Popping the chatbot hype balloon

By Sara Goudarzi | September 11, 2023

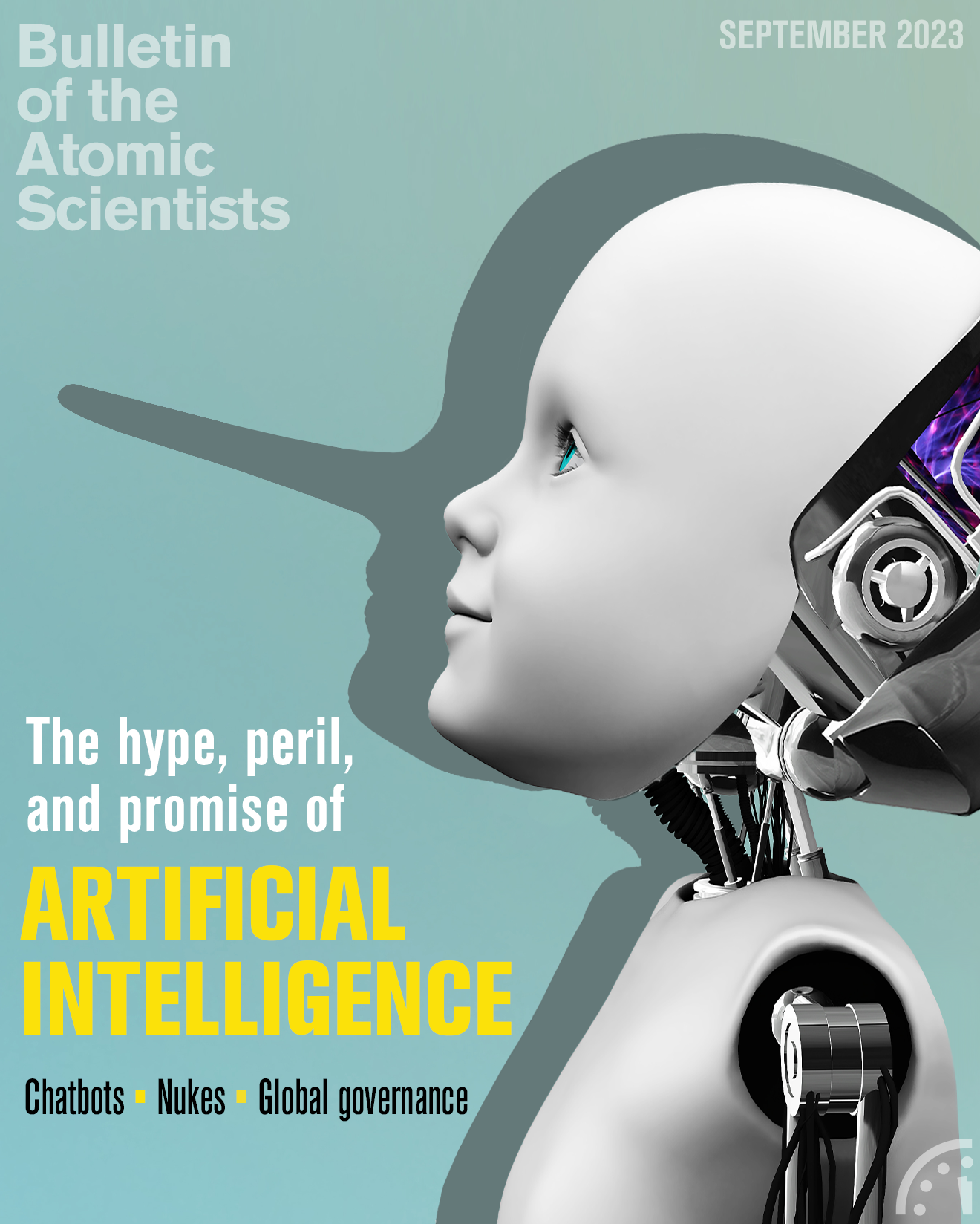

Animation by Erik English under license from vectoratu / Denis Voronin / Adobe.

Popping the chatbot hype balloon

By Sara Goudarzi | September 11, 2023

In 2015, Krystal Kauffman experienced health problems and could no longer work an on-site job. To pay her bills, she looked on the internet for work-from-home openings and came across MTurk. Short for Mechanical Turk, the Amazon online marketplace allows businesses to hire gig workers all over the world to perform tasks that computers cannot. Kauffman signed up and was soon tagging images and labeling and annotating data for tech companies.

MTurk and platforms like it hire hundreds of thousands of workers worldwide to perform quick tasks, typically for small sums, and they have become an important component of machine learning. In this application of artificial intelligence, machines examine given data to find patterns and use those patterns to learn. But machines don’t always perform as intended, and to aid them, throngs of people take on broken bits of large volumes of work, a phenomenon Amazon founder Jeff Bezos has described as “artificial artificial intelligence (Pontin 2007).”

Kauffman is a research fellow at the Distributed Artificial Intelligence Research Institute (DAIR) and the lead organizer of Turkopticon, a nonprofit organization dedicated to fighting for the rights of gig-workers. She knows artificial artificiality firsthand: “You have all of these smart devices that people think are just magically smart; you have AI that people think magically appeared, and it is people like me [who make them work], and we’re spread out all over the world,” she says.

AI has come into the spotlight since the release of OpenAI’s ChatGPT last November. From fascination and excitement to fear of chatbots taking over human jobs and even humans themselves should the AIs go rogue, these applications of artificial intelligence have inspired debate among researchers, developers, and government officials.

The debate has been accompanied by a series of public proposals for slowing or controlling AI research. The proposals have ranged from temporarily banning chatbots, as Italy did with ChatGPT, to an open letter calling for a six-month pause in training more advanced AI systems (Future of Life Institute 2023), to a one-sentence statement of concern regarding their societal risk (Center for AI Safety 2023). One researcher—who believes AI to be a mortal threat to all of humanity—even called for airstrikes on AI datacenters that do not comply with a ban on further research into advanced AI (Yudkowsky 2023).

The current debate about the potential dangers of artificial intelligence has conflated concerns about the negative impacts of chatbots—which have narrow AI abilities that are constrained to the material on which they were trained—with fears that continued AI development will lead to machines that have artificial general intelligence, a capacity to think and improve themselves that might come to rival and then exceed human intelligence. To evaluate the validity of the concerns that have accompanied the release of chatbots, it’s important to understand how chatbots work, how humans are involved with making them work, and why they are revolutionary, but hardly the stuff of Hal from 2001: A Space Odyssey.

The secret sauce is data

Chatbots are powered by complex software arrays known as large language models; they are built using deep learning techniques and pre-trained on large datasets (hence the GPT acronym, meaning generative pre-trained transformer). The text-based models output the most likely sequences of words in response to text prompts and can be tuned to answer questions, generate conversations, translate from one language to another, and to engage in other natural language processing tasks. These models are shaped, and fed by, huge amounts of textual data, often copied or “scraped” from the internet. When a model receives a prompt, it statistically predicts the most likely words that would respond to such a prompt based on the billions or trillions of words it was trained on. That training data can come from a wide variety of digital sources; some of it might be text from relatively authoritative information repositories, but a fair amount can come from the likes of Reddit, Wikipedia, and even the very dark corners of the web exemplified by Stormfront and 4chan.

Meredith Whittaker, president of Signal and chief advisor and the former faculty director and co-founder of the AI Now Institute, says there’s another important step in creating chatbots; it’s known as reinforcement learning with human feedback, or RLHF. “That means there are people there who effectively have to calibrate the system,” Whittaker says, “so it’s not spitting out the gnarliest, least acceptable, most offensive, most terrible things that we know exist in large quantities on the internet.”

An example of such system tuning is a task that Kauffman took on via MTurk, which involved looking at images and reacting, by assigning a “feeling,” to them. With no warning head of time, she was presented with images portraying suicide—a task that can be emotionally and mentally harmful.

“To this day—this was several years ago—I can still see every single picture that I looked at extremely vividly; it never left my brain,” says Kauffman, who has also been tasked with tagging hate speech. The reason those suicide images and specific hate speeches didn’t make it to an end user is because Kauffman flagged them.

Such calibrations, Whittaker explains, help chatbots meet standards of polite, and somewhat liberal, discourse that won’t cause a headline that will make the PR departments for AI developers stay up at night. In addition to the many workers who label data and moderate content, there are millions of people whose data are being used by these models, making large language models highly dependent on humans in one way or another.

“The secret sauce first and foremost is the data,” says Timnit Gebru, founder and executive director of the Distributed Artificial Intelligence Research Institute (DAIR). “So, it’s a lot of human content [and] human labor involved. And I think that there’s an intentional obfuscation of that, because when you know the amount of human labor involved and the amount of data involved, it starts to become less like science fiction.”

The chatbots, the myth, the reality

That obfuscation is perhaps adding to a mythology surrounding large-language models—a mythology that, some experts say, switches the focus from AI’s more immediate risks to ones that are theoretical and at times not grounded in current evidence.

In April, in an interview with CBS’s 60 Minutes (Pelley 2023), Google CEO Sundar Pichai indicated that PaLM, the large language model behind Google’s chatbot Bard, learned Bengali—a language it was never trained on—and said, “some AI systems are teaching themselves skills that they aren’t expected to have.” The statement, if true, would indeed be concerning. However, according to a paper (Chowdhery et al. 2022) authored by several Google researchers, Bengali actually was in a small part of (0.026 percent) of the model’s training data.

“That interview was a scandal; it was ungrounded in any factual reality, scientific basis, or expert consensus,” Whittaker says. “What appears to have happened is maybe they didn’t account for everything in the training corpora. But let’s be clear, these are statistical systems.”

The first machine that might qualify as a chatbot was MIT’s ELIZA, which was developed in the 1960s and interacted with humans using a keyword and predefined scripts to generate responses. The deep-learning techniques using neural networks that are behind today’s chatbots were developed in the 1980s, with improvements over the two subsequent decades. However, there wasn’t much fanfare around these improvements as they occurred.

Those improvements didn’t matter much to the tech industry until the 2010s, when it became clear that “brute forcing” would give these old systems new capabilities, Whittaker says. Brute forcing in this case involved expanding the quantity of training data available, thanks to the internet, and the computational power used for that training. The outputs of these new, brute force chatbots can be impressive, displaying a fluency with language that seems quite sophisticated. But they are narrow applications and definitely not the kind of as-yet-nonexistent artificial general intelligence that might (as some AI theorists project) discard humans as unnecessary or, at best, keep them as pets.

“[That] is part of what is going on with this discourse, why you have Google going out there and saying all these sorts of quasi-mystical statements about these systems, because ultimately that is advertisement for them and for their cloud services business that will be offering these models for third parties to license,” Whittaker adds.

Like Pichai, OpenAI’s Sam Altman has floated the idea that AI systems will progress and, one day, gain capabilities that are beyond humans’. Along the way, he has also advocated for some form of governance around superintelligence (Altman, Brockman, and Sutskever 2023)—more powerful than artificial general intelligence (AGI)—and has compared AI technology to nuclear energy and synthetic biology.

But some experts believe that since AI companies are involved in questionable practices now—data harvesting of online personal information, copyright infringement issues, and other substantive and materially harmful but less-than-existential risks—the advocacy for regulation of artificial general intelligences that do not yet exist is a tactic meant to distract.

“I think this willingness to talk about existential risks certainly helps keep the conversation away from these [other] discussions, which would ultimately affect the companies’ bottom line because it could really affect the valuation that they’re moving from being a revolutionary technology to sitting on a landmine of intellectual property,” says Fenwick McKelvey, an assistant professor in Information and Communication Technology Policy in the department of Communication Studies at Concordia University.

But AI developers aren’t the only ones raising existential alarms. Last spring, Geoffrey Hinton and Yoshua Bengio, both AI researchers and recipients of the prestigious Turing Award, separately expressed concerns over the dangers of generative artificial intelligence. In an interview with The New York Times (Metz 2023), Hinton, who had recently left Google, discussed a variety of fears over the harms that AI could cause, ranging from the spread of misinformation and misuse of AI by bad actors to systems that become smarter than humans. Soon after, Bengio posted a piece (Bengio 2023) laying out conditions that could lead to rogue AI.

“I think it’s a challenge where you see an ability of being a technical expert and assuming you can stand in as a societal expert,” McKelvey says. “The fact that the Bengio and Hinton comments were so well reported shows a deficit in media expertise. Since the initial open letter, there was a real desire to kind of combine abstract existential threats with tangible regulatory reform, and they kind of seemed opposed to each other.”

Just a handful of years ago, there were few AI-powered applications and users of AI. Now, there are millions of active AI system users. With that growth comes a certain amount of public attention that researchers, who are very much in the spotlight at the moment, might not be used to.

“That kind of public attention requires a certain amount of understanding that you’re speaking to the public; public health is an entire field, and the way that public health officials speak to the public is crafted and curated,” says Jesse Dodge, a research scientist at the Allen Institute for AI. “In AI, this has never been the case that we have the public’s attention. And so people like Hinton, I think, often don’t recognize the impact that their words will have. And they aren’t taking that sort of public health understanding of ‘if I described these things publicly, how will the world react,’ because that’s never happened before.”

“So, I think a lot of it is just many people today in our field have [a lot of] technical training and less training with trying to understand the impact of their words will have at a global scale.”

Flawed programs still pose threats

Though the types of risks involved are subject to debate, most agree that large language models are cause for concern. Some of the immediate and concrete risks include the replication of existing biases and discrimination at scale, because these AI systems are trained on, and encode, the internet. These applications also cause harm to creators, harvest personal data (Kang and Metz 2023), spread misinformation, and produce inaccurate responses in an authoritative manner—a much talked about phenomenon known as hallucination.

Hallucination occurs because AI generative tools are trained by taking large amounts of web data and treating all that information equally. To a large language model, information from a reliable encyclopedia could carry the same weight as a person’s opinion expressed on a conspiracy blog.

“When we talk about hallucination, really what we’re talking about is the model recognizes that in language there are often things that are contradictory; there is no one factually correct answer,” Dodge says. “The model has learned that, because that’s what’s in its data. So, to me, that provides pretty obvious evidence as to why we would expect any model trained on the data that we’ve got is going to hallucinate.”

Despite the inaccuracies frequently detected in chatbot outputs, they are increasingly seen as a threat to various sectors of the labor market. In May, the Writers Guild of America (WGA) went on strike against the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers; the strike continues today. The guild is a joint effort of two labor unions that represent more than 11,000 writers who are demanding that AI not be used to write content or provide source material. In July, some 9,000 writers—including prominent authors Roxane Gay, Margaret Atwood, and George Saunders—signed an open letter (The Authors Guild 2023) produced by The Authors Guild that asks AI developers to obtain consent and compensate writers before using their works in the training of artificial intelligence programs, among other demands.

By now it’s clear that generative AI cannot pen a unique narrative the way a human does. But that doesn’t seem to matter in certain businesses, where these applications, despite their failings, can be used as instruments of control that exploit labor. In the case of the writers, generative AI can be employed to diminish the value of their expertise by, for example, producing preliminary drafts and scenarios, even if those in charge recognize the need to have humans involved in producing final articles and scripts.

“There’s sort of a momentum of the hype, coupled with the fact that they [chatbots] don’t actually need to be good for employers to justify firing all the writers, hiring a couple back as contractors and saying, ‘You’re AI editors now,’” explains Whittaker. “The imperative is how do we squeeze more out of workers? Well, this is a great pretext; it doesn’t have to work.”

Chatbots are impacting writers and other creators in another way: Large language models are trained, in part, on the work of the same writers and artists who could lose their jobs if chatbot-produced text and images become widely used in television, movies, journalism, and other pursuits that employ large numbers of writers and artists.

“All of these artists and writers whose work is being basically stolen—to create something very mediocre, but that could pass as something quote unquote artistic so they can lose their jobs—is a big problem,” Gebru says. “Why are you trying to replace a big portion of the labor market with their own work without compensating them?”

Existing regulations around copyright and fair compensation of writers and visual artists don’t account for current practices in generative AI, in which a handful of corporations take massive amounts of people’s work from the internet—without permission or compensation—and use that data to train models that will produce writing and visual art.

“I think we need some kind of new regulation that either expands on the current definitions of, for example, copyright, or just something completely new,” The Allen Institute’s Dodge says. “And the reality is these systems as they become more and more ubiquitous, they are going to earn a profit; they are going to drive some of the economy, and frankly I think it’s in our future and vitally important for the creators of content to be fairly compensated for their work. And right now, there’s none of that.”

But regulation has proven tricky thus far. In May, in a Senate hearing, Altman agreed with lawmakers on some of the harms that could be caused by generative AI, such as the spread of disinformation and the need for disclosures on synthetic media. And while he seemed agreeable to regulation in that setting, Altman threatened to pull ChatGPT from Europe (Reuters 2023) if the EU’s AI Act proved to overregulate artificial intelligence.

“This is a very common theme historically, where people who are innovating say ‘you should regulate my competitors; you should restrict them from building systems that are as capable as mine because the way they might do it is dangerous. But I am doing a good job and I am taking into account the things that we need to consider, so don’t regulate me,’” Dodge says.

Behind the curtain

On July 21, the White House (The White House 2023) announced that the administration has “secured voluntary commitments from [seven AI] companies to help move toward safe, secure, and transparent development of AI technology.” These companies include Amazon, Anthropic, Google, Inflection, Meta, Microsoft, and OpenAI. Whether these commitments constitute a step towards meaningful regulation remains to be seen. It’s also uncertain in which direction these companies will go and what effects their systems will have on society.

“I think that the goal of OpenAI is to be the super renter, where everyone basically uses their models and builds on top of their models,” Gebru of the Distributed Artificial Intelligence Research Institute says. “So, their goal is for literally everybody who does anything that has anything related to the internet to use them and pay them, and I really hope that that’s not where we end up.”

Further, because these systems are tremendously expensive to create and operate (the ChatGPT interface is reported to cost $700,000 a day to run) (Mok 2023), only a handful of corporations and institutions are able to use them.

“So, the question of who gets to use them on whom becomes really fundamental to understanding how they could be used to exacerbate racialized exploitation, to exacerbate extracting more labor from workers, to how it is used at border by law enforcement,” Whittaker says.

And while these companies stand to generate large amounts of cash (OpenAI projects it will have revenue of $1 billion by 2024) (Dastin, Hu, and Dave 2022), many of the gig workers who help these systems run are paid pennies for the tasks that they undertake.

“They could definitely afford to pay more for the training, but they would rather keep this whole giant global workforce behind a curtain and let the world think that just AI just appeared; it was our wonderful engineers, and now there’s this magical thing. And [they] keep the people who are actually programming and trying to catch the inappropriate things quiet, keep us hidden, and it’s been going on for years now,” Kauffman says.

Amazon’s Mechanical Turk platform is named after a machine built in the late 1700s that could play chess with humans. The Turk consisted of a large box with a chessboard on its surface and the torso and head of a man attached to it. Considered an automaton, the Turk played a competitive game of chess and quickly became a marvel. It wasn’t until half-a-century later when it was revealed that the self-operating machine was in fact a hoax and contained a human operator hidden in a compartment of the box.

It’s hard not to draw a parallel between the concealed human inside the Turk and the thousands of AI laborers that are largely hidden from the public. But while the Turk was rebuilt in the 1980s to function without a person running it during operation, it’s unlikely, at least for now, for chatbots to work without human intervention.

“There’s always going to be a need for people, humans to keep this programmed, to keep it running correctly,” Kauffman says. “For example, we’ve run into different things where a language model will learn something incorrectly, and if nobody corrects that it keeps learning on that wrong bit of information. So, you might have a product in five years that started learning off of one bad bit of information; that could come out at any time, and when it does, it’s going to have to be fixed. It’s going to have to be humans are going to have to go in and look at it.”

The question, then, isn’t whether humans will play a role in these machines, but whether the owners of these technologies—which are built on human labor, public knowledge, and personal data—will be held accountable and give back to maintain and protect the resources they have utilized.

“I think it really is about how we see the internet as something which is a public resource that we ultimately want as a society to protect and defend,” McKelvey says.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: AI, ChatGPT, artificial intelligence, chatbots, large language models, machine learning, neural networks

Topics: Special Topics

Fantastic article! These chat-bots are money losers and the efficiency of neural networks is very low, when compared to a specific piece of code aimed at a real application, other then generating more garbage on the net. They are glorified browsers and have no chance of replacing necessary workers in engineering or computer science. The mania surrounding this technology rivals the dot com era .Machine learning has been around for 50 years and is used already in all of Apples products and in voice recognition systems. ML can be used for a myriad of applications that a very specific ,but… Read more »