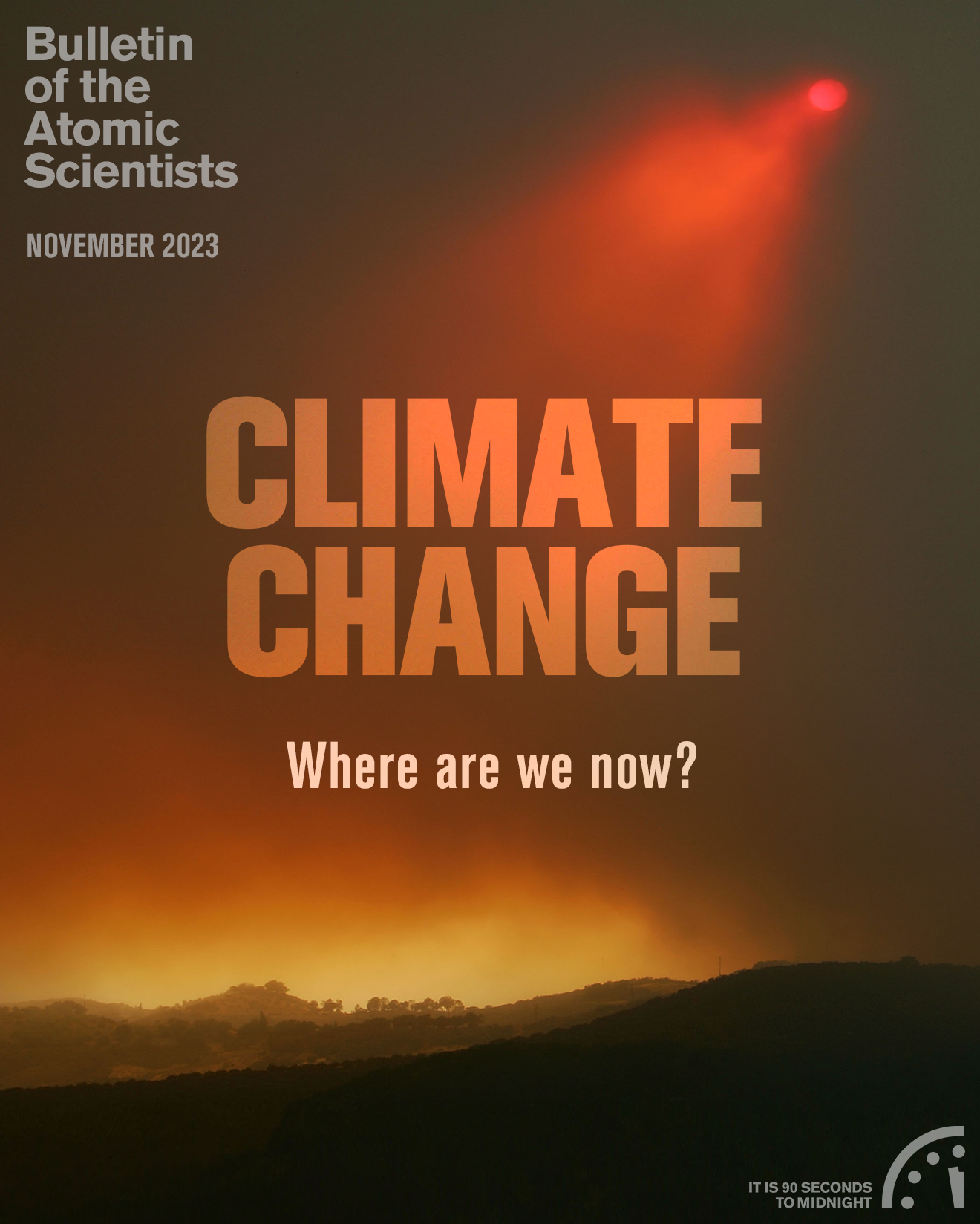

Where climate journalism is now: Interview with Emily Atkin, the fire behind the Heated climate newsletter

By Dan Drollette Jr | November 8, 2023

Where climate journalism is now: Interview with Emily Atkin, the fire behind the Heated climate newsletter

By Dan Drollette Jr | November 8, 2023

In September 2019, after six years of covering climate politics for various news outlets in Washington, D.C., journalist Emily Atkin decided to strike out and form her own, one-person weekly climate newsletter—despite what can only be described as difficult headwinds for journalism. She named it Heated and accompanied it with the tagline: “A newsletter for people who are pissed off about the climate crisis.”

On the About[1] page of the newsletter’s Substack, she laid out a manifesto: “It is not your fault that the planet is burning. Your air conditioner, your hamburger, your gas-powered car—these aren’t the reasons we only have about a decade to prevent irreversible climate catastrophe. No; the majority of the blame for the climate emergency lies at the foot of the greedy; the cowardly; the power-hungry; the apathetic. And that’s why I created this newsletter: to expose and explain the forces behind past and present inaction on the most existential threat of our time.”

Her approach—sharp-witted, deeply reported, with a dose of angry humor—seemed to have struck a chord. Within a week after her story about misleading fossil fuel company advertisements,[2] a presidential candidate was tweeting it out. The Columbia Journalism Review cited it as “outstanding climate journalism … despite the hellish intensity of the present news cycle.”

And the newsletter, initially free, saw its number of subscribers climb from zero in 2019 to 76,706 as of August 2023, according to what Atkin found in the analytics of her Substack account while talking to me.

In this interview with the Bulletin’s Dan Drollette Jr, Atkin looks over the current landscape of climate journalism, describes what drove her to quit her full-time job and form her own newsletter, details the problems with current climate coverage, and gives her own prescription for making it better.

(Editor’s note: This interview has been condensed and edited for brevity and clarity.)

Dan Drollette Jr: Your newsletter certainly gets right to the point; its full title is Heated: A newsletter for people who are pissed off about the climate crisis. The no-holds-barred approach kind of reminds me of the late political reporter Molly Ivins, who had a way of cutting politicians down to size—and injecting some cutting satire, too. And that’s what I pick up here; you’re not afraid to go after those who need to be brought to heel.

Emily Atkin: That’s how I was taught to be. My mentor was investigative journalist Wayne Barrett, and he was exactly like that. He was based in New York his whole career and was known and revered—sometimes hated—for his no-bullshit approach to calling out and investigating politicians on both sides of the aisle. He wrote a book called Trump: The Deals and the Downfall, investigated [Republican] Rudy Giuliani—but also did investigative reporting on [Democratic New York Senator and Majority Leader] Chuck Schumer and Andrew Cuomo, a Democrat and former governor of New York. This was how I was taught to be the most effective type of journalist. Wayne did journalism on behalf of the people in his community, not the people in power.

Drollette: You wrote an essay for the Columbia Journalism Review[3] where you quoted a line from Jack Newfield of The Village Voice: “Knowledge without anger can stagnate into mere cynicism and apathy. Anger improves lucidity, persistence, audacity, and memory.” You went on to say: “That’s how journalists of the past were effective, and that is how we will be effective now.”

Atkin: Well, you know, Jack was Wayne’s mentor at the Voice. Consequently, I feel like that quote—that approach to journalism—really freed me. Because according to what they teach you in J-school, once you let your feelings in, you’re out of the bounds of journalism.

Drollette: But you’re still fact-based…

Atkin: Yes.

Drollette: …and you’re trying to still retain that sense of authority—while also giving a personal take on what you find.

Atkin: If you’re not speaking to the emotional depths of a situation—and I think there is a lot of anger about climate inaction, and justifiably so—then you’re not allowing yourself to understand and feel what is really going on. And I think that means that you’re not really telling the climate story fully and accurately.

As a reader, you can tell that it’s not being told accurately, because those feelings aren’t there. They’re not reflected in the reporting, and then the article doesn’t resonate with people.

And that’s a complaint you constantly see about climate reporting: Journalists say they don’t know why people aren’t reading their climate coverage, and the answer is it’s because they’re not really capturing what is happening.

You are supposed to not be just regurgitating data but telling a story. And the most compelling story out there is what is happening with the climate.

But there is, as you can guess, some resistance to this kind of approach.

Drollette: So, fact-based but passionate.

Atkin: And sometimes outraged.

I’m such a stubborn piece of work, you know. I’ve got this New York thing going on where I’m like “I’ll take no money from big shots—rich people—to fund this newsletter.” It’s like I believe in what I’m doing so much that sometimes it can choke me; that’s why it took me so long to hire somebody. Because I couldn’t let go; I kept thinking that I alone needed to be the one doing this newsletter.[4]

Drollette: Do you have a favorite article from Heated? One that really jumped out at me was the one called “Who gets arrested for climate crimes?”[5]

Atkin: You know, I think that there are so many different types of articles that have been done on the newsletter that it’s hard to pick just one. My favorites are the ones that opened my own eyes more, in which the reporting really furthered my own understanding of climate change, even after 10 years of reporting on it—such as a piece on the beauty industry and climate change. Because there’s always so much more to learn. Right now, I’m just so interested in these discussions about colonialism and climate change.

I got a lot of response to a Heated piece that called Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, and Bill Gates “climate colonizers”—the idea being that they have a mentality that doesn’t consider what the climate needs from humans, they only think about what humans want from the climate. They want to bend nature to do their will, and they want to be doing the bending.[6]

Drollette: What emerging stories do you see?

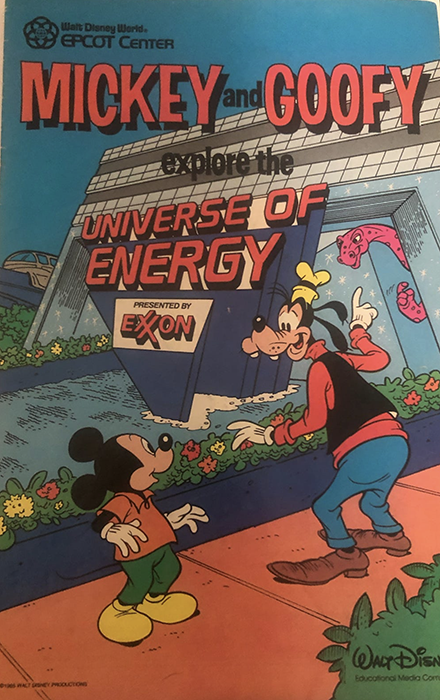

Atkin: Fossil fuel influence in schools, in order to groom children into loving fossil fuels and believing that climate change is not a problem. And that keeps me up at night because those kids are gonna grow up in a climate-changed world. It comes across to me as super evil, and it’s been going on, under the radar, for a long time.

Did you know that in the ‘80s, ExxonMobil went into partnership with Disney to produce Mickey Mouse comics that were like, “Wow, Goofy, don’t you just love fossil fuels?”[7]

Drollette: What drew you to climate change in the first place? Was there one “Aha!” moment? And how did you decide to do it by creating your own climate newsletter from scratch?

Atkin: I think people assume that because I’m a climate change reporter, that I must be an environmentalist at heart. And they think that because I’m not shy about reporting with my feelings, that I must have been a person who was always interested in climate change.

But that’s just not the case.

I was a person who was interested in journalism at heart and passionate about uncovering corruption, speaking truth to power, giving voice to the voiceless—all of those things.

But I was also a 23-year-old looking for a job and couldn’t find one.

What was really my dream back then was to be a political reporter in New York, but that was just very hard to find. So when I saw a job advertised in 2013 for a climate change reporter in Washington, D.C., I thought to myself: “Well, if I can’t get a political reporting job, maybe I can get this job.” My attitude was that “the political reporting jobs are super-competitive, but this climate change reporting job—I mean, who’s going out for that?”

And I figured that once I could get my foot in the door, then I could do what I wanted to do.

So I that’s what I did. I got the climate change reporting job. And then I did use that to move into political reporting.

But once I got into political reporting—in particular, the 2016 election—I realized the politics beat was not what I really wanted, because it wasn’t really scratching my itch for the kind of journalism that I wanted to be doing. I realized that my reporting work on climate change had far more impact. There were more opportunities in the climate change area for uncovering corruption and wrongdoing, and to really explore the effect on the vulnerable of the inaction of the powerful.

And then, eventually, I found that doing climate change journalism for a mainstream, establishment outlet meant that I was always fighting to get my perspective across, arguing with editors and people who had preconceived notions about what climate coverage was supposed to be. It just got so frustrating that I decided to go out on my own and see if my ideas about climate reporting really could work. If they failed, I would at least know they didn’t work.

Drollette: Still, it must have been a scary moment.

Atkin: Absolutely. But then again, it’s not like I felt a massive amount of stability, being at The New Republic, where I was in the first place.[8] Let’s face it, journalism is a notoriously unstable profession.

And besides, you don’t go into journalism because you desire money and stability. Obviously, I need those things to survive—and I want them—but I think that people go into journalism because they really believe in the good that it can do and the impact that it can have. And if that wasn’t happening, then why was I even here? I might as well be in public relations or something similar.

Drollette: Do you think the nature of the resistance to climate change has changed?

Atkin: Yes and no. I think that there was a time—before Trumpism—when outright climate denial was going away. They were switching to something that at least sounded more reasonable regarding delay in fighting climate change—such as “It’s too expensive” or “These technologies aren’t ready.”

You still see some of that, but I think that there has been an astounding resurgence in outright denial in the last couple of years. I see just as much outright climate denial now as I did when I started climate reporting in 2013.

To give you some background, when I started climate reporting in 2013, I actually didn’t know which of these anti-climate change talking points were denialist and which had merit. So when I started, I did a lot of immersive fact-checking on all of these points, and approached them as if they actually had merit—I mean, that’s what a responsible journalist does.

[So] I’ve already done the fact-checking, and I am hearing the exact same stuff over and over from the denialist camp. They’re just regurgitating the same old talking points from 2013: “It’s too expensive. It’s not ready.” These statements have been documented as manipulative ploys in papers on the discourses of delay; if you go and look at these studies, there’s nothing new in the climate denial and delay space.[9]

If I saw something genuinely new, I would be really interested in exploring it and doing the exact same things I did earlier in my career—but unfortunately, the discourse has stayed the same. It only appears new if you haven’t been there for the whole time, or haven’t studied the history of climate change denial.

And that’s essentially why I take such a hard-nosed approach to reporting about climate denialism: There is no history of truth-telling when you’re dealing with people who don’t want to take climate action. Generally, the history is a bunch of bad-faith arguments or outright lying.

Drollette: The idea of a resurgence in complete, total outright denial of climate change is unexpected for me, because what I see in our reader comments is a decline in that sort of thing since I started here in 2014. I suppose possibly that could be because our readership at the Bulletin tends to put much more trust in science and scientists; after all, we were founded by a bunch of physicists; our whole mission is speaking scientific facts to policy makers. And our specialty is the first-hand report from the expert, such as the oceanographer who effectively says: “I just returned from a three-month expedition to the Thwaites Glacier in Antarctica, and here is what I found.”[10]

Atkin: Well, I think it’s fantastic to hear that, from a scientific perspective and a policy perspective. But I was talking about just everyday people in the political sphere. Because what I focus on as a journalist is what is happening politically—what is being published in the opinion pages? What are reporters considering to be both sides when they are covering a story?

I would argue that there is a lot more discourse now calling for a delay when it comes to dealing with climate change—and delay discourse is akin to denial discourse; you’re putting both of them on the same pedestal and engaging in false balance.

But on a more human level, I think that the reality of what we’re experiencing with climate change is extremely unreasonable, right? This is the reality. And the average person wants to be reasonable. So they kind of think that it doesn’t seem reasonable to accept this very unreasonable reality. “The hottest days in the history of taking temperature readings” seems screeching; it seems it seems like an overreaction—even though it’s true.

So, I think a lot of people feel comfortable only if they settle into the middle. The default attitude is that climate change is a problem, but we can move slowly and take our time, because that feels good. It feels like you’re being reasonable, and in the middle.

And I understand that. I was very much non-confrontational as a kid. People are usually very surprised to hear this, but when I was growing up, I really hated to be on one side of an argument. My parents always told me that I should be a diplomat because of my desire to always see both sides of any situation. And that’s one reason why I went into journalism—because of this innate desire to want to learn of everyone’s perspective.

So it’s odd to see where I ended up—but I guess that was because I found that so much of climate denial was based on outright lies. After all, ExxonMobil knew about anthropogenic climate change way back in the early ‘80s, if not earlier. And they deliberately chose not to deal with it; they found it cheaper and more financially beneficial to deny that human-made climate change existed at all. And then the fossil industry ran all these advertisements saying things like anyone who worries about climate change is a modern-day Chicken Little.[11]

And then you have the Greenpeace journalists who got that ExxonMobil executive on tape saying that “the only reason we advocate for carbon tax is because we know it’ll never happen.”[12] So when ExxonMobil says “We advocate for climate policies, we advocate for a carbon tax, we’re working on it,” my response is “I’m pretty sure you just lied.”

Drollette: I heard an environmental journalist say that he finds it peculiar that climate change is relegated to a little boxed-in corner of the journalism world. We’ll know that climate change has been accepted by the mainstream news media when we see it covered in the real estate sections and the business sections instead of consigned solely to the science page in the back.

Atkin: I think every journalist should be a climate journalist. And if they aren’t, they soon will be, because if you haven’t incorporated it into your beat, it will get incorporated for you, because climate change affects literally everything.

One of the best climate stories I’ve ever read—and I really wish that I wrote it—was about this woman who went to South Florida and pretended to be interested in buying a house on the waterfront. She went to all these fancy coastal properties and said to the realtors: “So I’ve heard about sea level rise. What is gonna happen to this house? What are the projections for this area?” And the responses were just outrageous—and very funny.[13]

It’s cognitive dissonance—deep down, these people must know. But they just don’t want to think about it. Or they think “It can’t happen to me.” Or that it will happen so far in the distant future as to not be a problem to worry about right now.

Drollette: Do you think that this newsletter is helping to shift the national conversation?

Atkin: I know that I’m never going to change the Wall Street Journal or Fox News. So, I can’t point to my own contributions specifically. But I can tell you that since Heated was launched, I have far more competitors. So I think Heated is helping to push the media envelope. When I started in 2019, I had essentially no competitors. Now I compete with every other climate newsletter out there that has launched since I launched Heated.

And I think that any change in climate reporting is not just due to me; Amy Westervelt has been doing this for years with her Drilled News podcasts, for example.[14] But I do think that the cadence of climate accountability reporting has changed a bit—for whatever reason—in a way that I don’t think existed before.

And the thing about having an impact in journalism is that you can’t always calculate it. It’s not one of those things that will have these nice metrics. At the end of the day, you can get a general sense of things but it’s really an art; it’s not reduced to something easily quantifiable.

Endnotes

[1] See https://heated.world/about

[2] See “Introducing: The Fossil Fuel Ad Anthology,” Heated, Emily Atkin, December 13, 2019 https://heated.world/p/introducing-the-fossil-fuel-ad-anthology

[3] See “Good Grief,” Columbia Journalism Review, Spring 2020, by Emily Atkin. https://www.cjr.org/special_report/good_grief.php

[4] A few months before this interview, Atkin hired Arielle Samuelson, “a mid-career journalist, older than I am, whose judgement I could trust” to help with putting out Heated every week. Atkin said: “Heated is worker-owned. Arielle and I make the same amount of money, take the same amount of stock, have the same percentage of profits, and we leave the rest to someday hire another person.”

[5] See “Who gets arrested for climate crimes? People protesting the climate crisis are getting arrested around the world while actual alleged climate criminals walk free,” Heated, Emily Atkin and Arielle Samuelson, July 18, 2023 https://heated.world/p/who-gets-arrested-for-climate-crimes

[6] The piece says “Musk is popularizing electric cars so we can keep driving everywhere. Gates is pushing carbon capture so we can keep using fossil fuels. Bezos is trying to move millions of humans to space while extracting energy from other planets so we can keep emitting carbon, but on other planets.” See “The climate colonizer mentality,” Heated, Emily Atkin, October 12, 2021 https://heated.world/p/the-climate-colonizer-mentality

[7] See “When Exxon used Mickey Mouse to promote fossil fuels,” Heated, Emily Atkin, March 5, 2020 https://heated.world/p/when-exxon-used-mickey-mouse-to-promote

[8] Atkin has worked fulltime at a number of journalism outlets including The New Republic, Sinclair Broadcast Group, and ThinkProgress, among others. Her freelance writing has appeared in places such as Slate, Mother Jones, Sojourners, CityLab, and The Hill. In addition, she’s appeared on MSNBC, CPAN, and NPR.

[9] See “Cranky Uncle: The smartphone game designed to fight climate denial,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, December 4, 2019, by John Cook https://thebulletin.org/2019/12/cranky-uncle-the-smartphone-game-designed-to-fight-climate-denial/

[10] See “Peter Davis of the British Antarctic Survey on changes in the Thwaites Glacier,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, May 1, 2020, by Dan Drollette Jr. https://thebulletin.org/premium/2020-05/peter-davis-of-the-british-antarctic-survey-on-changes-in-the-thwaites-glacier/

[11] In 1991, a front group for a collection of fossil fuel and utility companies calling itself “Informed Citizens for the Environment” ran a series of ads claiming that the evidence for climate change was “weak,” the proof “non-existent,” the climate models “inaccurate,” and that the physics was “open to debate”—while knowing the opposite, as subsequent records revealed. For more, see “The forgotten oil ads that told us climate change was nothing,” The Guardian, November 18, 2021, by Geoffrey Supran and Naomi Oreskes. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/nov/18/the-forgotten-oil-ads-that-told-us-climate-change-was-nothing

[12] See “ExxonMobil lobbyists filmed saying oil giant’s support for carbon tax a PR ploy,” The Guardian, June 30, 2021, by Chris McGreal. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/jun/30/exxonmobil-lobbyists-oil-giant-carbon-tax-pr-ploy

[13] See “Heaven or High Water: Selling Miami’s Last 50 years,” Popula on-line, Sarah Miller, April 2019. https://popula.com/2019/04/02/heaven-or-high-water/

[14] See Drilled News at https://drilled.media/

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: 2024 election, Emily Atkin, Heated, climate change, climate change activism, climate journalism, energy, environment, extreme heat

Topics: Climate Change