Virtual Tour: Turn Back the Clock

Stanley Kubrick’s doomsday machine and ‘Dr. Stangelove’

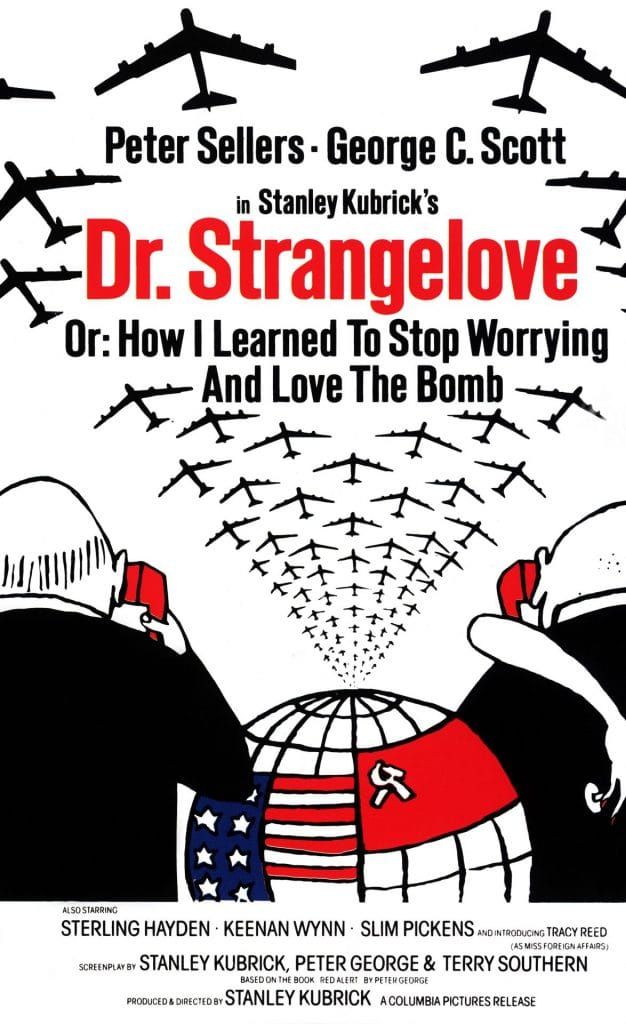

Poster for Stanley Kubrick's "Dr. Strangelove"

Poster for Stanley Kubrick's "Dr. Strangelove"

In 1960, as nuclear-armed B-52 bombers continuously flew on high alert above the U.S., film director Stanley Kubrick read about "Red Alert," an intriguing novel reviewed in the Bulletin.

“Red Alert,” the Bulletin declared, is “one of the niftiest little analyses” of real-world nuclear strategy “to come along.”

Red Alert inspired Kubrick to make “Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb” (1964), a dark comedy about all-out war triggered by human folly. Kubrick’s irreverent approach helped millions of viewers to confront their fears, and to talk and think about the unthinkable.

Kubrick’s dark satire “Dr. Strangelove” is about a psychotic U.S. Air Force general who deliberately sets off nuclear war. In the film, American leaders are unable to reverse the fictional General Jack D. Ripper’s order to bomb Russia. Russian leaders, meanwhile, can’t deactivate their “doomsday machine,” a giant bomb that automatically explodes when incoming missiles are detected. Each side follows the logic of mutually assured destruction; neither can prevent a global catastrophe.

“The most realistic things are the funniest. Laughter can only make people a little more thoughtful,” Kubrick said in 1964.

Powerful, zany and perfectly in sync with the times, “Dr. Strangelove” quickly caught fire in the public’s imagination. Its influence even extended to the 1964 presidential election.

While “Dr. Strangelove” played in U.S. movie theaters, U. S. President Lyndon B. Johnson ran for re-election. Earlier in the campaign, his opponent Barry Goldwater suggested using low-yield nuclear weapons to defoliate forests and destroy supply lines in the war against North Vietnam.

In response, Johnson framed the election as a vote about nuclear policy and highlighted Goldwater’s views in campaign ads. Suddenly, voters began to view Goldwater in a much darker light, and Johnson won by one of the biggest landslides in U.S. history.

This artifact is featured in our virtual Turn Back the Clock tour. Take the tour to learn more about the history of the Doomsday Clock and discover how you, today, can help “turn back the Clock.” Start here.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Dr. Strangelove, Virtual Tour, stanley kubrick

Take the virtual tour

This artifact is featured in our virtual Turn Back the Clock tour, based on an all-ages exhibit presented by the Bulletin at the Museum of Science and Industry from 2017 to 2019. Enter the tour to learn more about the history of the Doomsday Clock and what it says about evolving threats to humanity. See why Doomsday Clock matters more than ever and discover how you, today, can help “turn back the Clock.”