Global and regional confrontation in South and Southeast Asia

By Achin Vanaik | March 10, 2022

Global and regional confrontation in South and Southeast Asia

By Achin Vanaik | March 10, 2022

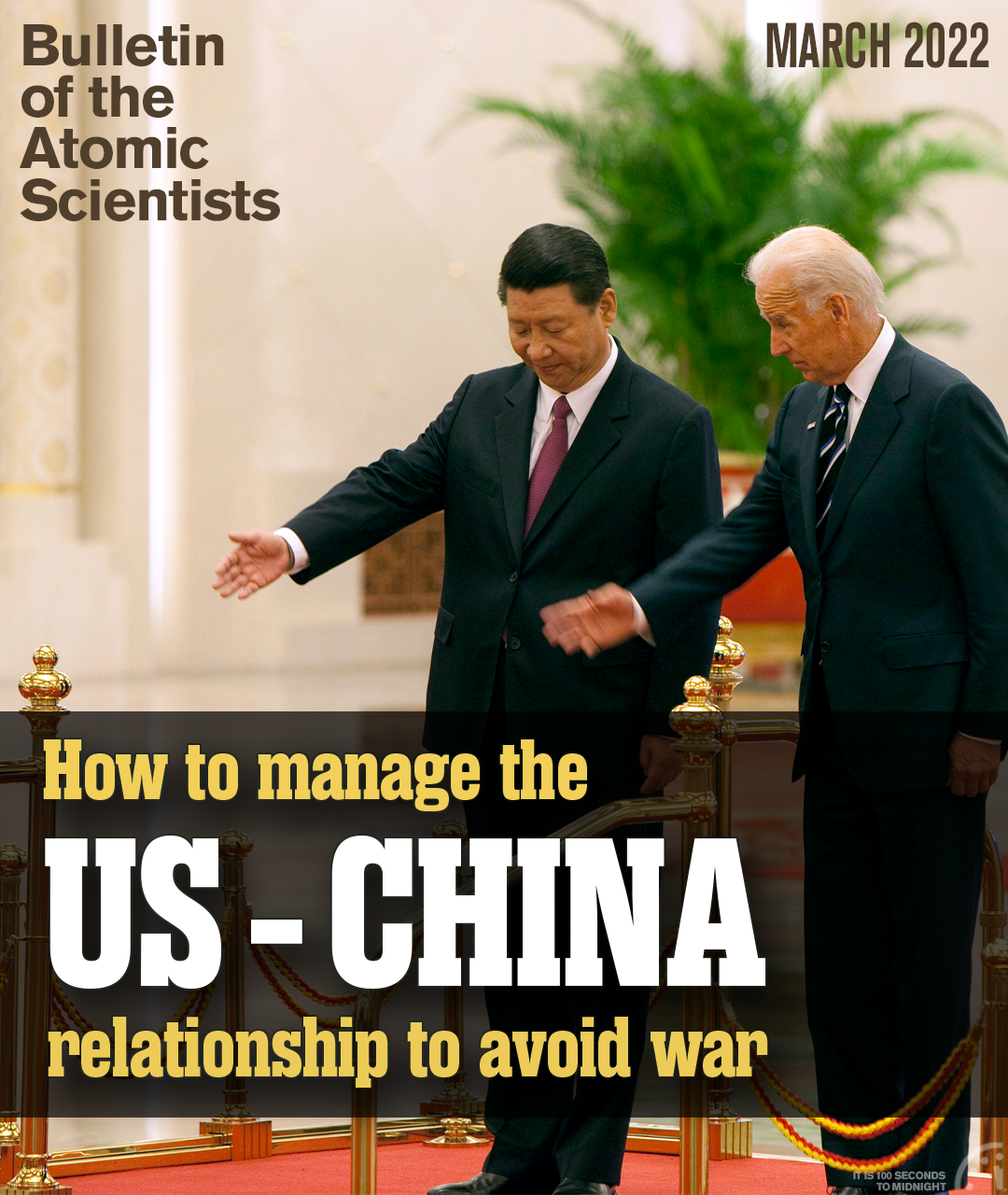

In assessing the global geopolitical order within which the situation in South and Southeast Asia is playing out, let us start with the obvious: The United States remains the single most powerful country and will remain so for a considerable time to come. Russia is a rough equal only in respect to its nuclear arsenal and delivery capabilities. China will soon become in terms of total economic output the world leader, but its per capita income level will not approximate even those of the smaller West European countries any time soon.

The military hardware and software balance is even more in favor of the United States. On the hardware side, the United States has over 750 military-related bases around the world, an unmatchable level of military expenditure year after year (roughly $750 billion), and a worldwide network of alliances. With regard to cutting-edge technologies, China is challenging for primacy in a few areas, but cannot match the wide spectrum of possible technological advances that the United States can generate, given its lead in the quantity and quality of its research universities. Unlike the United States, China faces serious domestic ethnic pressures in Xinjiang and Tibet, and is also surrounded by a host of countries which—although increasingly tied into its economy—welcome the US’s military-political presence in East and Southeast Asia as a desirable countervailing power. Clashing territorial claims in the South China Sea have become yet another reason that many countries other than China want the US presence there to continue.

Global influence requires not just the passive consent that comes from fear or the bought consent that comes from inter-state bargaining, but the active consent that comes from popular appreciation and the desire to emulate. Here, too, there is no comparison between China and the United States. Many more of the world’s young and talented seek to migrate to the United States rather than China. English is the international language. The democratic structures of the United States and its allies in the West, despite increasing erosion of their substantive content, compare favorably with anything on offer from China. Meanwhile, the sources of popular culture in dance, music, cinema, TV, and spectator sport that stimulate emulation and adaptation come mainly from the United States and Europe.

What is the point of recounting these distinct advantages of the United States?

First, it is to highlight that this reality has helped to promote a very dangerous illusion—that the United States can actually be the world protector or savior, rather than what it has actually been, the principal source of global disorder. It has fought more wars, overt and covert, than any other country since World War II and since 1945 killed more civilians outside its home territory—in the several millions—than the external actions of all the rest of the world’s countries put together. [1]

What is more, this search for global dominance seems likely to continue. On this, American hardliners and the liberal internationalist wing within the foreign policy establishment agree. Where the former talk of the United States as the “Empire of Liberty,” the latter talk of the America as the “hegemonic stabilizer” that is said to be the necessary but not sufficient condition for providing the “international public good” of stable peace and prosperity (Ferguson 2004). Tactical differences between hardliners and liberals on how best to pursue this common goal is important and does lead to different and shifting combinations of coercion, bargaining, and cooperation in the exercise of US foreign policy (Stokes 2018).

Second, pointing out US primacy in detail explains why, over the next two decades or more, China is not going to replace the United States as the world’s leading power. In fact, the foreign policy behavior of Russia and China has to a very great extent been reactive to what the United States does and thinks. (This must not be taken as exculpation for the undeniable brutalities and iniquities carried out by the governments of these two countries at home or abroad. Chinese military expansionism in the South China Sea is not simply reactive. Xi Jinping in his speech in October 2017 at the party’s 19th Congress made it clear that his country’s goal of “national rejuvenation” includes—as the military counterpart of its economic expansion via the Belt and Road Initiative and maritime networks to Africa, Eurasia and South America—the creation by mid-century of “world class forces” that will match those of the United States.)

Since Obama’s so-called “pivot to Asia” in 2012, the lines of confrontation rather than cooperation have become clearer. In US eyes, China has graduated from once being a strategic partner to the status of a competitor or rival to now being an opponent—and even in some circles an enemy that must be dealt with. There is a stronger force deployment closer to China and a war-fighting strategy called the Air Sea doctrine in which exercises for a possible conflict with China have been carried out. The creation of the Quad (comprising Japan, US, Australia and India) and the AUKUS (Australia, United Kingdom, and the United States) security agreement is clearly geared towards controlling the Indo-Pacific waters, adding the economic threat of blocking China’s sea routes to the wider security architecture for its containment.

Russia is wary of China’s growing strength but the possibility of an emerging Russia-US entente (the mirror reflection of the US-China entente during the Cold War) against China is very remote. This is because of US nuclear preparations, particularly its ballistic and theater missile defense systems, which are targeted at Russia as well as China; and concern over a NATO which, not content with having expanded eastwards to Russia’s “near abroad,” aims to include a more than willing Ukraine, the second most powerful country to emerge from the Soviet break-up. This American-led project is currently in abeyance, given the outcome of the recent summit meeting between Biden and Putin held at a time of rising Russia-Ukraine tensions. But it has by no means been shelved. The result is that Russia sees no option but to forge a closer, even strategic, relationship with China, and in November 2021 the two countries agreed that there be a five-year 2021-2025 plan for developing even closer military cooperation.

These then appear to be the main parameters of great power rivalry today and for the foreseeable future. So where do India and Pakistan fit in, and how have their respective relationships with the United States and China evolved as America pivots to Asia?

The unstable standoff between India and Pakistan

Since their formation as independent states in 1947, mutual hostility has reigned between India and Pakistan. The dispute over Kashmir has been a key and enduring reason for this to which other developments over time have added their own weight. Unlike the old US-Soviet Cold War face-off, the South Asian version has witnessed four direct wars between the two countries, the last in 1999—the first war between two nuclear powers. On some occasions thereafter, tensions could well have reached that level again.

In the Cold War era, Pakistan was a coveted ally of the United States in its anti-Communist/anti-Soviet crusade. In the 1970s, a number of changes took place. In 1971, Pakistan was dismembered, losing its more populous eastern section, which, with Indian military intervention, became the independent state of Bangladesh. Not long after, Pakistani strategists began talking of the need to have “strategic depth” in bordering Central Asia to cope with a possible future invasion by a militarily preponderant India (Hoodbhoy and Mian 2014). The US reaction to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 made Pakistan an even more important ally, giving real flesh to this pursuit of strategic depth. Earlier in the same decade, the US-Chinese entente directed against the Soviet Union (and North Vietnam) allowed Islamabad and Beijing to come closer, a shift that made sense in both capitals given that, in varying measures, India was a common point of negative reference (Ahmed 1999). It is widely believed that Pakistan, sometime after India’s own “peaceful nuclear explosion” in 1974, received a nuclear bomb design from China (Weiner 1998).

Apart from its rivalry with Pakistan, for India another constant since the 1962 Sino-Indian border war was Indian hostility to China. This has never been as deep-seated as its hostility to Pakistan. For China, the victor, this was a mere border dispute that need not have resulted in a war if only India had been prepared to renounce boundaries established by British imperialism and gone in for reasonable give-and-take exchanges along the over 4,000-kilometer (about 2,485 miles) boundary between the two countries. China, after all, got what it wanted.

For India, the loser, there is a more enduring bitterness and a sense of humiliation that has soured relations with its Asian neighbor, despite the historical absence of any conflict between the two civilizations across centuries. Despite India’s declared policy of non-alignment during the Cold War period, given the close US ties with China and Pakistan, India had a strategic tilt toward the Soviet Union.

It was the Soviet bloc collapse and the West’s Cold War victory that dramatically re-assembled the strategic ties of both South Asian countries with the United States. The 1991 Congress-led Indian government decisively opened the economy on the trade, investment, and finance fronts—a process of integration into the neoliberal capitalist global order that, with all its halts and hesitancies since then, has deepened. This has reinforced India’s foreign policy shift towards seeking closer relations with the United States as a way over time to outflank and seriously weaken the latter’s ties with Pakistan, while also offering itself—an obvious emerging power—as a major Asian friend and potential partner. During the period of 1991-98, Sino-Indian relations also improved with the signing of two agreements greatly easing border tensions. Before 9/11, the US reliance on Pakistan for support to its policies and actions in Afghanistan no doubt acted as a brake of sorts on the diplomatic-military relations between New Delhi and Washington, which did advance, but slowly.

The 1998 nuclear tests by India followed by those of Pakistan shocked the United States and its admittedly selective support for non-proliferation (Israel is always left off the hook). That this dual acquisition of nuclear weapons made South Asia the world’s most dangerous nuclear flashpoint was confirmed in the 1999 Kargil war, when both sides prepared their nuclear arsenals for possible use (Joeck 2010). The US stepped in on the Indian side getting Pakistan to withdraw its troops. Since then the US has reconciled to the Indian acquisition of nuclear weapons as relations between the two have steadily improved between 9/11 and the present. In the same period, there have been ups-and-downs in the US-Pakistan relationship, but the overall outcome seems to be a game-changing marked decline. Indeed, there have been four inter-related reasons for these changes in the US-Pakistan-India triangle: the 9/11 terror attacks; strategy shifts in the US-China relationship towards greater mutual enmity; the Afghanistan imbroglio; and the new alignments in the Middle East clearly expressed by the Abraham Accords (Bidwai and Vanaik 1999).

Pakistan and the United States: before and after 9/11

The geopolitical heart of Eurasia and North Africa consists mostly of Muslim-majority countries where resistance to American plans and actions has for one reason or the other been great. Pakistan, the second most populous Muslim country, bridges the Middle East and Central Asia. Comparatively speaking, in the Muslim world, Pakistan has long had the largest pool of skilled scientists and technicians, the most sophisticated and battle-hardened armed forces, the bomb, and a longstanding alliance with the United States.

Pakistan has also had close military ties with Saudi Arabia. It has been the vantage point for the expansion of American influence and power in Afghanistan and beyond it to the Central Asian republics. These are not assets that the US could easily dismiss. So even after the end of the Cold War and the developing camaraderie between the United States and India, Washington still saw each South Asian country serving non-substitutable geopolitical interests for its imperial ambitions—Pakistan for what it could offer westwards to the Middle East and northwards to Central Asia; India for what it could offer southwards in respect of allied control over the Indian ocean region and eastwards vis-à-vis China.

This did not prove to be a stable situation.

The broad trajectory of developments from the pro-communist Saur revolution of 1978 to Soviet invasion and occupation to the US invasion and final withdrawal from Afghanistan is by now well-known and needs no re-telling (Ellison 2017).

But how it affected the US-Pakistan relationship does bear explication.

Pakistan was the key US ally for transporting vital material support to radical Islamist groups that enabled them to defeat the Soviet Union and eventually overthrow its client regime. Amid inter-group rivalries, the Pakistan spawned the Taliban (in its original version), which succeeded in ascending to power in the mid-90s and expanding its control over much of the country—until the 9/11 attacks. The subsequent US military occupation of Afghanistan and installation of what some saw as puppet regimes repeated the drama that the Soviets had encountered. Various radical Islamist groups worked against and within the state apparatuses to expand their power, reach, and profit. The final victor turned out to be a more cautious and calculating Taliban, still having close relations with the Pakistan government but far more independent, having in the course of the struggle against US occupation and its domestic allies established a fairly solid mass base in the country.

In fact, what has come out of the US debacle in Afghanistan is the emergence of a likely new quartet—China, Russia, Iran, Pakistan—enjoying dominant external influence with the new Taliban government. Pakistan and Iran (along with Afghanistan) will be participants in China’s Belt and Road Initiative. All four members of this quartet see the United States as their main problem, a country out to destabilize each of them as much as possible.

In varying degrees, they all offer Afghanistan economic help and political-military protection, domestic and foreign—provided the Taliban government duly reciprocates. For Pakistan and Iran, this means preventing a major influx of refugees and opium into their countries from Afghanistan. China is expected to repress certain Islamist groups that are keen to support insurgent elements in Xinjiang. Russia sees Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan—which all border Afghanistan—as falling within its sphere of influence. That these are ruled by highly authoritarian governments is not an issue, but opposition to each of them is led by domestic Islamist groups. In Russia’s view, the Taliban should see to it that they do not receive support from sympathizers in Afghanistan.

The US withdrawal from Afghanistan and its retreat more generally from Central Asia (at least for some considerable time) does mean that Pakistan may no longer be seen as a useful US ally. In any case, Islamabad’s ties with Kabul and its own hosting of certain radical Islamist groups that align with its own foreign policy ambitions amid growing Islamophobia in the United States and the West has also been an alienating factor. Also, Pakistan’s relevance for US perspectives in the Middle East has also been further downgraded, now that Saudi Arabia has come closer to Israel and the two see Iran as their major opponent, a country with which Pakistan is pursuing closer relations. No surprise then to see that Indo-US relations are getting steadily stronger while Pakistan-China ties are also deepening—each dynamic reinforcing the other.

India’s shifting posture

Indo-US relations have moved forward steadily since 9/11, no matter who rules in New Delhi. The major breakthrough came in 2008, with the Indo-US nuclear deal. In return for India’s strategic realignment with the United States in its broader foreign policy perspectives, India was allowed join the Nuclear Suppliers Group, the non-proliferation rules of which were re-jiggered, courtesy of US-led efforts. But a series of other US-India agreements surrounded the nuclear deal, including the 10-year Defense Framework Agreement. The advent of the Modi government further deepened the military relationship; and in 2015 the defense agreement was renewed for another 10 years. Two agreements were signed in 2016 and 2018 and a third will follow. The first of these was LEMOA (Logistics Exchange and Memorandum of Agreement) enabling port calls, logistical support, joint exercises and training. Second was COMCASA (Communications Compatibility and Security Agreement) which allows much closer sharing of information and the transfer of advanced communication technology. BECA or Basic Exchange and Cooperation Agreement for Geospatial Cooperation will be next. In June 2020, to consolidate the Quad, Modi signed an Acquisitions and Cross-Servicing Agreement (ACSA) with Australia opening bases for each other’s army, navy, air-force. A similar deal is on the anvil for Japan with which country there are already joint military exercises of all three arms.

What of the India-Pakistan and India-China face-offs under Modi? A major reason, perhaps the major one, for deteriorating relations in both cases are Modi’s deliberate and calculated displays of belligerence. Though an anti-Muslim orientation is foundational to the ideology and practices of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), raising the anti-Pakistan banner domestically pays greater dividends popularity-wise.

A few months before the general elections in May 2019, a suicide bomb attack killed 40 paramilitary police at Pulwama in the state of Jammu and Kashmir. The bomber was a local Kashmiri youth, Ahmad Dar, trained by the Jaish-e-Mohammad group in Pakistan. (Both India and Pakistan claim Kashmir, but each controls only part of the province.)

Though the Pakistan government condemned the attack and denied all connection, Modi launched a major air assault on an alleged training camp in Pakistan territory. Air skirmishes also took place, with an Indian plane downed and its pilot captured. Shortly afterwards both sides agreed to reduce tensions and the pilot was released and returned. Incidentally, this assault did significantly help Modi secure a very large majority of parliamentary seats in the ensuing elections.

In August 2019, Modi unconstitutionally annulled the formal autonomy, however diluted, that Jammu and Kashmir province had been granted on its accession to the Indian Union in 1947. This, in effect, makes Pakistan a permanent enemy, with which there never again will be serious parleys about possible resolution of the Kashmir issue.

The post-Pulwama incursion was the first time since the nuclear age began in 1945 that one nuclear power in peacetime carried out conventional bombing deep in the territory of another nuclear power. Of course, the Kargil war of 1999 was the first time two nuclear powers waged war. The two countries have also engaged in major air skirmishes over the years. Further testimony is hardly required to establish the unique nuclear danger posed in South Asia.

The India-China relationship has long been fraught, beginning with efforts in 1914 by Britain, China, and Tibet to draw borders between China and then-British-controlled India. Tensions over these border lines—which India accepted but China did not—continued through the decades, eventually leading to the 1962 India-China war. After a cease fire, hostilities erupted again in 1967.

In June 2020, fatal clashes (with deaths and injuries on both sides) took place on the un-demarcated Sino-Indian border, when China advanced troops into an area hitherto left for Indian patrolling only. The last time there were border fatalities was in 1975. What provoked China? Admittedly not much provocation was perhaps needed. Under Xi Jinping, China has generally been more aggressive about its claims regarding the disputed border with India. But this is as much, if not more so, the case with the Modi government.

After coming to power in 2014, Modi fast-tracked the construction of military-related infrastructure, namely a crucial road running parallel to the Line of Actual Control that serves as the de facto border between India and China; the road was mapped in a way that would enable India to militarily threaten sections of China’s Tibet-Xinjiang highway. This project—along with New Delhi’s military turn to the United States and the Quad alliance—would have been disturbing enough for Beijing. Matters were made worse when senior officials in the BJP-RSS[2], though not in government, called for stronger ties with Taiwan and revision of India’s official acceptance of the One China policy, which calls for eventual unification of the island with mainland China. Clearly, China’s 2020 incursion, unjustified though it may be, was meant to teach India a lesson, and the overall outcome is the hardening of mutual relations.

What now?

The priority given to crude realpolitik interpretations of the “national interest” by the ruling elites in the United States, China, Russia, India, Pakistan, and elsewhere means that the world remains far away from developing the levels of international cooperation between major powers that is required to adequately address the two great evils that now threaten in large part or whole the very existence of the human species. These are the prospect of severe ecological devastation not least by climate change, and the threat of a nuclear holocaust globally since even a small nuclear exchange, say in South Asia, will result in a much wider nuclear winter. At least in respect of the latter, some possible steps to promote greater nuclear restraint and a stronger momentum for disarmament are not just within the realm of possibility but definitely feasible, even given the existing relationship of forces between and within the nuclear weapons states, and between and among the four nuclear powers facing off in South and Southeast Asia.

So I end this essay by proposing a few such measures, keeping in mind the situation in South Asian, where the India-Pakistan nuclear rivalry means both countries are pursuing triadic deployment and expanding arsenals:

- Domestic and external pressure must be put on the Biden government to ratify the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty. Once this takes place, it is virtually guaranteed that the nuclear hold-outs China and Israel (along with non-nuclear Iran) will ratify the treaty. There is every likelihood that India followed by Pakistan will then sign and ratify it.

- China and India are the two nuclear weapons states that have an official no first use doctrine. They should see the diplomatic value of a joint declaration calling on the other nuclear weapons states to adopt a similar policy and its associated negative security assurances to non-nuclear weapons states. Mutual hostilities may make this difficult to do, so a better option may be for one of the more active non-nuclear weapons countries to hold an international conference to bring about a multilateral no-first-use pledge by all those invited to attend—mostly non-nuclear weapons states but also representatives from China and India.

- The time has surely come for the establishment of an international plutonium/uranium register that relies purely on the official declarations of concerned governments and carries no intrusive verification process. Even if some of the nuclear weapons states go along with this, hold-outs—whether they do or don’t have nuclear weapons—would be diplomatically embarrassed and to that extent pressured to accept this transparency-promoting measure.

- In South Asia, one way to bring about greater public pressure on India and Pakistan is to look at the government of Bangladesh. Bangladesh is fully aware that a nuclear exchange between the two will extend grave radioactive damage to its own territory and peoples. Unlike Nepal and Sri Lanka—whose governments have not condemned this nuclearization of the region, Bangladesh has publicly done so. It is the one country in South Asia that has both signed and ratified the Treaty for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW). It has publicly called for the establishment of a South Asian nuclear weapons free zone (NWFZ). In 2011, a Member of Parliament of the ruling party, the Awami League, actually tabled a bill calling for the country to become like Mongolia, a single-state NWFZ. If assured of enough international support from other governments and progressive agencies in international civil society, Bangladesh could consider two options. One is to negotiate to join the Southeast Asian NWFZ or the Bangkok Treaty. (The precedent for this is the extension of the Treaty of Tlatelolco to the Caribbean countries.) Or Bangladesh on its own can go the single state NWFZ route. Either course would be a needed political slap in the face to India and Pakistan; would enjoy domestic popular support; and would get approval from other nuclear weapons states as well as from progressive agencies and the public most everywhere. It would also set an example for Nepal to consider following. At the very least this is an initiative seriously worth trying.

There is much to do and no time to lose!

Endnotes

[1] To take only the four major external military interventions in Korea, Indochina, Iraq, and Afghanistan (there are more than a dozen others), a very conservative estimate (since the United States does not keep proper records of non-Americans killed or wounded) of civilian deaths is given in the study by the Physicians for Social Responsibility “Body Count” at psr.org/wp-content/upload/2018/05/body-count.pdf , especially page 8 regarding Vietnam (not Indochina as a whole) and page 15 for the total after 9/11 number of deaths in Iraq, Afghanistan and the drone war in Pakistan. This international edition runs up to March 2015 and covers the 2001 to 2013 period, not beyond. See also “Korean War” at history.com/topics/korea/Korean-war, which estimates that “Nearly 5 million people died. More than half of these—about 10 percent of Korea’s pre-war population—were civilians.”

[2] The Rashtriya Sevak Sangh (National Volunteer Corps) is the parent body set up in 1925 to promote the ideology of Hindutva and to eventually set up a Hindu nation and state. It is a cadre organization with an estimated membership of over five million and a huge number of affiliates. These are currently 36 in number, of which five are all-India bodies—a women’s wing; the country’s largest student body; the biggest trade union federation; a major cultural body, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad or VHP that has branches in the Indian diaspora abroad and links up to various HIndu religious leaders and sects; and finally, a young lumpenised force that engages in local forms of vigilantism up and down the country. The BJP (whose forerunner was the Jan Sangh) is the political party that the RSS decided to set up after independence in 1950. No other party or organization has a comparable scale or depth or implantation in India civil society as does the RSS and its affiliates. The name given to this collective force is the Sangh Parivar or ‘RSS Family’.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Topics: Uncategorized