Chinese nuclear weapons, 2025

By Hans M. Kristensen, Matt Korda, Eliana Johns, Mackenzie Knight | March 12, 2025

Chinese nuclear weapons, 2025

By Hans M. Kristensen, Matt Korda, Eliana Johns, Mackenzie Knight | March 12, 2025

The modernization of China’s nuclear arsenal has both accelerated and expanded in recent years. In this issue of the Nuclear Notebook, we estimate that China now possesses approximately 600 nuclear warheads, with more in production to arm future delivery systems. China is believed to have the fastest-growing nuclear arsenal among the nine nuclear-armed states; it is the only Party to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons that is significantly increasing its nuclear arsenal. The Nuclear Notebook is researched and written by the staff of the Federation of American Scientists’ Nuclear Information Project: director Hans M. Kristensen, associate director Matt Korda, and senior research associates Eliana Johns and Mackenzie Knight.

This article is freely available in PDF format in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ digital magazine (published by Taylor & Francis) at this link. To cite this article, please use the following citation, adapted to the appropriate citation style: Hans M. Kristensen, Matt Korda, Eliana Johns, and Mackenzie Knight, Chinese Nuclear Weapons, 2025, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 81:2, 135-160, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00963402.2025.2467011

To see all previous Nuclear Notebook columns in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists dating back to 1987, go to https://thebulletin.org/nuclear-notebook/.

Within the past five years, China has significantly expanded its ongoing nuclear modernization program by fielding more types and greater numbers of nuclear weapons than ever before. Since our previous edition on China in May 2024, China has continued to develop its three new missile silo fields for solid-fuel intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), continued the construction of new silos for its liquid-fuel DF-5 ICBMs, has been developing new variants of ICBMs and advanced strategic delivery systems, and has likely produced excess warheads for these systems once they are deployed. China has also further expanded its dual-capable DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missile force, which appears to have completely replaced the medium-range DF-21 in the nuclear role. At sea, China has been refitting its Type 094 ballistic missile submarines with the longer-range JL-3 submarine-launched ballistic missile. In addition, China has recently reassigned an operational nuclear mission to some of its bombers with an air-launched ballistic missile that might have nuclear capability. In all, China’s nuclear expansion is among the largest and most rapid modernization campaigns of the nine nuclear-armed states.

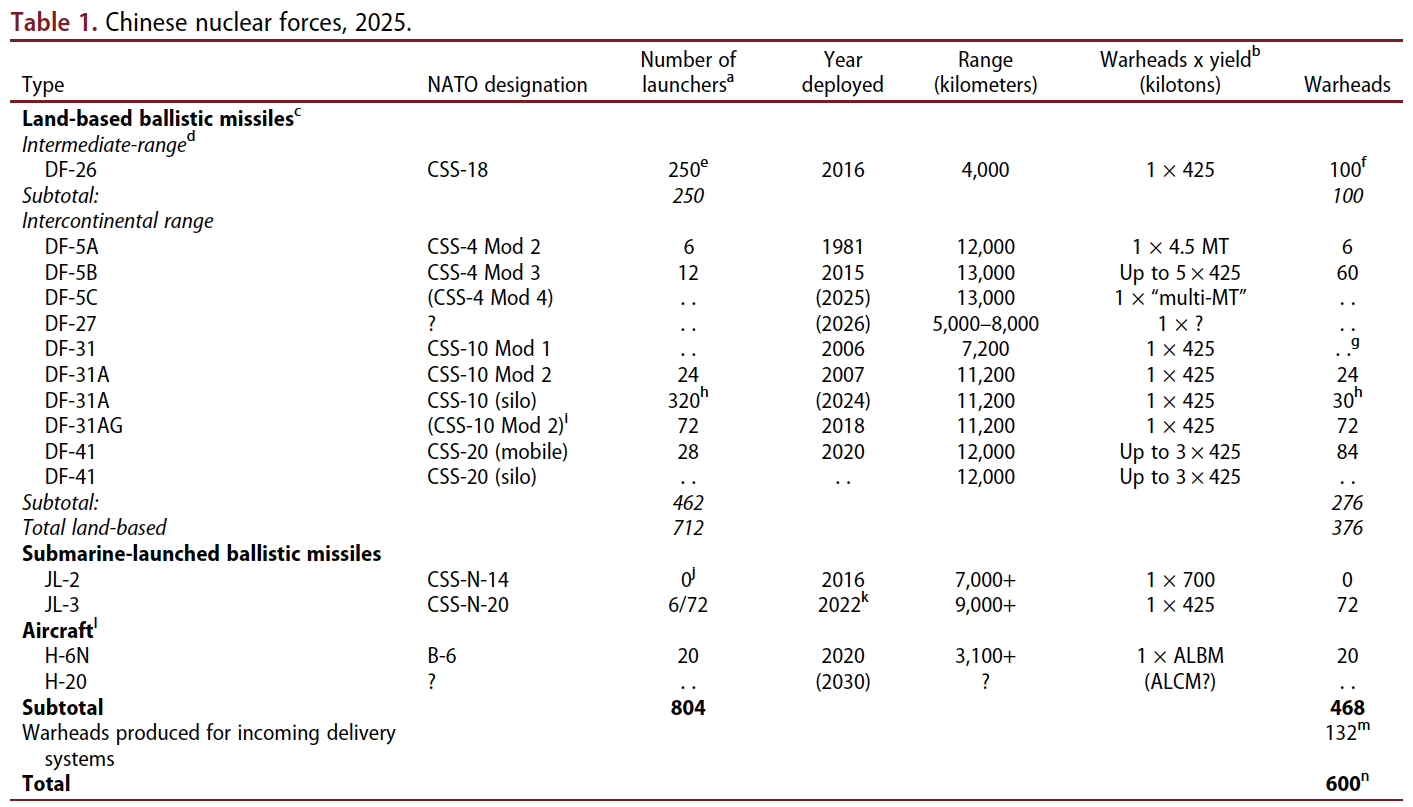

We estimate that China has produced a stockpile of approximately 600 nuclear warheads for delivery by land-based ballistic missiles, sea-based ballistic missiles, and bombers (see Table 1).

The Pentagon reported in 2024 that China’s nuclear stockpile had “surpassed 600 operational warheads as of mid-2024” (US Department of Defense 2024, IX). But Chinese warheads are not “operational” like the US and Russian nuclear warheads deployed on operational missiles and at bomber bases; nearly all Chinese warheads are thought to be stored separate from the launchers. Moreover, we cannot replicate the warhead estimate based on the reported and observable force structure unless we assign warheads to a significant number of China’s new silos.

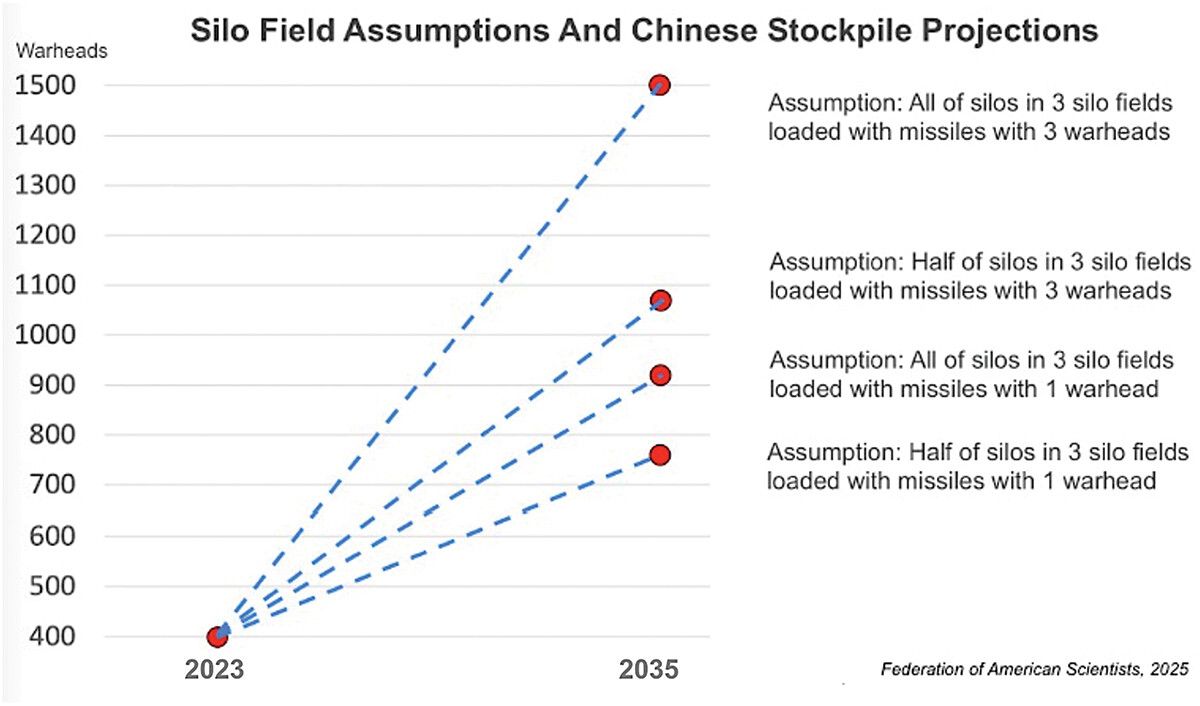

The Pentagon also estimates that China’s arsenal will surpass 1,000 warheads by 2030, many of which will probably be “deployed at higher readiness levels” (US Department of Defense 2024, IX). The Pentagon’s 2024 report to Congress, like in 2023, notably did not include the projection made in previous Department of Defense reports that China might field a stockpile of about 1,500 nuclear warheads by 2035 (US Department of Defense 2022b, 94, 98).

These projections depend on many uncertain factors, including:

- How many missile silos China will ultimately build;

- How many silos China will load with missiles;

- How many warheads each missile will carry;

- How many DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missiles will be deployed and how many of them will have a nuclear mission;

- How many ballistic missile submarines China will field and how many warheads each missile will carry;

- How many bombers China will operate and how many weapons each will carry; and

- Assumptions about the future production of fissile materials and the number of warheads China will be able to produce.

The latest Pentagon projection appears to simply apply the same growth rate of new warheads added to the stockpile between 2019 and 2021 to the subsequent years until 2030. Using that same growth rate until 2035 produces the 1,500 warheads the Pentagon previously projected. We assess that this projected growth trajectory is feasible but depends significantly upon answers to the above questions (Figure 1).

Research methodology and confidence

The analyses and estimates made in the Nuclear Notebook are derived from a combination of open sources: (1) state-originating data (e.g. government statements, declassified documents, budgetary information, military parades, and treaty disclosure data); (2) non-state-originating data (e.g. media reports, think tank analyses, and industry publications); and (3) commercial satellite imagery. Because each of these sources provides different and limited information that is subject to varying degrees of uncertainty, we crosscheck each data point by using multiple sources and supplementing them with private conversations with officials whenever possible.

Analyzing and estimating China’s nuclear forces is a challenging endeavor, particularly given the relative lack of state-originating data and the tight control of messaging surrounding the country’s nuclear arsenal and doctrine. Like most other nuclear-armed states, China has never publicly disclosed the size of its nuclear arsenal or much of the infrastructure that supports it. This degree of relative opacity makes China’s nuclear arsenal difficult to quantify, particularly given that it is likely the fastest-growing arsenal in the world. China may become more transparent about its nuclear forces over the coming decade if it deepens its participation in arms control consultations—the first of which took place in November 2023—although building a culture of nuclear transparency from scratch will take time (Gordon 2023). In September 2024, China surprisingly notified the United States before it test-launched a DF-31AG intercontinental ballistic missile from Hainan Island (Johns 2024).

Despite blind spots, it is possible to develop a much more comprehensive picture of the Chinese nuclear arsenal today than just a few decades ago by examining videos of China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) military parades, translations of strategic documents, and commercial satellite imagery. The relative degree of structure and standardization within the various PLA services also allows researchers to better understand the structure and mission of missile brigades and individual units.

Additionally, other countries—particularly the United States—regularly produce public assessments or statements about China’s nuclear forces. Such statements, however, must be verified as they can be institutionally biased and reflect a mind-set of worst-case thinking rather than the most likely scenario. Analysis produced by think tanks and non-governmental experts can also be highly useful in informing estimates: The transparency surrounding China’s missile forces, in particular, has been greatly enhanced in recent years by the unique work of Mark Stokes, Decker Eveleth (Eveleth 2023), Ben Reuter, and the US Air Force’s China Aerospace Studies Institute.

It is important to view external analysis with a critical eye, as there is a high risk of citation and confirmation bias, in which governmental or non-governmental reports build on each other’s estimates—sometimes without the reader knowing that this is occurring. This practice can inadvertently create a cyclical echo chamber effect, which may not necessarily match the reality on the ground.

In the absence of reliable or official data, commercial satellite imagery has become a particularly important resource for analyzing China’s nuclear forces. Satellite imagery makes it possible to identify air, missile, and navy bases, as well as potential underground storage facilities. For instance, satellite imagery obtained from Planet Labs, Maxar Technologies, and Copernicus was used by non-governmental experts, including some of the authors of this report, to document China’s new missile silo fields in 2021 (Korda and Kristensen 2021) and has been instrumental for continuously monitoring construction at those sites and at other bases across the country. The PLA’s standardization has also enabled researchers to better understand developments at China’s military bases, as layouts and construction dynamics now increasingly follow the same patterns, designs, and dimensions.

Considering all these factors, we maintain a relatively higher degree of confidence in our Chinese nuclear force estimates than in those of some other nuclear-armed countries where official and unofficial information is even more scarce (Pakistan, India, Israel, and North Korea). However, our estimates about Chinese nuclear forces come with relatively more uncertainty than those of countries with greater nuclear transparency (the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and Russia).

Fissile materials production

How much and how fast China’s stockpile can grow will depend upon its inventories of plutonium, highly enriched uranium (HEU), and tritium. The International Panel on Fissile Materials assessed in 2023 that China had a stockpile of approximately 14 tonnes (metric tons) of HEU and approximately 2.9 tonnes of separated plutonium in or available for nuclear weapons (Kütt, Mian, and Podvig 2023, 328–329). Those inventories were sufficient to support a doubling of the stockpile over the past five years and potentially an increase to approximately 1,000 warheads by the turn of the decade. However, producing more than 1,000 additional warheads by 2035 would require additional fissile material production; the Pentagon confirmed this assessment in 2024 by saying China “probably will need to begin producing new plutonium this decade to meet the needs of its expanding nuclear stockpile” (US Department of Defense 2024, 107). The Pentagon also assesses that China is expanding and diversifying its capability to produce tritium (108), and China reportedly began in 2023 to operate two large new centrifuge enrichment plants-one at Emeishan and another at Lanzhou (Zhang 2023a, 2023b).

Chinese production of weapon-grade plutonium reportedly ceased in the mid-1980s (Zhang 2018), and the Pentagon stated in 2024 that China “has not produced large quantities of plutonium for its weapons program since the early 1990s” (US Department of Defense 2024, 107). However, Beijing is combining its civilian technology and industrial sector with its defense industrial base to leverage dual-use infrastructure (US Department of Defense 2023, 28). It is believed that China likely intends to acquire significant stocks of plutonium by using its civilian reactors, including two commercial-sized CFR-600 sodium-cooled fast-breeder reactors that are currently under construction at Xiapu in Fujian province (Jones 2021; von Hippel 2021; Zhang 2021b). Rosatom—Russia’s state-controlled nuclear energy company—completed the final delivery of fuel to supply the first fuel loading in December 2022 (Rosatom 2022), and steam possibly seen emanating from a cooling tower on satellite imagery in October 2023 suggests the first CFR-600 reactor may have begun operation (Kobayashi 2023). In December 2023, the International Panel on Fissile Materials reported that the first reactor had begun operating at low-power mode in mid-2023 (Zhang 2023a). As of the end of 2024, it was unclear if the reactor had been connected to the grid and begun generating electricity (Park 2024). The second reactor is scheduled to come online by 2026.

To extract plutonium from its spent nuclear fuel, China completed construction of its first civilian “demonstration” reprocessing plant at the China National Nuclear Corporation (CNNC) Gansu Nuclear Technology Industrial Park in Jinta, Gansu province, which is expected to be operational in 2025 (Zhang 2024). China has started the construction of a second plant to reprocess spent light-water reactor fuel at the same location, which is expected to be up and running before the end of the decade (Zhang 2021a, 2024). Construction of a third plant in a new, extended area of the park began in 2023 and is expected to be completed in the early 2030s (Zhang 2024). The MOX plant and fuel reprocessing capacity at Jinta and the 50 tonne-per-year capacity at Jiuquan (Plant 404) could support the two CFR-600 reactors, which will begin operation with highly enriched uranium (HEU) rather than mixed oxide (MOX) fuel through a supply agreement with Russia (US Department of Defense 2023, 109; Zhang 2021a).

The ambiguity of Chinese nuclear warhead types and uncertainty on the exact amount of fissile material required for each warhead design make it difficult to estimate how many weapons China could produce from its existing HEU and weapons-grade plutonium stockpiles. If both fast-breeder reactors operate as planned (despite other countries having serious difficulties operating fast-breeder reactors), they could potentially produce large amounts of plutonium and, by some estimates, could enable China to acquire over 330 kilograms of weapon-grade plutonium annually for new warhead production (Kobayashi 2023)—which would be consistent with the Pentagon’s most recent projections (US Department of Defense 2024, 107). China, however, insists that its CFR-600 reactors are for civilian use only, and some experts have pointed out that fast-breeder reactors are an extremely inefficient way of producing weapons-grade plutonium (Park 2024).

Although China’s production and reprocessing of fissile materials is largely consistent with its nuclear power efforts and its goal of reaching a closed nuclear fuel cycle, the Pentagon asserts that Beijing intends to use this infrastructure “to produce nuclear warhead materials for its military in the near term” (US Department of Defense 2024, 107). The degree of transparency surrounding China’s nuclear materials production and its suspected expansion of uranium and tritium production has recently decreased as China has not reported its separated plutonium stockpile to the International Atomic Energy Agency since 2017 (US Department of Defense 2024, 108).

US estimates and assumptions about Chinese nuclear forces

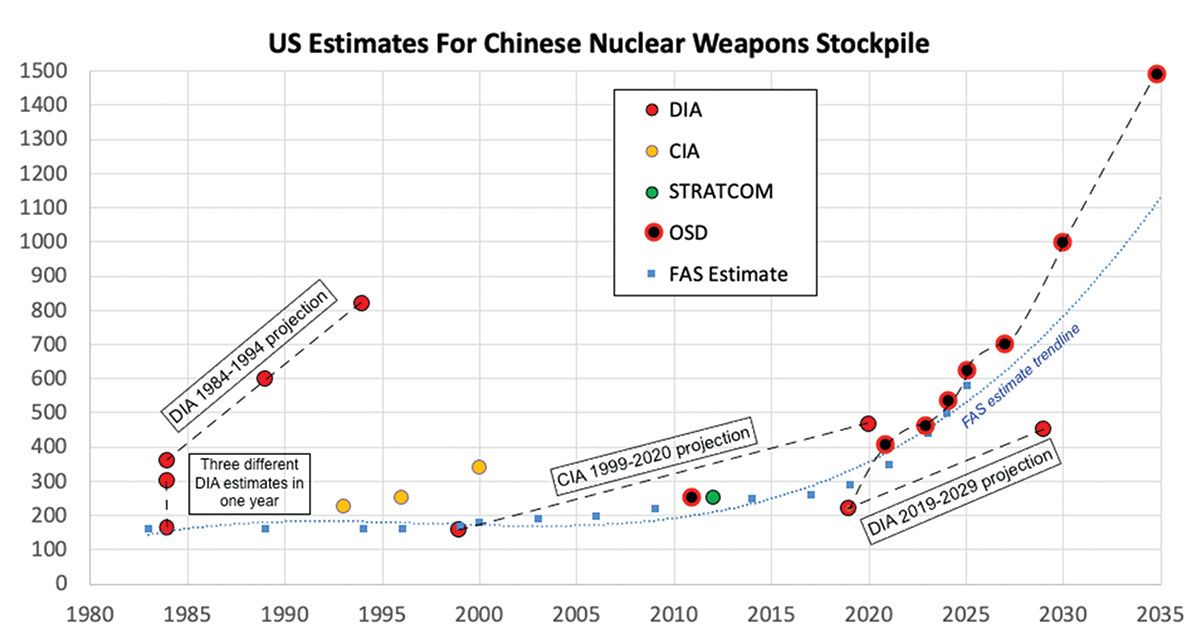

Evaluation of current US projections about the future size of China’s nuclear weapons stockpile must take earlier projections into account, some of which did not come to pass. During the 1980s and 1990s, US government agencies published several projections for the number of Chinese nuclear warheads. A US Defense Intelligence Agency study from 1984 inaccurately estimated that China had 150 to 360 nuclear warheads and projected it could increase to more than 800 by 1994 (Kristensen 2006). Over a decade later, another Defense Intelligence Agency study published in 1999 projected that China might have over 460 nuclear weapons by 2020 (US Defense Intelligence Agency 1999). While this latter projection ultimately proved to be closer to the warhead estimate the Pentagon published in 2020, it was still more than twice the “low-200s” warhead estimate announced by the Pentagon (US Department of Defense 2020, ix; Figure 2).

Current US projections also come with significant uncertainties. In November 2021, the Pentagon’s annual China Military Power Report (CMPR) to Congress projected that China could have 700 deliverable warheads by 2027, and possibly as many as 1,000 by 2030 (US Department of Defense 2021, 90). The 2022 Pentagon report increased the projection even further, claiming that China’s stockpile of “operational” nuclear warheads had surpassed 400 and might reach about 1,500 warheads by 2035 (US Department of Defense 2022b, 94). The estimate increased to more than 500 warheads in 2023 and to over 600 warheads in 2024 and repeated the projection that China might possess over 1,000 operational warheads by 2030 (US Department of Defense 2024, IX). However, the available public information and observable force structure do not allow us to replicate the estimate of more than 600 warheads unless we assign a significant number of nuclear warheads—up to 160—to the new silos. As a result, we assess that China’s stockpile number might include approximately 600 warheads but that this estimate must include a significant number of warheads that have been produced to eventually arm missiles that are still in the process of being fielded.

Chinese officials have pushed back against what they see as the “sensationalized” or “exaggerated” claims made in successive Pentagon CMPRs (Li 2022a; Ministry of National Defense of the People’s Republic of China 2023a). However, the Chinese government has not denied—and has barely acknowledged—the expansion of the mobile ICBM force or the construction of three large new missile silo fields.

The projected increase has unsurprisingly triggered a wide range of speculations about China’s nuclear intentions. Over the past five years, high-ranking US officials—including the former US STRATCOM commander—have suggested that China has moved away from its longstanding “minimum deterrence” posture, and that it “seeks to match, or in some areas surpass, quantitative and qualitative parity with the United States in terms of nuclear weapons” (Billingslea 2020; Bussiere 2021; US Strategic Command 2022; Cotton 2023).

US officials and individuals in the public debate have repeatedly claimed that China’s expansion will make it a nuclear “peer” or “near peer” in the future. This is a gross exaggeration, however: There is no evidence that China’s ongoing nuclear expansion will result in parity with the US arsenal. Even the worst-case 2023 projection of 1,500 warheads by 2035 amounts to less than half of the current US nuclear stockpile. When reminded about that reality, some US defense officials have sought to downplay the importance of numbers: “We don’t approach it from purely a numbers game,” according to then-deputy commander of the US Strategic Command, Lt. Gen. Thomas Bussiere. “It is what is operationally fielded, … status of forces, posture of those fielded forces. So, it is not just a stockpile number,” he said (Bussiere 2021).

Nuclear testing

The projection for how much the Chinese nuclear stockpile will increase also depends on the size and design of its warheads. China’s nuclear testing program of the 1990s partially supported the development of the warhead (#535) type currently arming the DF-31-class ICBMs. This warhead design may also have been used to equip the liquid-fueled DF-5B ICBM with multiple independently targeted reentry vehicle (MIRV) technology, replacing the much larger multi-megaton warhead (#506) used on the DF-5A. The large DF-41 and the JL-3 missiles could potentially use the same smaller #535 warhead or the even smaller #5×5 warhead (Zhang 2025). The Pentagon believes that China probably seeks a “lower-yield” nuclear warhead for the DF-26 (US Department of Defense 2024, 124); however, it is unclear if that implies the production of a new warhead or how low such a “lower” yield might be. China is thought to already have a lower-yield warhead, the #5×5 warhead (Zhang 2025). For instance, if Beijing wanted a low-yield warhead, it could potentially do so by using existing warheads and “turning off” the uranium secondary so only smaller-yield plutonium primary is used, similarly to what the United States did with its W76–2 warhead more than five years ago.

Developing significantly different warhead designs would probably require additional nuclear test explosions. To avoid such tests, China could potentially make simpler designs that use a previously tested nuclear explosive package, advanced computer simulations, and sub-critical (or very low-yield) underground explosive experiments. Recently, the United States has claimed that some of China’s actions at Lop Nur “raise concern” about its adherence to the United States’ “zero-yield” standard (US Department of State 2022, 29). However, the report did not explicitly accuse China of conducting critical tests that produced a yield, and none of the 2023 and 2024 Compliance Reports included any additional information. Instead, the State Department and Pentagon suggested that the activities at Lop Nur are an indication that China might be planning to use the site “year-round” (US Department of State 2023, 18; 2024; US Department of Defense 2024).

Analysis of commercial satellite imagery shows significant construction at the Lop Nur site with the construction of approximately a dozen concrete buildings near the site’s airfield, as well as at least one new tunnel at the site’s northern testing area (Brumfiel 2021b). The imagery shows what appears to be new drainage areas, drill rigs, roads, spoil piles, and covered entrances to potential underground facilities, as well as new construction at the main administration, support, and storage areas (Babiarz 2023; Brumfiel 2021a; J. Lewis 2023). Many of these activities appeared to still be ongoing as of the time of writing this report. In addition to new activity at the northern tunnel test area, satellite imagery also indicated activity at a possible new eastern test area at Lop Nur (Babiarz 2023). However, although the construction works are significant, they do not prove that China plans to conduct new nuclear explosive tests at the site. Should China conduct low-yield nuclear tests at Lop Nur, it would violate its responsibility under the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty it has signed but not ratified.

Nuclear doctrine and policy

Since its first nuclear test in 1964, China has maintained a consistent narrative about the purpose of its nuclear weapons. This narrative was restated in China’s updated 2023 national defense policy:

China is always committed to a nuclear policy of no first use of nuclear weapons at any time and under any circumstances, and not using or threatening to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear-weapon states or nuclear-weapon-free zones unconditionally. … China does not engage in any nuclear arms race with any other country and keeps its nuclear capabilities at the minimum level required for national security. China pursues a nuclear strategy of self-defense, the goal of which is to maintain national strategic security by deterring other countries from using or threatening to use nuclear weapons against China. (Ministry of National Defense of the People’s Republic of China 2023b)

China increasingly refers to its nuclear forces as a key capability for achieving “strategic counterbalance”—a phrase that has not been formally defined by Chinese government sources—which appears to suggest that China believes its nuclear weapons play a role in shaping the geostrategic balance of global power (Zhao 2024).

Despite its declaratory policy of emphasizing a “defensive” nuclear posture, China has never defined how large a “minimum” capability is or what activities constitute an “arms race.” The stated policies evidently do not prohibit the unprecedented expansion of China’s nuclear arsenal currently underway. The posture apparently seeks to “adapt to the development of the world’s strategic situation,” part of which involves the “organic integration [of] nuclear counterattack capability and conventional strike capability” (China Aerospace Studies Institute 2022, 381–382).

Such capabilities require investing significant resources to ensure the survivability of the nuclear arsenal against a nuclear or conventional first strike, including practicing “nuclear attack survival exercises” to ensure that troops could still launch nuclear counterattacks if China were to be attacked (Global Times 2020). It also involves improving early-warning systems and the stealth capabilities of its nuclear forces to be able to elude enemy detection (Kaufman and Waidelich 2023, 42, 45).

The People’s Liberation Army maintains what it refers to as a “moderate” readiness level for its nuclear forces and keeps most of its warheads at its regional storage facilities and its central hardened storage facility in the Qinling mountain range.[1] The 2024 Pentagon report reaffirmed this posture, stating that China maintains “a portion of its units on a heightened state of readiness while leaving the other portion in peacetime status with separated launchers, missiles, and warheads.” But the report also described that the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF) brigades conduct “combat readiness duty” and “high alert duty” drills, which “includes assigning a missile battalion to be ready to rapidly launch” (US Department of Defense 2024, 106).

The readiness of the Chinese nuclear missile force was challenged in early 2024 with the disclosure that a US intelligence assessment had found that corruption within the People’s Liberation Army had led to an erosion of confidence in its overall capabilities, particularly when it comes to the Rocket Force (Martin and Jacobs 2024). The 2024 Pentagon report noted that the subsequent corruption investigation “likely resulted in the PLARF repairing the silos, which would have increased the overall operational readiness of its silo-based force” (US Department of Defense 2024, 159). This could explain the heightened activity seen through satellite imagery at several new Chinese silos over the past year.

Increased readiness and alert drills do not necessarily require nuclear warheads to be installed on the missiles or prove that they are installed at all times, but it cannot be ruled out either. However, recent dismissals of top defense officials and widespread corruption might degrade the Chinese leadership’s willingness to arm missiles with warheads in peacetime.

A nuclear attack against China is unlikely to come out of the blue and is more likely to follow a period of increasing tension and possibly conventional warfare, allowing the warheads to be mated to the missiles in time. Moreover, a credible retaliatory capability doesn’t require missiles to be on alert in peacetime: With launchers inside tunnels dispersed across vast mountainous areas, it is impossible—even for a large nuclear adversary—to prevent China from retaliating with at least some of its missiles intact. In April 2019, the Chinese delegation to the Preparatory Committee for the 2020 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons provided a generic description of its alert posture and the stages Chinese nuclear forces would go through in a crisis:

In peacetime, the nuclear force is maintained at a moderate state of alert. In accordance with the principles of peacetime-wartime coordination, constant readiness, and being prepared to fight at any time, China strengthens its combat readiness support to ensure effective response to war threats and emergencies. If the country faced a nuclear threat, the alert status would be raised and preparations for nuclear counter-attack undertaken under the orders of the Central Military Commission to deter the enemy from using nuclear weapons against China. If the country were subjected to nuclear attack, it would mount a resolute counter-attack against the enemy (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China 2019).

In peacetime, the “moderate state of alert” might involve designated units to be deployed in high combat-ready condition with nuclear warheads installed, or in nearby storage sites under the control of the Central Military Commission that could be released to the unit quickly if necessary. Analysts have described Chinese nuclear forces as following a six-stage alert sequence based upon increasingly actionable intelligence (J. W. Lewis and Xue 2012; Wood, Stone, and Corbett 2024):

- Standing war preparedness alert: day-to-day readiness condition.

- Class 3 operational preparations alert: missile bases accelerate preparations for launching missiles and base security is upgraded.

- Class 2 operational preparations alert: missile bases, including associated air defense and ground crews, shift to maximum readiness.

- Class 1 operational preparations alert: gives authority to designated base commanders to launch nuclear weapons upon receipt of formal orders from the Central Military Commission.

- Preparatory order: includes precise timing and instructions for mobile launch units to enter launch sites and for siloed units to conduct necessary pre-launch activities.

- Formal order: official launch order from the Central Military Commission authorizing the use of nuclear weapons.

China is building several underground facilities at some of its newer sites, including at its three solid-fuel missile silo complexes, which could potentially be used for warhead storage. Each PLARF regional base has a dedicated “equipment inspection” regiment or brigade that is responsible for storage, management, and transportation of the nuclear weapons assigned to missile brigades in that base area.

The Pentagon assesses that the construction of hundreds of new silos for quick-launch solid fuel missiles and development of a space-based early warning system indicate China’s intent to move to a launch-on-warning (LOW) posture, known in China as a “early warning counterstrike” (预警反击), giving China time to launch its missiles before they would be destroyed (US Department of Defense 2024, 110). The Pentagon says that China “likely has at least three early warning satellites in orbit” and that the PLARF continues to conduct exercises involving “early warning of a nuclear strike and LOW responses” (110).

In addition to the technical means for protecting the missiles against a first strike, the PLARF has also emphasized “survival protection” for its land-based nuclear forces (China Aerospace Studies Institute 2022, 386). This involves training soldiers to perform additional tasks beyond their primary roles, including a “role switch” where a transporter erector launcher (TEL) driver would also know how to launch a missile, or a measurement specialist who knows how to command (Baughman 2022). During one “survival protection” training exercise in November 2021, a launch battalion was informed they would be “killed” by an enemy missile strike in five minutes. Rather than attempting to evacuate—the standard “survival protection” procedure—the battalion commander ordered his troops to conduct a surprise “launch on the spot” of their ballistic missile before the enemy missile hit their position (Baughman 2022; Lu and Liu 2021). While the report did not specify whether the battalion had a nuclear or conventional strike role, the exercise suggests that the PLARF is practicing launching missiles in a launch-on-warning scenario.

These data points, however, are not necessarily evidence of a formal shift to a more aggressive nuclear posture (Fravel, Hiim, and Trøan 2023). They could just as likely be intended to allow China to disperse its forces and, if needed, launch rapidly—but not necessarily “on warning”—in the context of a crisis, thereby safeguarding its forces against a surprise conventional or nuclear first strike. For decades, China has deployed silo-based DF-5s and road-mobile ICBMs that, in a crisis, would be armed with the intention to launch them before they are destroyed. China potentially could maintain its current strategy even with many new silos and improved early-warning systems.

Notably, both the United States and Russia operate large numbers of solid-fuel silo-based missiles and early-warning systems to be able to detect nuclear attacks and launch their missiles before they are destroyed. The two countries also insist that such a posture is both necessary and stabilizing. It seems reasonable to assume that China would seek a similar posture to safeguard its own retaliatory capability.

A Chinese early-warning system could potentially also be intended to enable a future advanced missile defense system. The latest Pentagon report on China’s military capabilities notes that China is fielding an indigenous HQ-19 (known to the United States as CH-AB-02) anti-ballistic missile system and developing an “ultra-long-range” missile defense system as well as hit-to-kill mid-course technology that could engage intermediate-range ballistic missiles and possibly ICBMs, although the latter would still take many years to develop (US Department of Defense 2024, 62). China already maintains several ground-based large phased-array radars that contribute to its nascent early-warning capabilities.

China’s nuclear expansion and apparent pursuit of a launch-on-warning capability have triggered a debate about China’s longstanding no-first-use policy. Although there has been considerable discussion in China about the size and readiness of the nuclear arsenal as well as when the no-first-use policy would apply, there is little evidence to suggest that the Chinese government has deviated from it, which is also reiterated in its 2023 national defense strategy (Ministry of National Defense of the People’s Republic of China 2023b; Santoro and Gromoll 2020).

As with other nuclear-armed states, there is uncertainty and ambiguity about what circumstances could cause the Chinese leadership to order the use of nuclear weapons. Despite its no-first-use policy, Chinese officials have privately stated in the past that China reserves the right to use nuclear weapons if its nuclear forces were attacked with conventional weapons. The Pentagon echoed this in its 2024 report: “China’s nuclear strategy probably includes consideration of a nuclear strike in response to a non-nuclear attack threatening the viability of China’s nuclear forces or C2, or that approximates the strategic effects of a nuclear strike” (US Department of Defense 2024, 102).

The modernization of the nuclear forces could potentially influence Chinese nuclear strategy and declaratory policy gradually in the future by offering the Chinese leadership more efficient ways of deploying, responding, and coercing with nuclear or dual-capable forces. The 2022 US Nuclear Posture Review suggested that China’s trajectory of expanding and improving its nuclear arsenal could “ … provide [China] with new options before and during a crisis or conflict to leverage nuclear weapons for coercive purposes, including military provocations against US Allies and partners in the region” (US Department of Defense 2022a, 4).

This raises the question of whether China will leverage nuclear weapons in its “counter-intervention” strategy that aims to limit the US presence in the East and South China Seas and achieve reunification with Taiwan. China has made clear that it “keeps to the stance that China will not attack unless we are attacked, but China will surely counterattack if attacked. China will firmly defend its national sovereignty and territorial integrity, and resolutely thwart the interference of external forces and the separatist activities for ‘Taiwan Independence’” (Li 2022b).

Regardless of what the specific red lines may be, China’s no-first-use policy probably has a high threshold. The significant modernization of non-nuclear forces seems to indicate that the Chinese leadership is interested in keeping it that way. Many experts believe there are very few scenarios in which China would benefit strategically from a first nuclear strike even in the case of conventional conflict with a military power such as the United States (Tellis 2022, 27). However, in a situation in which the stakes would be high—such as in a military clash over Taiwan—both China and the United States appear to reserve the option of using nuclear weapons—including first—if deemed necessary. In the Pentagon’s words: “Beijing probably would consider nuclear first use if a conventional military defeat in Taiwan gravely threatened [the Chinese Communist Party] regime survival” (US Department of Defense 2024, 102).

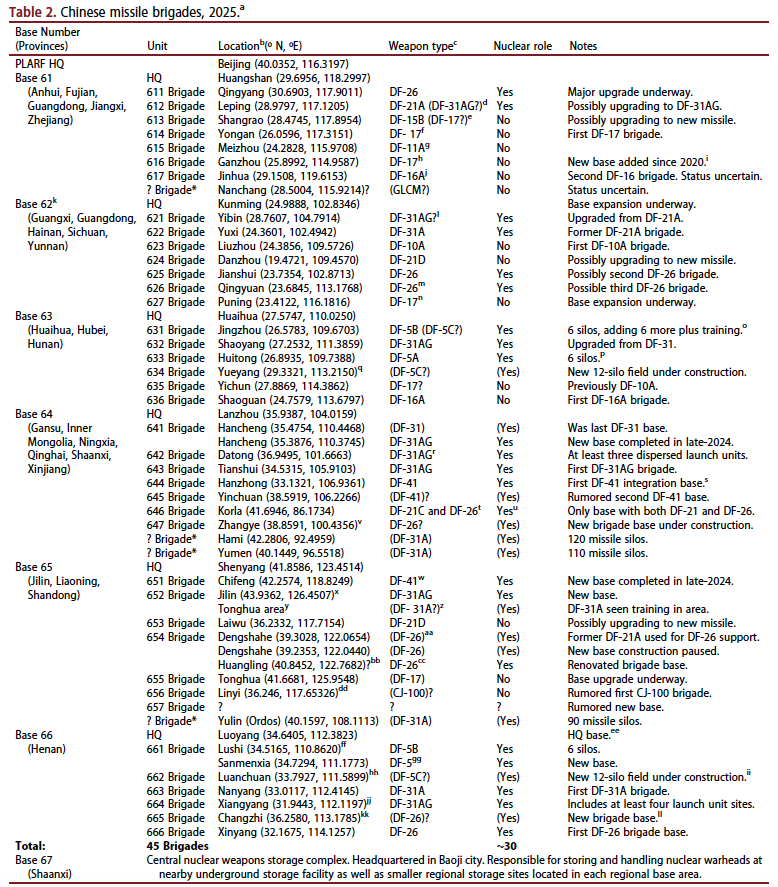

Land-based ballistic missiles

China continues the long-term modernization of its land-based, nuclear-capable missile force. But the pace and scope of this effort have increased significantly over the past few years with the construction underway of approximately 350 new missile silos and several new bases for road-mobile missile launchers. Overall, we estimate that the PLARF currently operates approximately 712 launchers for land-based missiles that can deliver nuclear warheads. But not all of those are necessarily assigned nuclear warheads. Of those launchers, 462 can be loaded with missiles that can reach the continental United States. Many of China’s ballistic missile launchers are for short-, medium-, and intermediate-range missiles intended for regional missions, and most of those do not have nuclear strike missions. We estimate that China has roughly 100 nuclear warheads assigned to regional missiles, although this number comes with significant uncertainty.

The PLARF, which is headquartered in Beijing, has recently undergone several management shakeups: In July 2023, the PLARF commander and political commissar, along with several other senior officers, were removed from their positions following an anti-corruption investigation. Notably, the top two PLARF officials were replaced by generals from outside the PLARF itself: the new commander and political commissar come from the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) and the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF), respectively (Lendon, McCarthy, and Chang 2023). In October 2023, China’s Minister of National Defense Li Shangfu, who would have been responsible for approving nuclear weapons acquisitions, was also removed from his post (US Department of Defense 2024, XII).

The PLARF controls nine individually numbered bases: six for missile operations distributed across China (Bases 61 through 66), one for overseeing the central nuclear stockpile (Base 67), one for maintaining infrastructure (Base 68), and one that is assumed to be for training and missile tests (Base 69) (Xiu 2022, 2). Each missile operating base controls six to eight missile brigades, with the number of launchers and missiles assigned to each brigade depending on the type of missile (Xiu 2022, 5).

To accommodate the growing missile force, the total number of Chinese missile brigades has increased too. This increase is predominantly caused by the growing inventory of conventional missiles, but it is also a product of China’s nuclear modernization program. We estimate that the PLARF currently has approximately 45 brigades with ballistic or cruise missile launchers. Approximately 30 of those brigades either operate ballistic missile launchers with nuclear capability or are upgrading to do so soon (see Table 2). This is close to the 50 nuclear missile brigades that Russia operates—known as regiments in the Russian military vocabulary (Kristensen, Korda, and Reynolds 2023).

Intercontinental ballistic missiles

Of China’s 462 ICBM launchers, we estimate that over 170 may have been assigned missiles that can deliver over 270 warheads. This may include some missiles loaded in three new silo fields that recently were completed in northern China, although it remains to be seen how many of the silos will be loaded. These 320 new silos for solid-fuel missiles and the construction of 30 new silos for liquid-fuel missiles in three mountainous areas of central-eastern China constitute the most significant recent development in China’s nuclear arsenal (Eveleth 2023; Korda and Kristensen 2021; Lee 2021; J. Lewis and Eveleth 2021; Reuter 2023).

At two of the three missile silo fields—as well as the training site at Jilantai—the silos are positioned roughly three kilometers apart in an almost perfect triangular grid pattern. The silos in the third field are positioned randomly but still with the same distance between them. The silo fields are located deeper inside China than any other known ICBM base, and beyond the reach of the United States’ conventional and nuclear cruise missiles. The Pentagon’s 2024 CMPR states that China “has loaded at least some ICBMs”—likely DF-31s—across the three silo fields (US Department of Defense 2024, 77, 103). We cautiously estimate that perhaps 10 silos in each missile field may have been loaded. The new silo fields are described in detail below:

Yumen silo field

The Yumen silo field, located in Gansu province in the western military district, covers an area of approximately 1,110 square kilometers with a perimeter fence surrounding the entire complex. The field includes 120 individual silos. There also appear to be at least five launch control centers scattered throughout the field, which are connected to the silos through underground cables.

In addition to the 120 silos, the Yumen field also includes dozens of supporting and defensive structures. These include multiple security gates in the north (40.38722° N, 96.52416° E) and south (40.03437° N, 96.69658° E), at least 23 support facilities, and approximately 20 surveillance or radio towers. Additionally, the Yumen field includes at least five raised square platforms around the perimeter of the complex, which could possibly be used for air and missile defense.

Construction of the field began in March 2020 and the last inflatable shelter was removed in February 2022, indicating that the most sensitive construction on each silo has now been completed. Construction at the Yumen field is the furthest along out of the three silo complexes. For some time between April and May 2024, several silos were covered with a camouflage structure to conceal possible maintenance on the silos.

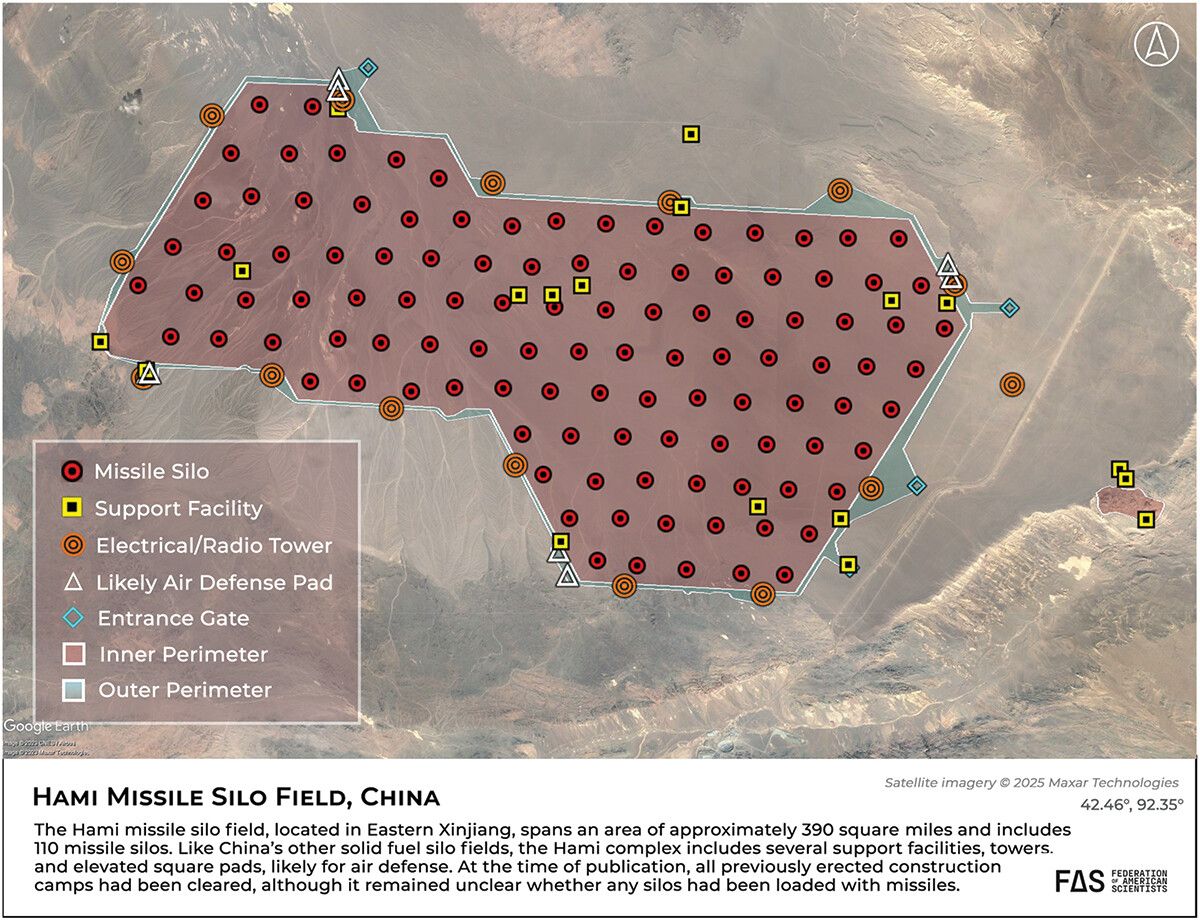

Hami silo field

The Hami field, located in Eastern Xinjiang in the western military district, spans an area of approximately 1,028 square kilometers, roughly the same size as the Yumen field, and has a similar perimeter fence around the entire complex.

Construction at the Hami field, which includes 110 missile silos, is thought to have begun at the start of March 2021—roughly one year after Yumen. The last of the Hami field’s inflatable domes were removed in August 2022, indicating the completion of the most sensitive aspects of construction.

Like Yumen, the Hami field includes at least three security gates, at least 15 surveillance or radio towers, several potential launch control centers, a rail transfer facility, and several raised square platforms for air-defense forces matching those found at the Yumen field (Figure 3). There is also a separate fenced complex—located roughly 10 kilometers from the eastern fence of the main silo field—which includes several tunnels that could potentially be intended for warhead storage.

Yulin silo field

The Yulin field, located near Hanggin Banner west of Ordos, is smaller than the other two fields, measuring 832 square kilometers. It includes 90 missile silos, at least 12 support facilities, and several suspected launch control centers and air defense sites. Unlike the Hami and Yumen fields, the Yulin field does not yet have a significant fence perimeter, although each silo is surrounded by its own secure fencing.

Construction at the Yulin field began shortly after that of the Hami field (in April or May 2021), and it has a different layout than both the Yumen and Hami fields. Unlike the other two fields, the silos at the Yulin site are positioned in a slightly less grid-like pattern, although most silos are still spaced roughly three kilometers apart. In addition, the inflatable domes erected during construction at the Yulin field were all round, as opposed to the rectangular domes found at the Yumen and Hami fields, although this is likely due to logistical or construction reasons rather than a distinct difference between the silos themselves.

Recent satellite imagery shows activity at many silos, but this could simply indicate regular maintenance.

China’s ICBM force structure

In total, these discoveries suggest that China is constructing 320 new silos for solid-fueled ICBMs across the three fields of Yumen, Hami, and Yulin, excluding the approximately 15 training silos at the Jilantai site. In addition, China is upgrading and expanding the number of silos for the liquid-fueled DF-5 ICBM and increasing the number of silos per brigade (US Department of Defense 2023, 107). This appears to include doubling the number of silos of at least two existing DF-5 brigades from six to 12 and adding two new brigades each with 12 silos. Once completed, based on current observations, this project will increase the number of DF-5 silos from 18 to 48.

Combined, these construction efforts for silo-based ICBMs (in addition to new road-mobile ICBM bases) constitute the largest expansion of the Chinese nuclear arsenal ever. The 350 new Chinese silos under construction exceed the number of silo-based ICBMs operated by Russia and constitutes about three-quarters the size of the entire US ICBM force.

In addition to the construction of new ICBM facilities, there is uncertainty about how many ICBMs China currently operates. The US Department of Defense’s (2024) report about China’s military and security developments assessed that, as of early 2024, China had 500 ICBM launchers (silo and mobile) with 400 missiles in its inventory (US Department of Defense 2024, 66). The previous reports listed 500 launchers and 350 missiles as of the end of 2022, and 300 launchers and 300 missiles as of the end of 2021 (US Department of Defense 2022b, 167; 2023, 186). The sharp increase in the number of launchers over two years suggests that the US Department of Defense is now counting all of China’s new silos in its ICBM launcher estimate. However, it is likely many of these new silos are still not loaded with missiles; the difference between 500 launchers and 400 missiles indicates that China may still be producing missiles for the new launchers. Analysis of satellite imagery shows that construction is ongoing in all three silo fields, suggesting that they may still be some years away from full operational capability.

In its 2024 report, the Pentagon assessed that China “has loaded at least some ICBMs”—likely a “DF-31-class” ICBM—into the silos at its new silo fields (US Department of Defense 2024, 63, 103).

If each silo in the three new silo fields is loaded with a single-warhead DF-31-class ICBM, the total number of warheads in China’s ICBM force could potentially be approximately 600 warheads—more than twice as many as today’s estimate of 276. However, it is currently unknown how China will operate the new silos—whether all silos will be filled; whether they will be loaded with just silo-based DF-31-class ICBMs or a mix of DF-31As and DF-41s; and how many warheads each missile will carry. (Figure 1 above shows the effect of these uncertainties on the projections of Chinese nuclear weapons.) Regardless of what missile type ends up in each silo, the sheer number of silos will likely have a significant effect on US strike plans against China because the US targeting strategy has been typically focused on holding nuclear and other military targets at risk, although this strategy does not mean that all silos must necessarily be held at risk at the same time.

At this stage, it is unclear how these hundreds of new silos will alter the existing brigade structure for China’s missile forces. Presently, each of China’s ICBM missile brigades is responsible for six to 12 launchers, and it might be expected that each new missile silo field would be organized as a single brigade. However, some analysts have hypothesized that the three new silo fields could lead to the creation of entirely new PLARF “Bases” (each with several brigades)—an extremely rare event that has not taken place in more than 50 years (Xiu 2022, 255). For now, the Pentagon’s 2024 report on China shows the Hami and Yumen missile silo fields as “Missile Brigades” in the Western Theater organized under Base 64, and the Yulin missile silo field as a “Missile Brigade” in the Northern Theater organized under Base 65 (US Department of Defense 2024, 64, 119, 121).

Although China has deployed ICBMs in silos since the early 1980s, building missile silos on this scale is a significant shift in China’s nuclear posture. The decision to do so has probably not been caused by a single event or issue but, rather, by a combination of strategic and operational objectives, including protecting the retaliatory capability against a first strike, overcoming the potential effects of adversarial missile defenses, better balancing the ICBM force between mobile and silo-based missiles, increasing China’s nuclear readiness and overall nuclear strike capability to account for improvements in the Russian, Indian, and US nuclear arsenals, elevating China to a world-class military power, as well as national prestige.

Currently two versions of the DF-5 are deployed: the DF-5A (CSS-4 Mod 2) and the MIRVed DF-5B (CSS-4 Mod 3). Since 2020, the Pentagon’s annual reports to Congress have noted that the DF-5B can carry up to five MIRVs (US Department of Defense 2020, 56), and that this version is likely being upgraded (US Department of Defense 2024, 103). We estimate that two-thirds of the DF-5s are currently equipped to carry MIRVs. In its 2024 annual report, the Pentagon indicated that a third modification with a “multi-megaton yield” warhead—known as the DF-5C—is currently being fielded and suggests that at least two brigades will likely field the DF-5C (US Department of Defense 2024, 103).

In 2006, China debuted its first solid-fuel road-mobile ICBM—the DF-31 (CSS-10 Mod 1)—which had a range of about 7,200 kilometers, meaning that it could not reach the continental United States from its deployment areas in China.[2] Since then, China has iterated on its original DF-31 design, producing newer versions of the missile: the extended-range DF-31A (CSS-10 Mod 2) and DF-31AG, which has increased maneuverability, as well as one additional silo-based variant.

There is some uncertainty about the name of the silo-based variant of the DF-31. The 2021 and 2022 CMPRs indicated the potential existence of a DF-31B ICBM, but subsequent editions did not include this designation. The Pentagon’s 2024 report stated two CSS-10 Mod 3 were launched out of a training silo in September 2023, which is different than the “DF-31-class ICBM” language that has recently been used to describe the version that is being loaded into China’s new silo fields (US Department of Defense 2024, 107). The DF-31B and the CSS-10 Mod 3 may be the same missile, although the language is unclear. As of October 2024, these newer variants were assumed to have completely replaced the original DF-31 in China’s arsenal.

The DF-31A (CSS-10 Mod 2) is an extended-range version of the DF-31. With a range of 11,200 kilometers, the DF-31As can reach most of the continental United States from most deployment areas in China. Each DF-31A brigade used to operate only six launchers but they have recently been upgraded to operate 12 (Eveleth 2020). We estimate that China still deploys a total of about 24 DF-31As in two brigades.

In his March 2023 testimony before Congress, US STRATCOM Commander Gen. Anthony Cotton surprisingly suggested that the DF-31A ICBM could carry MIRVs. This differs from the US Air Force’s National Air and Space Intel Center’s (NASIC) 2020 estimate that the DF-31As are equipped with only one warhead per missile, as well as from the Pentagon’s 2022 annual China report, which referred to the DF-41 as “China’s first road-mobile and silo-based ICBM with MIRV capability,” therefore indicating that the DF-31A is not MIRV-capable (Cotton 2023; National Air and Space Intelligence Center 2020; US Department of Defense 2022b, 94). It remains unclear whether the discrepancy can be attributed to updated intelligence, an incorrect statement by the US STRATCOM commander, or divergent assumptions by different branches of the intelligence community. It is also unclear how the DF-31 family could be MIRV-capable unless China has also designed a smaller-diameter MIRV warhead; some claim China has developed a smaller warhead with a lower yield (Zhang 2025). Adding warheads would also reduce the range of the missile due to a heavier payload. For these reasons and in the absence of further information, we continue to attribute one warhead to each DF-31A.

Since 2017, China’s road-mobile ICBM modernization effort has focused on supplementing and possibly replacing the DF-31A version with the newer DF-31AG and increasing the number of associated bases; we estimate that seven brigades operate the DF-31AG. The new DF-31AG eight-axle launcher is thought to carry the same missile as the DF-31A launcher but has improved off-road capabilities. The US Air Force NASIC’s 2020 missile report listed the DF-31AG as having an unknown (“UNK”) number of warheads per missile in contrast to the DF-31A, which was listed with only one warhead. This suggests that the AG version could potentially have a different payload (National Air and Space Intelligence Center 2020, 29). However, for the same reasons as for the DF-31A, we currently assume that the DF-31AG is also deployed with a single warhead.

The next phase of China’s ICBM modernization is the integration of the new DF-41 ICBM (CSS- 20) that began development back in the late 1990s. China displayed 18 DF-41s at its 70th National Day parade in October 2019, with the launchers being said to come from two brigades (New China 2019). In April 2021, the commander of US Strategic Command testified to Congress that the DF-41 “became operational [in 2020], and China has stood up at least two brigades” (Richard 2021, 7). A third base appears to have been completed and several other bases may be upgrading to receive the DF-41 as well. The number of garages at the bases indicates that there may be approximately 28 DF-41 launchers deployed.

In previous Nuclear Notebooks, we estimated that the DF-41 could carry up to three MIRVs, which the Pentagon’s 2023 and 2024 China reports appeared to validate (US Department of Defense 2023, 107; 2024, 104). It is unknown if all DF-41s will be equipped with MIRVs or if some will have only one warhead to maximize range. In addition to road-mobile launchers, the Pentagon says that China “appears to be considering additional DF-41 launch options, including rail-mobile and silo-basing” (US Department of Defense 2024, 65; 2022b, 65). “Silo basing” mode appears to refer to China’s new silo fields at Yumen, Hami, and Yulin.

China is also developing a new dual-capable missile, known as the DF-27 (CSS-X-24), which reportedly has a range between 5,000 and 8,000 kilometers and likely has a hypersonic glide vehicle payload option (US Department of Defense 2024, 65, 109). This range class is somewhat redundant for the nuclear strike mission, as these distances can already be easily covered by China’s longer-range ICBMs. It is therefore potentially possible that the system could ultimately be used in a conventional strike role. Reporting surrounding the DF-27 is highly unclear, however: The Pentagon’s 2024 report states that the missile may be deployed. Moreover, a US intelligence assessment of February 2023 notes that “land attack and antiship variants [of the DF-27] likely were fielded in limited numbers in 2022,” whereas in May 2023 the South China Morning Post reported that the DF-27 has been in service since 2019, citing a Chinese military source (R. Chan 2023; US Department of Defense 2023, 67). In June 2021, Chinese state media broadcasted videos of what was rumored to be a military exercise featuring the DF-27 (Tiandao 2022), which strongly resembles the DF-26 with an attached conical hypersonic glide vehicle (HGV). This would be similar to how the DF-17 resembles a DF-16 with an attached HGV. US intelligence assessed in February 2023 that China conducted a developmental flight test of a “multirole HGV” for the DF-27, which flew for around 12 minutes and traveled approximately 2,100 kilometers (R. Chan 2023).

The Pentagon’s 2024 report noted that “China probably is developing advanced nuclear delivery systems such as a strategic HGV and a fractional orbital bombardment (FOB) system” (US Department of Defense 2024, 65). As of January 2025, China had tested each of these systems at least once. In July 2021, China conducted a test of a new FOB system equipped with a hypersonic glide vehicle, an event described as an unprecedented achievement for a nuclear-armed country (Sevastopulo 2021). According to the Pentagon, the system came close to striking its target after flying around the world, and “demonstrated the greatest distance flown (~40,000 kilometers) and longest flight time (~100+ minutes) of any [Chinese] land-attack weapons system to date” (US Department of Defense 2022b, 65). An operational FOB/HGV system would pose challenges for missile tracking and missile defense systems, as it could theoretically orbit around the Earth and release its maneuverable payload unexpectedly with little detection time, although the US missile defense system is not intended to defend against Chinese missiles.

Medium- and intermediate-range ballistic missiles

The most significant development in China’s medium- and intermediate-range ballistic missile force is the production and fielding of the dual-capable DF-26. Since 2018, the number of reported DF-26 launchers has increased from 18 to 250, with 500 missiles in 2024, according to Pentagon estimates (US Department of Defense 2024, 66). We estimate that approximately 250 DF-26 launchers are now fielded in seven brigades, with an eighth brigade under construction.

The DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) is dual-capable and launched from a six-axle road-mobile launcher. With its approximate 4,000-kilometer range, the DF-26 can target important US bases in Guam and Northeast Asia, as well as large parts of Russia and all of India.

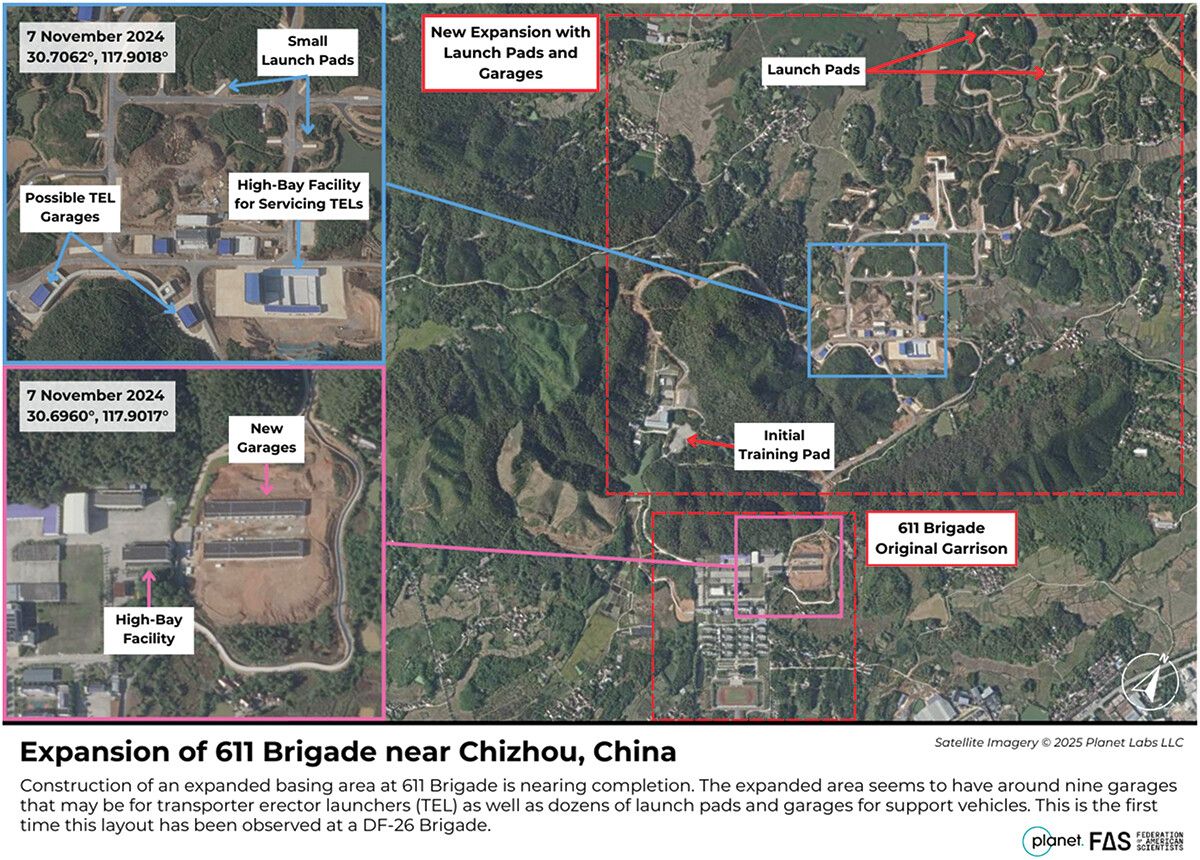

Although the total number of launchers has not increased since 2022, the base structure is undergoing significant developments. One of the most interesting is the expansion of the 611 Brigade (30.6903º N, 117.9011º E) near the town of Rongcheng, east of Chizhou in the Anhui Province. Chinese President Xi Jinping visited the base in October 2024 and was briefed on “the brigade’s newly introduced weaponry and equipment and examined its training in operating the arms” (Chinese State Council 2024). The new weapon referred to was the DF-26, which has been integrated with the base since 2021. A massive expansion—one that began in 2023 and is now almost complete—shows a completely new structure for a DF-26 base or any known PLARF base (see Figure 4).

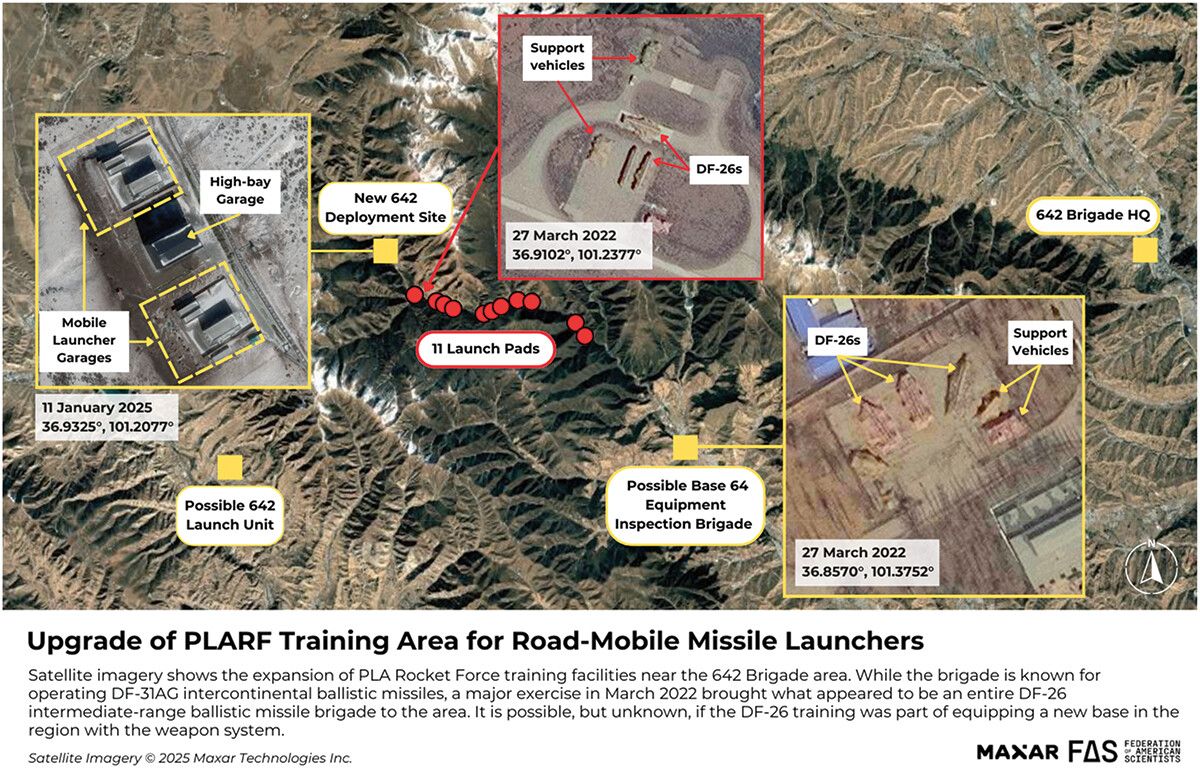

Significant developments for hosting the DF-26 are also underway at other bases. 642 Brigade at Datong in the Qinghai province is equipped with the DF-31AG ICBM but in March 2022, a large number of DF-26s (probably a whole brigade) conducted a large exercise west of Datong on a string of launch pads recently constructed along a road in the valley west of Base 64’s Equipment Inspection Brigade garrison outside Changwu town (36.852º N, 101.376º E) (see Figure 5). Commercial satellite imagery shows an estimated 24 DF-26 launchers participating in the exercise along the road and on the base itself. It is possible, but unconfirmed, that the DF-26s were visiting Base 64’s training center in Xining as part of their preparation for eventually integrating with the 647 Brigade garrison that is under construction 150 miles (240 kilometers) north in Zhangye. That garrison appears to be intended for 24 launchers.

As a dual-capable system, it seems unlikely that all DF-26s are assigned a nuclear mission. The DF-26 exists in three versions, of which one is thought to be an anti-ship version that is not nuclear-capable. Most DF-26s of the other two versions probably serve conventional missions, given that nuclear warheads have been produced for use by only some of the launchers. We estimate that perhaps a total of 100 warheads are assigned to the DF-26 force. One brigade, the 646 Brigade at Korla, is reportedly tasked with both nuclear and conventional strike missions, the first time this type of dual mission had been confirmed within a single brigade (Xiu 2022, 129, 131). To enable this dual mission, the DF-26 is reportedly capable of rapidly swapping out warheads, potentially even after the missile has been loaded onto its launch vehicle (Pollack and LaFoy 2020; US Department of Defense 2023, 67).

The dual-capable role of the DF-26, and the ability to change the launcher’s warhead in the field, raises some thorny issues about command and control and the potential for misunderstandings in a crisis. Preparations to launch—or the actual launch of—a DF-26 with a conventional warhead against a US base in the region could potentially be misinterpreted as the launch of a nuclear weapon and trigger nuclear retaliation—or even preemption. China is one of several countries (including India, Pakistan, and North Korea) that mix nuclear and conventional capabilities on medium- and intermediate-range ballistic missiles.

Citing Chinese defense industry publications, official media commentary, and military writings, the US Department of Defense assessed in 2024 that the DF-26 could eventually be used to “field a lower-yield warhead in the near term” (US Department of Defense 2024, 110). In addition, US STRATCOM Commander testified in March 2023 that China was making an “investment in lower-yield, precision systems with theater ranges” (Cotton 2023, 6). It is unclear what “lower-yield” warhead means; it is not necessarily the same as an explicitly “low-yield warhead.”

Separately, previous claims that the medium-range hypersonic glide vehicle-equipped DF-17 may be dual-capable have not been substantiated. The Pentagon’s 2022 China report had noted that “[w]hile the DF-17 is primarily a conventional platform, it may be equipped with nuclear warheads” (US Department of Defense 2022b, 65). However, this language was not included in the 2023 and 2024 reports, which only described the DF-17 as a conventional weapon (US Department of Defense 2023; 2024). Consequently, we do include the DF-17 in our estimate of Chinese nuclear forces.

The former mainstay of China’s regional nuclear missile capability, the DF-21A (CSS-5 Mod 2/6) medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM), has not been listed as operational in the last two Pentagon reports of Chinese military developments and may have been replaced by the DF-26 in the nuclear mission.

Submarines and sea-based ballistic missiles

China currently fields a submarine force of six second-generation Jin-class (Type 094) nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs), which are based at the Yalong naval base near Longposan on Hainan Island. The two newest SSBNs are believed to be improved variants of the original Type 094 design. Some Chinese journals refer to it as the Type 094A but this has not been confirmed by either the Pentagon or the Chinese government. These SSBNs include a more prominent hump, which initially triggered some speculation as to whether they could carry up to 16 submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), instead of the usual 12 (Suciu 2020; Sutton 2016). However, satellite images subsequently confirmed that the new subs are equipped with 12 launch tubes each (Kristensen and Korda 2020). The upgrades were later assessed to be related to sound silencing (Carlson and Wang 2023, 18).

Per the Pentagon’s most recent China Military Power Report, China has equipped its Jin-class SSBNs to carry either the 7,200-kilometer range JL-2 (CSS-N-14) SLBM or the longer-range JL-3 (CSS-N-20) SLBMs, and China has likely begun replacing the JL-2s with JL-3s on a rotational basis as each submarine returns to port for routine maintenance and overhaul (US Department of Defense 2023, 55). The range of the JL-2 is sufficient to target Alaska, Guam, Hawaii, Russia, and India from waters near China, but not the continental United States—unless the submarine sails deep into the Pacific Ocean to launch its missiles. With the JL-3’s longer range of roughly 10,000 kilometers, a submarine will be able to target the northwestern parts of the continental United States from northern Chinese waters, but not from the South China Sea. And it would still not be able to target Washington, DC without sailing past northeast Japan (National Air and Space Intelligence Center 2020, 33). Unlike the JL-2, the JL-3 allegedly can deliver “multiple” warheads per missile (National Air and Space Intelligence Center 2020, 33). It is unknown if the JL-3 is indeed equipped with multiple warheads; US intelligence has not explicitly stated that it is. The People’s Liberation Army Navy reportedly conducted its first test of the JL-3 in November 2018 (Gertz 2018) and appears to have conducted at least two—possibly three—additional tests since then (M. Chan 2020; Guo and Liu 2019).

Although the Jin-class is more advanced than China’s first experimental SSBN—the single and now inoperable Xia (Type 092)—it is a noisy design compared with current US and Russian missile submarines. It is estimated that the initial Type 094s was two orders of magnitude louder than the stealthiest Russian or American SSBNs (Coates 2016). However, the enhanced Type 094A SSBN is probably less noisy (Lin and Singer 2017). This may explain why China has decided to continue construction of additional Type 094A SSBNs, rather than transitioning entirely to the next-generation Type 096. Another reason may be due to production delays: The new Type 096 was scheduled to begin construction in the early 2020s, but after apparent delays, the Pentagon’s 2024 CMPR states that China will likely begin construction of the Type 096 “soon” (US Department of Defense 2024, 53).

In 2022, China completed a new construction hall at Huludao shipyard, where the People’s Liberation Army Navy’s submarines are built, which could be for the production of the Type 096 SSBN (Sutton 2020). Satellite images show wider hull sections at Huludao, which would make sense for the new SSBN that is expected to be larger and heavier than the Type 094 (Sutton 2021). However, we could not confirm whether the new facilities at Huludao correspond to the larger Type 096 SSBN or a new unknown attack submarine (see Figure 6).

As with all new designs, the Type 096 is expected to be quieter than its predecessor. Some experts even believe it could be as quiet as Russia’s new Borei-class SSBNs (Carlson and Wang 2023, 30). Although that would be a significant technological leap for China, The Financial Times reported in September 2024 that, according to US naval researchers, Russia was providing technological assistance to China to achieve a quieter propulsion system for its Type 096 submarines (Foy et al. 2024). Some anonymous defense sources have speculated the Type 096 will carry 24 missiles (M. Chan 2020), but no public official sources have confirmed this. Current and projected missile inventories seem to indicate that the new SSBN will more likely carry 12 to 16 missiles. The Pentagon’s 2024 report stated that the Type 096 SSBNs “will reportedly be armed with a follow-on longer range SLBM,” and that these SLBMs can be MIRVed (US Department of Defense 2024, 53, 88).

Given that China’s SSBNs are assumed to have a service life of approximately 30 to 40 years, the US Department of Defense expects that the Type 094 and Type 096 boats will operate concurrently (US Department of Defense 2024, 56). If confirmed, this could potentially result in a future fleet of eight to 10 SSBNs. All of China’s six SSBNs—and several attack submarines—are based at the Yalong naval base on Hainan Island where China appears to have completed construction of two additional piers to accommodate more submarines.

The Pentagon’s 2022 report indicated that China had begun “near-continuous at-sea deterrence patrols with its six JIN class SSBNs” in 2021 (US Department of Defense 2022b, 96), and the 2024 report asserted that China “probably continued to conduct” these patrols (US Department of Defense 2024, 104). The term “near-continuous” implies that the SSBN fleet is not on patrol all the time but that at least one boat is deployed intermittently. The term “deterrence patrol” could imply that the submarine at sea has nuclear weapons onboard, although US officials have not explicitly stated so. Giving custody of nuclear warheads to deployed submarines during peacetime would constitute a significant departure from Chinese declaratory policy and a significant change for China’s Central Military Commission, which has historically been reluctant to hand out nuclear warheads to the armed services.

To fully develop a survivable sea-based nuclear deterrent posture, China is presumably improving its command-and-control system to ensure reliable communication with the SSBNs when needed and prevent the crew from launching nuclear weapons without authorization. Moreover, the SSBN fleet will have to operate safely in patrol areas from where its missiles can reach intended targets. Western military officials have privately stated that the United States, Japan, Australia, and the United Kingdom “are already attempting to track the movements of China’s missile submarines as if they are fully armed and on deterrence patrols” (Torode and Lague 2019). Whenever they are in the South China Sea, China’s SSBNs typically appear to be accompanied by a protection detail, including surface warships and aircraft (and possibly attack submarines) capable of tracking adversarial submarines (Torode and Lague 2019).

Given the noise level of the SSBNs, it seems likely that China during conflict would keep the submarines inside a protected “bastion” in the South China Sea or the Bohai Sea (US Department of Defense 2024, 104). Even with the JL-3 SLBM, the SSBNs would not be able to target the continental United States from the South China Sea. To target the northwestern parts of the continental United States, they would have to sail far north, likely to the Bohai Sea.

Bombers

China developed several types of nuclear bombs and used aircraft to deliver at least 12 of the nuclear weapons that it detonated in its nuclear testing program between 1965 and 1979. Later, however, the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) nuclear mission became dormant as the rocket force improved and older intermediate-range bombers were unlikely to be useful or effective in the event of a nuclear conflict. While we previously estimated that China maintained a small inventory of gravity bombs for potential contingency use by aircraft, we assess that this mission no longer exists and that China no longer retains gravity bombs in its nuclear arsenal.

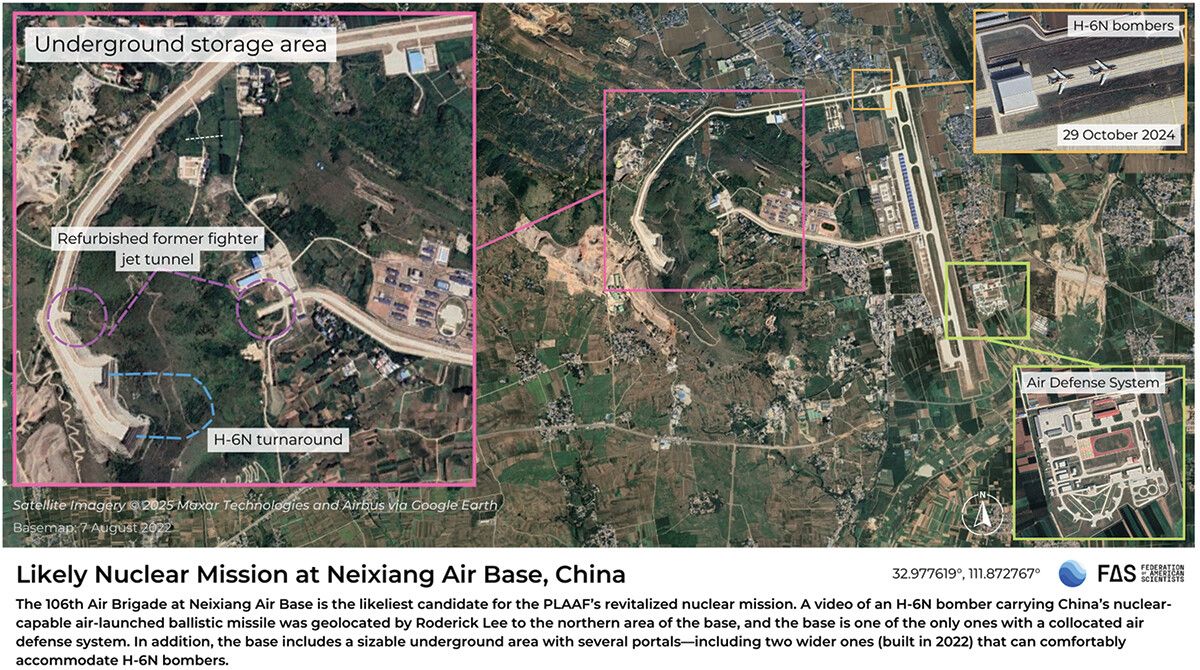

The PLAAF’s nuclear mission remained dormant until approximately 2017–2018, when, coinciding with a renewed emphasis on nuclear aircraft modernization, the US Department of Defense reported in 2018 that the PLAAF “has been newly re-assigned a nuclear mission” (US Department of Defense 2018a, 75, 34). This new mission appears to be currently centered around China’s current H-6 “Badger” bomber. China has hundreds of these aircraft in more than eight distinct variants; however, only one of these variants was assessed to be nuclear-capable: the H-6N.

The H-6N is distinct from other variants of the H-6 in that it incorporates a nose-mounted in-flight refueling probe, allowing it to travel much further (Rupprecht 2019). Notably, however, the H-6N airframe modification includes the removal of the bomb bay, supporting the conclusion that China’s legacy gravity bomb mission has indeed ended. In November 2024, China and Russia conducted joint air drills that, for the first time, included the participation of the H-6N (Global Times 2024).

The modified fuselage of the H-6N can accommodate air-launched ballistic missiles (ALBMs). China is developing at least two types of ALBMs, both of which appear to be variants of land- or sea-based ballistic missiles. The 2PZD–21 (also sometimes called the KD-21) ALBM appears to be a wing-mounted air-launched version of the YJ-21 sea-launched anti-ship ballistic missile, indicating it likely has a conventional strike role (Panda 2019; Rupprecht 2024).

China’s other ALBM, referred to by the US Department of Defense as “nuclear-capable,” was previously designated by the United States as CH-AS-X-13. (It is possible, but unconfirmed, that the X has since been removed from the designation, given the system is now deployed.) The missile was spotted in video footage from 2020 and 2022, in which the aircraft appeared to carry a hypersonic glide vehicle very similar to the one carried by the DF-17 medium-range ballistic missile (OedoSoldier 2020; Rupprecht 2022). However, the Pentagon’s 2024 China Military Power report specifically noted that the ALBM “appears to be armed with a maneuvering reentry vehicle,” suggesting that the two payloads are distinct (US Department of Defense 2024, 105).

Following at least five developmental and user tests, the Defense Intelligence Agency assessed in August 2024 that the CH-AS-X-13 has now been deployed (Defense Intelligence Agency 2024, vi). The Pentagon assessed that the deployment of the nuclear ALBM provides China “with a viable nuclear ‘triad’ of delivery systems dispersed across land, sea, and air forces” (US Department of Defense 2019, 67). Yet the Chinese “triad” is much less complete or capable than the U.S. and Russian triads.

Currently, only one PLAAF unit is publicly known to have a nuclear mission: the 106th Brigade at Neixiang Air Base in the southwestern part of Henan province. Over the past five years, the base has been modified extensively, including the addition of large tunnel entrances into a nearby mountain wide enough to comfortably accommodate the H-6N bomber (see Figure 7). Civilian video footage from October 2020 appears to show an H-6N bomber flying with the possible new ALBM just outside of Neixiang Air Base, one of China’s only airfields with an adjacent air defense site (Lee 2020a, 2020b; Rupprecht and Dominguez 2020). The numbers of H-6N bombers and their assigned nuclear weapons are unknown, but we cautiously estimate that 20 aircraft are assigned up to 20 missiles. It is unknown how many nuclear bomber brigades China plans to establish, but satellite imagery shows significant construction as well as some H-6 bomber operations at Lu’an Air Base in the eastern part of the Anhui province.

To eventually replace the H-6, China is developing a stealth bomber with a longer range and improved capabilities. The Pentagon estimates that the new bomber, known as H-20, will have both nuclear and conventional capability and a range of more than 10,000 kilometers. If equipped with an aerial refueling capability, the Pentagon assesses that the bomber could potentially have an intercontinental range (US Department of Defense (2023, 92). In early January 2025, a video surfaced on the Chinese social media platform Weibo allegedly showing the maiden flight of the H-20 stealth bomber; however, the video has not yet been authenticated and may be AI-generated, nor has the flight been confirmed by official sources (前HR本人 2025; Tirpak 2025).

Cruise missiles

From time to time, various US military publications have asserted somewhat vaguely that one or more of China’s cruise missiles might have nuclear capability. For example, a nuclear modernization fact sheet published by the Pentagon in connection with the release of the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review claimed, without identifying them, that China had both air-launched and sea-launched nuclear cruise missiles (US Department of Defense 2018b). The Pentagon has not substantiated this claim since. The 2023 Japanese Defense Paper, however, stated that the H-6 bombers “are believed to be capable of carrying long-range attack cruise missiles with nuclear capability” (Japanese Ministry of Defense 2023, 67).

It is still unclear what this missile could be—if it exists at all. Therefore, we continue to assess that, although China might have developed warhead designs for potential use in cruise missiles, it currently has no nuclear cruise missiles in its active stockpile. It is possible, but unconfirmed, that the future H-20 could be equipped with a nuclear cruise missile.

The authors wish to thank Allie Maloney, the Herbert Scoville Jr. Peace Fellow at the Federation of American Scientists, for her help with generating critical research and graphics for this production.

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Jubitz Family Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and individual donors.

Notes

[1] Nuclear weapons are stored in central facilities under the control of the Central Military Commission. Should China come under nuclear threat, the weapons would be released to the Second Artillery Corps to enable missile brigades to go on alert and prepare to retaliate. For a description of the Chinese alerting concept, see Kristensen (2009). For more on warhead storage in China, see Stokes (2010). For an overview of the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force structure and organization, see Stokes (2018) and Xiu (2022). For an insightful overview of Chinese thinking about nuclear weapons and policies, see Santoro and Gromoll (2020).

[2] The “continental United States” as used here includes only the lower, contiguous 48 states. US states and territories outside of the continental United States include Alaska, Hawaii, Guam, American Samoa, Puerto Rico, the US Virgin Islands, and many tiny Pacific islands.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: China, Nuclear Notebook, ballistic missiles, nuclear arsenals, nuclear risk, nuclear weapons

Topics: Nuclear Notebook, Nuclear Weapons