Introduction: Nuclear testing in the 21st century—legacies, tensions, and risks

By François Diaz-Maurin | March 7, 2024

Introduction: Nuclear testing in the 21st century—legacies, tensions, and risks

By François Diaz-Maurin | March 7, 2024

Despite an international treaty banning all nuclear detonations, the issue of nuclear weapons testing is taking center stage once again. Last November, Russia officially withdrew its ratification of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. Earlier in 2023, Russian President Vladimir Putin stated that Moscow will not resume nuclear testing “unless the United States does so”—a possibility experts view as highly unlikely under the current US administration.

But despite officials—in Russia and elsewhere—saying that they will not resume nuclear testing, some evidence could suggest otherwise.

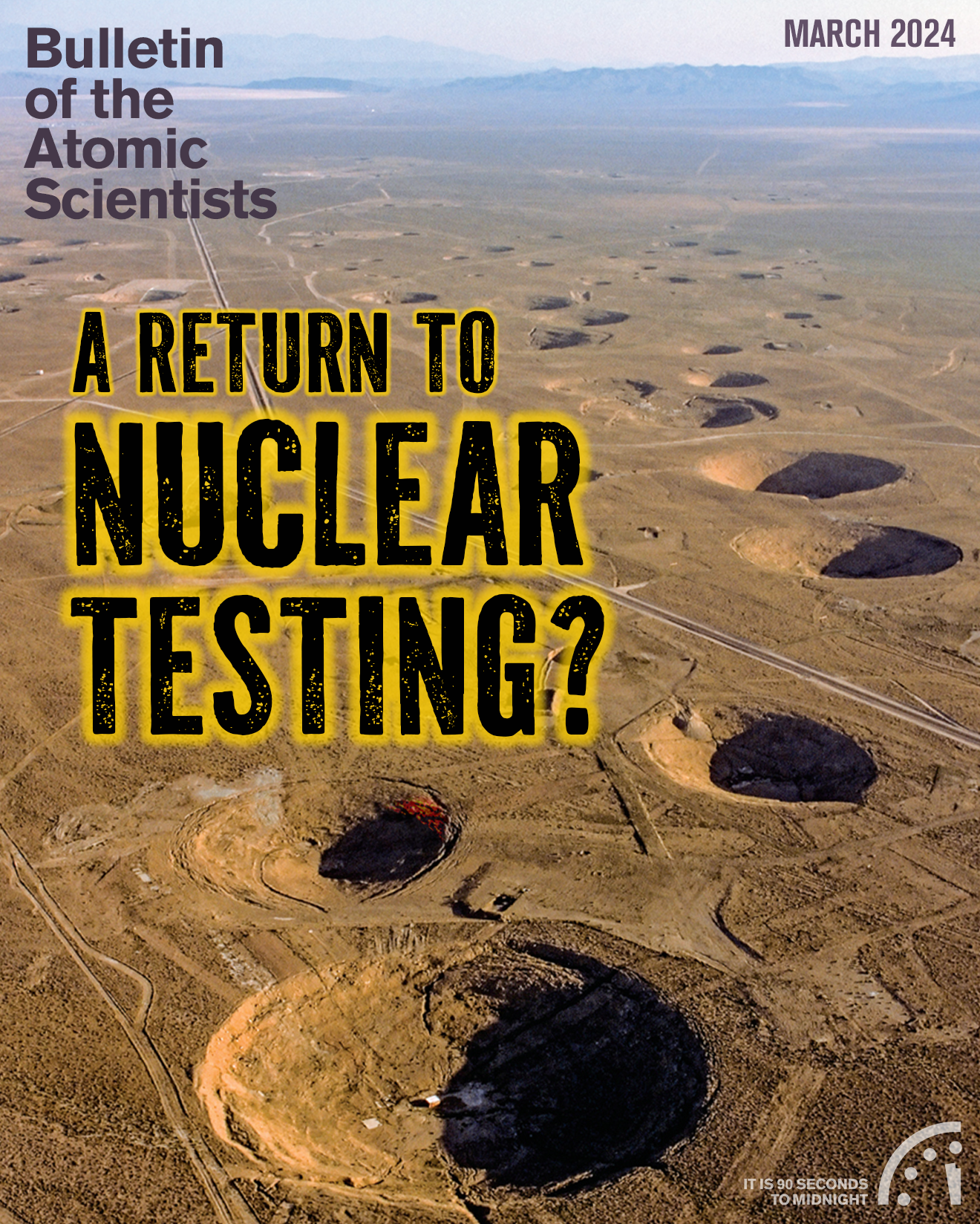

Satellite imagery has shown increased construction activities happening since 2021 in recent years at nuclear testing sites in the United States, Russia, and China—the world’s three largest nuclear powers.

Experts believe that Russia and China are currently expanding underground tunnels at their nuclear test sites of Novaya Zemlya and Lop Nur, respectively. In the United States, the National Security Administration is also expanding the Nevada Test Site, officially to improve the diagnostic capabilities for the management and performance of the US nuclear stockpile, without the need to conduct any more underground nuclear explosive tests. But, at the same time, the United States maintains a policy of readiness, by which the country is prepared to conduct a nuclear test within six months should one of its adversaries conduct one.

In this game of who-moves-first, other nuclear-armed countries are watching closely.

North Korea is ready to conduct another underground nuclear test—its seventh—and is only waiting a political decision by Leader Kim Jong-un to do so, which may come at any time. North Korea is the only country to have tested nuclear weapons in the 21st century. Also watching are India and Pakistan—countries whose latest tests were conducted in 1998 and who haven’t signed the test ban treaty. They may seek any opportunity to test another nuclear device.

To help make sense of how recent developments are putting to test the resolve of nuclear powers to continue with observing their testing moratoria, policy experts and scientists provide here a comprehensive set of articles about the current challenges of nuclear weapons testing—from the enduring legacy of past nuclear tests to the new tensions over suspected testing activities.

In “The logic for US ratification of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty,” Steven Pifer, the former US Ambassador to Ukraine, explains why it would be in the interests of the United States to ratify the nuclear test ban treaty.

Nuclear expert Pavel Podvig argues in his piece, “Preserving the nuclear test ban after Russia revoked its CTBT ratification,” that transparency in the US nuclear experiments will be critical to preserving the moratorium on nuclear explosions and could encourage Russia and China to be more transparent about their activities too.

In her piece, “To do or not to do: Pyongyang’s seventh nuclear test calculations,” nuclear policy expert Rachel Minyoung Lee asks the Shakespearean question of why North Korea may—or may not—conduct its next underground nuclear test.

In a more technical article, Earth scientists Sulgiye Park and Rodney C. Ewing review the long-term environmental impacts of past underground nuclear tests. In a similarly technical piece, physicists Julien de Troullioud de Lanversin and Christopher Fichtlscherer explain the fuzzy line between nuclear tests and nuclear experiments—and how arms control tools can help reduce tensions around the various interpretations of what “zero yield” means.

In his piece, Walter Pincus, former Washington Post reporter and author of the book Blown To Hell about US nuclear testing, reminds Bulletin readers what a single nuclear test explosion in the atmosphere can do—something new generations cannot grasp easily, given that the last known atmospheric test was conducted in October 1980 (by China).

Finally, in their latest column of the Nuclear Notebook, “Russian nuclear weapons, 2024,” Hans M. Kristensen, Matt Korda, Eliana Johns, and Mackenzie Knight of the Federation of American Scientists’ Nuclear Information Project discuss recent activities at the Novaya Zemlya test site and Russia’s withdrawal of its ratification from the nuclear test ban treaty.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.