Introduction: Can the United States and China co-exist in the 21st century? Will they?

By John Mecklin | March 10, 2022

Introduction: Can the United States and China co-exist in the 21st century? Will they?

By John Mecklin | March 10, 2022

We of course are under no illusions that 20 years of hostility between the People’s Republic of China and the United States of America are going to be swept away by one week of talks that we will have there. We must recognize the government of the People’s Republic of China and the government of the United States have had great differences. We will have differences in the future. But what we must do is to find a way to see that we can have differences without being enemies in war.

—Then-US President Richard Nixon, on the White House South Lawn, February 18, 1972

President Nixon’s visit to China early in 1972 was powerful and astonishing in ways that are difficult to convey to a millennial audience. Nowadays, it is convenient to think of Nixon (when he is thought of at all) merely as a symbol of corruption, the only person to have resigned the presidency. When he visited China, however, Nixon commanded the world media stage. Even though (or perhaps because) he was heading into a re-election campaign, in one startling stroke he opened relations with a longtime bogeyman of American anti-communists—Democratic and Republican alike—in a grand strategy about-face meant to distract domestic attention from the Vietnam War, off-foot the Soviet Union, and burnish the president’s reputation as a supposed master of foreign policy. In so doing, he challenged the conservative wing of his own Republican Party in a way that would be seen by some as a nearly treasonous betrayal. Should you doubt the last sentence I wrote, read this quote from conservative icon William F. Buckley Jr., circa late February 1972:

We have lost—irretrievably—any remaining sense of moral mission in the world. Mr. Nixon’s appetite for a summit conference in Peking transformed the affair from a meeting of diplomatic technicians concerned to examine and illuminate areas of common interest, into a pageant of moral togetherness at which Mr. Nixon managed to give the impression that he was consorting with Marian Anderson, Billy Graham, and Albert Schweitzer. Once he decided to come here himself, it was very nearly inevitable that this should have happened. Granted, if it had been Theodore Roosevelt, the distinctions might have been preserved. But Mr. Nixon is so much the moral enthusiast that he alchemizes the requirements of diplomacy into the coin of ethics; that is why when he toasted the bloodiest, most merciless chief of state in the world, he did so in accents most of us would reserve for Florence Nightingale.

Between Nixon’s visit 50 years ago and now, China has undergone an extraordinary economic transformation, becoming either the second-largest or largest economy in the world, depending on the metric one chooses. Along the way, Chinese relations with the United States and the rest of the world have become—to understate significantly—more complex, entwining almost all dimensions of soft, military, and economic power.

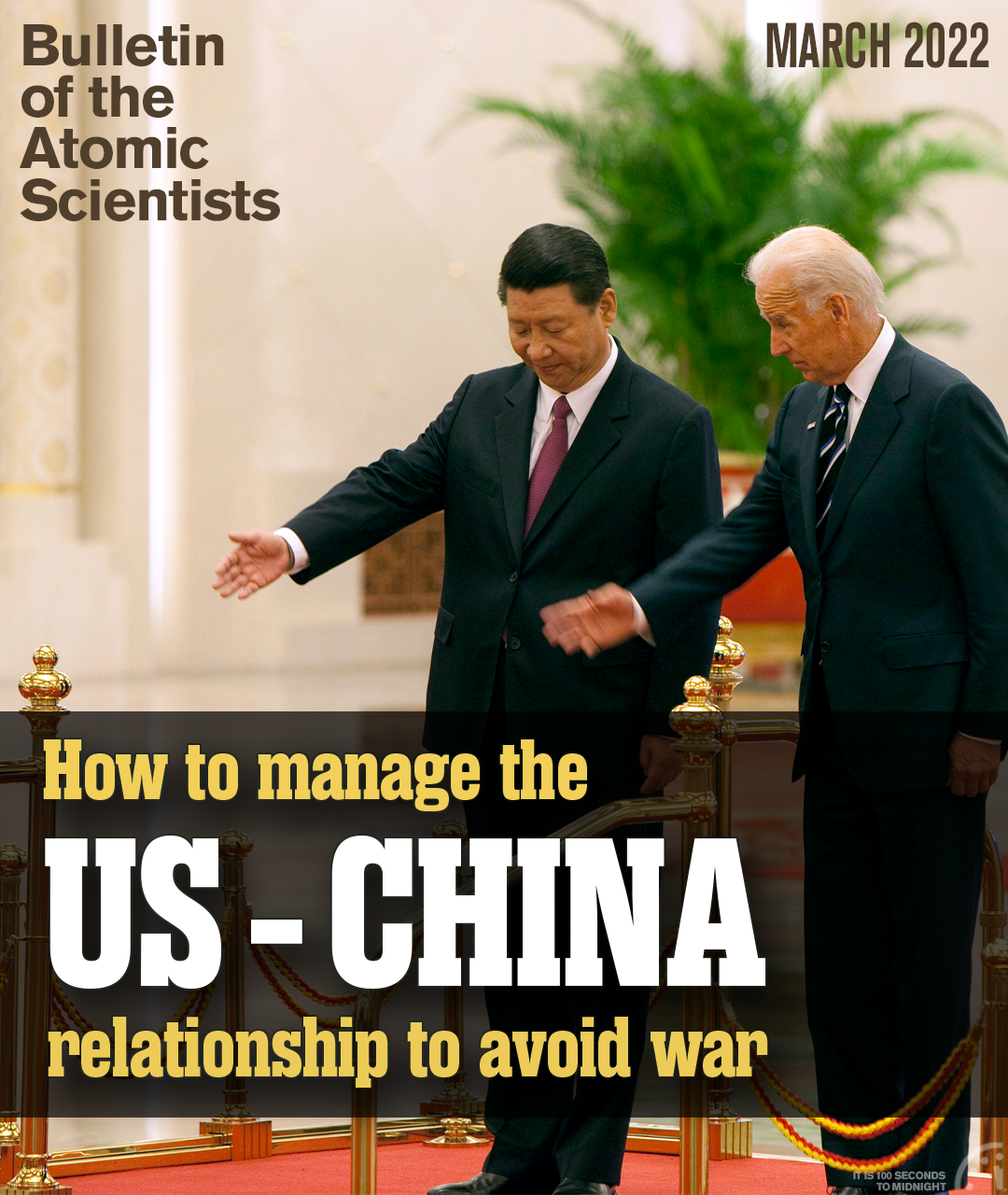

Today’s US-China competition can be seen—as acclaimed national security analyst Graham Allison explains in his interview for this issue—as a prototypical case of a rising economic and military power challenging a ruling economic and military power. Whether these two powers fall into what Allison calls “Thucydides’s trap” and go to war, à la the Athens and Sparta city-states of ancient Greece, is a drama now being played out in real time. Allison’s analysis of this complex, global rivalry and the ways it might be managed to avoid warfare constitutes a worthy starting point for discussion of the so-called US pivot to Asia.

But US-China competition can be viewed through many lenses. Another distinguished overview comes in the form of “China and the United States: It’s a Cold War, but don’t panic,” by Robert Daly, director of the Kissinger Institute on China and the United States at the Wilson Center. In his expansive essay, Daly explains why US-China relations are being framed as Cold War II, despite the current rivalry’s many differences from the original US-Soviet Cold War version. He also provides his vision for how this Second Cold War might, eventually, come to an end, and how the world might deal with its most important common challenges—climate change, pandemics, technological disruptions, and economic injustice—even as the US-China contest continues.

A major source of US-China tension of course involves Taiwan, which China views as a province that should be re-united with the mainland and which the United States and Taiwanese view quite differently. In “One if by invasion, two if by coercion: US military capacity to protect Taiwan from China,” MIT security expert Owen R. Coté, Jr. examines the two basic types of military conflict that could ensue, if China-Taiwan tensions get out of hand. In one case— in which China seeks to reunify Taiwan with the mainland via invasion—Coté sees a likelihood that the United States could frustrate the effort. On the other hand, Coté writes, should China try to use military coercion short of a full invasion to achieve the more limited aim of modifying Taiwanese behavior, the United States will find it difficult to respond effectively without crossing military thresholds that could lead to nuclear escalation. These military realities, Coté suggests, argue strongly for the United States not to make promises publicly that it will likely not be able to keep, should hostilities occur.

The US-China rivalry of course impinges on many other countries in East, Southeast, and South Asia. For this issue, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace expert Ankit Panda explains in his analysis “Sure, deter China—but manage risk with North Korea, too” why US military moves in the Asia Pacific meant to counter China could be seen as extremely threatening to North Korea —and why, therefore, the United States needs to contemplate unintended consequences, if it is to forestall a nuclear confrontation with Pyongyang. In his essay, meanwhile, South Asia security expert Achin Vanaik lays out how India and Pakistan fit into the global and regional security landscape, and how their respective relationships with the United States and China have evolved as America pivoted to Asia.

To wrap up our look at current Asia-Pacific power dynamics, US Army War College expert Lami Kim looks at the potential for competition among China, Russia, South Korea, and Japan as they attempt to satisfy the demand in Southeast Asia for nuclear power to be used in the battle against climate change. As Kim explains in understated prose, the eventual extent of nuclear power plant construction in Southeast Asia remains unclear, but “countries that make forays into the Southeast Asian nuclear market will likely wield significant influence in the region for a considerable period of time.”

As this issue of the Bulletin was being finalized, Russia had massed troops on the borders of Ukraine, raising the prospect of an invasion, even as Russian President Vladimir Putin met with Chinese leader Xi Jinping on the sidelines of the Beijing Winter Olympics. The joint statement the two leaders subsequently issued—a statement that excoriated the United States and emphasized close Chinese-Russian ties—made clear, at least, that US-China competition in the 21st century will be global and not necessarily binary in nature, and that the possibility of military conflict—thought so unlikely at the turn of this century—is real. The ensuing Russian invasion of Ukraine, accompanied by Putin’s threats to use nuclear weapons against any country that interfered, made that possibility all the more tangible.

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: China, Cold War, North Korea, Russia, Southeast Asia, Taiwan, containment, human rights, nuclear power, soft power

Topics: Opinion, Special Topics