Introduction: Praying for the ice (and snow, and water) as the climate changes

By Dan Drollette Jr | July 15, 2024

Introduction: Praying for the ice (and snow, and water) as the climate changes

By Dan Drollette Jr | July 15, 2024

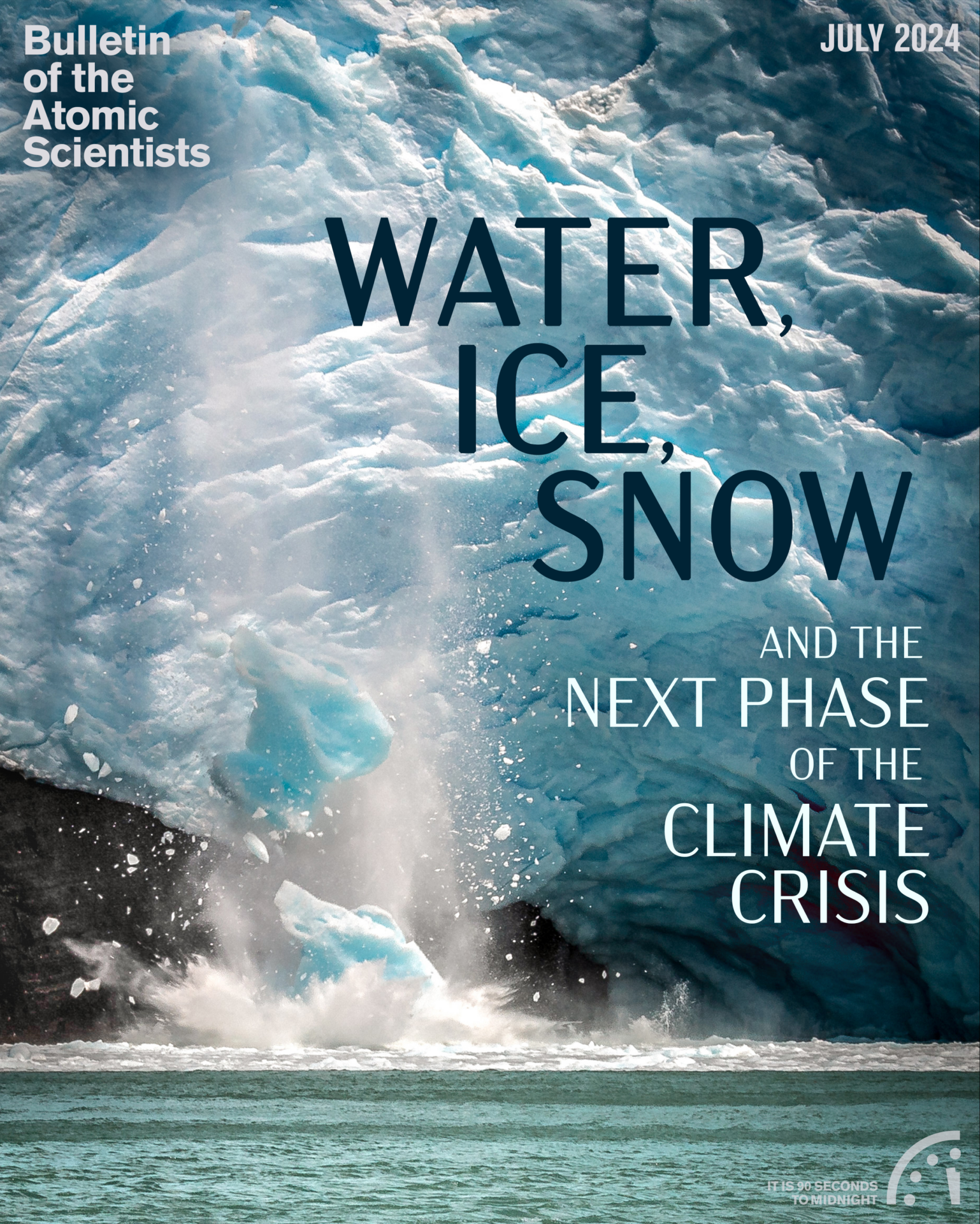

In 1678, the inhabitants of the Swiss village of Fiesch became fed up with the ever-growing glacier next door—the Aletsch, largest in the Alps—which was swallowing their homes and fields. So they conducted a five-hour religious procession, in hopes of stopping the ice’s relentless advance with prayers, chants, and holy water. Their efforts appeared to have worked: The glacier stopped advancing. A religious procession for the glacier still takes place to this day every July 31 and ends at the Ernerwald Chapel, on the outskirts of town.

What they pray for, however, has changed.

Now, the ice and snow is in danger of nearly disappearing. The loss of what is colloquially known in Switzerland as “the white gold” has been endangering not only the village’s supply of water but their tourist income—as well as making the neighboring mountains more unstable, due to the melting of the underlying permafrost that binds their slopes together. “Without the glacier, the springs run dry, and the brooks evaporate. Men and women face great danger. Alps and pastures vanish, and towns die out,” said the Reverend Pascal Venetz in a sermon to the village.

Consequently, over a dozen years ago, on behalf of Fiesch, the nearby bishop petitioned the Vatican to approve a change to the processional liturgy, enabling villagers to ask the heavens to stop the region’s glaciers from shrinking any further. “We should pray that our glacier does not melt any further, but instead grows, and that the most important thing in life, water, remains well preserved,” Venetz told parishioners.[1]

It all may sound quaint and fairy tale-like, but the shrinking of the Alp’s glaciers is very real and very serious, affecting an icon of the country. (Try to imagine Yellowstone without geysers.) And the experience of this village with shrinking glaciers is not unique: Drive around Switzerland and you’ll find commemorative signboards marking the long-ago endpoints of many of the country’s glaciers—often in lush green meadows far removed from the faintest hint of ice or snow.

To get a sense of what is happening—and what could possibly be done about it—glaciologist Matthias Huss of the Swiss glacier monitoring network writes in this issue of the Bulletin about the past and future changes of glaciers in Europe and around the world because of climate change, and the corresponding downstream effects of those changes. While Huss despairs of the loss of many of the Alps’ smaller glaciers—some of which, after decades of study, he calls “old friend[s]”—he does not give up hope. Huss says: “It is not yet too late to act and to prevent the demise of the biggest ice masses worldwide.”

And some of the world’s biggest ice masses are indeed at stake. In his article “How we know Antarctica is rapidly losing more ice,” climate scientist/polar explorer Martin Siegert explains how greenhouse gasses are causing changes to the Antarctic ice sheet that haven’t been seen for geological eons—changes that researchers are documenting via satellite measurements, lidar, and radio-echo sounding surveys that penetrate through the ice to the bedrock underneath. (Seismic measurements also revealed just how much ice is involved: The ice cap is nearly two-and-a-half miles thick in parts of Antarctica. If all of it melted, the oceans would rise 197 feet.)

It turns out that Antarctica is affected by more than just rising temperatures in the atmosphere. There is also heat exchange occurring in the seas, along with the continent’s “marine ice cliff instability.” Scientists recently found that when a colossal, kilometer-long chunk of ice crashes from a cliff into the ocean, it causes massive underwater tsunamis that can extend for miles, mixing the levels of warm and cold water along the ice edge, which then leads to more melting. This constant churning and mixing has only now been appreciated as a significant contributor to ice melt, as ocean scientist Michael Meredith writes in this issue in “When glaciers calve.”

To slow and eventually stop the melting of the world’s glaciers, the world needs to stop burning fossil fuels and warming the oceans and the skies. But as Pulitzer Prize-winning author (and former Bulletin Science and Security board member) Elizabeth Kolbert notes, policy makers and the press keep getting fixated on the latest gee-whiz technological quick-and-dirty so-called “solution” to climate change-related problems, no matter how bizarre it may be. In her interview, Kolbert tells of how venture capital seems enamored of long-shot engineering efforts, partly because they fit in with what she calls “tech-bro” culture.

One of the ideas includes putting a 60-mile long underwater plastic curtain along the Antarctic coast to prevent warm ocean water from getting to it—an expensive proposition that geoscientist Rob DeConto thinks is an absurd distraction from reducing the greenhouse gas emissions that are causing the global warming that threatens water resources, frozen or liquid, worldwide.

In his interview for this issue, DeConto discusses the possibility that the latest computer-modeled projections severely underestimate the amount of sea-level rise that could come as the melting of the ice caps that cover Greenland and Antarctica continues. There’s a 17-percent chance that even the most dire estimate—a meter of sea-rise by the end of this century—could be far too low.

While 17 percent doesn’t sound too bad at first, this kind of “low-likelihood, high-impact” projection should not be ignored. As DeConto puts it: “[I]f there was a 17-percent chance that the airplane you were getting on wasn’t going to make it to its destination, you’d be thinking twice about getting on that plane.”

And maybe praying.

Endnotes

[1] For more, see “Can the pope save Europe’s largest glacier?” Swissinfo.ch https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/culture/can-the-pope-save-europe-s-largest-glacier/32914

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Alps, Antarctica, ICE, climate crisis, glaciers, peak water, sea level rise, snow, water

Topics: Climate Change