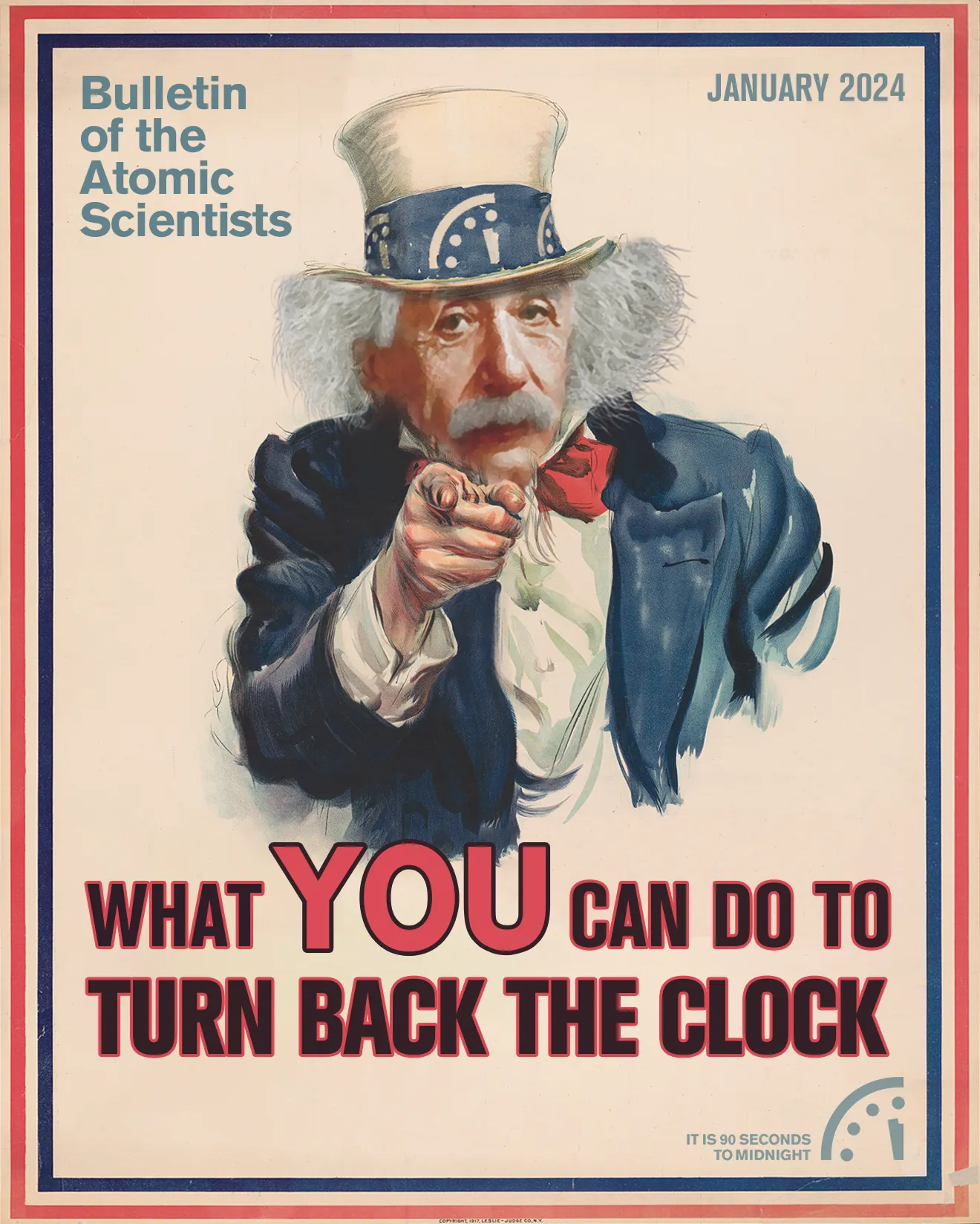

Bill McKibben explains what individuals can do to win the climate fight. Together.

By Jessica McKenzie | January 15, 2024

Bill McKibben explains what individuals can do to win the climate fight. Together.

By Jessica McKenzie | January 15, 2024

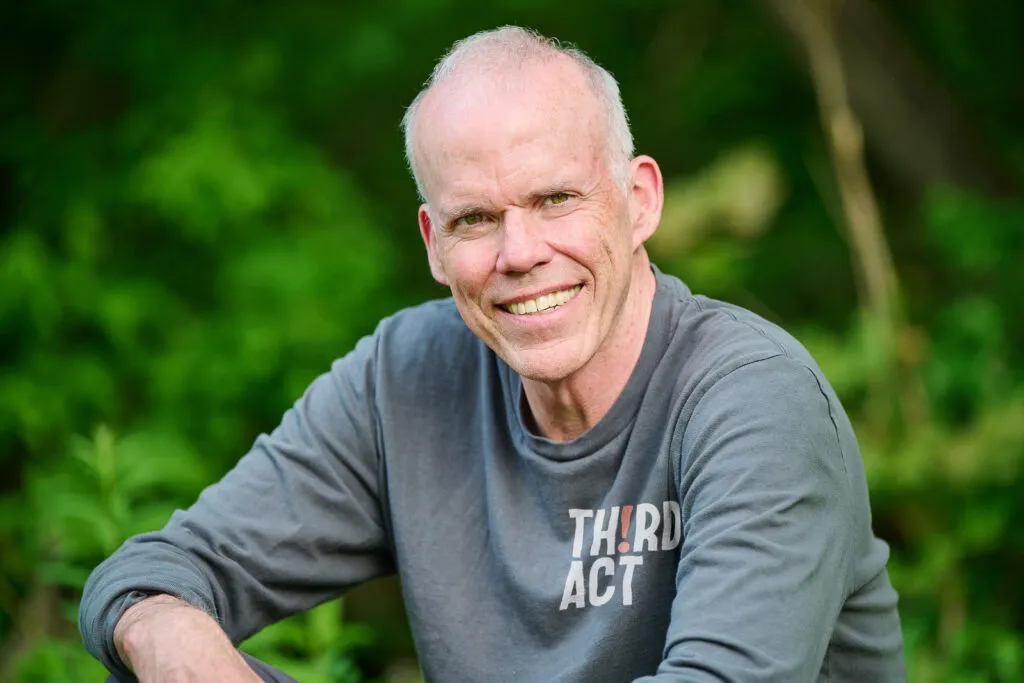

Few writers have chronicled the age of climate crisis as closely as Bill McKibben over the past 35 years, and even fewer have done so while also kickstarting multiple environmental groups and advocacy campaigns for climate action. He has kept the pulse of the crisis, and the movement to address it, since first covering the climate debate—as it was then—for the New York Review of Books in 1988.

The Bulletin caught up with McKibben late last year to get his most recent reading of the climate movement (“we’re not exactly triumphant”); of promising scientific and technological advancements (“there’s really no technological or economic obstacle to…ending large scale combustion on planet Earth”); his take on politics (“if Donald Trump gets back in power, then God help us all”); voting (“you’re not trying to pick a great person, you’re trying to pick the [better] person”); this single biggest looming climate threat (“US expansion of [fossil fuel] exports”); and running out of time (“if we don’t win soon, we won’t win”).

(Editor’s note: This interview has been condensed and edited for brevity and clarity.)

Jessica McKenzie: I was wondering if we could start just by taking stock of the global climate movement. How do you think things are going?

Bill McKibben: The success or failure of the global climate movement is obviously measured by how high the temperature is. And the temperature is higher than it’s been in 125,000 years, at least, this year. So I think you’d have to say from that, we’re not exactly triumphant. In the context of the Bulletin, there are now large explosions going off all the time, as it were, and we’re losing whole regions of the planet to famine, to desertification, to flood, to fire. And those things, in turn, are setting off enormous feedback loops of their own. The fires in Canada are so big this year, that they’ll produce twice or three times as much carbon as Canada produces in an entire year with all the heating and flying and cooking and heating and cooling that it does. So we’re in a very hard place.

McKenzie: It’s not great.

McKibben: If you want to think a little more positively, we’re also in a moment of extraordinary opportunity. The scientists and engineers have done a tremendous job in lowering the price of solar power and wind power by 90 percent over the last decade. We now live on an Earth where the cheapest way to produce energy is to point a sheet of glass at the sun. And that means there’s really no technological or economic obstacle to making very, very rapid progress—no real obstacle to ending large-scale combustion on planet Earth for the first time in hundreds of thousands of years. Because we don’t need to be burning stuff anymore. We don’t need small fires under the hood of our cars, we don’t need small fires in our basements, in our furnace, we don’t need them in our kitchen, we don’t need them in our power plants.

Because we could rely instead on the very large fire burning 93 million miles away, whose rays we can catch on our solar panels, which also by differentially heating the Earth creates the winds that blow those turbines. And so, in that sense, it’s a remarkably hopeful moment. The challenge is that, for any of that to matter, it has to be done fast. Because unlike other problems that we’ve been up against, this is a very time-limited one. And if we don’t quite quickly manage to shut down fossil fuel and replace it with renewable energy, then the amount of energy that the planet uses and will continue to use, will produce so much heat that we’ll just be overwhelmed.

I wish I could tell you that I knew what the outcome was going to be here. And I wish that the outcome was going to be that we knew we were going to carry the day, but I can’t tell you that. We don’t know.

McKenzie: So those are big technological wins, specifically. Those are undeniable. Are there any sort of more political wins?

McKibben: So the climate movement’s job is to catalyze that reaction, to make it happen faster than sheer economics would do. I mean, 40 years from now we’ll run the planet on sun and wind, because it’s cheap, but if it takes us anything like 40 years to get there, then it’ll be a broken planet we run on sun and wind. So the job of the movement is to speed up that transition.

And it can do that I think, basically in two ways. One is to get in the way of fossil fuel. And the other is to push hard for renewable energy. And I think they both have to be done.

There’s been a significant victory in this country on the second task with the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act. It’s the first time in the 35 years that we’ve known about this problem that Congress has actually acted. And they acted.

You know, it’s not what we needed exactly. But for the current Congress in its dysfunction, they acted with actually surprising vigor. And the IRA has a lot of money that I think now being spent —some of it anyway—wisely in an attempt to speed things up.

So some of that is underway, here and around the world. The only reason the IRA passed is because people built this huge constituency, demanding that it happen. By the time we got to the 2020 presidential primaries, Democratic voters were telling pollsters that climate was their number one issue. If that hadn’t happened, then the IRA wouldn’t have happened.

The other half of the equation is trying to stop the fossil fuel industry. That’s going, I think, worse. We’ve had wins, like the Keystone pipeline, but not enough. And we’ve had some significant losses in the last year, maybe most powerfully, this Willow oil complex in Alaska, which the Biden administration unwisely signed off on. I think that the next, maybe decisive battle of the next year or two, is going to be this one over the export of fossil fuels, particularly natural gas—particularly out of the Gulf Coast.

Because it’s so huge. The US expansion of exports is the single biggest factor, in growing the world’s fossil fuel infrastructure, and by quite a bit. More than half of the expansion of the fossil fuel industry in the next 10 years is going to come from the US, Canada, Australia, Norway, and most of that is coming from the US. And mostly it’s exporting fracked gas around the world at extraordinary climate cost. This is dirtier than coal. It’s as if we’re developing a whole big coal export plan at this point.

People are mobilizing to stop it. That’s what I’m spending most of my time working on. And there’s lots and lots of other people doing the same.

And I think we have a chance of convincing the Biden administration to pause this build-out of gas export. Already, quite a bit of it’s been done, some of it under the cover of needing to supply Europe in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. But we’ve got enough to do that now. And we don’t need more. Each increment more, we delay the time that we’ll actually stop using fossil fuel, because these things are built to last 40 years.

McKenzie: Do you think sort of climate activists are stumbling in some way, or the headwinds are just so great…

McKibben: I just think these are always hard fights. The fossil fuel industry is probably, in the last year or two, the most profitable industry in the world. And they have extraordinary political power. They own one of our two political parties in this country, and they terrify the other one. And so each win is a massive challenge, each fight is huge.

McKenzie: When we last spoke in 2021, your final message was to tell individuals to be less individual, to work together. What does that look like right now?

McKibben: For me, it looks like organizing this thing called “Third Act.” And Third Act aggregates people like me, i.e. old people. It’s gone really well. We’ve gotten 65,000 or 70,000 volunteers now, chapters in pretty much every state in the country. And we organized huge demonstrations in March, we had 100 demonstrations in 100 cities against the banks that fund the fossil fuel industry. So I think we’re doing a pretty good job of bringing another front in to help the youth and the frontline communities and all the others who have been fighting the good fight here.

McKenzie: Do you think different generations can or should play different roles within the climate movement?

McKibben: I think younger people probably are and should be mostly in the lead, because they’re going to have to live with this a long time. I’ll be dead before the worst of it kicks in. But if you’re 20 right now, you’re staring down the barrel of this for your whole life. But I don’t think that young people have the structural power to make the change we need in the time that we have by themselves. I think they need a lot of help from the rest of us. And those of us who have hair growing out our ears also have power coming out our ears in some ways. There are 70 million people over the age of 60 in this country. We punch above our weight, because we all vote; there’s no known way to stop old people from voting. So we’re committed to bringing those people out in support of a world that works.

McKenzie: You’ve talked about power. How does money factor into that?

McKibben: There are two levers big enough to pull worth pulling. One’s marked “politics,” and we’ve got to keep hard at work on that. If Donald Trump gets back in power, then God help us all, especially on climate stuff. I think definitely he’ll use up the time that we need. So it’s important to keep pulling that lever. I don’t think we’re going to get more out of Congress anytime soon. I think the IRA will represent their high watermark for quite a while.

The other lever’s marked “money” [or] finance, Wall Street—whatever you want to say. We’ve got to keep pushing hard on these guys. Because if they would cut off the money supply to the fossil fuel industry, then they couldn’t keep doing what they’re doing. But these guys are such, you know, they’re amoral, and I’m afraid they’re greedy. So they’ll continue the endless financing of essentially suicidal projects for our civilization.

McKenzie: So we’ve already brought up the election. Looking ahead to 2024, what are some of the most important demands that people should be making of their political leaders at every level of government?

McKibben: I think the demands increasingly are coming from the planet itself. I mean, we’ve just seen this year, the hottest weather in at least 125,000 years. Next year is going to be hotter, because El Niño is just kicking in a huge way now. So we need leaders who respond to that. And we desperately, desperately need to avoid leaders who won’t respond to that—that may be even more important at this point. Because civil society and scientists and the engineering has some momentum now.

And what we most need is just to keep the truly terrible people like Trump out of power and out of the way. So I think the demands will be [that] since the planet is speeding up the pace at which this heating is underway, we need our leaders to speed up the pace of solutions. At this point, talking about 2050 seems a little absurd, you know?

McKenzie: In what way?

McKibben: Because the destruction of the planet is happening in real time, month by month. I think this decade will prove to be the absolutely crucial decade. The IPCC told us that we needed to cut emissions in half by 2030, to have any chance of meeting those Paris targets; 2030 is only six years away. That’s a lot of work to get done in a short, short period of time. And if we put it off, kick the can down the road, that’s basically the new form of climate denial. It’s reality denial.

McKenzie: You’ve already mentioned how much older generations vote. But can we talk a little bit about the flip side, the lower rates of voting among the generations that have expressed the most concern about climate, and what to do about that?

McKibben: I understand why people get fed up with a system that doesn’t produce as well as it should. On the other hand, the last time around, people voted—young people in particular, in the Democratic primaries—[and] they voted on climate. Biden paid attention, he and Bernie put [the executive director of Sunrise Movement] Varshini Prakash and AOC (Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez) and some others on the committee to come up with the kind of Democratic plan that was a version of the Green New Deal—which, you know, once it had gone through Joe Manchin, was much smaller than it had been before, but still more impressive than anything that had come before. If we hadn’t had that groundswell of electoral support, we never would have gotten it. If we’d lost one Senate seat, we never would have gotten it.

I get why people get discouraged, but I don’t completely understand it, either. Because it does not strike me that voting is a kind of moral act. It strikes me as a completely practical act.

You’re not trying to pick a great person, you’re trying to pick the person, that in a binary choice, will be better than the other one, that you’ll be able to pressure more than the other one, that might listen to you some. And those choices always seemed very obvious to me. But it also is really important that people continue to understand that politics isn’t just about voting. The day after Election Day, and the month and the year after are just as important, because you’ve got to keep the pressure on all the time if you want change. So let’s hope that people swallow their disgust and go out to the polls. Because you know, in the autumn of even numbered years, you have a lot of power, in your vote. The rest of the time, you have to figure out other ways to have power.

McKenzie: Is there anything in particular that people should look for in more local representatives, either at the city level or at the state level?

McKibben: Absolutely. Some real commitment to implementation. People no longer have quite the same excuse, because there really is money available from the IRA to get stuff done. So it’s time to ask who’s actually figuring out how to access that.

At this point, we don’t really need more people piously telling us that they believe in climate change. If you don’t believe in climate change at this point, you need your brain examined. We do need people who tell us “here’s how we’re going to cut emissions in our city, county, state a lot in the next year. And here’s how we’re going to figure out how to pay for it.” It’s not impossible at this point. I mean, as I say, we live on a planet where the cheapest way to produce more energy is to point a sheet of glass of the sun. So we need people who can run with that.

McKenzie: I feel like the media, news organizations, should play a big role in getting those answers—getting politicians on the record. This issue of the magazine is focused on what individuals can do—so how can individuals demand more of their media, to demand more of climate coverage?

McKibben: I just don’t think there’s any substitute for joining together with others in movements large enough to actually make change. When we build movements, one of the things we do is help change the zeitgeist—people’s ideas of what’s normal and natural and obvious. And the media is a creature of the zeitgeist. So if we change the first, we will begin to change the second. And as you’ve doubtless seen, there’s now a lot of great reporting going on about climate change. Stuff that didn’t exist five years ago, or 10 years ago. The Times and the Post and everyone else have big climate desks and people doing truly extraordinary reporting. And I hope that extends to the cast of political reporters as well.

McKenzie: Back to how we began the conversation: By some metrics, possibly the most important ones, the climate movement has already failed. I mean, if you’re looking at it truly pessimistically. And then, if and when the political system fails, if you assume it hasn’t happened already, what then? How does activism change in the face of obstinate political inertia?

McKibben: The problem, of course, is diagnosing the point at which things have failed. Because we failed to prevent at this point about a degree-and-a-half Celsius of warming. And that’s having huge consequences. The next question is, will we fail to prevent two degrees or three degrees Celsius, which will have consequences that make this look small by comparison? And so our job is to keep building movements as big and as fast as we can, in order to prevent as much damage as we can.

But I don’t think there’s some alternative. I mean, I don’t really know what else we would do. There are people who say we should now engage in sabotage, and military, paramilitary action and things. But, you know, (a) it’s not my thing, and (b) in a world where the authorities have most of the guns, it doesn’t strike me as strategically very smart, either.

McKenzie: Can we talk a little more about global dynamics and partnerships?

McKibben: The same dynamics are underway around the world. Most places, it’s a fight to see if we can speed up the deployment of renewable energy. In some ways that is happening. We’re now installing about a gigawatt of solar power a day. That’s roughly the equivalent of a nuclear power plant worth of solar power every day. About half of that’s in China.

Some of the places very much in question that will be key to the outcome are elsewhere in Asia, which makes sense because that’s where 60 percent of our brothers and sisters live on this planet. India is crucial, and so are places like Malaysia and Vietnam and Indonesia, and how fast they can move to take advantage of their excellent solar resources will have a lot to do with how high the temperature rises. And part of that means that we have to figure out ways to move more—too much of the world’s money is in the North. And most of the stuff that really needs to get done is in the South.

I’m not optimistic about the idea that the US or anyone else—except the Norwegians—is just going to fork it over, in terms of foreign aid. I don’t hold out a huge prospect for that. It doesn’t seem to me that’s likely to be high on Mitch McConnell’s to do list. But I do think that there are lots of ways to figure out how to get much more investment flowing North to South. And I think probably the most important of those involve using the multilateral development banks, the World Bank, the IMF, things like that, to take the risk out of those investments. So that, you know, if you’re in Senegal and want a solar farm, you don’t have to pay 17 percent interest for the money to do it. You can get reasonable financing.

McKenzie: Now, that seems like a lever that’s hard for, you know, little ol’ me to pull on.

McKibben: Not that hard, in fact. People are beginning to pull on it. The movement mounted quite a successful campaign in the last year to get rid of the president of the World Bank, and replace him with someone rational, precisely on these grounds, and we won that fight. We’ll see how well it plays out and how fast they move. But it was a pretty good fight with a lot of people engaged in it. You know, he—the president of the World Bank—helped by kind of outing himself as a climate denier, which made it easier to go after him. But truthfully, these are institutions that a relatively small number of people campaigning on can have a huge effect on, because they’re kind of hidden and normally don’t get much attention.

McKenzie: One thing that’s interested me is how the idea around personal sacrifice and individual change—creature comforts—has shifted. There is a greater understanding now of how small an individual’s responsibility for the climate crisis is compared to corporations. But to what degree is sacrifice happening on a cultural level? Like this idea that more money should flow from the North to the South, or from the rich to the poor.

McKibben: If you sell it in terms of a sacrifice or a donation or something, I doubt it will happen on the scale that we need. You know, most of the money in the North is tied up in pension funds. That’s where it mostly lives. You can’t tell people, “no, you’re not going to have your retirement savings that you counted on.” But you can make it much easier for those to be invested doing things that make sense, that are necessary—mandatory for the world at this point.

In terms of just kind of sacrifice in general, I think you’re right, I think that the story has changed a little bit with the advent of super cheap, renewable energy. Like there’s certain things that it doesn’t make sense to do, like fly long distances just to get someplace where it’s a little warmer for a week or whatever. But there’s no reason you can’t have lights and run them off a solar panel. I mean, it’s an extraordinary gift, the idea that the sun is there and will happily deliver your energy for free when it rises above the horizon in the morning. And if we organized our society to do that, we could spread a lot of the things that we take for granted in the West to the rest of the world without destroying our environment in the process.

McKenzie: So if individuals are new to movement organizing, what is your suggestion for finding finding the right space for them? I mean, there’s a lot of climate groups.

McKibben: Find some place that you’re comfortable. The Sunrise Movement is great; it’s for people under 30. And they do fantastic work. Friday’s for the Future is for high school kids. And then for old people like us, Third Act is a really good route. But the point is, then we have to figure out how to cooperate with each other, to make it more than the sum of its parts. And I think we’re getting pretty good at that, assembling coalitions to do things like take on these banks and stuff has been a lot of fun.

McKenzie: Do you have any last thoughts that you would like to end on?

McKibben: I think it would be nice if we knew that if we did all the things we should do that we’ll win this fight. And I think people have had some of that comforting thought sometimes in other things.

Dr. King used to end speeches by saying the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice, which I think translates to, this may take a while, but we’re going to win. The arc of the physical universe is short, and it bends toward heat. And if we don’t win soon, we won’t win. Which is why the urgency level is so high. I wish I could provide some comforting statement like that. All I can say is this is a drama whose final act we do not know yet. And it largely depends on how many of us do how much work to change the political equation as fast as we can.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: 2024 election, climate crisis, energy politics, environmental activism, fossil fuels, global warming, media, movements

Topics: Climate Change

Bill, you have to be careful saying things like forest fires emitting several times more CO2 tan the country does from industry and vehicles. Most (70-80%) of the carbon sequestered by trees lies in the trunks. In the aftermath of a wildfire, many of those trunks are left standing. It is still possible for a caring forestry industry to harvest those trunks for lumber, thus securing that carbon for many more decades or centuries.