenheimer score and thought it so appropriate for its position within the movie as the bomb casings for Little Boy and Fat Man are being crated for shipment to Tinian. In my opinion, Robert Oppenheimer is reflecting during this scene about his lead role effort to create the atomic bomb and where it going to be used next. It is a collective reflection of Trinity, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki along with the unknown hope the upcoming bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki will be… Read more »