Ten years after Fukushima: The experts examine lessons learned and forgotten

By Ali Ahmad, Aditi Verma, Francesca Giovannini | March 11, 2021

Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station. Credit: IAEA Imagebank via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 2.0.

Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station. Credit: IAEA Imagebank via Wikimedia Commons. CC BY-SA 2.0.

A decade later, the footage of the dramatic hydrogen explosions in the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, broadcast live on television—and the subsequent disruptions to livelihoods, ecosystems, and economic activities—still reverberate.

In the wake of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster in 1986, several new nuclear safety institutions such as the World Association of Nuclear Operators and the Convention on Nuclear Safety were created. Nevertheless, the West-based nuclear industry used an “us and them” pretext to mask some of the intrinsic and global flaws in nuclear safety practices, asserting that an accident like Chernobyl, caused by flawed technology and operational practices, could never happen within their own national borders. Then came Fukushima, a catastrophe that flipped such a narrative on its head and exposed the nuclear industry’s limitations in understanding the risks of the so-called “beyond design basis accidents”.

Amid a looming climate crisis and a desperate need to curb emissions, analyzing the costs, risks and benefits of nuclear energy cannot be more timely and relevant. If the global expansion of nuclear energy to address climate change is inevitable, how can we prevent, or at least mitigate, the effects of the next nuclear accident or disaster? If nuclear accidents are no longer unimaginable, can we accept the inevitability of future nuclear accidents and focus our efforts just as much on mitigation as accident prevention?

Providing coherent and credible answers to these questions in a polarized and opinionated world is not easy. Nevertheless, this is a task we took on when we organized “Nuclear Safety and Security after Chernobyl and Fukushima: Lessons learned and forgotten,” a three-day international conference hosted by the Project on Managing the Atom at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government.

This commentary series is more than just a distillate of the views that were presented during the conference by some of the world’s leading thinkers, scholars and practitioners on the 10th anniversary of Fukushima. It is a call for action, for change, and for a genuine collective engagement.

As our experts share in this series, the lessons learned and forgotten from past nuclear disasters are many. But, broadly speaking, they can be placed under four themes:

First, the impacts of nuclear accidents should not be measured quantitatively alone. Quantitative measures such as the number of fatalities or deaths per kilowatt hour are not only inappropriate, they are incomplete and unethical. The lingering human suffering resulting from forced dislocation and resettlement due to the destruction of human habitats and ecosystems ought to be fully appreciated and accounted for.

Second, there are many intangible and unquantifiable aspects of nuclear safety. These include good organizational culture (“safety culture” in the nuclear parlance), leadership, memory (so that we may remember our past failures), and imagination (so that we may anticipate the unexpected). We must look beyond hardware when we think about safety. We must consider not only technological failures but also organizational, institutional, and human failures and examine how each of them might interact with one another.

Third, it is vitally important to strike a balance between sharing information and harmonizing practices and approaches, while also developing and preserving country-specific ways of thinking about safety and security. Yet, these shared accountability mechanisms should not dilute national, organizational and individual accountability.

Finally, an aphorism bears repeating: A nuclear accident anywhere is an accident everywhere. Countries tend to assert that an accident could never happen within their own national borders because of differences in technological or institutional designs. When we embrace narratives of national exceptionalism, we lose opportunities to learn lessons from each other and set ourselves up for future catastrophe.

We hope that the commentaries presented here will inspire renewed and creative reflection on the future of nuclear safety and the governance of nuclear technologies.

Editor’s note: This collection was produced in a collaboration between the Project on Managing the Atom at Harvard Kennedy School and the Bulletin.

Chernobyl: A nuclear accident that changed the course of history. Then came Fukushima.

Better nuclear fuel could reduce the likelihood and severity of nuclear power plant accidents

Nuclear accidents will happen. What do we do about them?

Nuclear power: A question of risk and balance

Remember Fukushima: The accident is not over

A call for transnational citizen-expert engagement in nuclear compensation

What are we waiting for? The need for stronger international nuclear energy relationships.

The Fukushima accident: Do we have the wisdom to move forward?

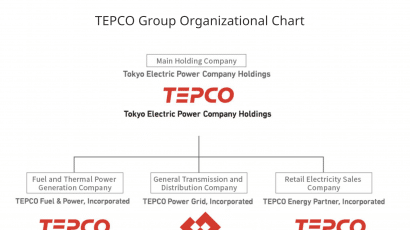

Highly enriched shareholders mean disasters down the line: Why utilities like TEPCO need new corporate governance

Asking the unasked questions

Are we ready for the unimaginable? Ensuring nuclear safety post-Fukushima

Nuclear safety and security lessons from Chernobyl and Fukushima

Together, we make the world safer.

The Bulletin elevates expert voices above the noise. But as an independent nonprofit organization, our operations depend on the support of readers like you. Help us continue to deliver quality journalism that holds leaders accountable. Your support of our work at any level is important. In return, we promise our coverage will be understandable, influential, vigilant, solution-oriented, and fair-minded. Together we can make a difference.

Keywords: Fukushima disaster, collection, introduction

Topics: Nuclear Energy, Nuclear Risk

What people and scientists seem to reject in global warming is every source of heat that is man made adds to the heat from the sun and earth. This is global warming. Heat per day from millions of barrels of oil, millions of tons of coal, btus from nuclear and YES Hydro. Electrifying is not the answer to our problem of making Earth into Mars, it is CUTTING ALL BTUS. Start by not flying or cruising, live near work, have family stay together, build earth homes with high energy efficiency. Make mining bitcoin illegal Musk will have Mars on Earth… Read more »

“If the global expansion of nuclear energy to address climate change is inevitable . . .” The global expansion of nuclear energy is closer to unimaginable than inevitable. The following facts are a matter of public record (see World Nuclear Industry Status Report 2020 at https://www.worldnuclearreport.org/-World-Nuclear-Industry-Status-Report-2020-.html and Lazard’s Levelized Cost of Energy Analysis at https://www.lazard.com/perspective/lcoe2020): Global nuclear power output has been approximately flat for decades. It is now by far the most expensive grid-scale power source and is getting costlier while wind and solar get even cheaper. New reactors take on the order of a decade to build, 5- to… Read more »