The many lessons to be drawn from the search for Iraqi WMD

By Terence Taylor | July 21, 2021

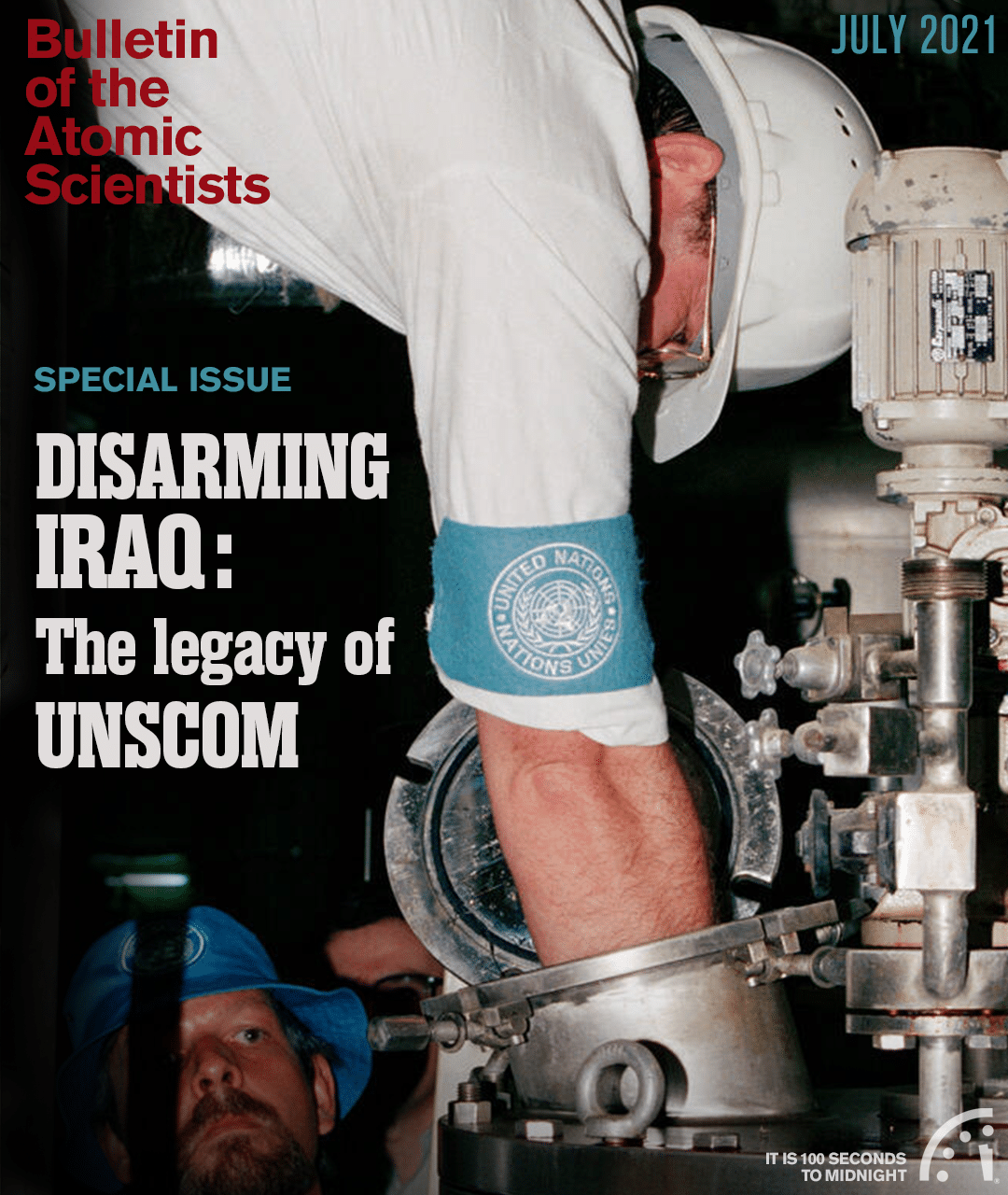

A member of the UN Special Commission inspection team uses a chemical air monitor in April, 1992, to detect leakage from a CS-filled 120mm mortar shell at Fallujah Chemical Proving Ground, as part of the effort to verify Iraq's compliance with the order to destroy its chemical munitions and weapons of mass destruction. File photo UN7772056 courtesy of UNSCOM

The many lessons to be drawn from the search for Iraqi WMD

By Terence Taylor | July 21, 2021

Loading...

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Get alerts about this thread

0 Comments

Oldest